Uncommon truths Global debt review 2022

Global debt ratios declined in 2021 on the back of the rebound in GDP. Falling bond yields dampened the rise in debt service ratios over recent years but that is now changing. We fear the corporate debt burden could become a problem in some countries.

The man from Mars may question whether planet Earth has a debt problem (if so, to whom is it owed?). However, the global financial crisis (GFC) showed that, even if net debt is zero, it is difficult to unwind that debt when there are so many interlinkages. We therefore assume that more debt brings more risk. Hence, our annual review of global debt. Now that the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) has published its 2021 data, we are able to deliver the next instalment.

After a record jump in global debt-to-GDP ratios in 2020, relief came in 2021 with the reversal of around a half of the 2020 gain (depending on how it is measured). The sharp jump in debt-to-GDP in 2020 was the result of a combination of rising debt (especially in the public sector) and falling GDP (both of which were due to the effects of the Covid pandemic). However, the decline in the debt ratio in 2021 was entirely due to the jump in GDP, as debt continued to rise.

The global debt-to-GDP ratio fell from 257.7% in 2020 to 248.9% in 2021 (based on the BIS “All-Country” non-financial sector debt-to-GDP ratio, using purchasing power parity (PPP) exchange rates to convert all data to US dollars). Though welcome, this decline still leaves the debt-to-GDP ratio above the pre-pandemic level of 227.4%, as reported in 2019.

We believe that using PPP exchange rates is the best way to calculate such aggregates, since the use of market exchange rates causes too much volatility in the global series. For example, using market exchange rates, the BIS All-Country aggregate debt-to-GDP ratio would have fallen even more (from 290.8% in 2020 to 264.4% in 2021), having risen by nearly 45-percentage points in 2020.

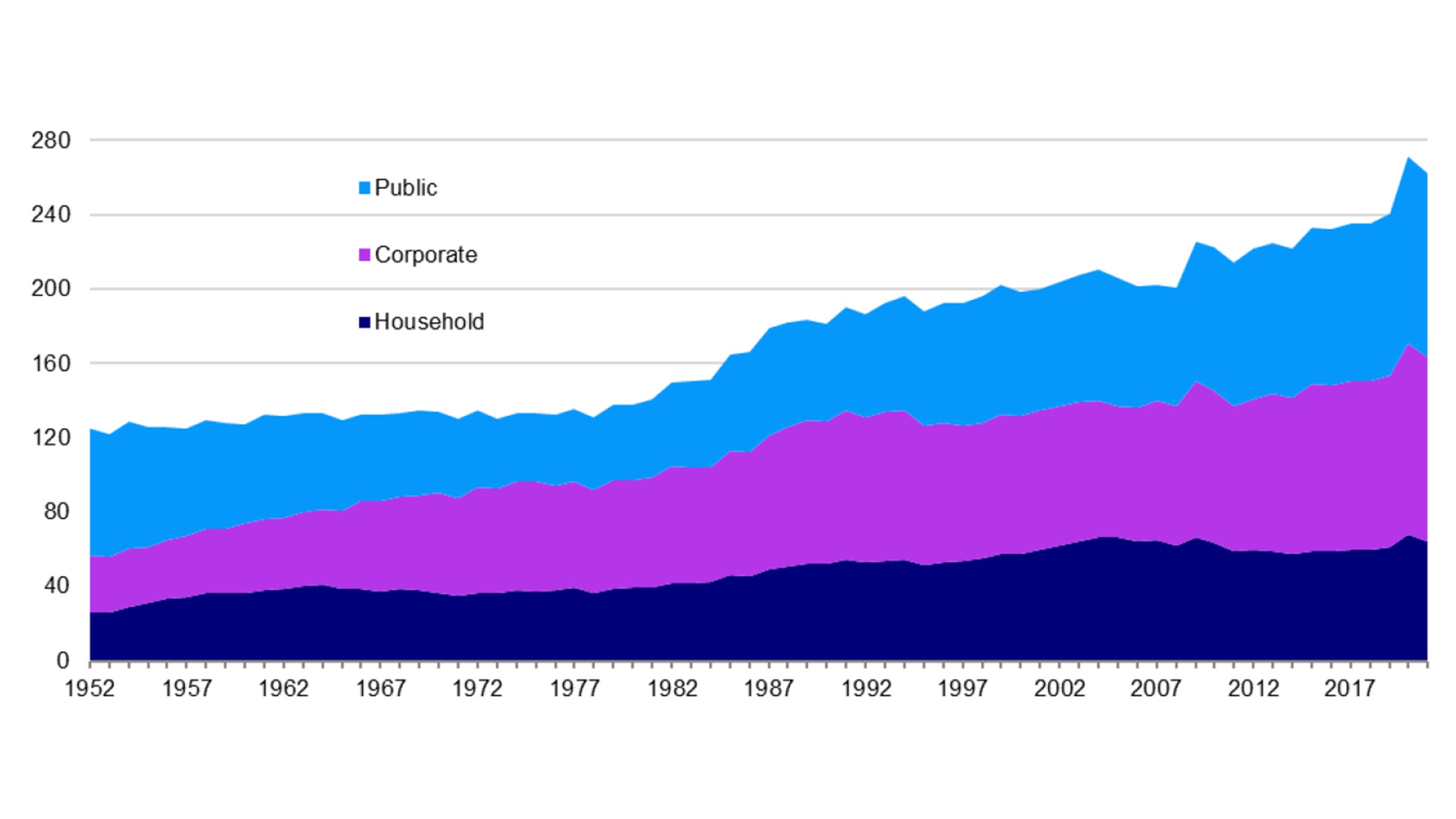

The problem with BIS All-Country aggregates is that they only go back to 2001, so we have constructed our own version by aggregating the data for the world’s 25 largest economies (as of 2019, measured by GDP). Figure 1 shows the results and suggests that, after reaching a new high of 271.1% in 2020, the global debt-to-GDP ratio fell back to 262.4% in 2021 (it was 240.2% in 2019). Unfortunately, our measure is based upon market exchange rates, so we use a smoothing process to dampen the effect of exchange rate movements (see the note to Figure 1).

Casual inspection of Figure 1 suggests that global debt-to-GDP declined in all three sectors (households, corporates and governments), though the dollar amount of debt increased in all categories.

Note: Based on annual data for the 25 largest economies in the world (as of 2019). Data was not available for all 25 countries over the full period considered. Starting with only the US in 1952, the data set was based on a successively larger number of countries until in 2008 all 25 were included in all categories. The data for all countries is converted into US dollars using market exchange rates. Unfortunately, debt is a stock measured at the end of each calendar year, whereas GDP is a flow measured during the year so that when the dollar trends in one direction it can distort the comparison between debt and GDP. To minimise this problem, we use a smoothed measure of debt which takes the average over two years (for example, debt for 2021 is the average of debt at end-2020 and at end-2021).

Source: BIS, IMF, OECD, Oxford Economics, Refinitiv Datastream and Invesco

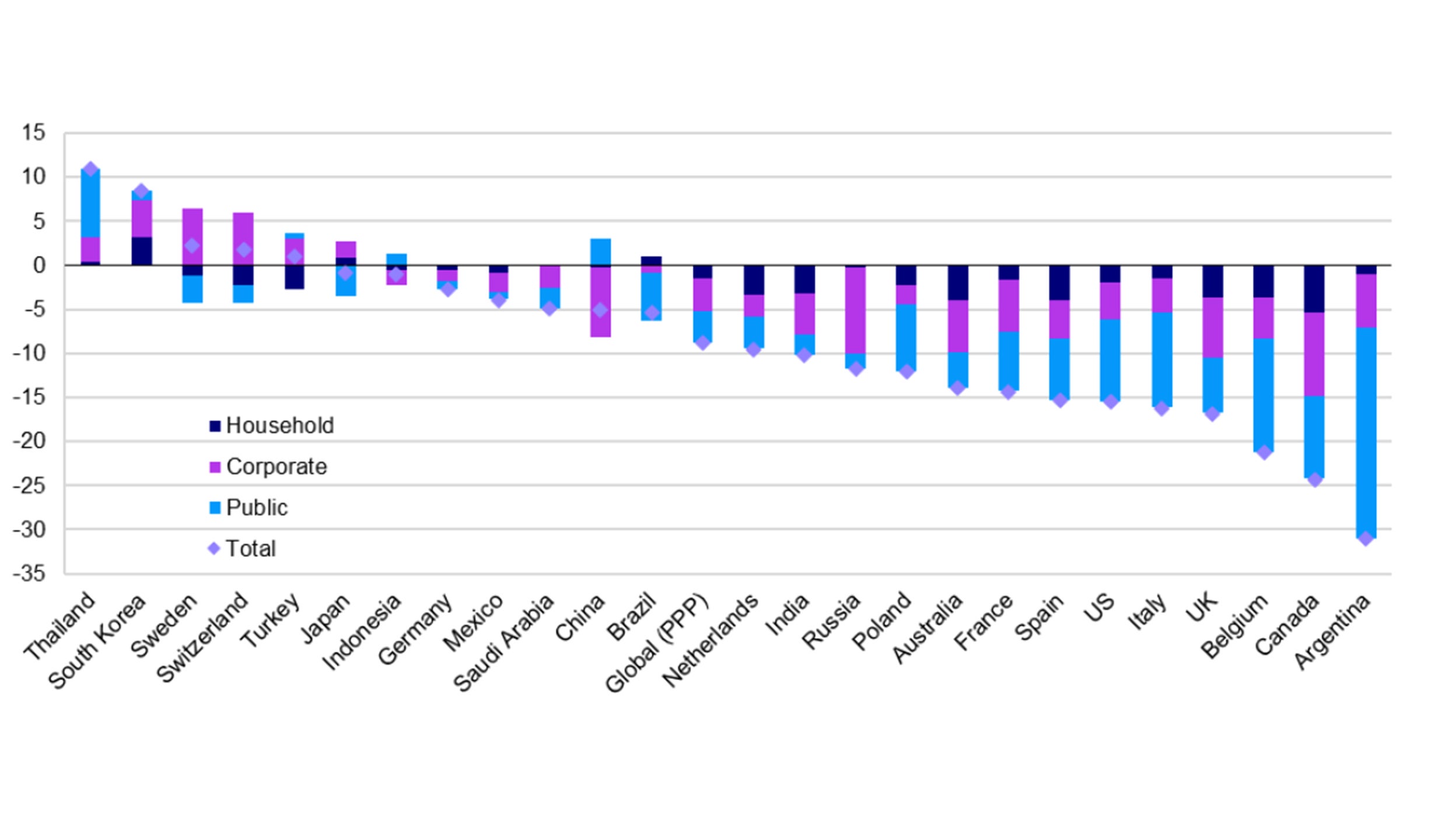

Figure 2 shows the detail of last year’s fall in debt by country and sector (in terms of changes to debt-to-GDP ratios). Total debt ratios declined in 20 of the 25 countries that we follow, with the biggest reductions in Argentina, Canada and Belgium. Among those three, the only one to see a decline in the dollar amount of debt was Belgium (due to a decline in both public and private sector debt). At the other end of the spectrum, Thailand and South Korea had the largest jump in debt ratios, with the rise in private and public sector debt sufficiently large to outweigh the rise in GDP.

Belgium was not alone in seeing a decline in debt when measured in US dollars but this was always due to exchange rate movements (strengthening dollar), with total debt rising in all 25 countries when expressed in local currency. In fact, Denmark was the only country in the BIS universe that experienced a decline in total debt in local currency.

Looking to longer term trends, total debt ratios have risen substantially in the last 10 years. The global debt-to-GDP ratio increased by 46 percentage points in the 10 years to 2021 (whether using market or PPP exchange rates), with 18-21 percentage points of that coming since 2019 (depending on which exchange rates are used). The 10-year change is largely due to the rise in corporate and public sector debt.

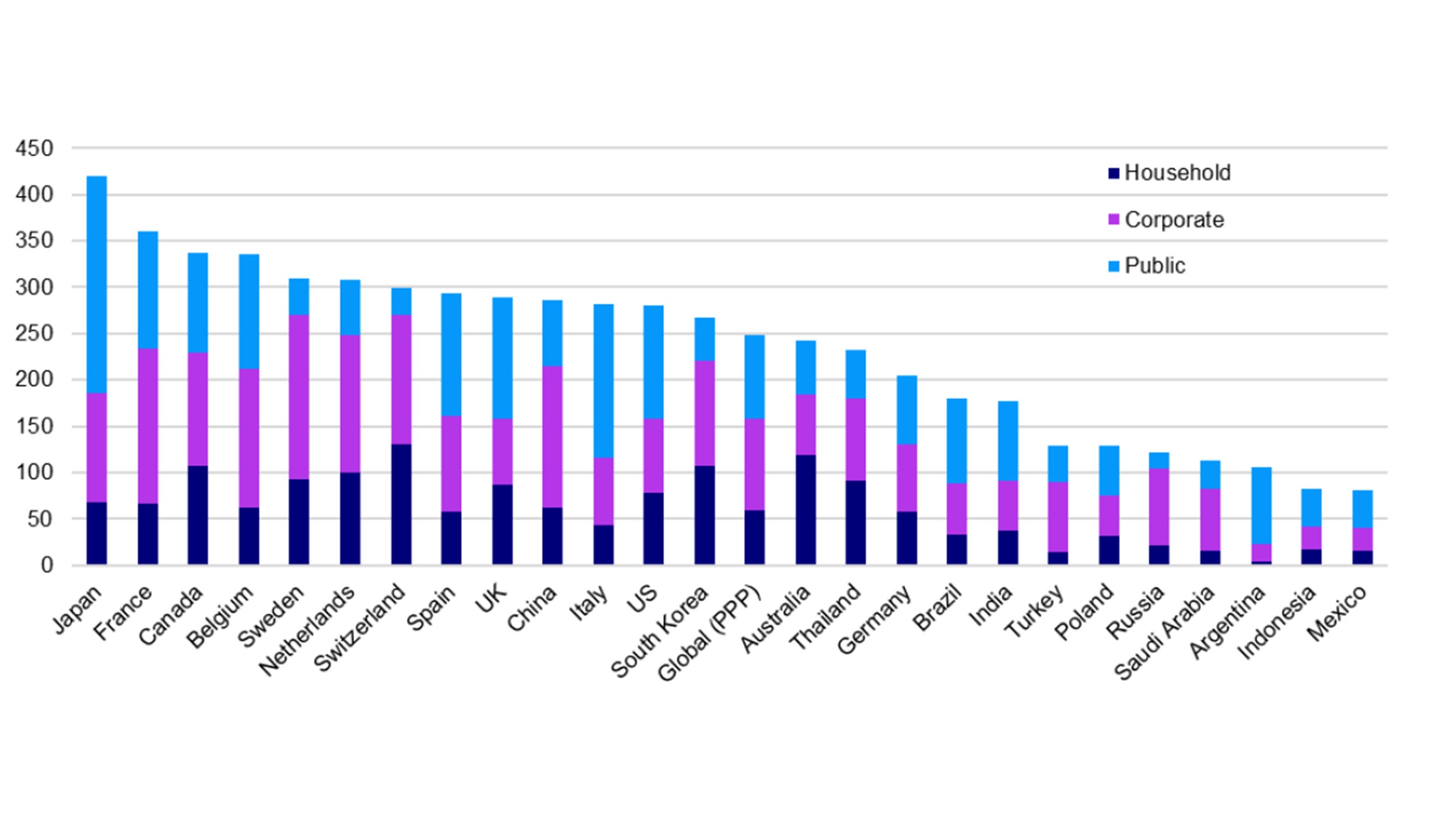

Only four countries experienced a decline in their total debt-to-GDP ratio over the last 10 years: the Netherlands (-37.5 percentage points), Germany (-3.5), Poland (-3.5) and India (-3.1). Though the Dutch debt-to-GDP ratio declined in all three sectors, the decline in the corporate sector debt ratio was the most impressive, followed by the household sector.

China is the country with the largest rise in the debt-to-GDP ratio over the last 10 years, with a 108 percentage point increase (from 178.4% to 286.6%), with roughly equivalent gains in the debt ratios of households, corporates and the government. Next in line is France (+88 ppts over 10 years) and Canada (+73 ppts). France is the country with the largest three year increase (+45 ppts), with the corporate and public sectors accounting for most of the rise in debt.

So where does this leave accumulated debt across countries? Figure 3 shows debt-to-GDP ratios for the 25 countries that we follow. As has been the case for some time, the countries with the biggest debt burdens are to be found in the developed world, with Japan once again leading the way, though its debt-to-GDP ratio edged down from 420.8% in 2020 to 419.9% in 2021, according to BIS data. The next three countries (France, Canada and Belgium) are the same as last year. The first change in ranking occurs at #5, with Sweden moving up from #7 and replacing the Netherlands, which falls to #6.

Other countries on the move in 2021 in Figure 3 include: Switzerland (from 10th to 7th), Spain (6th to 8th), UK (8th to 9th), China (12th to 10th), Italy (9th to 11th), US (11th to 12th), Brazil (18th to 17th), India (17th to 18th), Turkey (22nd to 19th), Poland (19th to 20th), Saudi Arabia (23rd to 22nd), Argentina (20th to 23rd), Indonesia (25th to 24th) and Mexico (24th to 25th).

Note: Based on year-end local currency non-financial sector debt-to-GDP ratios. “Global (PPP)” uses BIS “All reporting countries” data, using PPP exchange rates (it is based on a larger sample of countries than is shown in the chart). The change is calculated as the end-2021 debt to GDP ratios minus those of end-2020. The countries shown are the 25 largest in the world by GDP, as of 2019.

Source: BIS, Refinitiv Datastream, and Invesco

So, after a sharp rise in debt ratios in 2020, there was a decline in 2021 due almost entirely to the recovery in GDP, with debt continuing to rise in almost all cases (not unusual in the early stages of economic recovery). Normally, we would expect a further decline in debt ratios as economies continue to expand and debt levels decline as public sector expenditure declines and public and private revenues increase. However, this time appears to be different, with the inflation and cost of living crises likely to require more government expenditure, while imposing an income shock on the private sector.

That may push debt levels up but higher inflation could boost nominal GDP growth, thus depressing debt ratios, even if real GDP growth slips (perhaps into recession). However, we doubt that is a recipe for driving debt ratios lower over the medium term.

Of course, debt only becomes a problem when debt service ratios increase. The rise in debt-to-GDP ratios over the last 10 years was not as big a problem as it might have been because bond yields fell to historical lows in the developed world. However, the sharp rise in bond yields during 2022 may change the picture.

Governments have the luxury of being able to use the tax system to increase income if debt service ratios increase. The private sector has no such ability (raising prices may damage sales), so it is perhaps more important to focus on the affordability of private sector debt. Comparing BIS derived private sector debt service ratios (interest payments plus amortisations divided by income) at the end of 2019 and the end of 2021 gives a mixed picture. There were notable declines in Australia (from 19.4% to 17.3%), Canada (24.4% to 22.7%), India (11.2% to 9.7%), Netherlands (25.6% to 23.8%), South Africa (8.9% to 7.0%) and the US (14.5% to 13.4%). Some of those countries may have benefitted from the rise in commodity prices that started in mid-2020.

However, there were also some notable increases in private sector debt service ratios between end-2019 and end-2021, with the biggest in Turkey (13.7% to 19.7%), Brazil (18.1% to 21.3%), Sweden (23.7% to 26.6%) and France (19.4% to 20.8%). In all cases where data is available, the major contributor to the rise in debt service ratios was the corporate sector, with notable gains in Sweden (+8.9 percentage points to 56.0%), Spain (+7.3 ppt to 39.4%), Japan (+6.7 ppt to 40.0%) and France (+6.5 ppt to 61.1%).

Of course, countries such as Brazil and Turkey had already seen a big rise in bond yields in 2021 which may explain some of the rise in their debt service ratios. However, the rise in yields in much of the developed world has been concentrated in 2022 and may only just be starting to impact debt service ratios.

If corporate debt is to become a risk, we suppose the biggest threat would be in countries where service ratios are the highest. As of end-2021 this list of countries would be France (non-financial corporations debt service ratio of 61.1%), Sweden (56.0%), Canada (51.3%), Belgium (43.6%), Netherlands (43.2%), South Korea (40.7%) and the US (40.1%). For the most part, those are the countries in which corporate sector debt is the most elevated.

Unless stated otherwise, all data as of 08 July 2022.

Note: “Global” uses BIS “All reporting countries” data and is calculated using PPP exchange rates (it is based on a larger sample of countries than is shown in the chart). The countries shown were the 25 largest in the world by GDP, as of 2019.

Source: BIS, Refinitiv Datastream and Invesco