Asset allocation Capital market assumptions | Q1 2025

Invesco Solutions develops capital market assumptions (CMAs) that provide long-term estimates for the behaviour of major asset classes globally.

Since the global financial crisis (GFC) of 2008, the central banks of the major developed countries across the globe have pursued an extreme monetary policy. The extent, both in terms of size and duration, has gone well beyond what anyone could have envisaged. But what have been the unintended consequences of such an extreme policy?

There is an extreme disparity of valuation within the market which has been widening for some time. Whilst we are less worried about overall market valuations, we believe aggregate multiples are masking a huge skew within the market itself and that skew is itself a risk. There are major risks in some sectors and stocks where the consensus is, to our minds, dangerously complacent. Simultaneously, we see much more compelling medium-term rewards in parts of the market which are a long way away from most investors’ comfort zone. David Bowers, ASR’s strategist recently wrote;

David Bowers, ASR’s strategistIt is not the risky calls that damage portfolios the most – if you know something is risky you can plan accordingly. What causes the greatest damage is something you assume to be safe that turns out to be nothing of the sort.

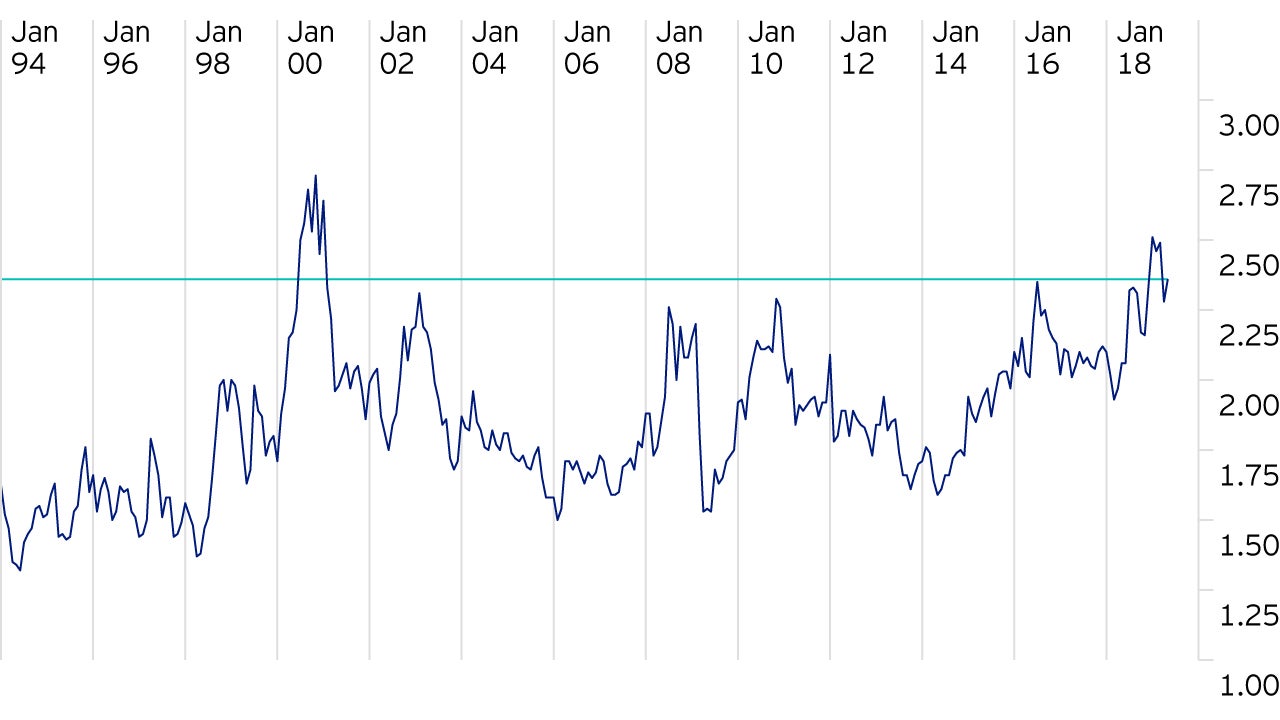

The winners of extremely accommodative monetary policy over the past decade have been the bond market and equities that most represent its qualities (‘bond proxies’ i.e. Long Duration, Stable, ‘Quality’). The losers have effectively been short-duration (‘bond hedges’ i.e. Cyclicals, Financials, ‘Value’). This has led to valuations for the former reaching all-time highs as investors rush towards perceived safety and away from economic sensitivity.

Some market commentators highlight that when one looks at the Quality/Value factor valuation gap measured by PE it is nowhere near as extended as 1999/2000. Whilst on a pure PE basis valuation don’t look as extended, we note, there is a meaningful difference between now and the last market valuation bubble (seen in the late 1990s); leadership today encompasses companies with earnings, versus companies trading in clicks and eyeballs. This makes just looking at earnings for a valuation anchor too simplistic. When one looks at a wider range of comparable measures, then a very different pattern emerges – one which suggests that we are in very extended territory indeed.

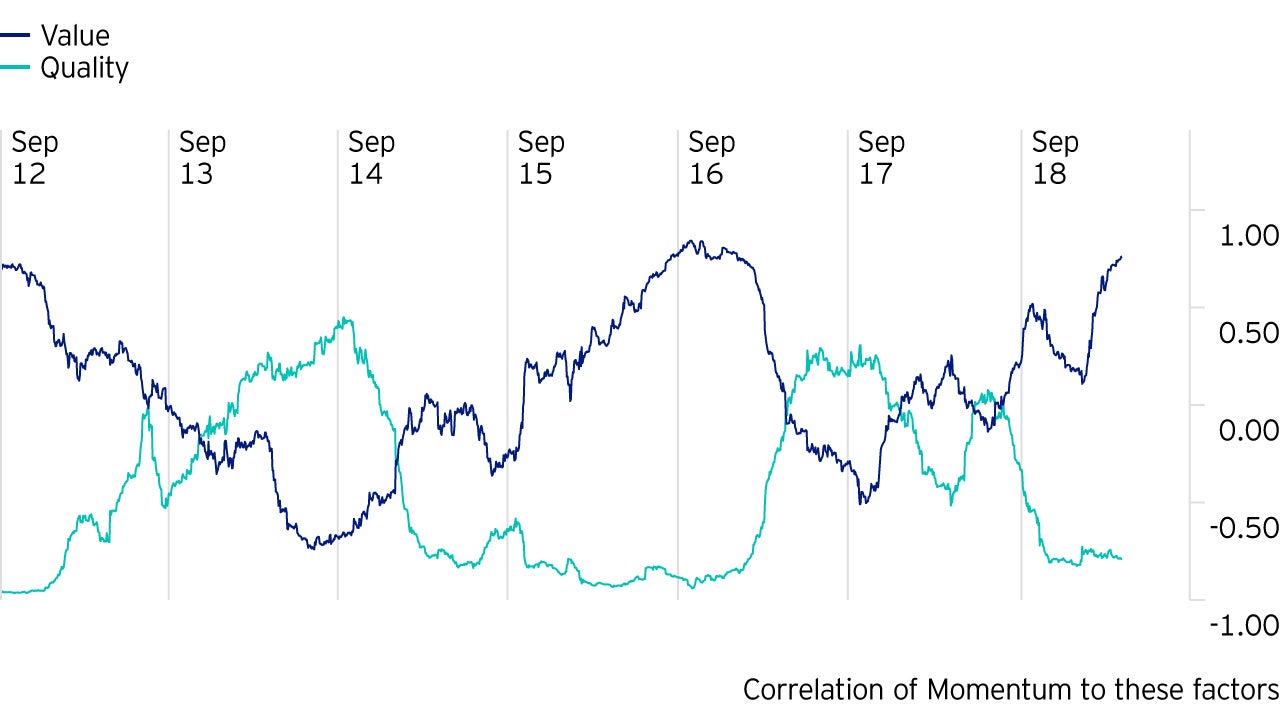

The effect is exacerbated by crowding – momentum strategies can inform as to whether there is a strong pattern to where the incremental dollar is being invested. It is clear that trend followers seem very certain that the winners can keep winning.

It is a road well-travelled to refer to the veteran investor, John Templeton, who suggested that the four most dangerous words in investment were, ‘It’s different this time’. There is, however, a growing chorus of those who are proposing exactly that – that we are in a different growth, pricing, and policy regime which renders past relationships with regard to valuation obsolete.

Since the GFC, the central banks of the major developed countries across the globe have pursued an extreme monetary policy. With debt levels so extended post crisis, there was no capacity to implement fiscal tools – indeed a program of austerity was embarked upon on a widespread basis - leaving Central Banks as the main agents of the financial rescue package. The extent, both in terms of size and duration, has gone well beyond that which the protagonists would have envisaged when it was first put in place.

At the same time, policy makers and regulators have sought to ensure that nothing like the GFC happens again. To that end, capital requirements for the biggest sinners of the previous cycle, the banks, have been ratcheted up in the pursuit of an assurance that never again will tax payers be required to pay for the sins of the ‘Masters of the Universe’.

On a holistic basis, the ‘success’ of these strategies is obvious. Despite the profound fears of the time, Western economies did not disappear into a black hole; growth has recovered, stock markets have prospered and, despite (largely German) hyper-inflationary fears at the time, inflation has remained contained. The banking system sits on a much firmer capital footing, with ample liquidity, lower leverage, and balanced sources of funding. So far, so good. Policy implementation of this magnitude, however, inevitably has consequences on a wider basis.

With this in mind we must ask whether it is likely that the current patterns hold. Is it likely that the policy regime that has been in place since the GFC remains the same moving forwards? There is certainly the chance that this could continue to be the case near term, but we are increasingly of the view that it is unsustainable over any meaningful period of time; no politician could now be elected on a platform of austerity. Populism is a genie that is not easily put back in a bottle.

Alan Schwartz, Guggenheim PartnersThroughout centuries what we’ve seen when the masses think the elites have too much, one of two things happen: legislation to redistribute the wealth…or revolution to redistribute poverty.

Invesco Solutions develops capital market assumptions (CMAs) that provide long-term estimates for the behaviour of major asset classes globally.

In our monthly market roundup for February, Invesco experts give a rundown of a mixed month for global equity markets, as well as an update on fixed income markets.

After years of low inflation, the coronavirus pandemic has created a perfect storm of inflationary pressure as government stimulus packages, supply bottlenecks, the economic recovery and pent-up spending all contribute to rising prices.