Equities A decade of QE (part 1). The impact on European equities

Since the Global Financial Crisis, the central banks of the major developed countries have pursued an extreme monetary policy. But what have been the unintended consequences?

Following on from part 1 in a series where we look at the impact that extreme monetary policy has had on European stock markets we focus now on where we go from here. Will it be more of the same old or are we likely to see some change in policy?

‘Lower for longer’ is now almost entirely consensual, which we doubt is 100% certain as inflation risk is, we believe, mispriced (see section on fiscal policy below). However, the more relevant point is that incremental cuts to interest rates from current levels is mathematically difficult. In Europe, deposit rates are -40bps. Unless the policy intention is to tax savers through charging consumers for holding cash in their bank accounts then further cuts will only hurt the banking system. As the banks are the main monetary transfer mechanism in Europe, damaging them does not seem an obvious policy goal to us. It’s not just us that doubts the sense of it. A number of ECB policy makers have publicly debated the impact negative rates are having on banks, whilst Draghi himself suggested that any further rate cuts, if required, would likely include deposit tiering to stop the banking pain. We believe it is important to underline – rates not being a constant declining force would itself be a radical change versus the past decade.

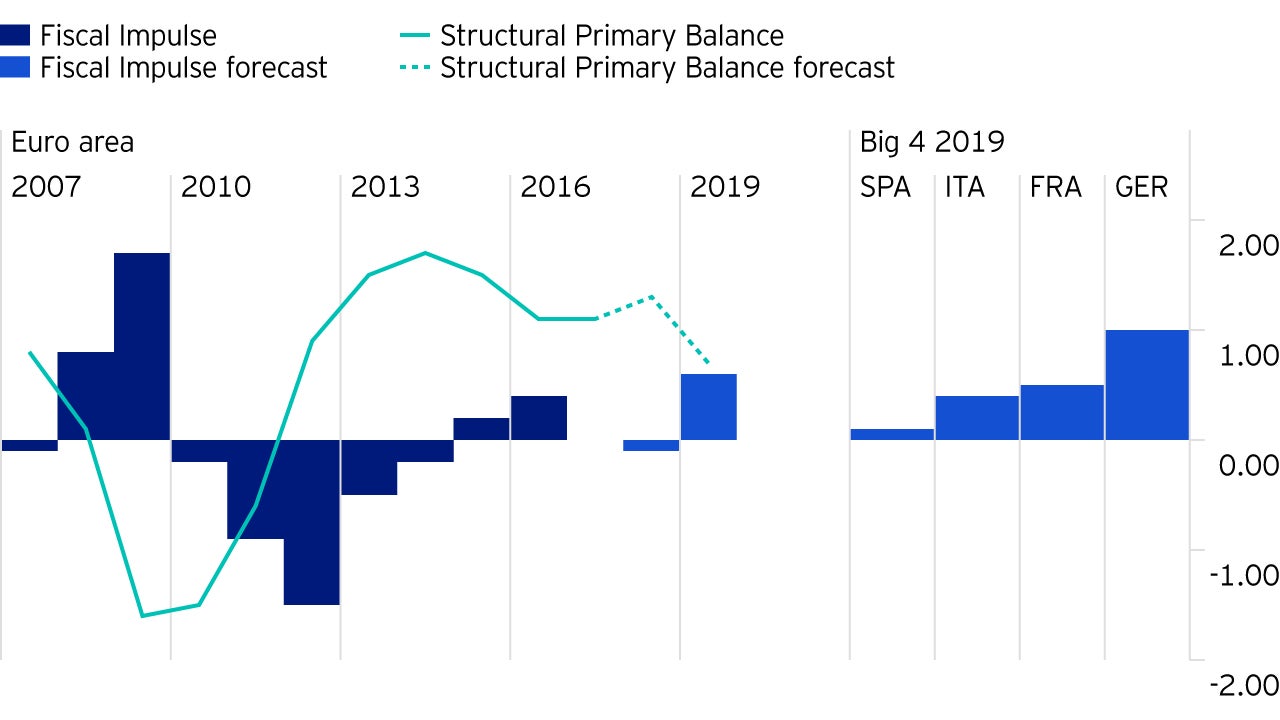

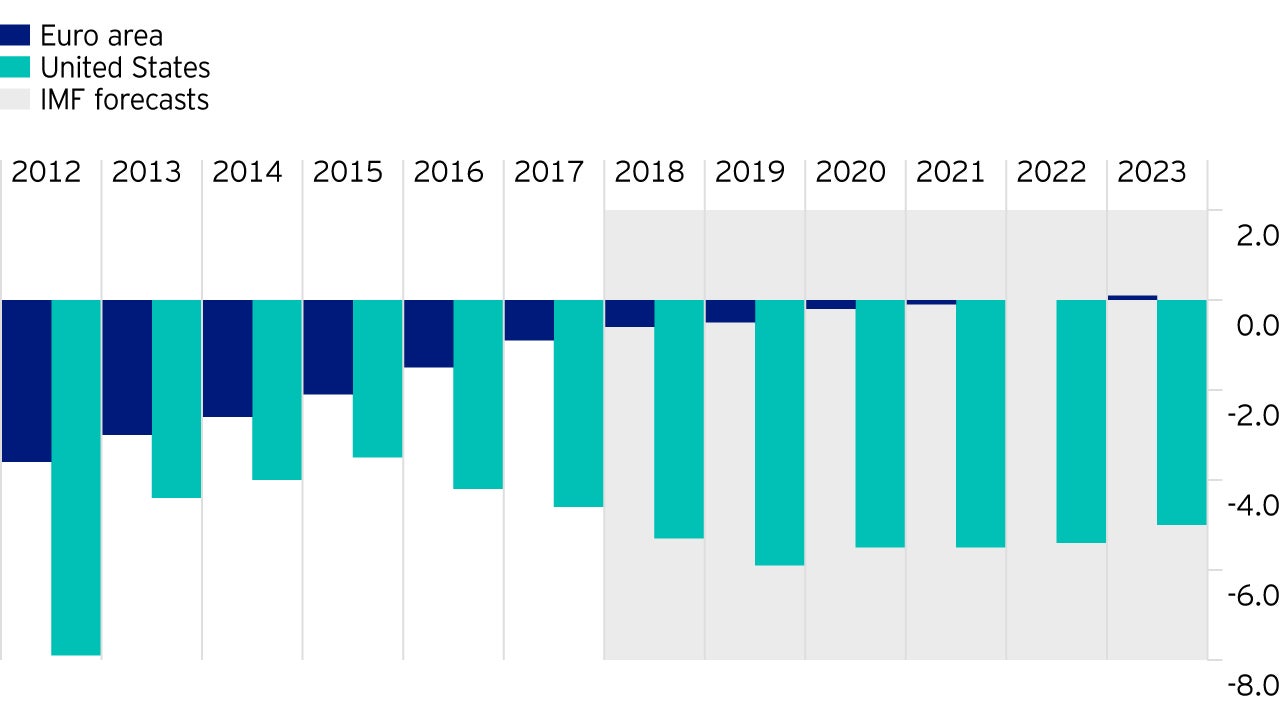

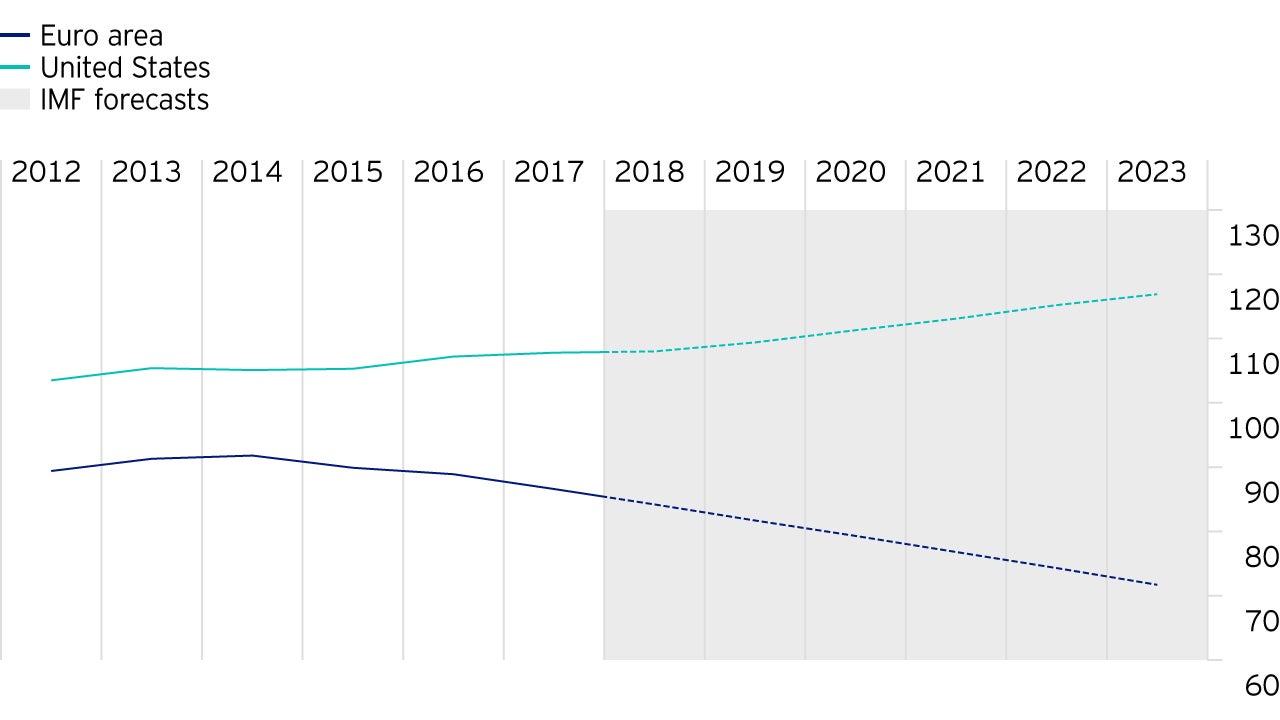

As already highlighted the policy tool-kit has relied almost entirely on monetarism. With the emphasis on reducing budget deficits, expansionary fiscal policy was regarded as impossible. Relatively recently, however, the Trump Administration has cleared that psychological hurdle. The emphasis has been on lower taxes but is starting to shift towards infrastructure. The debate now shifts elsewhere, particularly in Europe, with the core member Germany, so recently committed to a ‘black zero’ budget policy now providing the biggest delta in an uptick in Fiscal spending in 2019. President Macron, elected on a mandate of reform and budget control, has shifted with alacrity to a fiscal expansionary mode in the face of public demonstrations of anger by the ‘gilets jaunes’. The EU’s frustration with Italy’s expansionary budget was less to do with the notion of fiscal spend itself but more in the methodology of simple wealth transfer from the wealthy North to the unproductive South.

There are plenty of areas ripe for investment and the environmental agenda appears to be an increasing area of focus for potential infrastructure plans – aided by the rising political power of the Green Party in Germany (with a significant voter base within the ‘have-not’ Millennial generation). Fiscal policy is likely to be able to get inflation back into the system. As we know, prices go up when there is more demand than the available supply – so by increasing the demand for real assets and labour, the effect on inflation should be evident. Importantly, Europe in aggregate has plenty of room to flex its fiscal muscles more forcefully than it has to date.

Thus far the European moves have been tentative, but the policy debate is becoming far more widespread. The fact that rather extreme solutions such as Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) or People’s QE are being actively discussed is telling. We have no strong belief that any such action will take place, but we do think it is significant that such radical policy is being openly debated. To be fair, many mainstream economists push back against the idea rather forcefully – but equally we would note that ahead of QE the idea that the ECB would increase its balance sheet by €4.7 trillion (as of Dec 2018) through the buying of government debt and corporate bonds would have seemed fanciful in 2012.

There is increasing unease in Europe as to the damage that ever-increasing capital requirements on the banks may be having on their ability to drive the European economy forward. It is not yet clear where the debate will end, but it seems highly unlikely to us that nothing changes. In contrast, the technology sector, which has one of the lightest regulatory burdens is coming under increasing scrutiny. The impact of the ‘Gig’ economy on wages, quality of life and social cohesion is being widely discussed. All that is good in capitalism has allowed the ideas of brilliant men to thrive, but the inability of the current version of capitalism to restrict monopoly-like market positions, super-normal profitability, extreme executive pay, and societal domination is at risk of undermining confidence in capitalism itself. Pressures are beginning to mount with Commissioner Vestager taxing revenues in Europe, data regulations increasing fixed capital requirements and early stage monopoly investigations – including in the UK

The ramifications of changes in monetary, fiscal and regulatory direction are potentially significant. Crucially, the shift does not need to be violent to see those impacts become apparent. This is not about no QE, extreme MMT and regulating Big Tech out of existence. Instead, it is a recognition that the era of unchallenged monetary policy supremacy at some point requires the balance of redistribution in order to prevent malign effects. The warning shots of populism have been fired, and we sense that policy makers are beginning to recognise that fact. We do not foresee revolution, but we do predict policy evolution.

We have talked at length in the past about our investment philosophy. We do not seek to be exposed to a specific country, sector, factor or stock from an ideological point of view – our portfolio allocations are driven by a valuation framework and within that a bottom-up exploration of what drivers within the individual company can unlock that valuation gap. At present, that valuation discipline is tilting us heavily towards the Value factor, but whilst that means we are underweight Quality, it does not mean that we own ‘bad’ businesses; because the skew is so extended, we can buy excellent companies at cheap prices.

Quality in a factor sense has become narrowly defined as those businesses which have a high ROE today. We own a heavy sprinkling of cyclicals, financials, telecom and energy businesses but all are market leaders with strong balance sheets, strong cashflows and well-covered dividends. Perhaps where we differ most greatly from our peers is that our valuation discipline has increasingly taken us towards companies which are inversely correlated to the bond market – offering a natural hedge for diversified portfolios at a time where positive correlations amongst most other assets have rarely been higher.

If nothing in the policy environment changes, then the market skew may well continue but to do so requires ongoing extreme monetary policy, no regulatory change, no political reaction to income inequality, no use of fiscal policy tools and ultimately no inflation. We think this seems highly unlikely. We do not profess to know exactly what lies ahead, but we are convinced it is different to where we have come from. Equally, we feel very comfortable owning the companies that we hold.

Whilst it is not easy to predict what happens next, we believe the right answer is to hide in plain sight by owning under-valued, well-run assets and not over-valued low volatility bond-proxy equities. At current valuation extremes the optionality of policy movement looks to be wildly mispriced.