Assessing the potential for rising inflation and higher commodity prices begins with an understanding of deflation and the role debt plays between these two contrasting economic regimes.

High levels of debt, especially unproductive debt that has low or no cash flow payback, can have a suppressing effect on economic growth. Productive debt can be defined as borrowing that supports projects that generate enough cash flow to repay the debt. Conversely, unproductive debt includes lending to high-risk corporate entities and/or spending on social or military initiatives, however worthy, that have not historically generated enough additional economic activity to service the incremental debt.

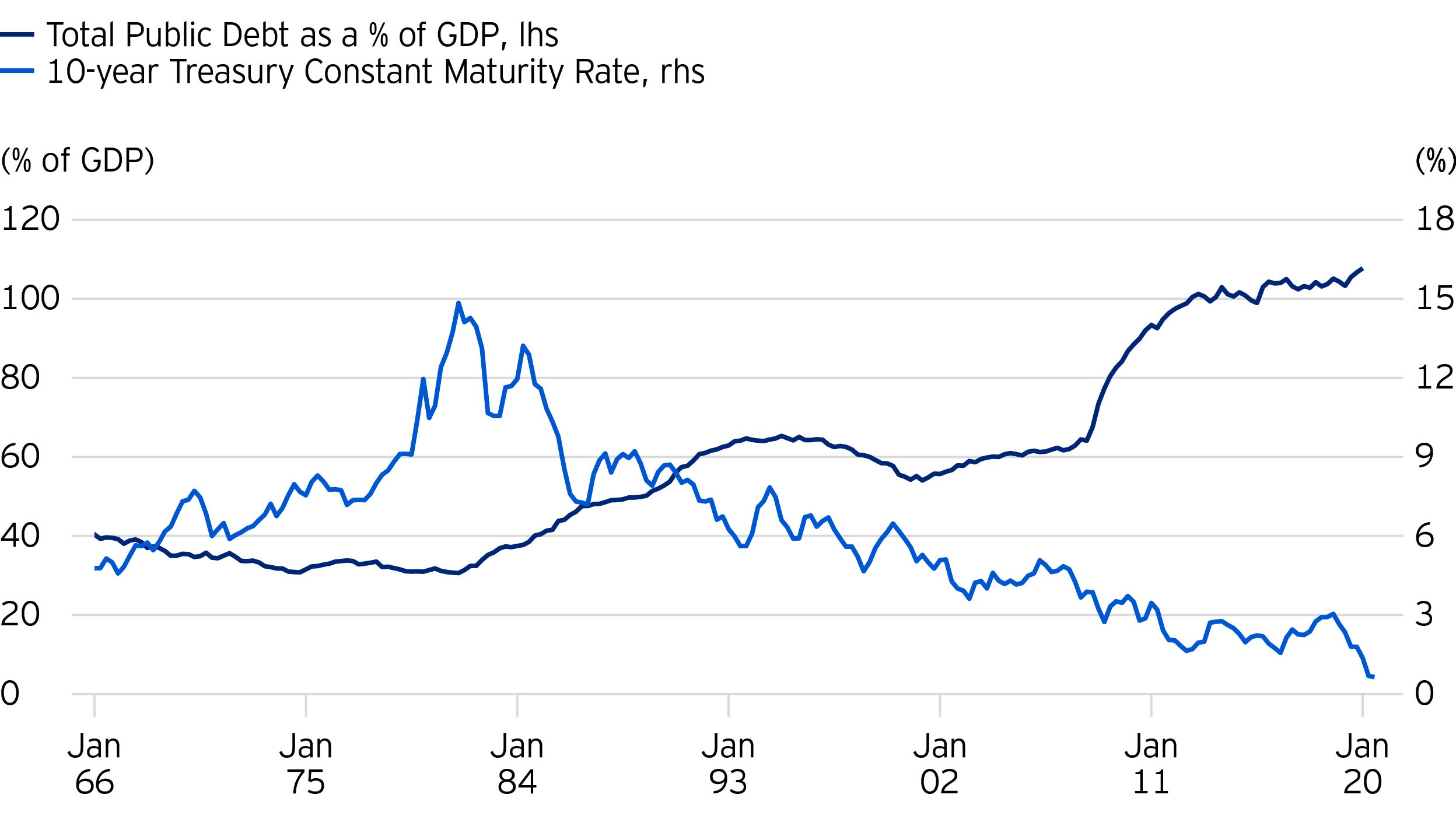

Demographics compound the problem of unproductive debt, as more individuals reach retirement age. Some economists point to low interest rates and reduced money velocity as proof that the debt burden is presently/already too high, which is leading to lower rates of growth and inflation. The chart below demonstrates this point with the blue line showing the rising debt burden (debt/GDP) and the green line showing the declining level of interest rates.

The case for inflation stems from the pernicious effects of deflation on the economy. A deflationary debt collapse is the worst-case scenario for policy makers because it risks triggering a long and deep depression characterized by chronic high unemployment, increased corporate bankruptcies and poor stock market returns. Therefore, inflationary policies are favored by both fiscal and monetary authorities to both reflate the economy and devalue the debt burden via currency debasement. Historically, inflation typically results when markets lose faith in government liabilities alongside the occurrence of commodity supply shocks.

The first potential source of inflation, the risk of investors losing confidence in US government liabilities, is linked to the federal debt and deficit. The US fiscal deficit was already $1 trillion prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and is currently on pace to reach nearly $4 trillion by the end of 2020 (source: https://www.cbo.gov/publication/56335). With 2019 tax collections estimated at $2 trillion, an additional $4 trillion must be raised to cover the shortfall. But there are only three ways to finance a deficit: taxes, borrowing and monetary policy actions.

Collecting another $4 trillion in taxes is not feasible economically or politically, even if taxes are raised to some degree. It is also unlikely that borrowing from non-bank entities such as individuals, asset managers, pension funds or foreign nations will be able to fill the gap because lower yields will reduce the appeal of investing in these debt issues.

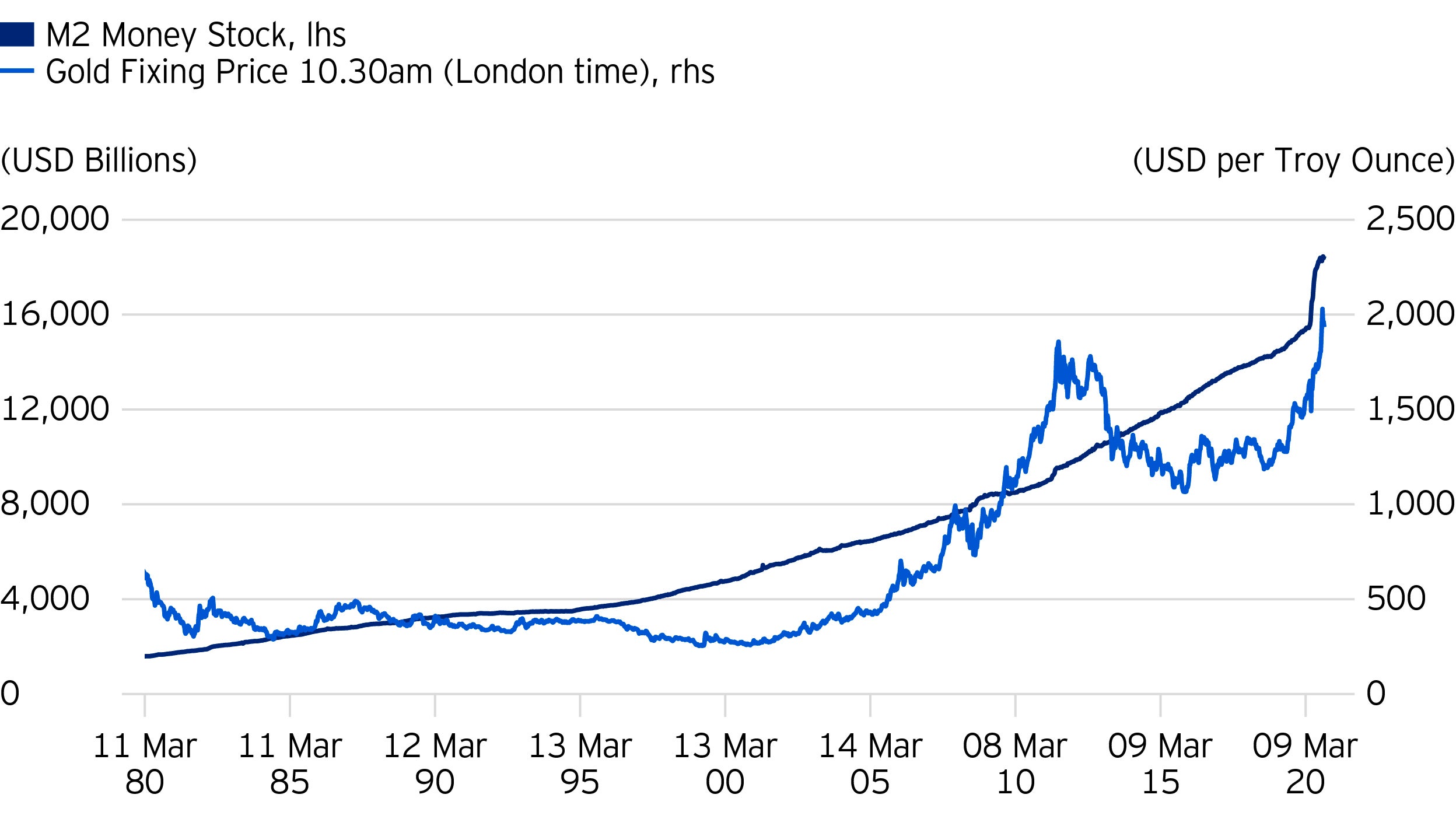

Monetary policy then becomes the most viable solution. This involves lending from banks and central banks, both of which create new currency to buy the newly issued government debt. Central banks will also maintain artificially lower interest rates to ease the nation’s existing debt burden; however, this adds to the risk of inflation through a weaker dollar. As money supply increases, higher gold prices are often cited as an early warning indicator that investors seek a store of value to protect them from inflation induced by the declining purchasing power of the nation’s currency.

Advocates for inflation will argue that rising gold prices are the first warning sign that investors are seeking protection from currency debasement. The chart below demonstrates the longer-term tendency for gold prices to rise with the money supply.

Commodity supply shocks are the second source of potential inflation. The prolonged commodities bear market only increases the risk of future supply/demand imbalances. “Low prices are the cure for low prices” is a common refrain in commodity markets because low prices change the behavior of both producers and consumers. Low prices not only result in lower production, but also reduce the available investment required to find replacement sources of supply.

For many years, producers have been reducing both production and capital investment as lower prices have persisted. Regulation poses another risk to maintaining supply/demand balance. Depending on location, the administrative and environmental permits required for operation often result in a gap of seven to 20 years before new production can come online after initial discovery. Additionally, because shutting down production and waiting for higher prices is not an economically viable option, producers engage in a technique called high grading, which involves producing only from the highest quality, lowest cost extraction sources.

However, after years of engaging in this practice, many producers have depleted their high grades, leaving only lower quality, higher cost sources of production. Further supply-side vulnerabilities arise from the trend toward deglobalization, which has been accelerated by COVID-19, as many nations look to relocate or even onshore supply chains. A world with reduced global trade and weaker trade interdependence increases both production costs and geopolitical risks. Given that many commodities are produced in politically unstable parts of the world, the risk of supply shocks and higher prices cannot be discounted.

Despite the deflationary forces that have had the primary influence on economies and asset prices, it’s important to consider that policy makers view inflation as the cure for deflation. Inflation is a part of the economic cycle that can be induced by policy, as well as by the forces of supply and demand.

Managing a multi-asset portfolio involves navigating the effects of growth and inflation. When slowing growth is the market’s primary concern, high-quality government bonds are the key source of portfolio diversification; however, when concerns shift to inflation, financial assets suffer and real assets such as commodities become an essential source of diversification as well as a total return opportunity.

As the chart below indicates, asset classes tend to rise and fall due to changes in growth and inflation. When the market is focused primarily on growth, bonds become the best diversifying asset; however, when inflation becomes a concern, commodities become the primary diversifier due to the negative effect inflation has on both stocks and bonds.