The Long and Short of It - Russia’s war unleashes unique commodity shock

Overview

To rethink how the current commodity price shock might be different from most historical commodity cycles and surges.

Key takeaways

In Short

- Commodity price cycles are usually gradual, but surges are rarely across the board. Rising GDP growth and demand tend to generate gradual price rises and “super-cycles”. Supply shocks tend to cause price surges, which destroy demand, leading to supply gluts and price collapses.

- Russia’s war in Ukraine is upending global commodity markets in two unusual ways:

- An across-the-board price surge in metals, minerals, grains, energy, inputs and intermediates.

- Conflict, sanctions, and regional restrictions are restricting supply and may support prices over time.

- This unusual commodity context suggests: “high-flation” now; high costs in future; commodity market regionalization; diverse macro policies and performance on commodity importer/exporter differentiation; relative-value shifts in currencies and asset classes.

Commodity cycles and surges

Commodity prices often rise gradually when the global economy accelerates, generating sustained increases in demand. Such accelerations, occurring over years, lead to sustained commodity strength. Such “super-cycles” are demand-driven – as in the 2000s – and do not usually collapse by themselves. Instead, cyclical slowdowns usually give way to downtrends, as in the early 1990s.

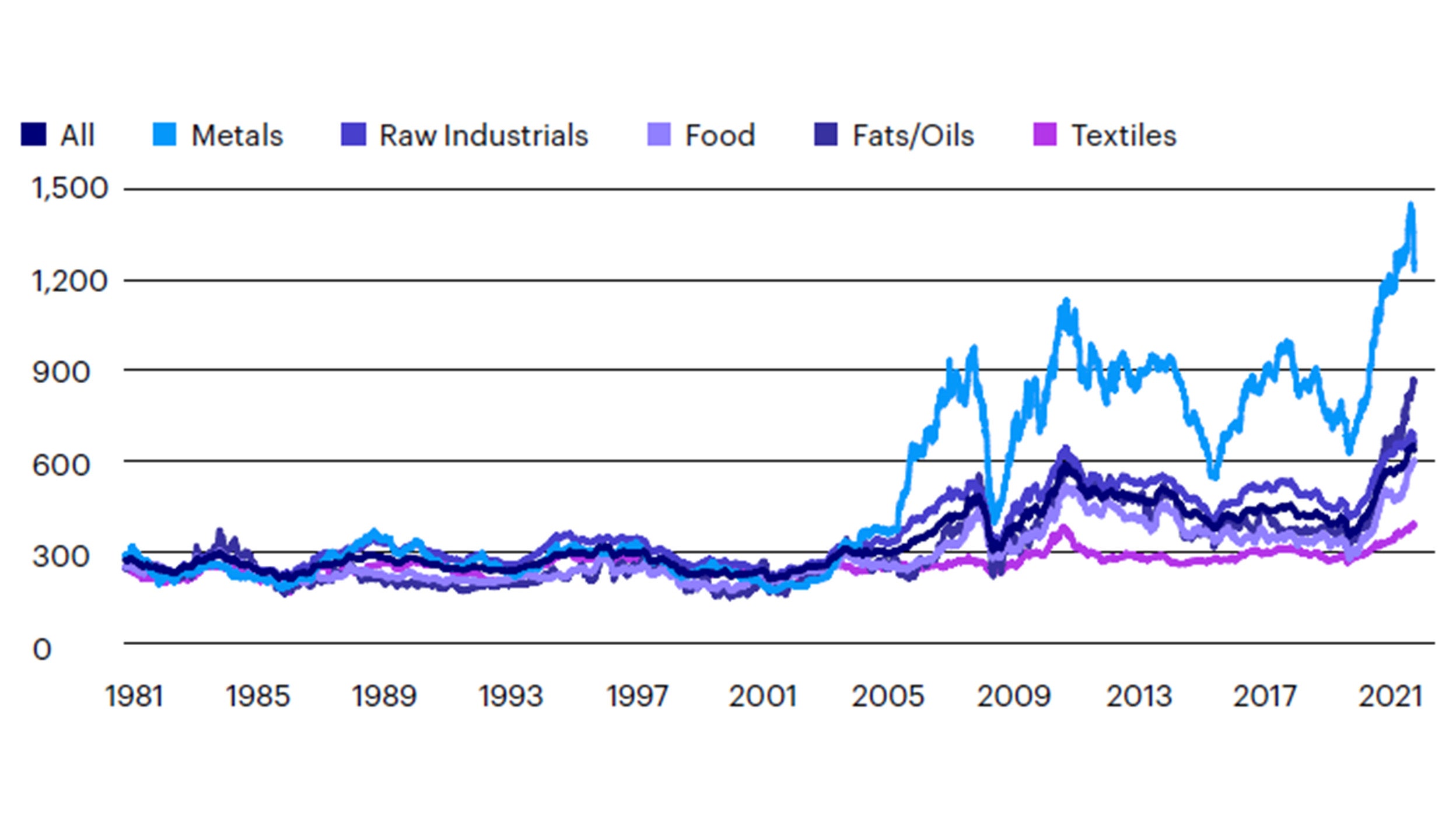

That said, severe, systemic financial crises and sharp recessions do cause price collapses, as in 2008-09; and some commodities, linked to business or infrastructure investment or transport (such as metals or energy), are usually more volatile than say softs or grains (Figure 1).

Source: CRB/Thomson Reuters, Bloomberg, Macrobond, Invesco. Data through 12 May 2022. Past performance is not a guide to future returns.

But supply-side shocks in commodities usually involve very sharp upturns, followed by severe downturns when demand destruction hits. This creates a supply glut in the commodity involved. Most supply shocks are not across the board but concentrated in one or a few commodities. They are driven by specific hits – such as a natural disaster, drought, accident, etc. This time it looks quite different.

Retaliatory sanctions for Russia’s Ukraine war point to high commodity prices for some time

Russia and Ukraine account for large global market shares in many primary commodities – energy, grains, industrial metals. The warzone also includes an outsized role in many intermediates and inputs like neon gas for semiconductors, automobile wiring harnesses, software, potash for fertilizer, as well as fertilizer itself. This much is increasingly discussed and debated, and so probably priced in.

What may lie around the corner is a more challenging commodity context for the global economy: A supply-led price shock is yielding to embargoes and potentially permanent regional restrictions. Thus, the demand destruction usually caused by commodity price surges may not be followed by the typical price collapse that helps to free up consumer spending power, eventually restoring demand.

Instead, the combination of conflict and sanctions is poised to restrict supply, geographically segmenting commodity markets for some time to come, perhaps permanently. These effects would strongly impact food, energy and industrial intermediates, and perhaps more than industrial metals:

- Energy – Regionalisation? The EU, UK and US are boycotting Russian energy, step-by-step. Russian coal is already being cut off. An EU oil boycott is in the works, following US and UK boycotts. Russia is gradually embargoing gas exports to the EU, cutting off Poland and Bulgaria and reducing flows to Germany. These restrictions may take months or years to take their full effect, and may never be comprehensive, but the decoupling of the West from Russian energy is the clear direction of travel. Russia’s oil trade already seems to be shifting to China and India, with gas pipelines in the works for China and Pakistan. Thus, the entire energy complex may become regionalized, like gas, instead of globalized as oil is today.

- Grains – Redirection? The conflict is already cutting Ukraine’s capacity to export harvested grain due to blockades, mining of coastal waters and destruction of port cities like Mariupol or attacks on Odesa. Russian forces are reportedly plundering grain stocks and destroying farm equipment. The Kremlin may try to take over Ukraine’s grain exports to emerging markets (EM), which along with sanctions may segment grain markets across regions and keep prices elevated, if Ukraine’s future harvests are restricted or redirected toward the West, and Russian grain towards EM.

- Metals – Restructuring? Russia is a major exporter of many industrial metals – aluminium, nickel, platinum, palladium. But metals as a whole is a relatively diversified global market in which Brazil, South Africa and others provide alternative sources of supply. In some metals, such as palladium, Russia commands a strong market share and will likely wield greater leverage over pricing and destination than others which are on a more level global playing field, like aluminium.

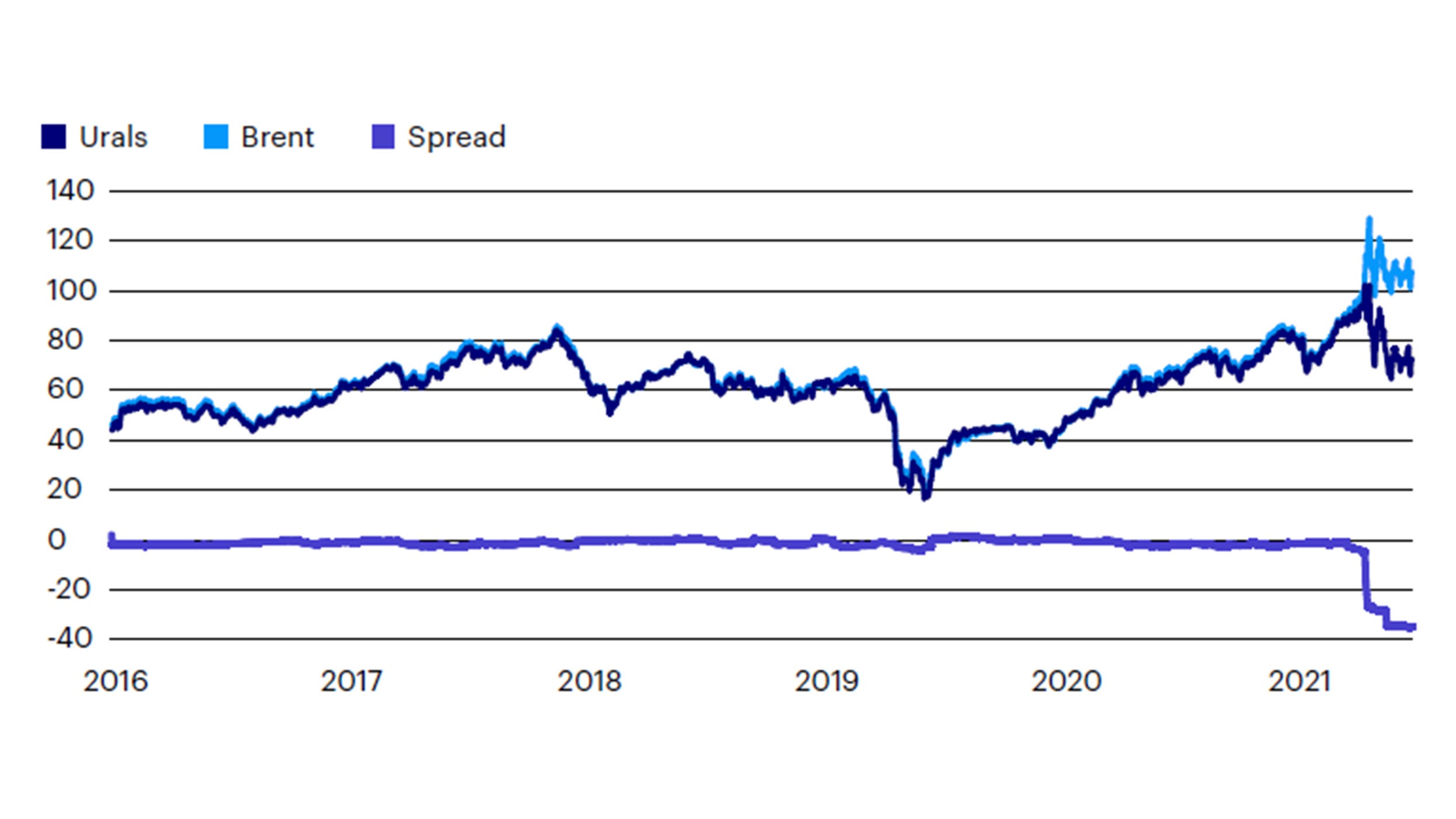

The prospect of oil market regionalisation already seems to be driving relative value in oil markets – specifically the Urals-Brent spread. Russian Urals typically traded at a small, procyclical discount to Brent – a tight price spread would narrow when oil prices rose or widen when they fell. But the Urals spread collapsed even as the Brent price skyrocketed upon the invasion, reflecting the risks of oil sanctions and restrictions (Figure 2).

Since then, both the Urals and Brent price have been very volatile, but the spread may be stabilising in the 30s. While Western governments and firms boycott Russian oil, Russia is finding other buyers, such as China and India, who are not imposing sanctions, helping to steady the Urals market. This sharp, countercyclical collapse in the Urals-Brent spread itself suggests regionalisation, and its stabilisation may well mark the start of an era of geographically differentiated pricing.

Source: CRB/Thomson Reuters, Bloomberg, Macrobond, Invesco. Data through 12 May 2022. Past performance is not a guide to future returns.

Five key macro/market implications

- “High-flation” here and now: Russia’s wartime commodity inflation price shock and subsequent retaliatory supply restrictions follow hard on the heels of Covid lockdowns and re-openings.

To recap, lockdowns unleashed a great compression in economic activity and commodities, services, goods prices and wages. Major economies provided the most fiscal/monetary support on record in any downturn. Consumers reallocated spending from services to goods, propelled by pent-up savings and fiscal transfers. Lockdownrelated supply-chain challenges caused a strong updraft in goods prices, relative to services. On reopening, upward pressures have begun spreading to services prices and wages per the most recent data, especially in the US and UK.

Now, the Russia-Ukraine commodity shock is already boosting inflation. These effects are most pronounced in the West and many EM but least pronounced in Japan, China, where Covid zero-tolerance lockdowns are holding back commodity prices and global demand.

- Higher costs, lower growth in future: Investors need to factor in the very real possibility that commodity prices remain higher than they would otherwise be, after this supply shock. Instead of falling back sharply on demand destruction and supply gluts as normally happens, energy and food prices may well remain high for an extended period, restricting consumer spending on discretionary purchases, especially for lower-income earners in most countries, as well as in EM.

Inflation might slow considerably, as commodity price increases slow, stop or even reverse with demand destruction, but the costs of production and basic needs might end up sustainably plateauing at a high level. This in turn would imply lower trend growth for commodity importing countries. The silver lining is that higher prices should encourage climate-friendly innovation and substitution of renewables and more efficient use of existing resources.

- Commodity market regionalization: Many commodity markets have been globalized until now. But the West is already putting into practice its plans to decouple from Russia’s energy exports. Russia’s interest in reducing its dependence on European export markets and redirecting exports towards Asia points to sustained, perhaps even permanent commodity regionalization.

Signifying a structural break with the past, Germany has ditched “Ostpolitik” – the policy framework of diplomatic and economic engagement with the “East” – the USSR then Russia – for most of the post-WWII era until the invasion. Russian President Vladimir Putin has sometimes mentioned “security of demand” for Russia’s exports during his two decades in power in rebutting security of supply concerns mooted by the US. Now, both Russia and the West see national security as threatened by interdependence and enhanced by decoupling.

- Segmentation more than de-globalization/fragmentation: It is all too easy to jump to the conclusion that deglobalization is unfolding before our eyes, based on national security and existential risks posed by Russia’s war in Ukraine, as well as concerns about sovereignty in Asia. However, complete global economic fragmentation is far from inevitable – or even likely – for various reasons. Trade links remain open and investment flows are almost certain to persist.

First, though commodity market regionalization implies price differentiation across regions, there are limits to how far such differences can go. At some point, at some price difference, trade arbitrage will become too attractive to ignore, even at the risk of secondary sanctions.

Second and as important, great-power rivalry between a “Western democratic alliance” and an “axis of autocracy” is likely to extend to a struggle for geopolitical and economic influence in EM that are not fully aligned with any world power. Instead of Cold-War type proxy wars, we expect ongoing trade and investment in many EM by all major economies of all political stripes.

Last, but not least, many major EM also see themselves as great powers and civilisations in their own right and will continue to try to grow and innovate. To achieve their own ends, a degree of openness to ideas, technologies and by extension trade and investment with the West.

One important player on this front is India, which has reasons to maintain links with both the West and with Russia – not least as a counterweight to China. Some other major EM – notably Brazil and South Africa – gain directly from higher prices for their own commodity exports, as well as the possibility of exporting to both the axis of autocracy and the democratic alliance. All are roughly neutral between the West and Russia. Collectively and in some cases as individual economies and regional powers, EM are too important for the West, China or Russia to ignore.

- Cyclical and structural diversity in monetary policy and macro/financial performance: There was a time that the world economy largely experienced a single, global cycle, with most economies slotting into a natural place reflecting the structure of their international trade, investment and economic activity, driven by increasing openness to cross-border flows of commodities, goods, investment and financing.

Back then, cyclical asset allocation could be driven mainly by the current position of the world economy in the global cycle, since risk assets like equities and EM, would do well as growth accelerated; or perceived risk-free bonds and the dollar would do well as growth and inflation slowed. When growth was decent but inflation too low, or when both growth and inflation were too low, central banks would cut rates as far as possible and then buy bonds driving down yields, pushing investors to reach for return in longer duration and higher risk assets.

This previously hyper-globalized world economy is now giving way to segmented markets in goods and services trade (see for example, Brexit); financial and corporate investment (based on national security or regulation); migration (Brexit again, or EU and US restrictions); supply-chain realignments and near-shoring (Covid); and now commodity market regionalization. All of the above are affected to some degree by geopolitics and yet are also likely to work within limits.

These factors all will play out differently in different economies, reflecting the composition of their trade and competitive advantages as sources for trade and as investment destinations. The global economy is thus transitioning from a global cycle in which each major economy had a natural place, to the sum of individual national cycles. Different economies would have quite different trend growth rates, productivity levels and national per capita incomes (given limits to trade, investment, technology transfer and migration, which had previously driven convergence).

What does this mean?

In sum, some countries and associated asset classes are likely to do better than others, as economic potential would be more driven by national policies and constrained by natural resource endowments and demographics than global market forces. Country selection and diversification should therefore gain emphasis in asset allocation decisions – possibly even taking pride of place from asset allocation based on the current position of the global economic cycle.

At present, we would expect this diversity to continue to show up in a hawkish US Federal Reserve, neutral European Central Bank (ECB) and Bank of England (BoE), and dovish People’s Bank of China and Band of Japan (BoJ), with a wide mix across EM central banks –though with most remaining in restrictive territory.

This continuing realignment in monetary policy, following the widespread convergence of easy monetary policies during Covid lockdowns, points to greater differentiation among currencies, based on a combination of commodity effects and central banks. Dollar strength already reflects this, along with a relatively strong Brazilian real for example. But limits to the ECB and BoE tightening, given Russia/energy-related growth challenges, and continued BoJ easing suggest continued weakness against the dollar.

A stronger dollar, higher Fed rates and a higher US yield curve also points to tighter financial conditions and a challenge for US growth and tech shares, while a higher commodity price environment and weak sterling continue to bode well for the UK equity market (though not for domestic facing UK stocks), relative to the US or EU indices.