A shift higher in rates

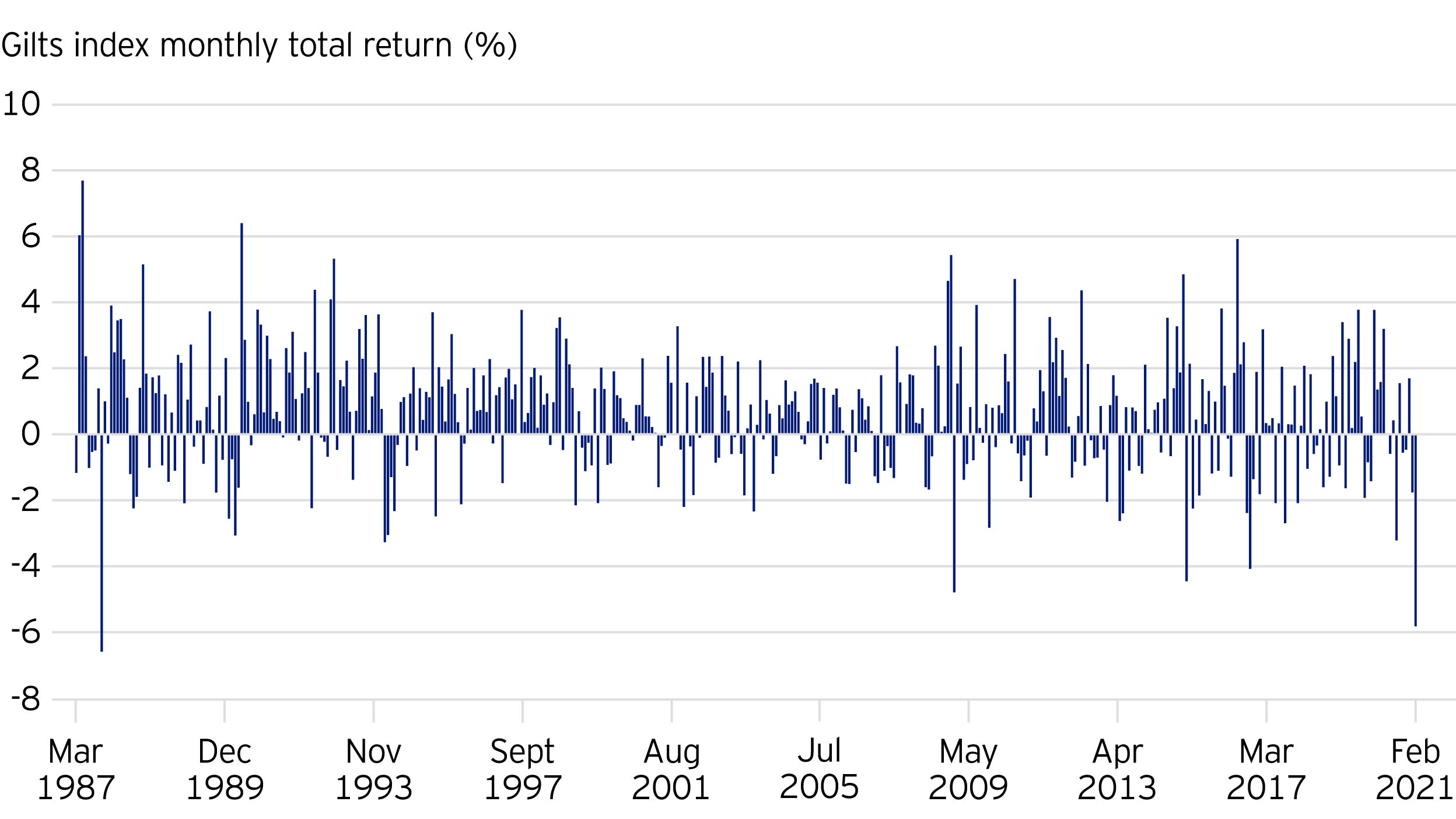

The gilt market has just had its worst month in over 30 years. What does this mean for investors in the wider bond market?

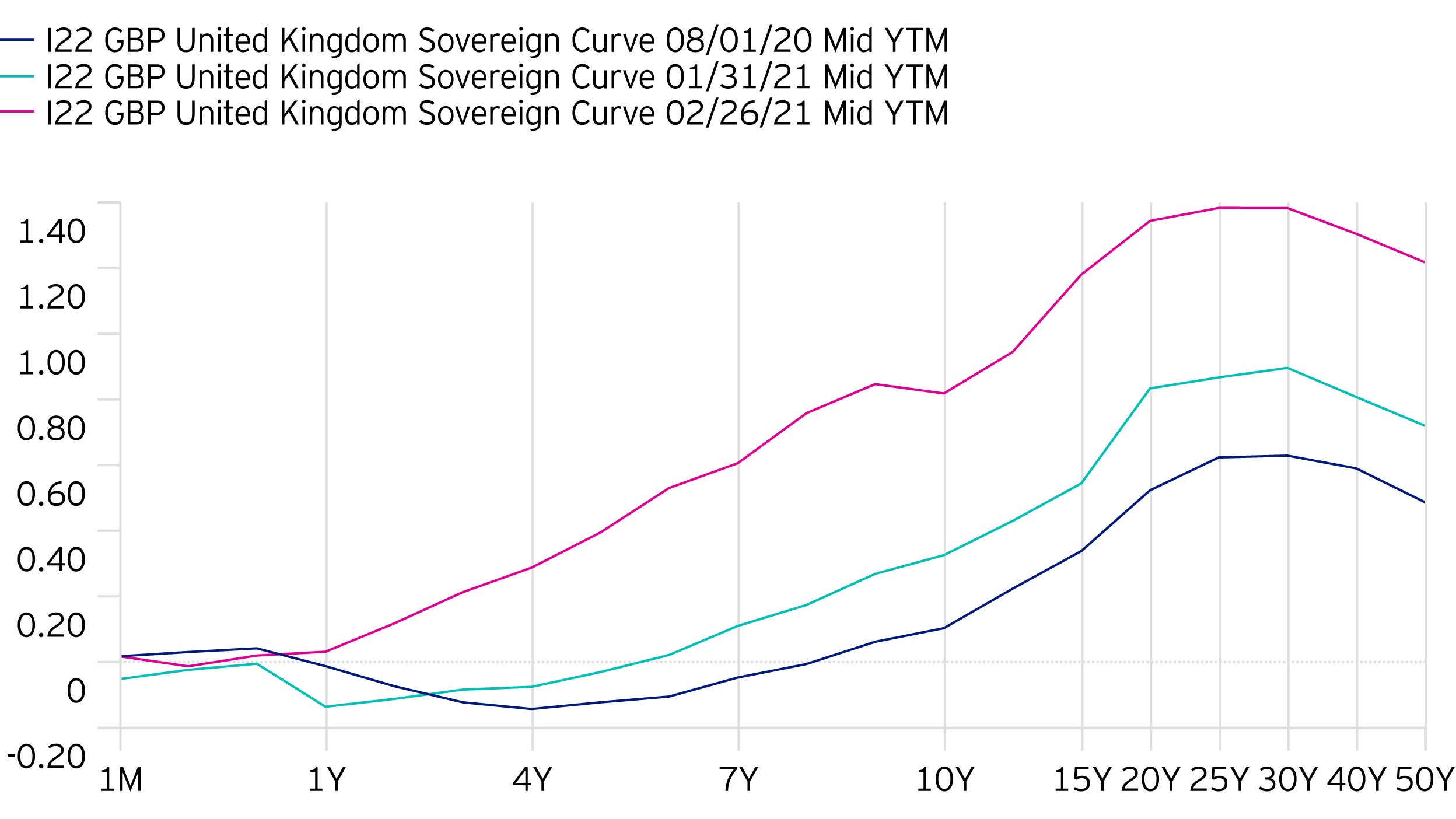

Over the past month the whole gilt yield curve rose, with longer bonds hit hardest. Evidence of pricing pressures is mounting and there have been some changes in central bank messaging. The market appears less tolerant of the very low gilt yields that have helped to support the wider investment universe in the last year.

In the 35-year history of the ICE BofA UK Gilt Index, February 2021 was the second worst month, with a total return of -5.82%. Yields rose and the curve steepened (+36bps at the five-year point, a return of -1.8%; +48bps at the 30 year, a return of -12.2%). Low yields offer a thin cushion against falling prices. The market’s -5.97% price fall was offset by only 0.15% of income.1

Gilt yields had been on a gently rising trend since August but February’s sell-off was much sharper. The short end is most influenced by official interest rates and here yields have remained close to zero. Further out, where yields are more a reflection of market expectations for growth, inflation and longer-term rates expectations, levels have moved considerably.

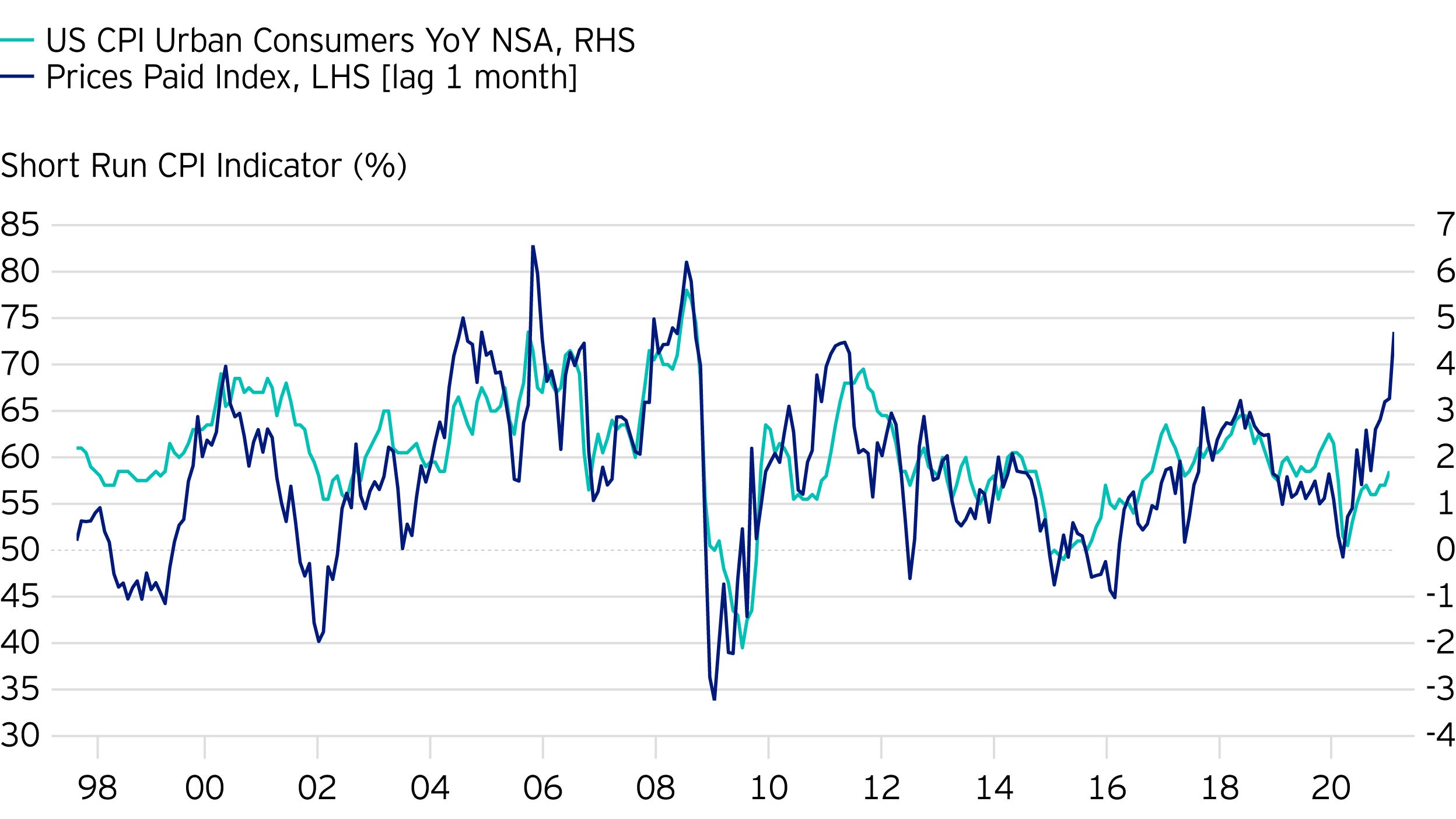

Some of the factors driving this are global. Headline developed market inflation remains low but as expectations for the emergence from lockdowns and a rebound in growth have grown, indicators of inflation have been rising. The chart below shows the recent uptick in the US Prices Paid Index and its strong leading relationship with wider inflation.

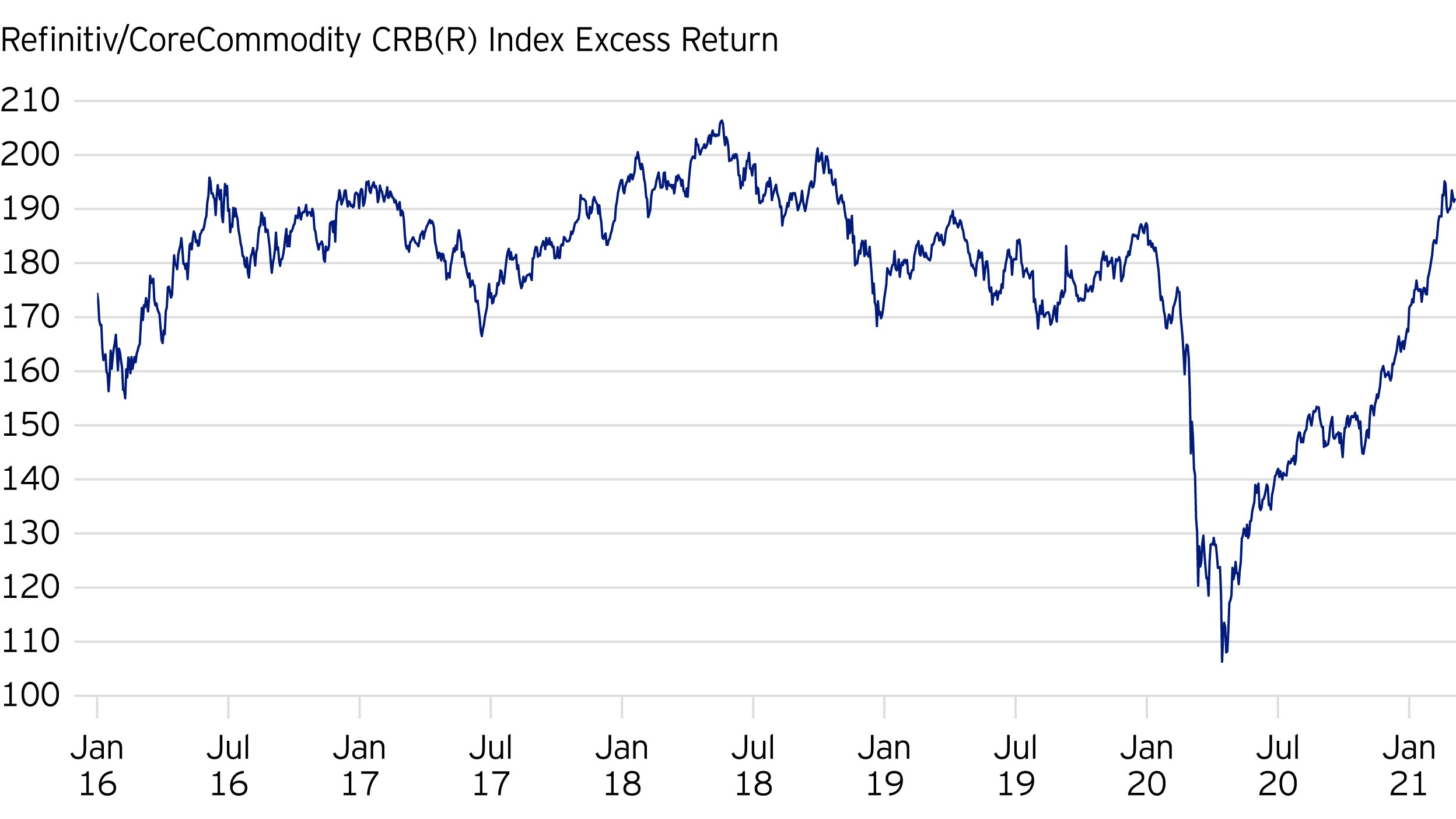

One very clear sign of price pressure is in the commodity market, where the CRB index has risen 32% since October.

Within commodities, industrial metals, associated with economic growth, have been strong. The price of copper jumped 15% in February and has rallied 61% over the last year to ten-year highs. Precious metals have rallied too, but much less so.

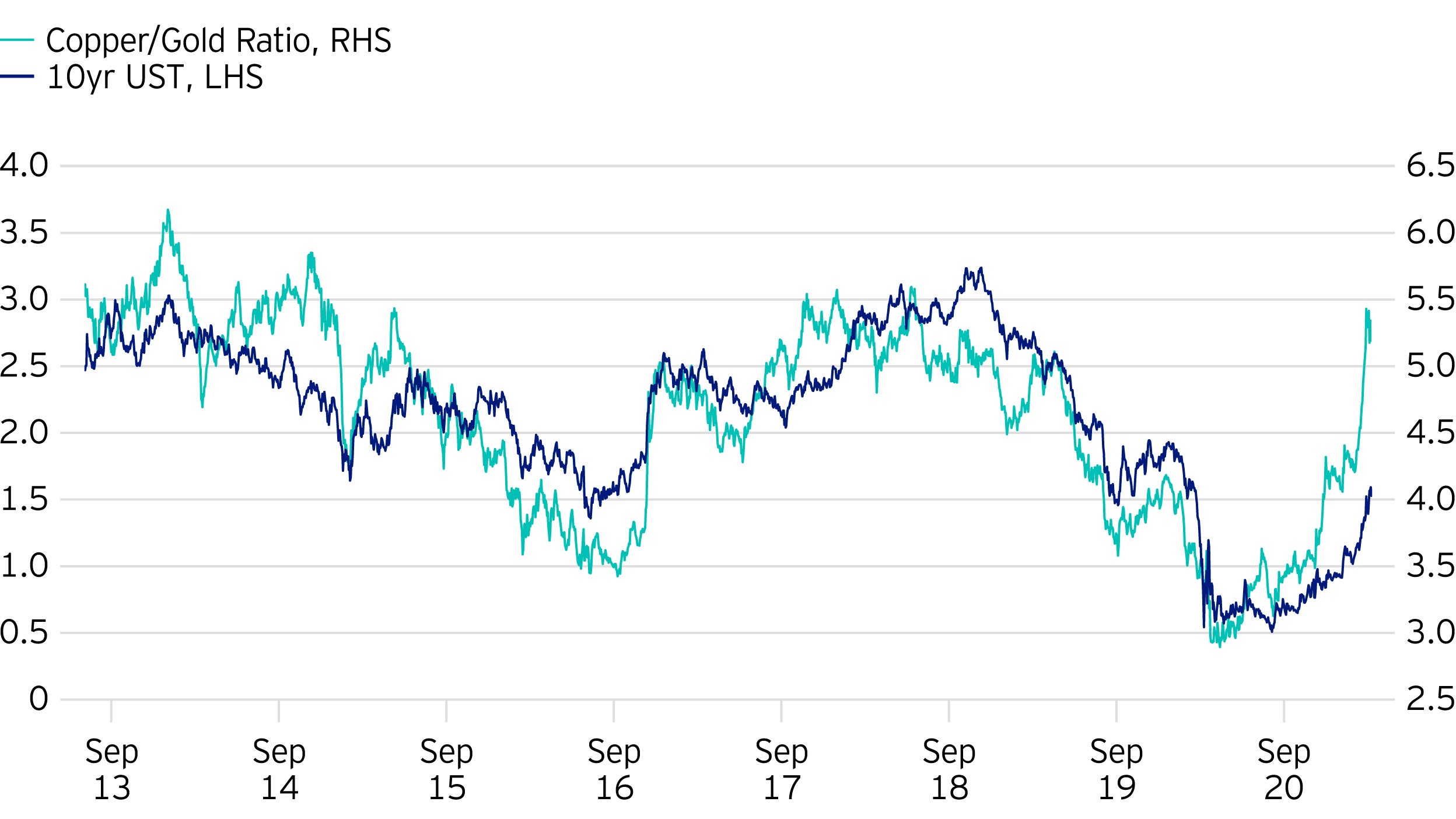

Historically, the relationship of the copper and gold prices has been strongly correlated with bond yields. The rationale for this is that the economic environment where demand for copper outstrips demand for gold is one where growth and eventually interest rate expectations rise.

There is also a logic to the anticipation of higher rates further out, and so a steeper curve. These indications of stronger growth and pricing pressure, even as the Biden administration’s $1.9tr stimulus package is finalised, appear to have done very little to reduce the commitment of the major central banks to maintain rates at the present, historically low levels.

If anything, the Federal Reserve’s rhetoric has been more explicitly pro-growth. Last year, the Fed re-calibrated its inflation target – emphasising that it wished to see inflation average 2% over time, not just hit that level briefly. This implies a willingness to see it overshoot before they will hike.

In recent weeks, Chairman Powell has repeatedly emphasised the employment element of the dual mandate. He has also suggested that the conventional unemployment rate understates true unemployment, highlighting higher levels in sectors of the workforce, including in minority ethnic groups.

Here in the UK, the Bank Rate remains 0.1%, unanimously re-affirmed at the latest meeting of the MPC. The Bank’s indication that it has no immediate intention to introduce negative rates has limited anticipation of any further cuts but the market continues to price in very little change for the next two years.

The combination of pro-growth policies and a tolerance for some pricing pressure and higher market yields is a mixed blessing for investment grade credit. Just as the Fed has a dual mandate of inflation and employment, investment grade corporate bonds have dual risk factors – duration and credit.

Economic growth will tend to boost corporate earnings, strengthening companies’ balance sheets and reducing credit risk. In the context of growth, higher prices are not negative and can, of course, be an outright benefit for some sectors. But rising government rates are a negative, reducing the relative value of the asset class.

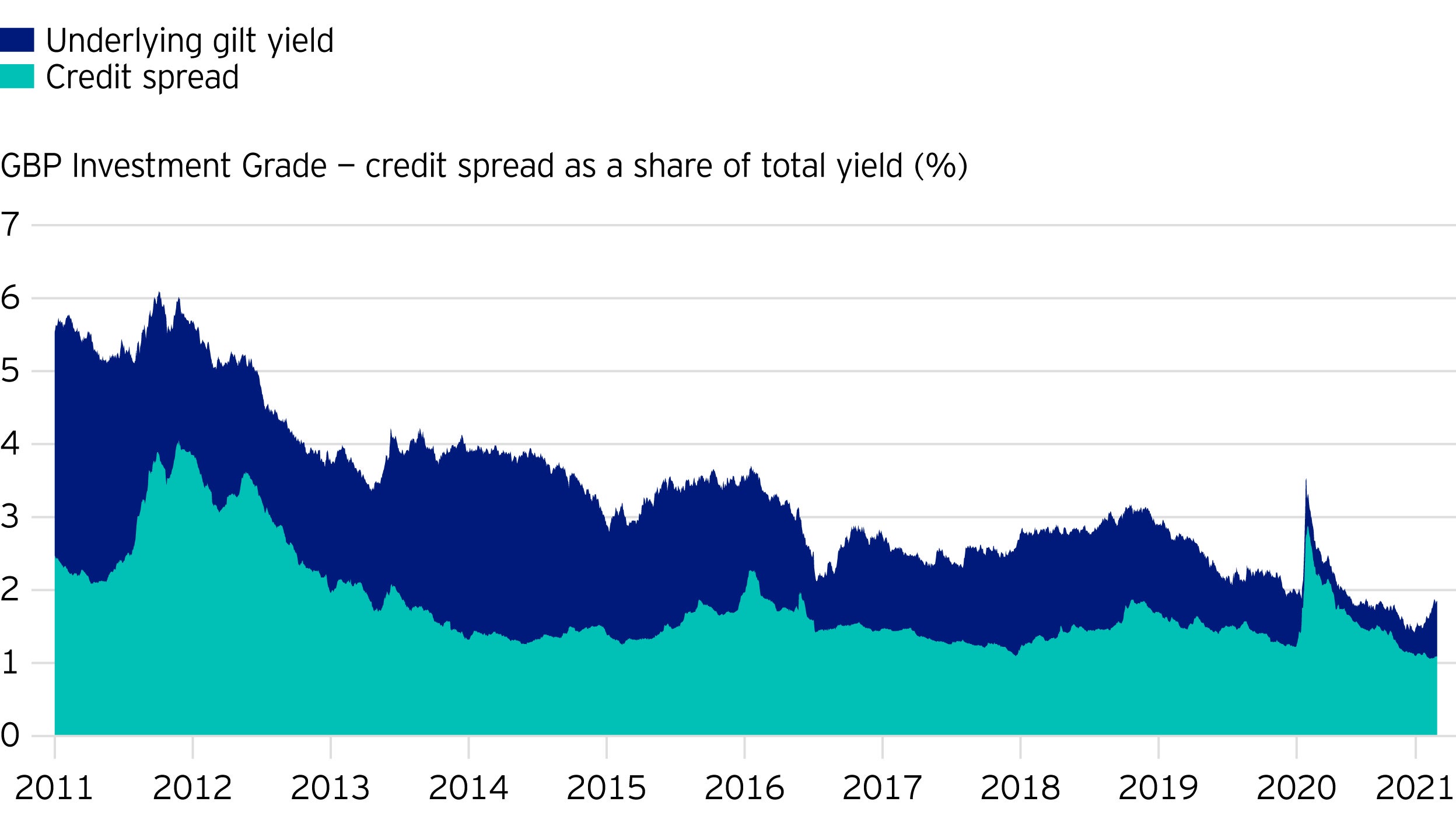

This chart disaggregates the yield of the sterling investment grade market over the last decade. It shows the extent to which the reduction of total yield over the last several years has been driven by falling gilt yields (one reason why we have tended to hold less duration than the market over the last few years).

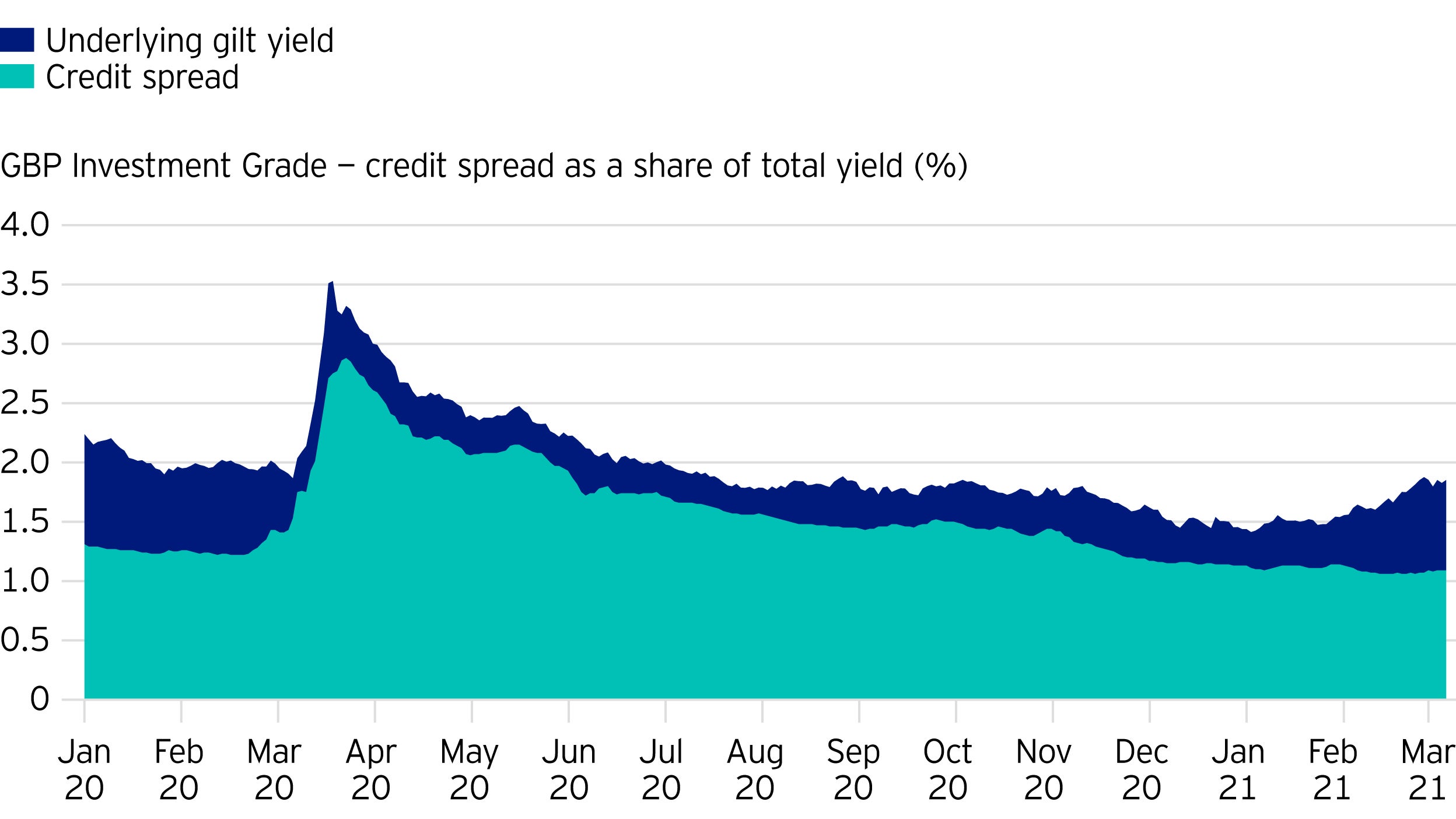

The second chart shows the same data but just for the last year. For much of this period, falling yields have been driven by a reduction in credit spread as the market demanded less and less compensation for default risk in a world of government support packages and negligible or negative risk-free rates.

In the last few weeks, credit spreads have continued to tighten. But returns for the investment grade market have been negative (-4.34% total return in the first two months of 2021). The total yield has risen from 1.36% to 1.80%.

We manage all risks actively. We want to be paid for the risk we take. That informs the extent to which we take credit and interest rate risk (duration).

For a long time, investors have not been paid much for the interest rate risk in the investment grade market. That has changed somewhat in these last few weeks, but we continue to prefer credit risk at these levels. If gilt yields move higher from here, we would be prepared to build more duration into our portfolios but the longer-term chart above shows how very low they still are.

The market’s credit spread is relatively low now. We are cautious but we still feel that we are receiving a reasonable level of compensation for the risk. Our main focus is on finding the bonds and the areas of the market where the compensation for risk is best.

Sector weights will always tend to be a consequence of bond selection for us, not a driver. But that is not to say that our assessments of companies are unaffected by more macro factors. Higher rates and steeper curves tend to boost the earnings of financials. Areas of the market are more and less sensitive to growth. As these factors shift, they will feed into our fundamental analysis.

Related articles

Keep up-to-date

Sign up to receive the latest insights from Invesco’s global team of experts and details about on demand and upcoming online events.