Many economists and market participants (including ourselves) have highlighted the extraordinary rates of government debt growth in response to Covid-19, especially in the US.

Federal government debt held by the public has increased by around US$3 trillion since the end of March 2020, as personal and corporate tax revenues have collapsed, while government outlays have surged.

Forecasts of general government debt across the developed economies have increased materially for the 2020 and 2021 calendar years, as highlighted by the table below.

Figure 1

| General government debt (% of GDP) | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|

| US | 109 | 141 | 146 |

| Euro area | 84 | 105 | 103 |

| Japan | 238 | 268 | 265 |

| UK | 85 | 102 | 101 |

Source: Consensus Economics, July 2020.

The sustainability of government debt depends on several factors including the stock of the debt outstanding, the level of interest rates, the term of maturity, the growth of the economy, confidence in the fiscal authorities and so on.

In this article, we introduce a simplified formal framework, and apply this framework to the US and the UK.

A formal debt sustainability framework

How sustainable are the recent rates of government debt growth?

This is of clear concern to many, and to analyse this question we will use the standard public debt sustainability analysis (DSA), which is based on the relation between the nominal interest rate on government debt (I) and the nominal growth rate of the economy (G).

The typical case is when interest rates are higher than the nominal growth rate of the economy (G), or in symbols: (I>G).

If, on the other hand, nominal GDP growth is consistently higher than the nominal interest rate on government debt, i.e. (G>I), debt sustainability is much less of a problem, as we will see.

Briefly, government debt becomes unsustainable when the government’s primary balance (the difference between taxes raised and non-interest expenditure) is not large enough to finance the increase in the interest cost of government debt (both measured as a percentage of GDP). Mathematically this can be written in a formula using four variables:

B = (I – G)*D1

Where B is the government primary budget balance

I is the average nominal interest rate charged on government debt

G is the nominal GDP growth rate

D is the stock of government debt

Let’s consider an example.

Suppose that the government primary budget balance is 1½% of GDP, nominal GDP growth is 5% year-on-year and the nominal interest rate charged on government debt is 7½%.

Using the above formula, we find that the maximum stock of sustainable debt is 60% of GDP:

D=B/(I-G) = 0.015/(0.075-0.05) = 60%

We can expand this single example into a matrix, with nominal interest rates in the columns and nominal GDP growth rates in the rows.

For the purpose of this exercise we have assumed that the interest cost of the government debt (I) is equal to the yield on the 10-year US Treasury bond.

For a given stock of government debt (in this matrix we have assumed 100% of GDP), for each given I and G there is a minimum required government primary budget balance (as a percentage of GDP) for debt sustainability.

Figure 2

Nominal GDP growth rate |

100% Debt-to-GDP | 0% | 1% | 2% | 3% | 4% | 5% | 6% | 7% | 8% | 9% | 10% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0% | 0.0% | 1.0% | 2.0% | 3.0% | 4.0% | 5.0% | 6.0% | 7.0% | 8.0% | 9.0% | 10.0% | |

| 1% | -1.0% | 0.0% | 1.0% | 2.0% | 3.0% | 4.0% | 5.0% | 6.0% | 7.0% | 8.0% | 9.0% | |

| 2% | -2.0% | -1.0% | 0.0% | 1.0% | 2.0% | 3.0% | 4.0% | 5.0% | 6.0% | 7.0% | 8.0% | |

| 3% | -3.0% | -2.0% | -1.0% | 0.0% | 1.0% | 2.0% | 3.0% | 4.0% | 5.0% | 6.0% | 7.0% | |

| 4% | -4.0% | -3.0% | -2.0% | -1.0% | 0.0% | 1.0% | 2.0% | 3.0% | 4.0% | 5.0% | 6.0% | |

| 5% | -5.0% | -4.0% | -3.0% | -2.0% | -1.0% | 0.0% | 1.0% | 2.0% | 3.0% | 4.0% | 5.0% | |

| 6% | -6.0% | -5.0% | -4.0% | -3.0% | -2.0% | -1.0% | 0.0% | 1.0% | 2.0% | 3.0% | 4.0% | |

| 7% | -7.0% | -6.0% | -5.0% | -4.0% | -3.0% | -2.0% | -1.0% | 0.0% | 1.0% | 2.0% | 3.0% | |

| 8% | -8.0% | -7.0% | -6.0% | -5.0% | -4.0% | -3.0% | -2.0% | -1.0% | 0.0% | 1.0% | 2.0% | |

| 9% | -9.0% | -8.0% | -7.0% | -6.0% | -5.0% | -4.0% | -3.0% | -2.0% | -1.0% | 0.0% | 1.0% | |

| 10% | -10.0% | -9.0% | -8.0% | -7.0% | -6.0% | -5.0% | -4.0% | -3.0% | -2.0% | -1.0% | 0.0% |

Source: Invesco as at July 2020.

To illustrate the concept, suppose that interest costs were 2% (which is where the yield on the 10-year Treasury bond might be in a year or two) and the nominal GDP growth rate was 4% (composed of 2% real and 2% inflation), then the primary budget balance as a percentage of GDP can be -2.0%.

In other words, given this combination of I and G and an outstanding debt stock of 100% of GDP, the government can still afford to run a primary deficit of 2% of GDP.

Historic government financing pressures

The quantity (I – G) might at first glance be difficult to conceptualise, and how this quantity has behaved over time has indeed changed.

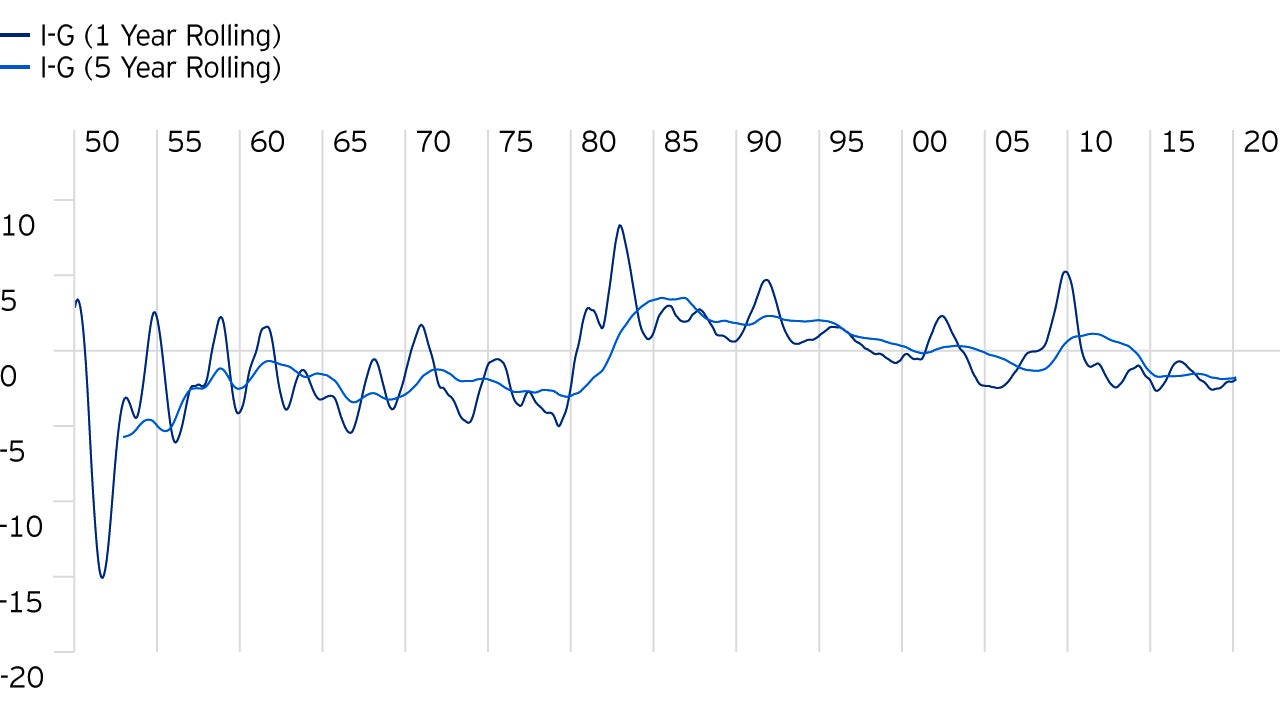

Figure 3 tracks the quantity (I – G) for the US economy (although the analysis can be applied to any economy) from 1950 to 2020:

Generally, the quantity (I – G) tends to fluctuate around zero and has averaged around -70 bps since 1950.

There are periods, however, where this quantity can spike in the short and medium-term, for example in the mid-1980s and in the period following the 2008/09 GFC.

Projecting forward over the next few years it is possible that due to current rapid money growth, inflationary pressures will build, while real GDP growth remains subdued.

Under these conditions, it is conceivable that interest rates could rise ahead of inflation, so that the quantity (I – G) could move higher, putting pressures on government debt financing and making the 100% debt-to-GDP ratio less sustainable.

Source: BEA, Macrobond. July 2020.

Conclusion

What does all of this mean for the future?

Nominal GDP growth at a higher level than interest rates is highly likely for the foreseeable future, but if excessive money and credit growth persist for more than a couple of years, interest rates may rise above nominal GDP growth rates.

In the US, broad money growth has reached historic highs of 23% year-on-year.

The Federal Reserve has pledged to continue indefinitely with its current pace of securities purchases of around $120 billion per month.

If this pace of money growth is sustained, higher inflation could become embedded after a couple of years.

This would push the (I – G) quantity higher, perhaps reaching around 3% if previous episodes of higher interest rates serve as a guide.

In this hypothetical situation, a period of fiscal austerity and monetary restraint would be warranted if government debt sustainability is a political objective.

In the UK, the latest Fiscal Sustainability Report by the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) includes a central Covid-19 scenario which predicts that the UK government will have to run at most a primary deficit of 3% in order to stabilise the stock of government debt2.

Baked into this analysis are low interest rates up until 2025, and if this is the case then there will be little pressure on financing the stock of government debt.

However, if interest rates do rise materially, the primary deficits will have to be lower to assure sustainability.

Since the interest rate outlook is tied to the rate of money growth, it is reassuring that the Bank of England’s recently announced asset purchases of £300 billion represent a much more moderate balance sheet expansion in comparison to the Federal Reserve, and there is no plan as of July 2020 for indefinite asset purchases akin to the Federal Reserve or the European Central Bank (ECB).

Another concern is the overall average maturity of government debt, which varies massively from country to country.

For example, in the UK the average maturity of government debt is over 11 years, whereas in the US the average maturity of government debt is slightly over 5 years.

Governments with a shorter average maturity of outstanding debt face higher rollover risk.

It follows that whereas the UK government has “locked in” lower interest rates for a long time, the US government will be more susceptible to rollover risk when new government bonds are issued.

The analysis in this paper has a relatively large margin of error, especially with respect to the development of interest rates across developed economies.

Reflecting this, there is a spectrum of potential outcomes as the global economy emerges from the COVID-19 pandemic recession.