Fixed Income Managing for asymmetrical risk in EM local debt - Planning for a smoother ride

We believe the unique character of locally denominated debt in emerging markets calls for a different look at risk management and manager skill.

The trend may have peaked but we don’t think its ending.

Globalisation means many things - migration, the exchange of ideas and culture, and trade and cross-border capital flows, to name a few.

Increased trade tensions, especially between the US and China, have shined the spotlight on the topic and raised the questions, “Is the end of globalisation at hand?” and “What are the implications for investors?”

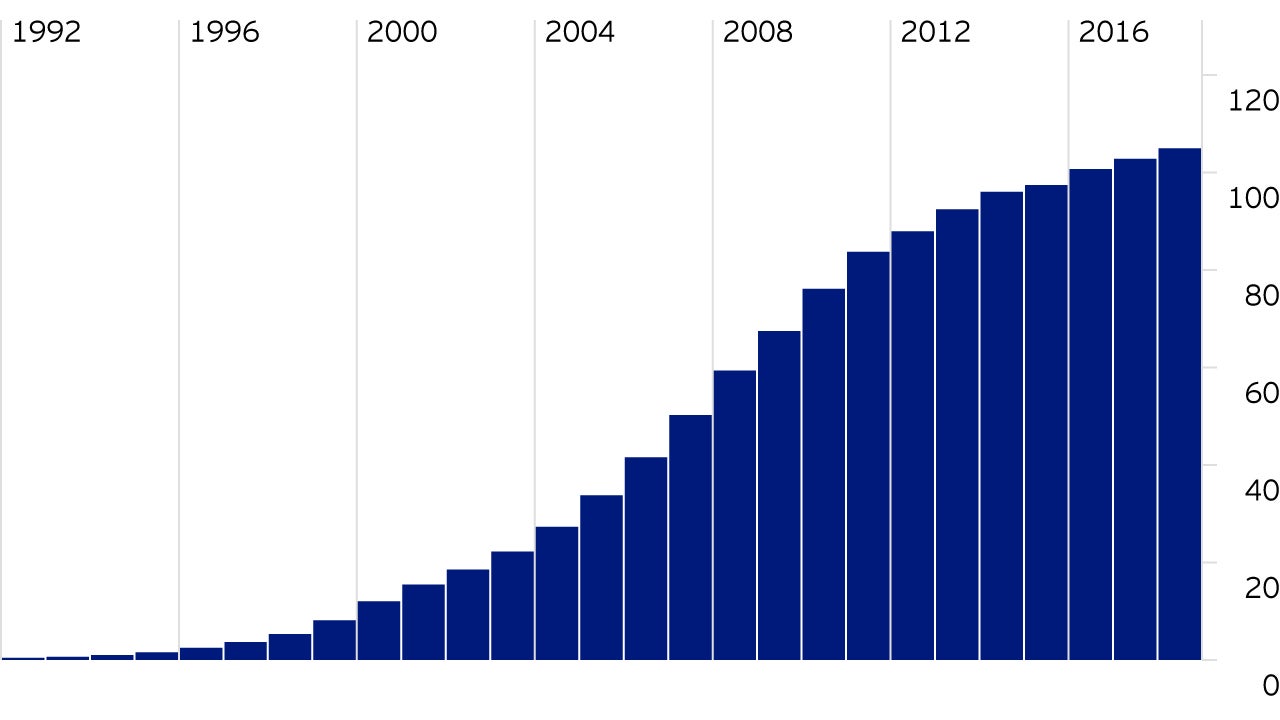

Here, we define globalisation narrowly to mean trade in goods and services and suggest that the dramatic rise in global trade flows (especially manufactured goods) witnessed over the past three decades may have reached its zenith.

We argue that this is not a new phenomenon or related only to recent trade tensions, but rather the continuation of a trend underway since the global financial crisis of 2007-2009.

We think these trends may have far reaching implications for global growth potential and especially for emerging market (EMs) economies and their existing growth models.

The globalisation and export-oriented growth models of many EMs have been credited as key contributors to rapid growth in per capita incomes in EMs, especially following China’s accession to the World Trade Organisation in 2001.

Of course, these externally based models have been accompanied by better domestic macroeconomic management too, including the deepening and opening of local financial markets, increased competition, and perhaps more importantly, an increase in foreign direct investment (FDI) that has transferred technology to EMs and improved productivity.

These developments have helped lift millions out of poverty and increased the growth potential of the world economy.

Reinforced by a dramatic decline in transportation and communications costs, the rise of global value chains (GVC) has led to the segmentation of the manufacturing process in which production is allocated to various countries based on cost minimisation.

Since 2007-2009, we have seen a discernible downward trend in FDI flows to EMs and global trade in general.

FDI to EMs has plateaued and the world is now trading less for each unit of GDP it produces than it did before the financial crisis.

We attribute this secular decline in “trade elasticity” - the sensitivity of trade to GDP - to factors such as;

We may be reaching the limits of the export-led growth models of the past century.

Historical experience suggests that, as countries grow, the goods sector’s share of the economy declines in terms of output and employment.

Once the basic needs for goods are met, consumer expenditures tend to transition to services.

Consumers may need a house, essential durables such as televisions and refrigerators, and maybe a car or two.

As these needs are met and economies develop further, consumers begin to focus on services, for example, health care, education and financial services.

We believe the answer is a qualified yes.

It is true that the world’s most successful growth models, such as South Korea and Japan, were based on exports.

While a broader market allows larger scale investment and rising incomes, we believe that productivity growth – an improvement or increase in the efficiency of work or production - is the most important factor needed to achieve long-term economic success.