Uncommon truths: Why I like Chinese equities

Chinese equities have recently outperformed other regions (while bonds have done the reverse). We ask whether this is a dead-cat bounce or the start of a new trend. There are many worries about Chinese stocks but we suspect a lot of that is already in the price, based on cyclically-adjusted valuations. We are happy to be Overweight within our Model Asset Allocation.

Having just spent a week in the Middle East, I was struck by the vibrancy of the region (and the heat and sandstorms!). There may be more Covid precautions than in Europe but life is going on as usual. One sign of a booming economy is high load factors on flights and seats are hard to come by within the region. Apart from anything else, I guess this is a sign of the benefits of being endowed with energy resources when oil and gas prices are rising.

In discussions with investors, I encountered far more interest in cryptocurrencies than I have seen in Europe. It would appear that recent turmoil has done little to dampen the appetite for such instruments, especially among the younger generation. This confirms what I have heard in recent discussions with non-investor acquaintances in the UK, who are looking for the next buying opportunity, despite recently locking in losses of up to 60%. This makes me think that the revulsion stage is yet to be reached and that a lot more downside will be needed before a true bottom is formed (Bitcoin may need to go below $10,000 for that to happen, in my opinion).

There was obviously a lot of concern about inflation, recession risk and central bank policies and I had the feeling that my views were among the most aggressive in terms of how quickly headline inflation would decline over the next 12 months (see The causes and course of inflation). There was also a lot of interest in China for several reasons including geopolitical risk, short-term economic concerns and investment opportunities.

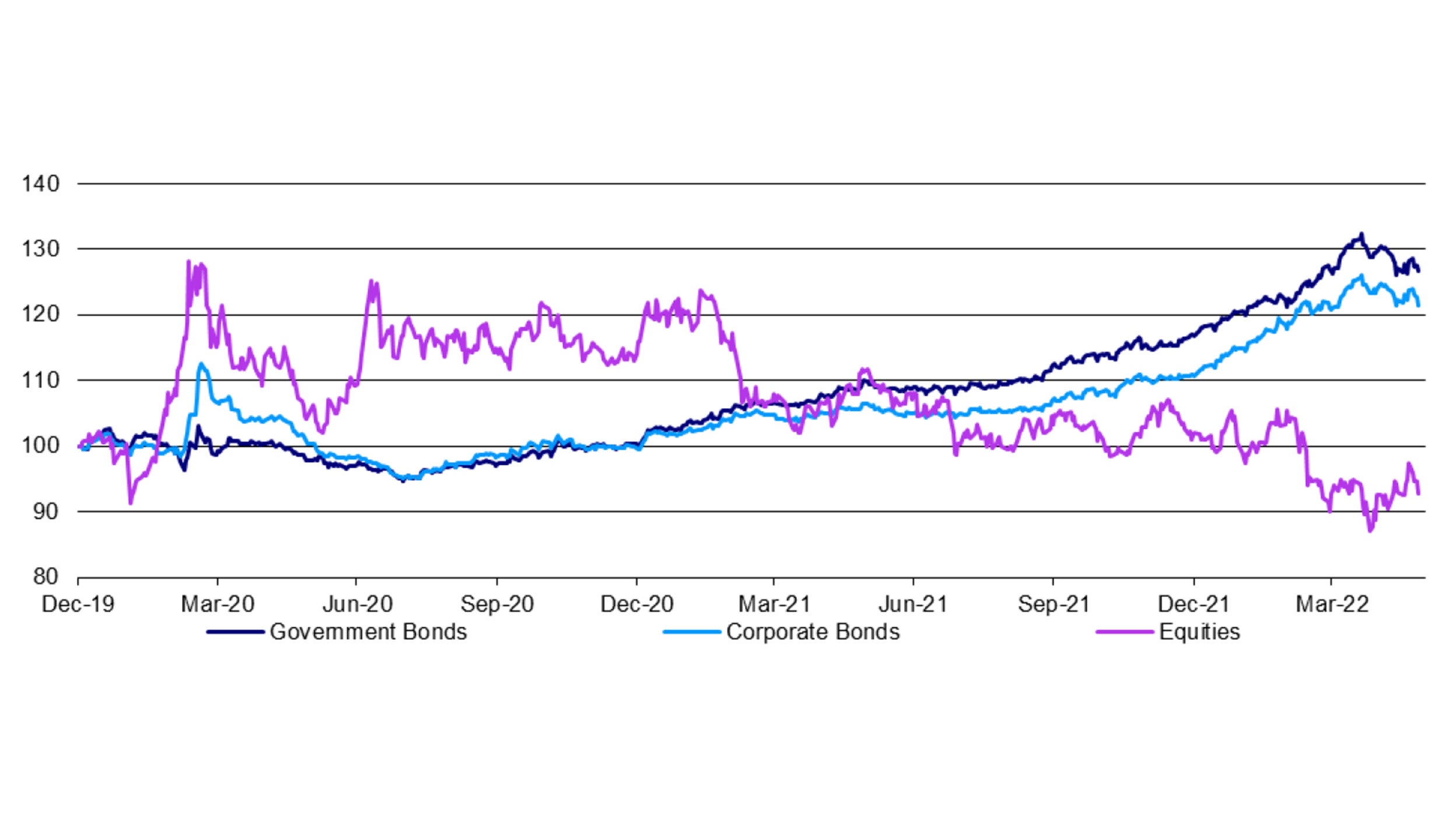

When it comes to the performance of Chinese assets, Figure 1 suggests that bonds and equities have gone in opposite directions since the end of 2020: bonds have outperformed global indices, while equities have underperformed. The relative strength of Chinese bonds reflects the relative weakness of the Chinese economy, in my opinion. After outperforming most other economies during 2020, China not only didn’t get the post-Covid rebound enjoyed by countries that had shrunk more, but it also suffered the impact of a deliberate clampdown upon the real estate sector. Hence, 2021 was a relatively difficult year, as reflected in the slippage in equities and the decline in bond yields implicit in Figure 1. A series of regulatory “surprises” further hindered the equity market.

Those relative performance patterns have continued into 2022, with People’s Bank of China (PBOC) loosening (while other central banks tighten) causing a decline in bond yields. At the same time, concern about the effect of Covid-related lockdowns has driven the equity market even lower and caused it to underperform major indices in the rest of the world (see the year-to-date data in Figure 4).

Interestingly, Figures 1 and 4 show a recent reversal in those trends, though it is to be seen if that continues or whether it is just a dead-cat bounce.

Note: past performance is no guarantee of future results. Daily data from 31 December 2019 to 26 May 2022. In each case, the respective Chinese total return index is divided by the world total return index and rebased to 100 as of 31 December 2019. “Government Bonds” is based on ICE BofA China Government Index and ICE BofA Global Government Index. “Corporate Bonds” is based on ICE BofA China Corporate Index and ICE BofA Global Corporate Index. “Equities” is based on Datastream China-A DS Market Index and Datastream World DS Market Index. Source: ICE BofA, Refinitiv Datastream and Invesco

On the fixed income side, 10-year government bond yields in China recently dipped below US levels. This may be justified by the fact that inflation is much lower in China (2.1% in April versus 8.3% in the US) but it is the first time since mid-2010 that it has been the case. Given the apparent reticence of the PBOC to ease aggressively, I wonder if Chinese bond yields are not about to bottom, just at the moment I expect the Fed to start sounding less hawkish (thus allowing US yields consolidate recent gains). Hence, I think we may already have seen the best of Chinese bonds relative to other markets.

On the equity side, there are plenty of reasons for caution, as I have been reminded during recent meetings (and not only in the Middle East). A recurrent theme is the weakness of the Chinese economy (retail sales were down 11.1% in the year to April, for example), particularly due to the zero-Covid policy that has led to lockdowns in regions reckoned to account for 30%-40% of GDP – see this from CNBC. Having seemed to handle the pandemic better than most other countries, the highly contagious Omicron variant has made China a victim of its own success. Immunity rates would appear too low, both because not enough people have had Covid and not enough are effectively vaccinated. Hence, China now finds itself where most other countries were at the start of the pandemic, leaving lockdowns as the only tool available to limit the number of deaths. Rolling out effective vaccines will be critical in opening up the economy. This being said, Shanghai now appears to be reopening, though Beijing is going in the other direction (luckily, the latter is less important to the economy).

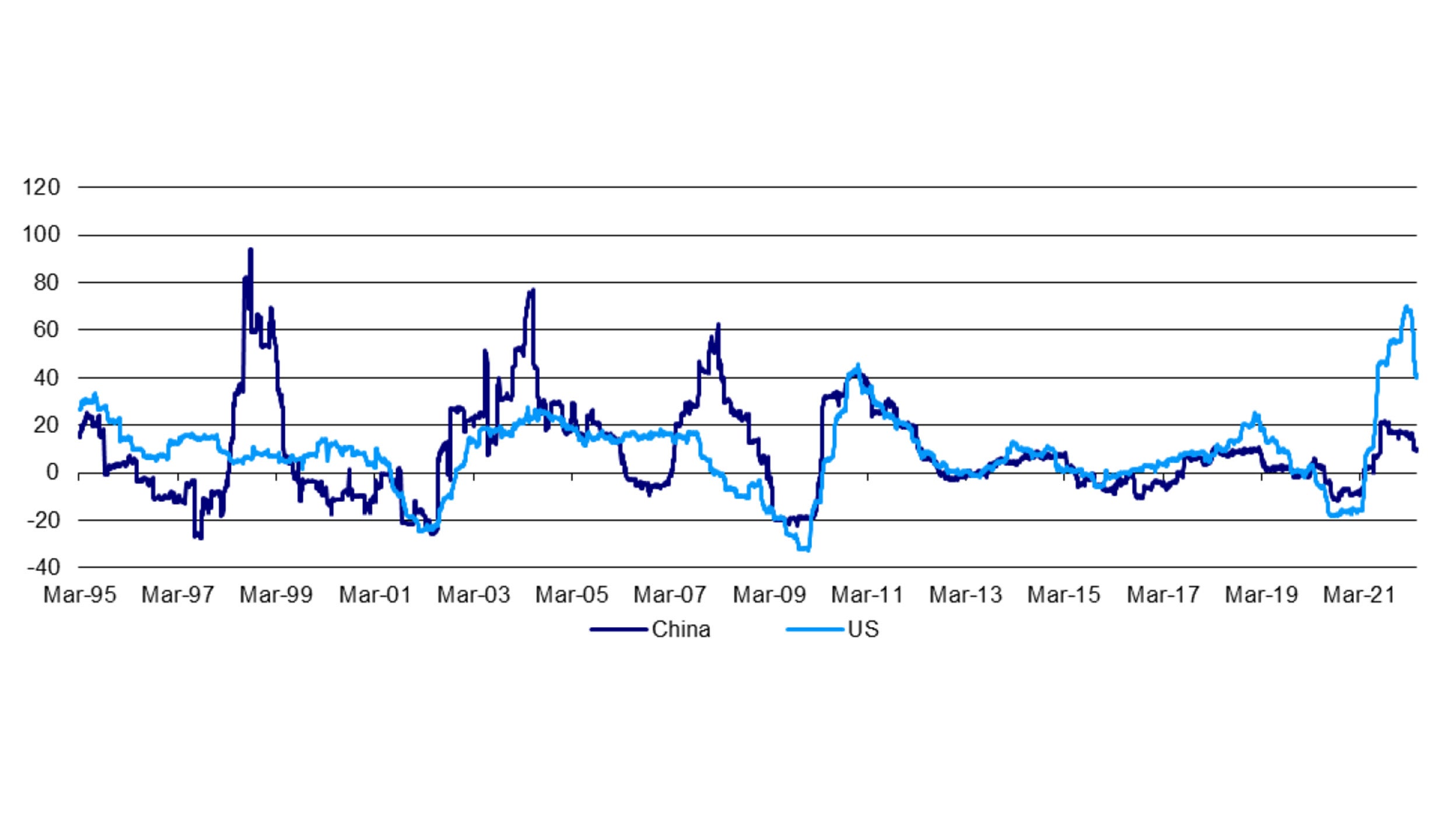

Recent economic data has been weak (industrial production was down 2.9% in the year to April). Not surprisingly, this is dampening corporate profits, which are perhaps also being squeezed by rising commodity prices (industrial profits were down 8.5% in the year to April). Figure 2 shows that full-market profit growth peaked at around 22% in October 2021 and has since slipped to 9% year-on-year (as of 26 May 2022). US profit growth may have fallen even further but from a higher starting point.

Leaving aside concerns about the current economic cycle, many worries are being expressed about the risk of sanctions as a result of geopolitical tensions. These could damage China’s economy but could also involve restrictions upon the ability of foreigners to invest in China (see, for example, the current restrictions imposed by the US on investment in certain Chinese companies). I imagine those concerns would increase if there were a return to a Trump presidency.

Of course, China has itself acted in ways that discourage investment from overseas. In particular, there were the surprise regulatory changes that were announced in 2021 in the technology and education sectors. However, recent evidence suggests a corner may have been turned, with a more flexible approach to the tech sector.

Concerning the other worries listed above, we suspect a more flexible approach may be adopted towards the management of Covid after the re-election of Xi as president in October (which, though not guaranteed, we assume will happen). This will presumably involve a large-scale rollout of vaccines, particularly to the large part of the elderly population that remains unvaccinated (by their own choice). It also appears that the generous fiscal support allowed by the centre has not yet been used by local governments. We presume this is due to a lack of confidence brought on by Covid lockdowns and assume a fiscal boost from this direction during the second half of the year.

Note: daily data from 31 March 1995 to 26 May 2022. Based on Dastream China-A DS Market and US DS Market indices (with EPS derived from the price index and price-earnings ratios). Source: Refinitiv Datastream and Invesco.

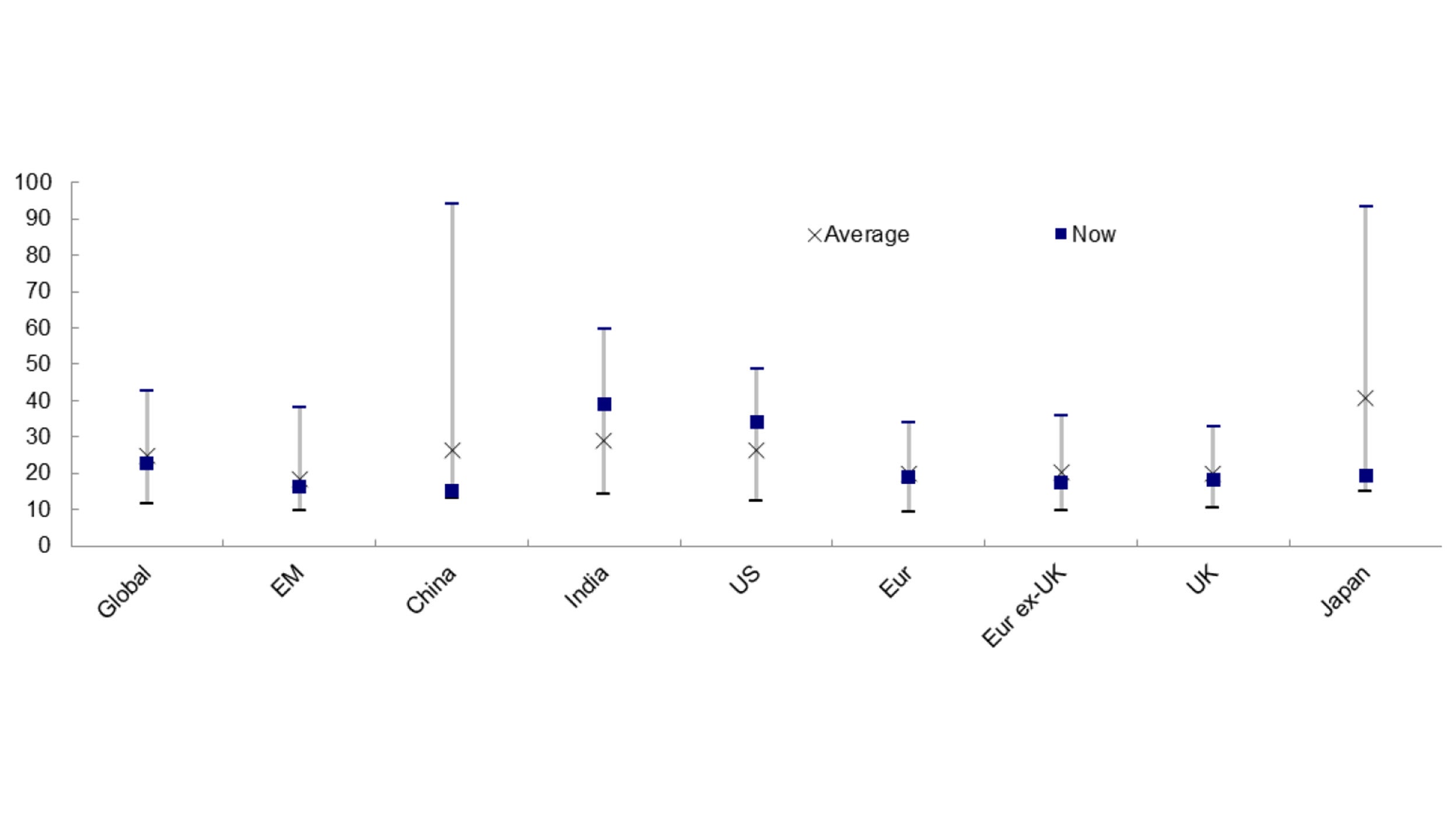

All of the above reasons for optimism are merely opinions and may sound tenuous. Where I feel on safer ground is valuations. I work on the principle that the major determinant of investment returns over the medium term is the valuation of an asset at the time of purchase. Figure 3 shows that the cyclically-adjusted price-earnings ratio (CAPE) for Chinese equities (15.3) is currently the lowest among the markets that we cover and at the bottom end of its own historical range. On this basis, US and Indian equity valuations are at the other extreme.

Why the use of CAPE’s? Well, simple P/E ratios (today’s price divided by the most recent earnings) are extremely volatile due to the cyclicality of earnings (see Figure 2). Indeed, P/Es often rise in times of recession due to the collapse in earnings and are at their lowest during economic booms, just when the stock market may be about to peak. A CAPE smoothes out the earnings cycle by using a 10-year moving average of earnings as the denominator. Our research suggests that the predictive power of valuation ratios is improved when they are cyclically adjusted in this way, with the P/E ratio seeing the biggest improvement (versus other ratios such as price/book-value and dividend yield, which tend to have higher predictive power in the first place).

On this basis, I feel more comfortable holding equity markets that have a lower CAPE than usual, which is certainly the case for China. Even better, its CAPE is the lowest in absolute terms and, as outlined above, there are reasons to believe that some of the factors behind China’s equity market underperformance may be reversing.

I always felt that the enthusiasm for Chinese equities was overdone at the end of 2020. Likewise, I suspect that investors are now being overly cautious, which I believe has created an interesting entry point for what I think will become an important part of global equity benchmarks over the coming decades. We moved to an Overweight stance within our Model Asset Allocation in mid-March (see Figure 7) and, so far, we are happy with that decision.

All data as of 27 May 2022, unless stated otherwise.

Note: CAPE = Cyclically Adjusted Price/Earnings and uses a 10-year moving average of earnings. Based on daily data from 3 January 1983 (except for China from 1 April 2004, India from 31 December 1999 and EM from 3 January 2005), using Datastream indices. As of 26 May 2022. Source: Refinitiv Datastream and Invesco