Responding to the Covid-19 outbreak, the monetary and fiscal authorities of the developed world have almost uniformly introduced an array of measures to ease financial strains, support household and corporate incomes, guarantee loans and relieve unemployment.

The lockdowns implemented from March onwards caused huge declines in economic activity.

To enable households and firms to survive these government-mandated shutdowns, politicians felt compelled to compensate for lost wages and to support corporate finances.

These support schemes have been on an immense scale and have therefore led to correspondingly large increases in the outstanding amount of government debt.

At the same time, firms have drawn down credit lines at banks or issued corporate bonds to give themselves the liquidity to survive through the downturn.

The overarching question is, are the debt increases sustainable?

Furthermore, how serious will the burden on the taxpayers be in the future?

Can economic growth return to normal within a reasonable timeframe?

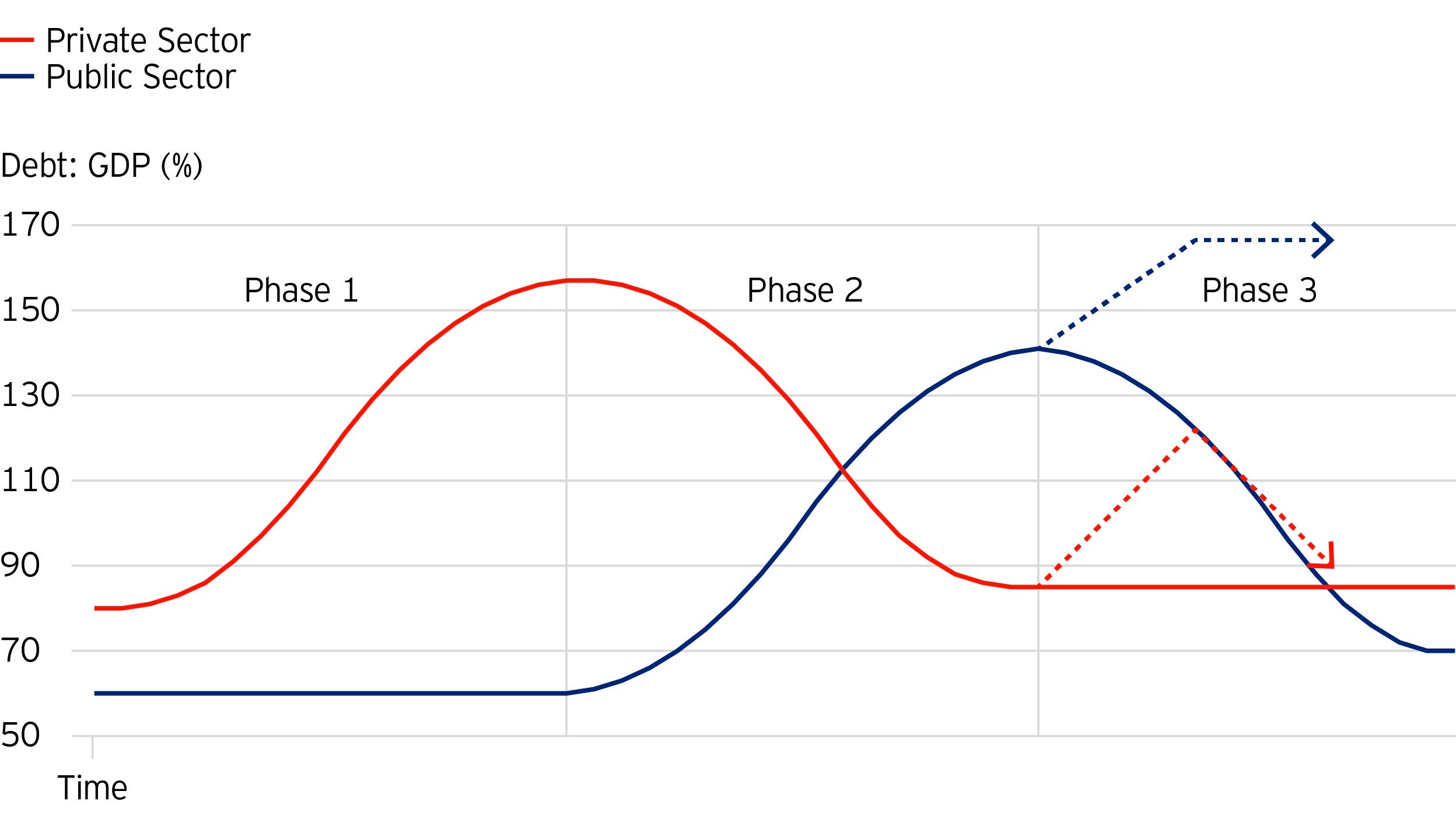

The model of a 3-phase debt crisis in Figure 1, which we have relied on as a template for much of the past decade since the Global Financial Crisis of 2008-09, was abruptly interrupted by the onset of Covid-19 in March, April and May 2020.

In what follows I will focus on the data for the US economy, but the same broad considerations apply to most other major economies or economic areas such as the UK or the eurozone.

Instead of the US economy showing a continuing debt work-out through Phase 3 as laid out in the original template, the coronavirus crisis and its financial consequences have produced a sudden change of direction for the debt ratios, as suggested by the red and blue dashed arrows.

The debt levels of both the private sector and the public sector have jumped.

The increase in private sector debt is mostly in the corporate sector, although this is generally an increase in gross debt as firms have borrowed in order to add reserves of cash and liquid assets to see them through the period of the pandemic.

In the US the federal government has responded by massively increasing its indebtedness in order to provide numerous grants of cash, subsidies and support facilities to companies and individuals (e.g. the stimulus cheques of $1200, the $600 per week increase in unemployment compensation and other benefits under the CARES Act).

However, in the case of the government much of this expenditure is an immediate cash outflow with no intent or prospect of repayment; there is no equivalent to corporate additions to cash reserves.

In other words, aside from some loans due for repayment under schemes such as the Paycheck Protection Program, the increase in federal debt is likely to be permanent.

Looking ahead, whereas the increase in all-government debt is likely to persist for many years (as suggested by the second blue dashed arrow in Figure 1), we expect the private sector to reduce its indebtedness over the next two or three years (as indicated by the falling second red dashed arrow).

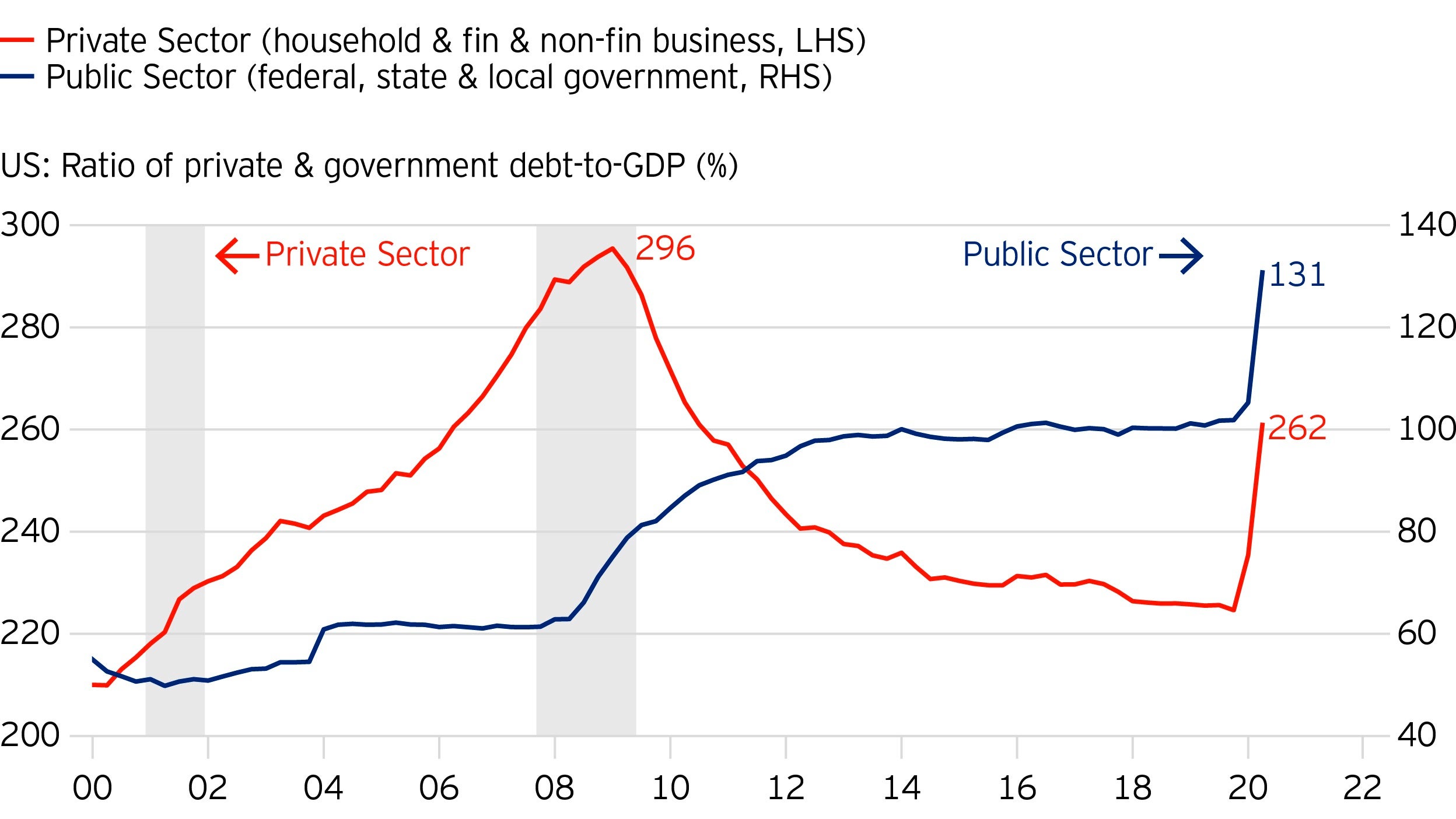

The US private sector debt ratio – which includes the debt of the household sector, non-financial business sector and financial sector – peaked at 296% of GDP in 2009 Q1.

A decade of de-leveraging enabled it to decline to 224% by 2019 Q4, a cumulative decline of 72 percentage points. But then, with the onset of the pandemic in March and April 2020, corporate borrowing and debt issuance surged, raising the gross private sector debt level to 262% in 2020 Q2, or by 38 percentage points from 2019 Q4.

Drilling down into the ratio of total private sector debt-to-GDP, it is the non-financial corporate sector that has seen the largest increase between 2019 Q4 and 2020 Q2, rising from 75% to 90%.

Meanwhile the financial sector debt-to-GDP ratio has risen from 77% to 89% and the household sector debt-to-GDP ratio has increased from 73% to 83%.

The steepness of the renewed jump in the private sector debt ratio in 2020 Q1 and Q2 is due to (a) increased borrowing by the non-financial corporate sector (in the numerator) and (b) the collapse of GDP (in the denominator).

I expect the US GDP will recover to about 95% of its pre-pandemic level by yearend, raising the denominator and prompting the private sector debt ratios to fall again.

The US public sector debt ratio - which includes federal, state and local government debt - began rising in 2008 Q3 at the start of the US recession of 2007-09, levelling out at around 100% of GDP between 2013 and 2019.

However, the emergency government spending prompted by the coronavirus crisis has now raised the all-government debt ratio from 102% in 2019 Q4 to 131% in 2020 Q2.

State and local government debt accounts for just 16% of GDP, and the federal component of debt is 115% of GDP.

Depending on the progress of the pandemic, total government debt ratio will continue to rise, though at a slower rate.

Again, as GDP recovers, the denominator will rise, prompting some decline in the public sector debt ratio, but probably not as much as the decline in the private sector.

Turning to the question of debt sustainability, we may question the conventional rules created during past periods of higher interest rates and higher inflation.

For example, under the Maastricht Treaty the EU adopted a government debt-to-GDP ratio of 60% as the maximum allowable for member states.

However, recent, current and (probable) future conditions of low inflation and very low interest rates support a case for government debt-to-GDP to remain more elevated than in the past, provided that (1) monetary policy ensures the continuation of low inflation, and (2) state sector activity in the economy is kept to a minimum in order to ensure the optimum allocation of private capital and resources, thereby allowing the government to raise revenues in line with GDP growth.[1]

The rule of thumb that applies is that as long as the government budget deficit (expressed as a percentage of GDP) is kept below the growth rate of nominal GDP, then it follows that over time the debt-to-GDP ratio will gradually decline.

Countries like the UK have experienced several examples of rapid, large-scale expansion of government debt relative to the size of the economy - for example after the Napoleonic wars, and after World War 1 and World War 2.

On each occasion, the high level of debt-to-GDP - which reached as high as 240%, twice today’s levels - was later reduced by a steady commitment to fiscal prudence accompanied by a sound monetary policy and low inflation.

As a result, the UK government was able to continue to borrow in financial markets without difficulty.

Governments rarely, if ever, repay debt. Their general strategy, even if it is not articulated, is to expand the nominal GDP in the denominator while reducing over time the additions to debt in the numerator by gradually reducing the size of the annual budget deficit.

In principle, and provided the two rules above are observed, it should be possible for developed economies to run annual budget deficits of 2-3% of GDP while still reducing their debt-to-GDP ratios.

[1] This analysis draws on an article by Forrest Capie et al in SUERF, the European Money and Finance Forum: https://www.suerf.org/policynotes/15239/a-sensible-fiscal-policy-for-the-sharp-rise-in-government-debt