A factor-based approach to diversifying oil exposure

Key takeaways

Institutional investors who are highly sensitive to oil price changes are keen to reduce their risk exposure without explicitly engaging in oil price hedging.

We investigate a viable alternative that considers diversifying oil exposure by employing adequate market and style factors.

In particular, we present a multi-asset multi-factor solution in which quality and low volatility style factors play a crucial role in mitigating oil risk exposure while increasing overall portfolio diversification.

The idea of a country establishing an investment portfolio with the proceeds of a temporary revenue stream is nothing new. It is the model used by many sovereign asset managers around the world, such as those of Norway and the Gulf economies. In such economies, the revenue stream from extraction of natural resources (notably, oil and gas) is not expected to be permanent, so the intention is to build up a fund for when the resource revenue declines and, eventually, dries up. In Norway, for example, around half of oil reserves have been extracted over the last fifty years and, if extraction continues at the same pace, the reserves are expected to last only another fifty years.1 There are, however, different ways in which the accumulated assets can be used by sovereign asset managers.

Sovereign asset managers can be seen as falling into one of five broad categories:2 investment sovereigns (which do not have liabilities), liability sovereigns (which have liabilities either currently or in the future), liquidity sovereigns (normally commodity exporters which seek to manage assets to stimulate their economies during a commodity downturn), development sovereigns (which seek to drive local economic growth) and central banks (which have historically concentrated on the management of foreign exchange reserves but have taken on a greater role as sovereign asset managers in recent years).

The Norwegian sovereign wealth fund, for example, is currently both a liability sovereign (as it has future liabilities) and a liquidity sovereign (as short-term economic management is its secondary goal). In the early days of oil and gas extraction, however, the proceeds were used primarily to develop the economy: it was a development sovereign. In 1996, the Norwegian oil fund was established. On behalf of the Ministry of Finance, the fund is managed by Norges Bank (Norway’s central bank), and it is now one of the largest sovereign wealth funds in the world, owning around 1% (by value) of listed global equities.

Diversifying oil with style

One important issue facing an oil (or other resource)- rich economy is that global economic growth and inflation, and hence developments in asset prices, are often closely correlated with the oil price. As a case in point, two recent oil shocks, both of which saw oil prices fall by 76%, have been accompanied by sharp falls in equity markets: in the second half of 2008, the peak-to-trough decline in oil prices was from USD 145.6 to USD 34.6, representing a -76% change. At the same time, the MSCI World index lost 34% of its value and the nominal yield of US 10-year Treasuries shrank by 175 bps to 2.19%. The second major oil price collapse lasted from 19 June 2014 to 20 January 2016 with another -76% change (from USD 115.5 to USD 27.8). Over that period, the MSCI World index fell 14% and US 10-year nominal yields declined by 54 bps. This raises a concern that achieving diversification of oil exposure by investing in market factors such as equity and credit may be far from optimal. Of course, government bond investments are a natural candidate to diversify all of the above asset classes. Yet their associated absolute return proposition is weaker given the prevailing low yield environment.

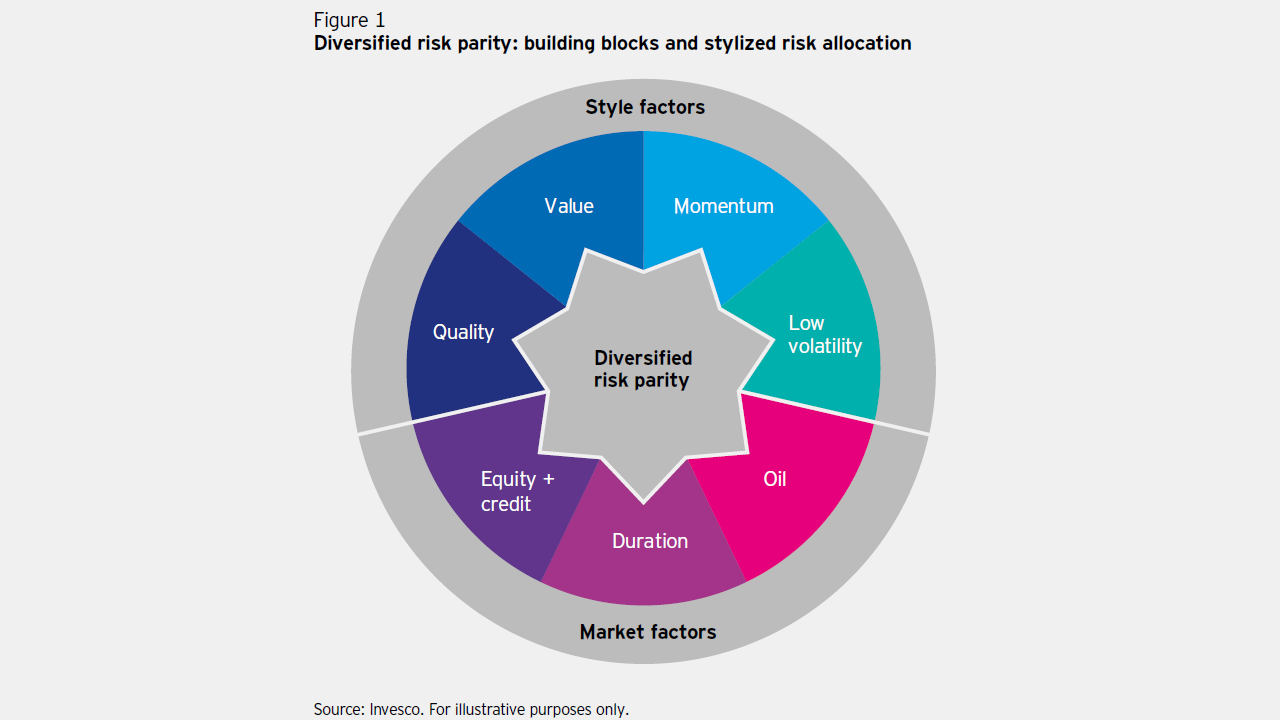

To thoroughly address the question of diversifying exposure to oil, one needs to combine major sources of risk and return that permeate capital markets and determine the pricing of assets. In this vein, market factors related to equity and credit, duration or commodity risk are obvious contributors to any global multi-asset risk model. In complementing this set of factors, the literature has put forward the notion of style factors that help explain the crosssection of many asset classes. Figure 1 features four equity style factors, including quality, value, momentum and low volatility. By design, these style factors invest according to firm characteristics that are ultimately associated with distinct return patterns. All considered, style factors are long-short factors and thus do not carry significant equity market risk.

For instance, value investing looks to buy relatively cheap securities while selling more expensive ones, often leading to a pro-cyclical return profile. Conversely, momentum investing rests on the observation that past price trends tend to continue. Consequently, momentum strategies are far more active when seeking to capitalize the price differential between winner and loser stocks. Given the return profiles of these two salient style factors (value and momentum), one may ask which other factors could act as more natural diversifiers with respect to significant equity or commodity risk exposure. In this regard, quality investing looks to invest in companies that excel in terms of a number of metrics associated with high balance sheet quality. A related, yet distinct, route is to directly enforce a defensive low risk profile by focusing on low volatility names. Additionally, shorting the broad market then allows capitalizing the low volatility effect, which relates to the empirical evidence of risk-adjusted outperformance of low volatility companies. Both defensive style factors, quality and low volatility, tend to be particularly strong when broad equity markets suffer.

Oil allocation through the factor lens

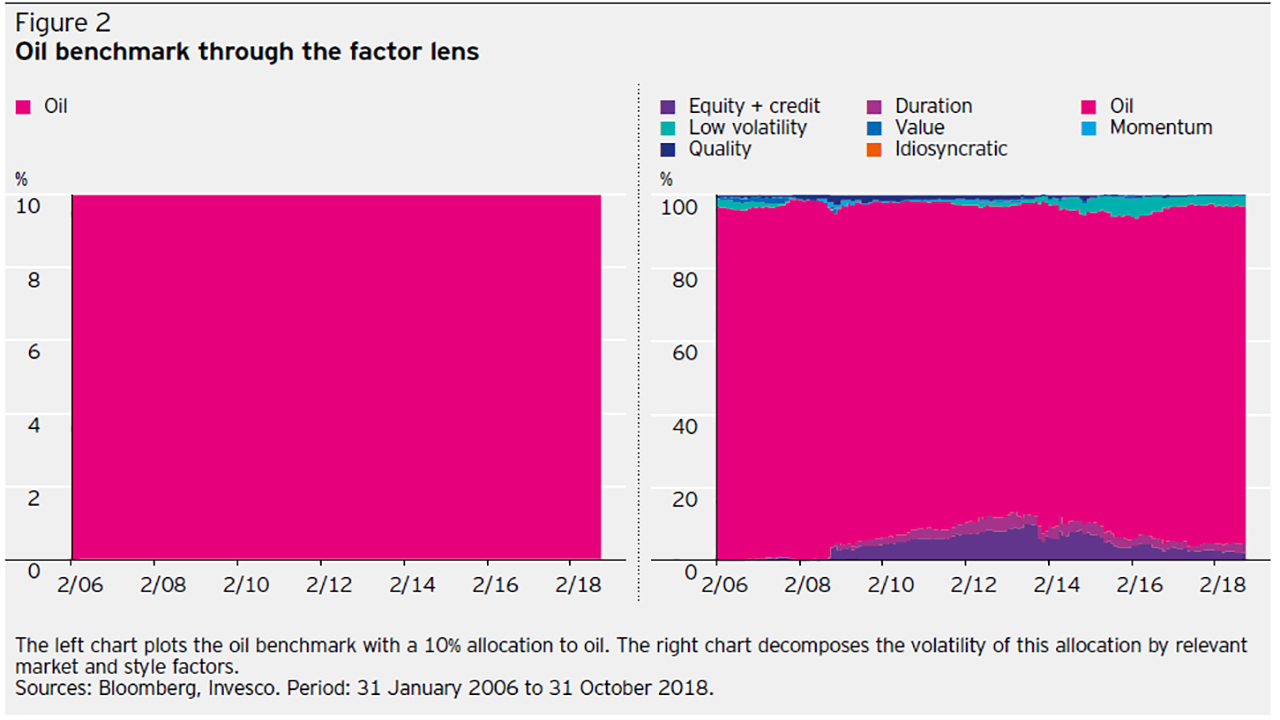

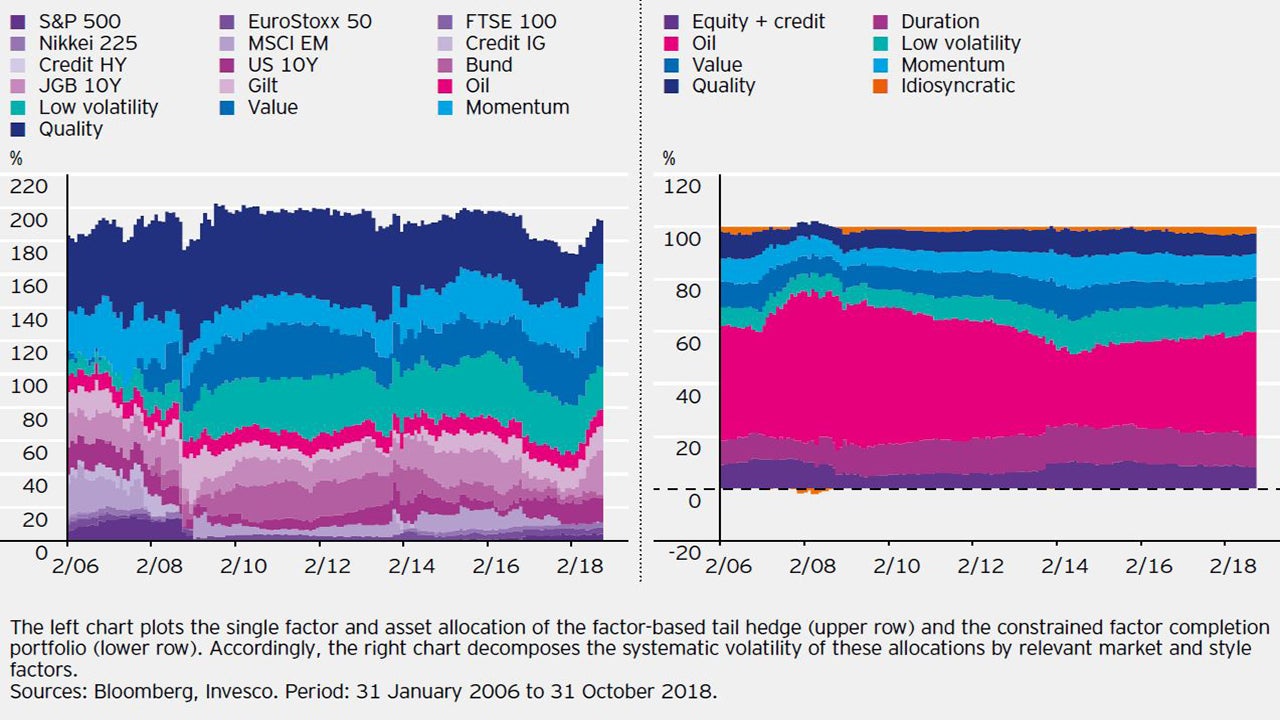

To investigate the extent to which oil exposure can be diversified by means of additional multi-asset and multi-factor exposures, we consider a simple benchmark with a constant allocation of 10% in oil,3 referred to as the ‘oil benchmark’. For simplicity, we assume the remainder of the oil benchmark allocation to be invested in cash (as proxied by 3-month US Treasury bills). In evaluating the benchmark’s risk exposure, we follow Dichtl, Drobetz, Lohre and Rother (2019) in building a risk model consisting of three market factors (equity, duration and oil risk) and four equity style factors (value, momentum, quality and low volatility), as shown in figure 1. Based on these seven factors, we x-ray and explain the oil benchmark’s portfolio risk.4

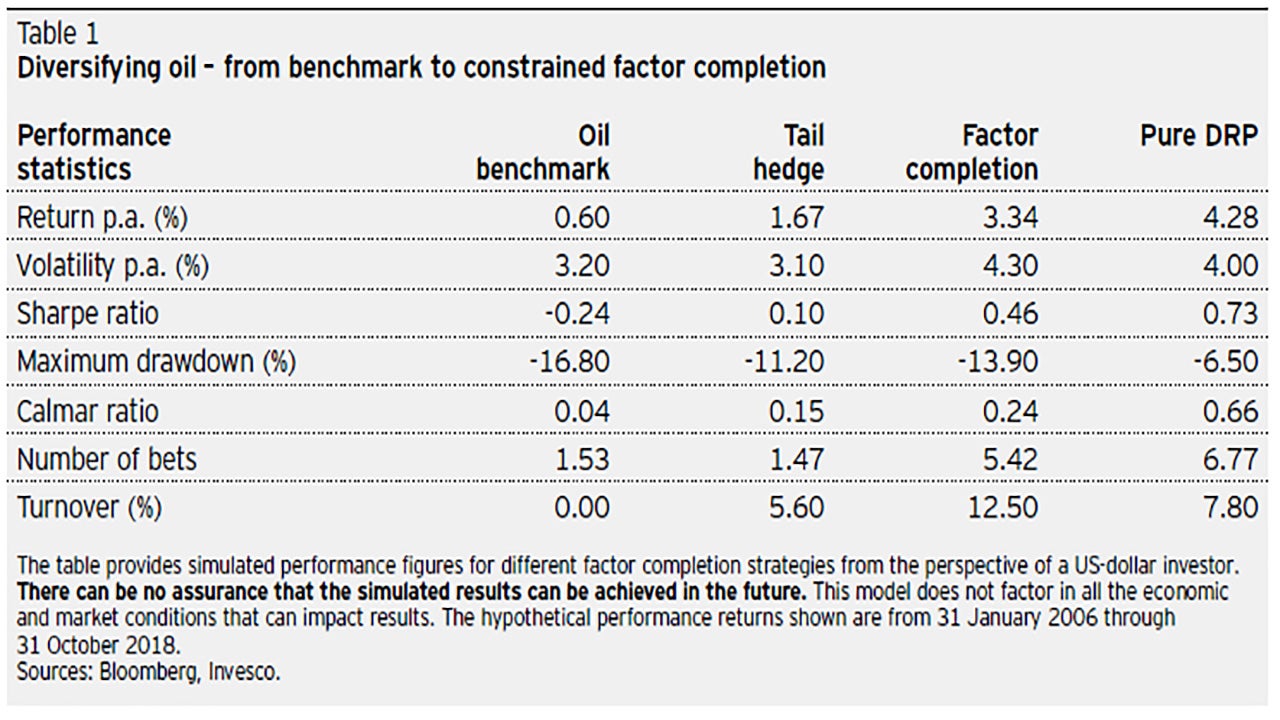

Unsurprisingly, we find more than 80% of portfolio risk to be related to commodity or oil-specific risk (figure 2). Even so, we note that the oil benchmark also carries some equity and duration sensitivity throughout time. Moreover, there are even some style factor exposures to be observed. Given the negative performance of oil investments in the sample period, the 10% oil allocation leads to an overall return of the oil benchmark of 0.59% p.a. at an annualized volatility of 3.2%, thus underperforming the risk-free rate. Despite the low volatility of the oil benchmark, one would have experienced a maximum loss of 16.8%.

Factor completion for oil benchmarks

In light of the above evidence, we examine whether one can alleviate the inherent downside risk of the oil allocation. Better diversification, in our view, can be achieved by combining exposure to equity style factors (value, momentum, quality and low volatility) with the above market factors. Dichtl et al. (2019) suggest different alternatives to tapping the diversification potential of style factors in an integrated portfolio optimization framework, including:

- Factor-based tail hedging: adding style factor exposure in the pursuit of better risk management, particularly minimizing portfolio volatility

- (Constrained) factor completion: using style factors to complete the risk allocation towards a fully diversified proposition while abiding by the benchmark constraints (i.e. holding the fixed 10% oil allocation)

In what follows, we utilize both approaches to diversification of the oil benchmark and shed light on the mechanics and nature of the ensuing portfolio allocation over time.

Tail hedging through equity style factors

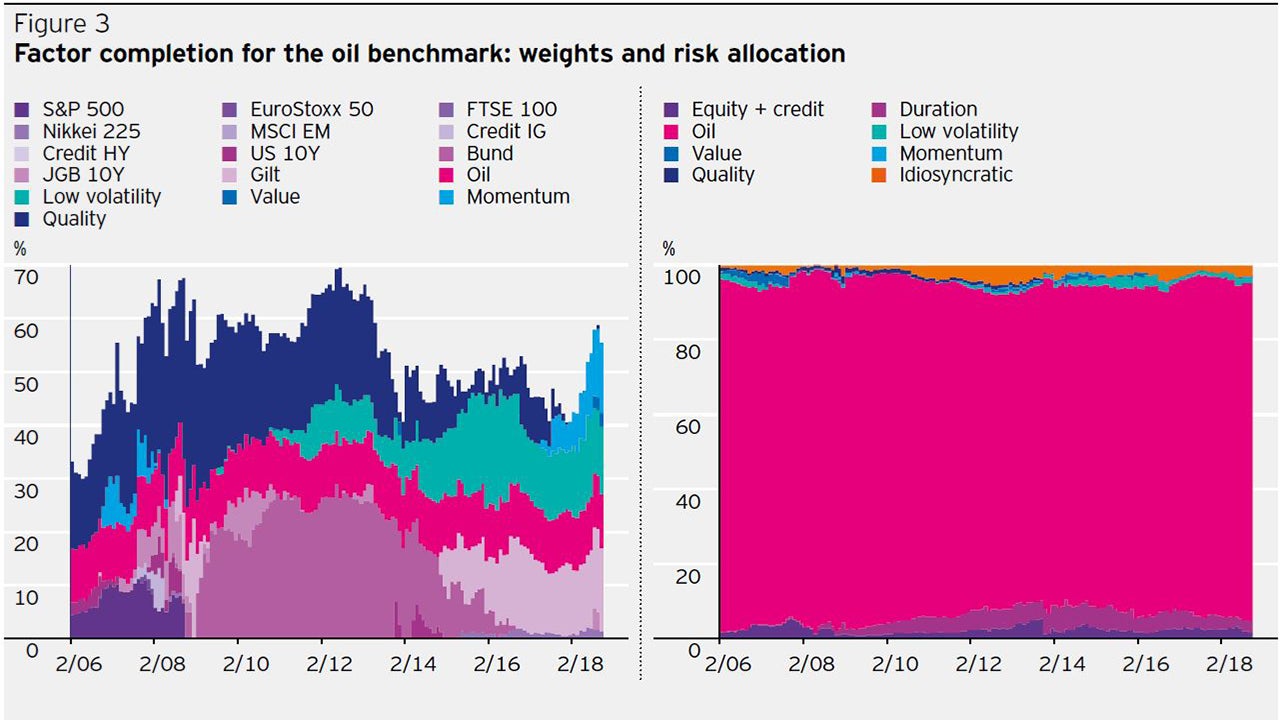

A major concern of holding the oil benchmark is the associated (tail) risk. Setting aside the upside potential of style factors, one may focus on their potential to minimize the volatility of the oil benchmark. Specifically, we run a minimum-variance portfolio allocation that is constrained to hold the oil benchmark but can dynamically add a factor completion portfolio to help reduce portfolio volatility. The resulting factor completion allocation is shown in figure 3.

As expected, the factor completion portfolio hardly considers exposure to broad equity markets for hedging purposes given that these are prone to similar growth shocks as oil. We instead observe a decent allocation to government bonds that is complemented by investments in equity quality and equity low volatility. As expected, these defensive styles help counteract the oil exposure. Notably, the reduction in portfolio volatility is marginal, going from 3.2% for the oil benchmark to 3.1% for the tail- hedged portfolio. The benefits of the factorbased tail hedge are more apparent, however, when looking at the reduction in maximum drawdown by 5.5 percentage points down to -11.2%. In all, the tail-hedged portfolio experiences an increase in performance to 1.67% annualized return, corresponding to a Sharpe ratio of 0.10.

Constrained factor completion

The factor completion solutions of Dichtl et al. (2019) are centered around the notion of a diversified risk parity (DRP) anchor to complete the oil benchmark. At its heart, this allocation paradigm seeks to maximize diversification for a given set of assets and factors. It turns out that maximum diversification prevails when running a risk parity strategy using de- correlated variants of the three market and four style factors.5

Unlike the risk allocation of the oil benchmark, which is driven primarily by a single factor, the optimal diversified risk parity portfolio would, by design, exhibit equal risk contributions for all seven factors. While such a pure factor completion might not always be attainable, we are particularly interested in the extent to which a constrained factor completion can drive out the substantial oil exposure of the benchmark allocation.

As expected, the factor completion portfolio hardly considers exposure to broad equity markets for hedging purposes given that these are prone to similar growth shocks as oil. We instead observe a decent allocation to government bonds that is complemented by investments in equity quality and equity low volatility. As expected, these defensive styles help counteract the oil exposure. Notably, the reduction in portfolio volatility is marginal, going from 3.2% for the oil benchmark to 3.1% for the tail- hedged portfolio. The benefits of the factorbased tail hedge are more apparent, however, when looking at the reduction in maximum drawdown by 5.5 percentage points down to -11.2%. In all, the tail-hedged portfolio experiences an increase in performance to 1.67% annualized return, corresponding to a Sharpe ratio of 0.10.

Constrained factor completion

The factor completion solutions of Dichtl et al. (2019) are centered around the notion of a diversified risk parity (DRP) anchor to complete the oil benchmark. At its heart, this allocation paradigm seeks to maximize diversification for a given set of assets and factors. It turns out that maximum diversification prevails when running a risk parity strategy using de- correlated variants of the three market and four style factors.5

Unlike the risk allocation of the oil benchmark, which is driven primarily by a single factor, the optimal diversified risk parity portfolio would, by design, exhibit equal risk contributions for all seven factors. While such a pure factor completion might not always be attainable, we are particularly interested in the extent to which a constrained factor completion can drive out the substantial oil exposure of the benchmark allocation.

Appendix

Here, we briefly describe the single asset and style factor indices underlying the article’s empirical analyses. The global equity and bond markets are represented by equity index futures for S&P 500, Nikkei 225, FTSE 100, EuroStoxx 50, MSCI Emerging Markets and bond index futures for 10- year US Treasuries, German Bunds, 10-year JGBs and Gilts. The credit risk premium is captured by the Bloomberg Barclays US Corporate Investment Grade (Credit IG) and High Yield (Credit HY) indices (both duration-hedged to synthesize pure credit risk). To capture the investment in oil, we consider the total return index of S&P GSCI for crude oil.

All equity style factors are constructed in a longshort fashion. We utilize the definitions as laid out in Investing in a multi-asset multi-factor world, Risk & Reward, #3/2017. In particular, value, momentum and quality each follow a multi-factor approach that combines several metrics proxying for the respective style dimension. For low volatility, we build on a long-short approach that is long a minimum-volatility portfolio while shorting a beta-adjusted market portfolio.

^1 https://www.nbim.no/en/the-fund/about-the-fund/

^2 According to the Invesco Global Sovereign Asset Management Study (2017).

^3 We believe this choice of benchmark to be representative of many oil-rich economies. In principle, the insights generated from this oil benchmark can be extrapolated for higher exposures to oil risk. Yet, there will be a natural upper limit to any factor-based diversification effort given the required leverage when approaching a 100% allocation to oil.

^4 To flesh out the risk exposures of the oil benchmark over time, we linearly map the returns R of the underlying 11 market assets and 4 style factors from the seven factors F: R = B’F, where B is a 7 × 15 matrix containing the factor sensitivities. In turn, the variancecovariance matrix Σ of returns R can be decomposed as: Σ = B’ΣFB + u, where ΣF is the global factor variance-covariance matrix and u captures the idiosyncratic variance.

^5 See Lohre, Opfer and Orszàg (2014) and Bernardi, Leippold and Lohre (2018) for operationalizing the concept of diversified risk parity across de-correlated (risk) factors, based either on principal portfolios or minimum torsion factors.

^6 The effective number of bets relates to the number of uncorrelated risk sources represented by a given allocation through time. Mathematically, it is computed as