Thinking thematically: Water, water everywhere – and not a drop to drink

Overview

With growing demand and falling supply, the water system remains under threat

Water technology could play a role in improving our efficiency and preserving the supply we have

Water ‘moonshots’ may be the next step, however, to combating supply challenges

In many ways, water is a victim of its own success. Since the 1850s, the global water system has only gotten better. Gone are the days of sewage filling the streets, of mass cholera outbreaks and the Great Stink of London. Starting with the London Metropolis Water Act of 1852, requiring the filtration of all public water, we finally began to claw back a millennia of backsliding, attempting to return to the days of the Roman aqueduct1.

In many ways, we succeeded. In much of the developed world, you can turn on any tap and safely drink the water. In the US, the water network runs 2.2 million miles (3.5 million kilometers)2, which is nothing compared to Europe, with 1.9 million kilometers (1.2 million miles) between France, Germany, and Italy alone3. Unfortunately, that ease has made water an abstraction for many, like electricity, something we use without thinking – and we’re using it far too quickly.

Water demand is up 40% over the last four decades while the supply has halved4. Water use is the common thread in everything we do, with 70% going to agriculture and 19% to industry5. Even our most cutting-edge technologies require water, with semiconductors requiring ultra-purified water and Chat-GPT gulping a liter to cool its servers every 40 commands4.

Given its vital importance, water is one of the spaces we follow most closely. Today, we’ll take you through where we are, where we’re headed, and some of the technologies that could help us get there.

The state of water supply

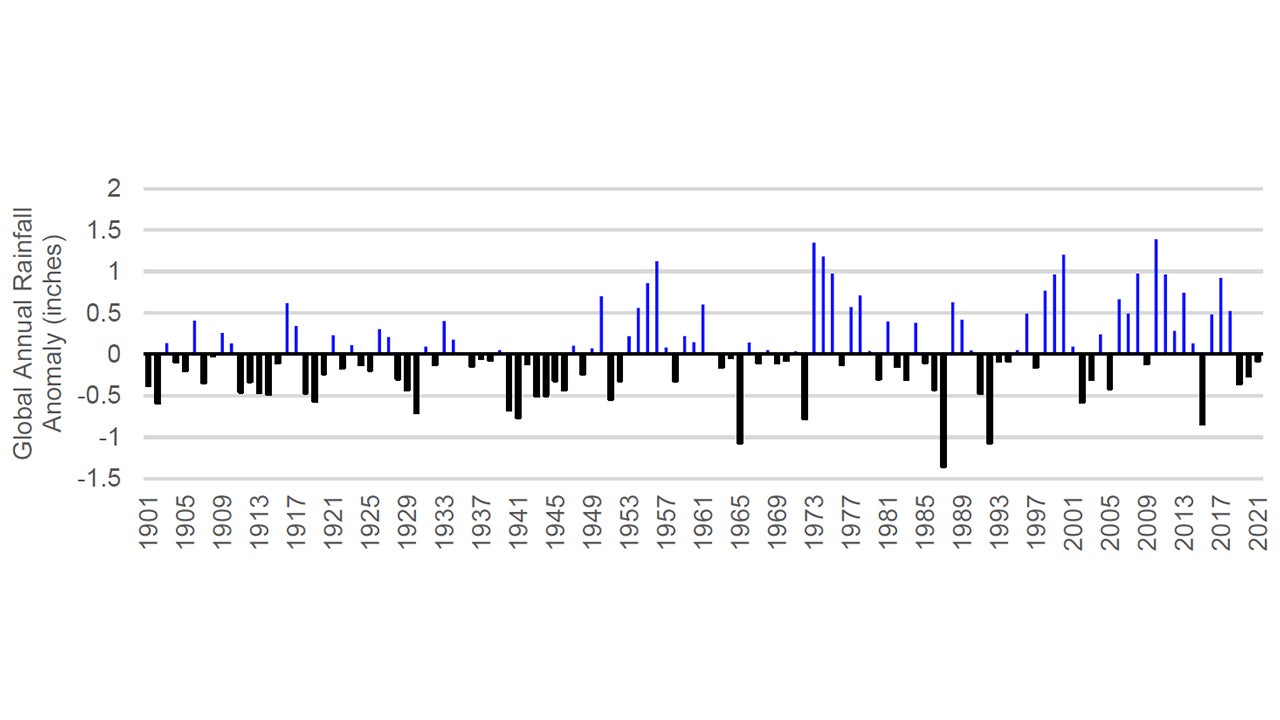

The global water system is facing many threats. Chief among them, of course, is climate change. We’ve just lived through the hottest 12 months in 125,000 years of geologic history, and its mark on the water system – through drought on one end and flooding on the other – is all too clear6. In Europe, the summer of 2022 saw unprecedented drought along the Danube, with water levels falling far enough to reveal shipwrecks and ammunition from World War II7. Asia has seen similar challenges, with powerful droughts in China causing blackouts in 2022 from dried up hydroelectric dams, while heavy monsoon rains in India in 2023 hit agriculture and food prices8.

That’s not the only problem, either. Of the vanishingly small amount of fresh water – less than 1% of our water is usable despite 75% of the planet being covered in it4 – growing amounts are also threatened by pollution, with 90% of groundwater in China, for example, deemed contaminated9.

The vast infrastructure we’ve built out for water supply also needs work. Aging pipes lose 1/3 of all water to leakage4, while those same pipes often pose the risk of lead contamination. In the US, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) recently passed more stringent rules on lead safety. This could actually be a boon to major utilities, who already have aggressive capital spending plans for lead and PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances known as ‘forever chemicals’)10. But as they scoop up more municipal water projects that lack the capacity to spend on such issues, the landscape is clearly changing 10.

The role of water technology

While pipes and utilities are still the backbone of water investing, the theme is also much broader than those traditional industries alone. Water technology can alter the way we use the water we have, seeking efficiencies in our systems and the purification of the water we currently have.

Within our current water infrastructure, this can look like better utilization of water data with smart meters and leak detectors, providing ‘system visibility’ that can improve response times and reduce waste11. In agriculture, there are myriad ‘water sense’ technologies like soil moisture sensors, targeted irrigation, drones, and even artificial intelligence solutions that could save up to 20% of current irrigation levels12.

Within waste prevention and decontamination, there has been interest in nanotechnology and the use of nanostructured material to remove pollutants like arsenic from the water supply13. In medicine, water pressure tools are being used in surgery, while water quality and testing remain important fields to ensure precision and purity14.

Water moonshots?

Beyond our current technology, there is also growing interest in ‘moonshots’ – ambitious projects with new technologies – to start a new age for the water industry. One very science-fiction example is asteroid mining, whereby scientists could extract the ample water on space objects – and maybe even use it on a future Mars colony4. Other attempts, however, are more homegrown. Technologies to harvest dew, fog, and even air humidity using solar energy are all possibilities, though we’ll need time to test and scale these solutions15. Desalination is another area ripe for disruption where current energy intensive technologies have made the technology difficult to scale despite an abundance of seawater on our planet16.

What happens next?

Despite facing plenty of uncertainty in the world of water, one thing is clear – we need to become more ambitious about our water system. The future will need technologies both new and old ranging from pipes and pumps to more farfetched moonshots to boost supply. Water will always be essential to human life, and that’s why the scale of the problem requires the best of human innovation. It’s been nearly 130 years since we first began chlorinating our water, and I hope the next 130 see us sipping water on the moon.