What are the implications of China’s carbon emissions trading scheme?

What is the scheme about?

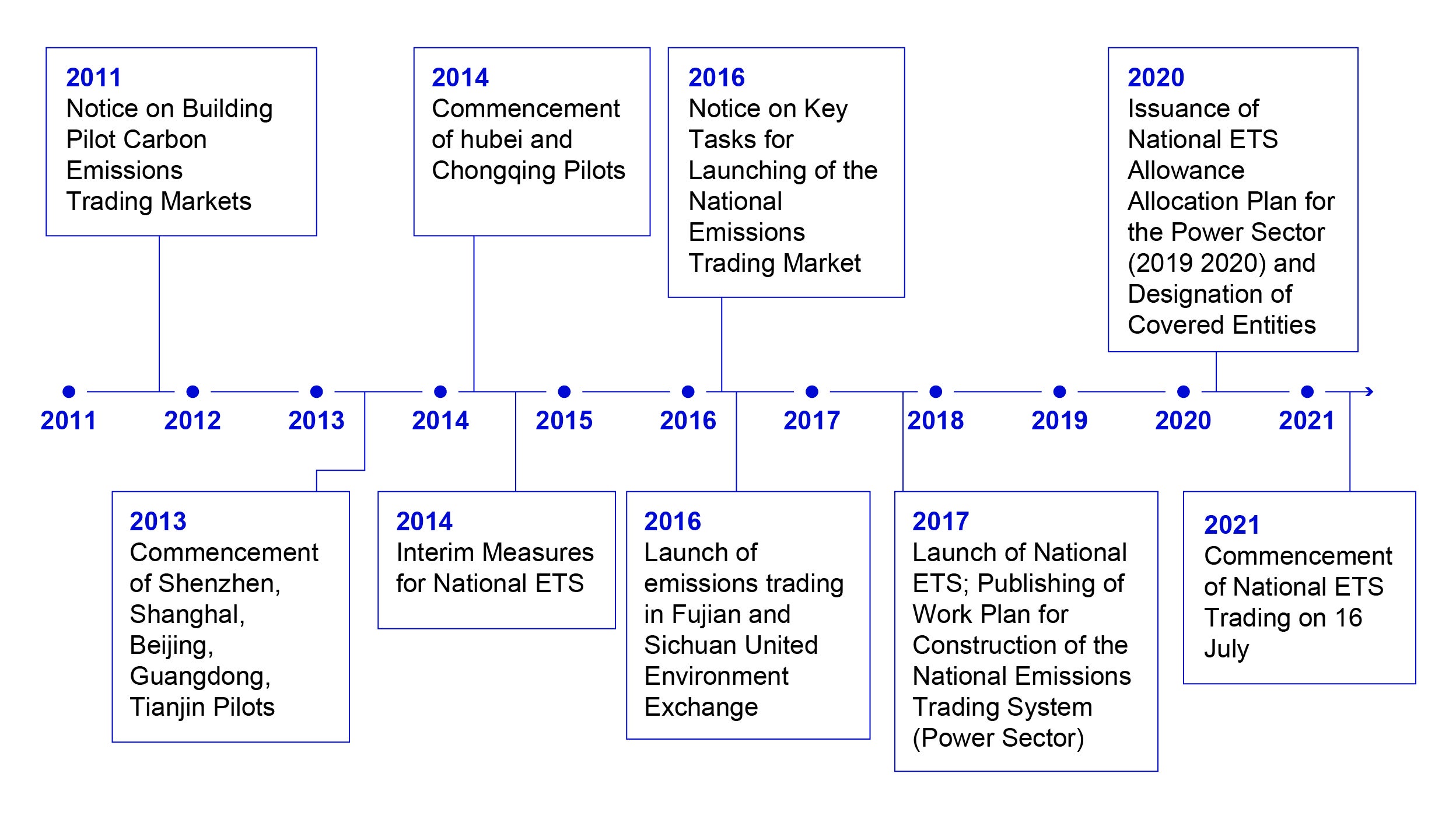

China’s national carbon emissions trading scheme (ETS) was launched by the Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE) in mid-July and is the world’s largest carbon market by volume.1 Managed by the Shanghai Environment and Energy Exchange, it brings together eight municipal and provincial pilot schemes2 that have been in effect since 2013(see Chart 1).

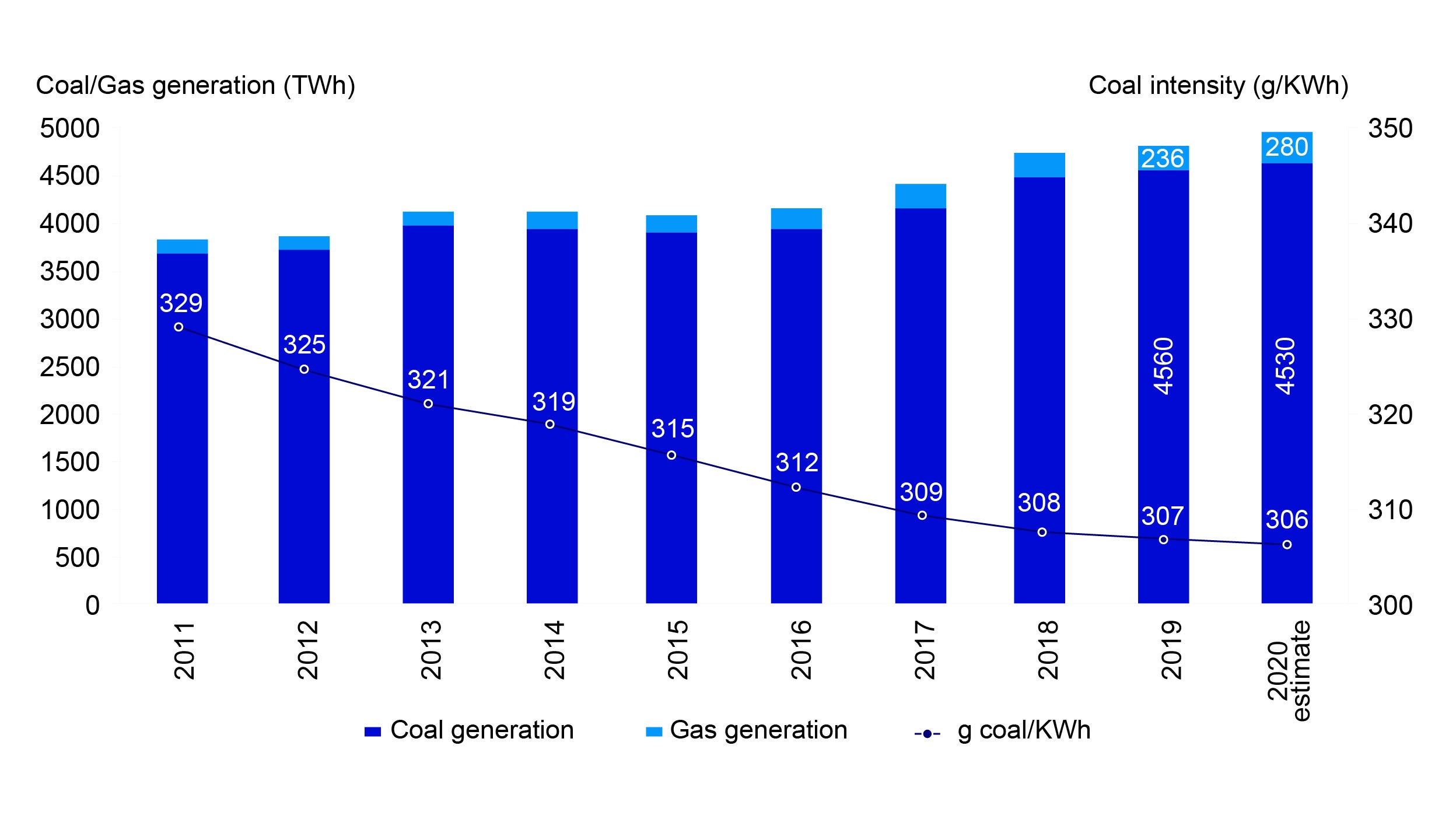

The first phase of the ETS covers 2,225 coal- and gas-fired power plants accounting for about 40% of national emissions. Participating companies are allocated a certain number of free emissions permits up to a set cap (a function of historical power and heat output, government-determined emission intensity benchmarks, and other adjustment factors).3 They can then either buy or sell allowances if their emissions remain below or exceed this cap.

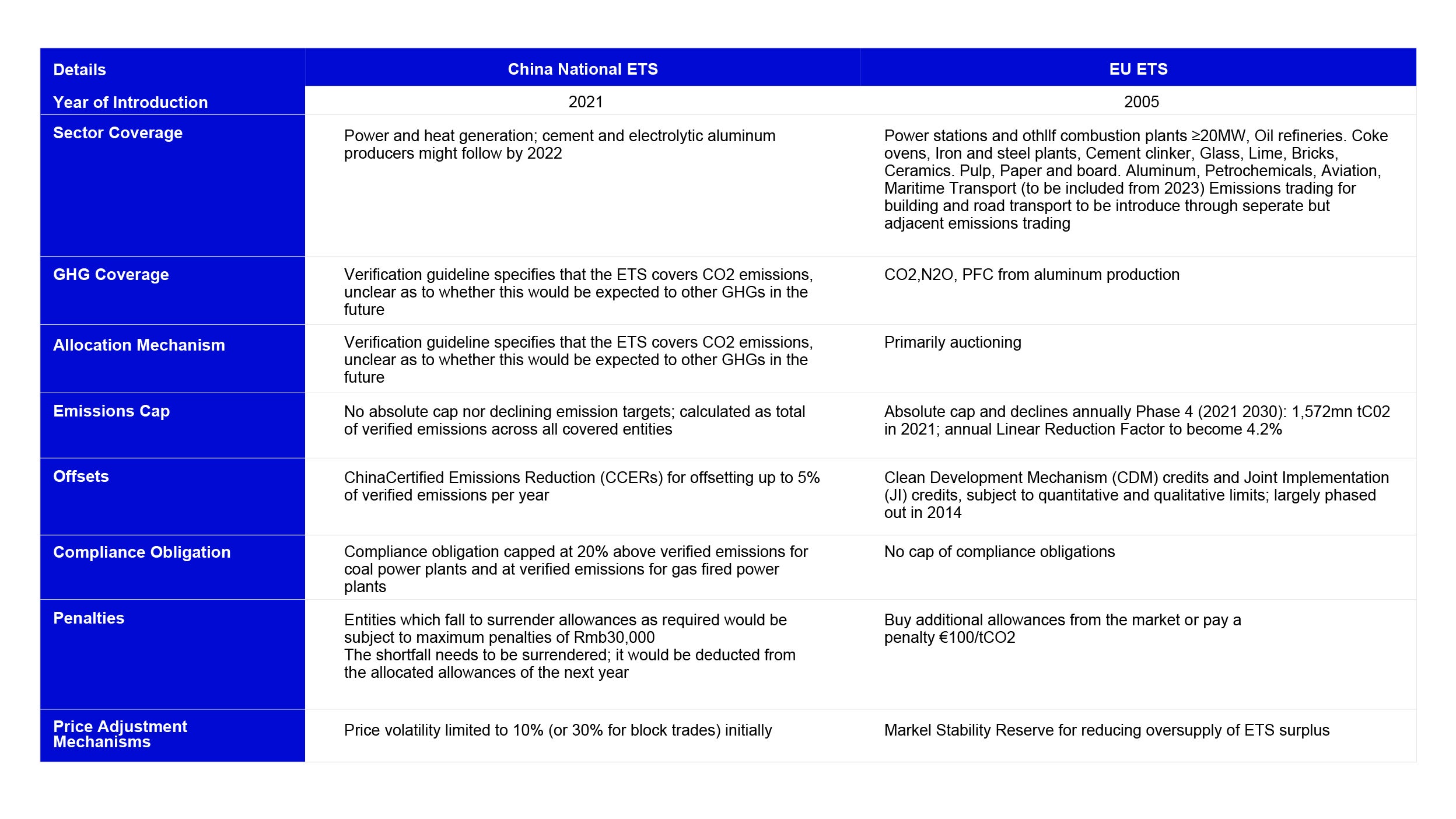

Unlike the European Union’s Emissions Trading System (EU ETS), the allocation of permits in China’s ETS will be based on “carbon intensity” (see comparison in Table 1). This looks at the amount of emissions per unit of power generated rather than an absolute level of emissions.4 Some critics argue this may reduce the effectiveness of the scheme as absolute emissions can still increase as energy output increases. On the other hand, this model can ease concerns over constraints on economic growth that could result from reduced power consumption.

In the future, the ETS is expected to expand to cover other sectors aside from power, including petrochemicals, chemicals, building materials, steel, nonferrous metals, paper, and domestic aviation.5 The way in which the government will choose to allocate carbon emissions quotas for other industries is still unknown.

China’s Metallurgical Industry Planning and Research Institute (MPI) is currently working on several issues related to incorporating the steel industry into the ETS. To better understand the challenges domestic steel mills are facing and appeals they have, the MPI is soliciting opinions and suggestions in areas such as quota assignment, working mechanism testing, market inspection, and low-carbon standard system set-up.6

What is the expected impact?

We expect the short-term impact of the ETS to be quite limited as the aim is to enable a smooth transition from the earlier pilot schemes. The government needs to incentivize companies to reduce their carbon footprint without hurting the competitiveness of the overall industry or disrupting economic activities. As a result, we foresee that carbon prices will be low in the short run as compared to other schemes globally. However, it is worth noting that even when the EU ETS started in 2005, it faced teething issues. Emitters were encouraged to inflate their emissions due to a lack of reliable baseline data and carbon prices remained below expected levels (see Chart 2).7 The EU ETS is now widely regarded as a success and has resulted in a 3.8% reduction in total EU-wide emissions over the period between 2008 and 2016.8

In the long-term we believe China’s ETS will end up looking more like the present-day EU ETS in that if a company does not reduce their carbon emissions, they may end up being heavily penalized. We believe big market leaders will be the biggest beneficiaries of the scheme at the outset, given that they have the resources and scale to comply, while smaller companies might have more difficulty meeting the carbon intensity benchmarks.

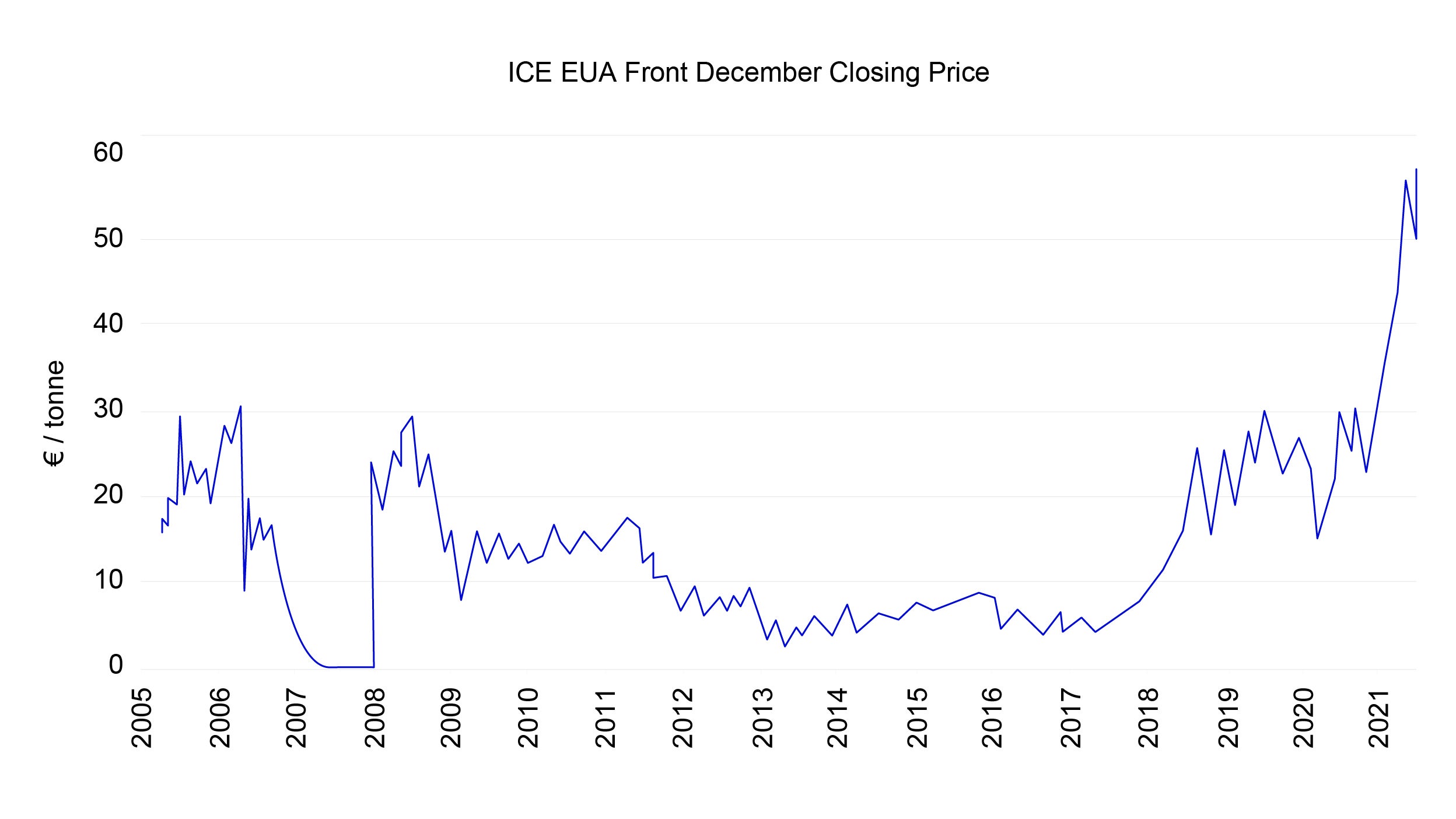

Historically, coal has played a key role in China’s energy mix and accounts for about 60% of electricity generation.9 In the past decade, the emissions intensity of China’s coal fleet has been declining as larger and more efficient coal-fired plants have replaced smaller older ones (see Chart 3). The Chinese government has also expanded the role of natural gas in different sectors. In 2021, major Chinese power generation companies announced plans to achieve peak carbon emissions by 2025 and to invest in renewables in a big way.

We believe that the ETS can help to phase out inefficient power generation sources using the approach of average carbon intensity as a metric. With its output-based allowance allocation design, the ETS will prompt more efficient coal-fired power generation. Units that achieve emissions intensities below the applicable benchmark can sell surplus allowances while those exceeding the benchmark would need to purchase them.10 We expect this can lead to an improvement in carbon intensity emissions among power plants in the short term. However, with the long-term aim to achieve carbon neutrality, China’s ETS needs to offer greater incentives for power plants to switch from coal to renewable energy sources.

The steel, cement, and aluminum sectors are responsible for the highest carbon emissions in China, accounting for 18%, 16% and 5% of total emissions, respectively. Large production cuts have already been announced for steel and aluminum that could cut 1-5% of production by FY21E.11 The advent of the ETS could further tighten supply. One major impact of carbon trading across different materials, including steel, cement, and aluminum, will be steeper cost curves and supply cuts. Thus, more efficient producers will likely benefit. Given the higher carbon expenses for emissions exceeding the free quota, producers that emit more will likely move to the higher end of cost curves.12 Regarding supply cuts, we expect such producers (whose actual carbon emissions exceed the allocated free quota), to face frequent supply disruptions as they aim to control their overall emissions.

What could hinder the scheme’s development?

China’s ETS currently has a flexible emissions cap that can fluctuate depending on the output and intensity benchmark of the power plant in question. This gives plants the incentive to outperform their benchmark by running more efficiently. However, these allowances can be adjusted and can also include a bonus for sites that operate infrequently, which could counter this efficiency incentive.13

In the current design, power generation companies in aggregate are still expected to be allowed to emit more than 4 billion tons of greenhouse gases in 2021. However, many expect the government to gradually tighten the quota in the coming years, and auction an increasing proportion of it, shifting away from the current approach of giving it away for free.14

From perspective of regulators, the challenge will be to balance incentivizing companies to adhere to the ETS while also ensuring they do not face too much of a financial burden. One major criticism of the scheme at present is the limited penalty for non-compliance or forged information at just 30,000 yuan.15 Companies will need allocate resources to change their business model and operating style to meet the new requirements. Affected companies may then compare the cost of compliance relative to paying the penalty.

Another challenge is the potential reputational risk companies may face by purchasing carbon allowances on the exchange. Stakeholders may view this as a signal that the firm’s climate performance is below average, particularly given the more stringent ESG disclosure rules for publicly traded companies in recent months.16

What are the investment implications?

Despite some potential bumps along the road, we believe that the scheme is a step in the right direction. In our opinion it will be positive for international and domestic investors in the long-term as it provides a financial measure on national carbon emissions and rewards corporates for their efforts in carbon reduction. This is expected to enhance transparency as investors will be better able to quantify what the government and specific companies are doing to help China meet its sustainability targets. Large asset owners in developed markets such as the US and Europe are using carbon pricing to assess the true cost of carbon abatement. In the same way investors can use China’s carbon pricing data to further assess how companies’ capital expenditure is being spent toward climate change mitigation.