Chinese onshore bonds: Understanding policy signals and market structure

Key Takeaways:

- Global index providers are increasingly including Chinese onshore bonds in their flagship indices. We provide insight into China’s onshore bond market and explain the key drivers and indicators that Invesco Fixed Income considers when investing in this asset class.

- Liquidity conditions top the list of important market indicators, in our view, due to their impact on interest rates and link to central bank policy.

- Similar to other global bond markets, repurchase agreement rates and bond yields are important market indicators, but we highlight several China-specific rates and policy signals that we believe are important in understanding China’s onshore market dynamics.

- We believe understanding market structure is important in determining investment positioning. We provide an overview of the major investors in the asset class and their historical investment preferences.

2019 marked a milestone for the Chinese onshore bond market. Two major index providers announced the inclusion of Chinese onshore bonds in their flagship indices and international investor interest reached historical highs in terms of bond holdings and trading volume.1

While global indices focus mainly on Chinese “rates bonds” (government and policy bank bonds), we believe they do not fully reflect China’s onshore bond universe. This report aims to help global investors understand the lesser known asset classes that comprise the Chinese onshore bond market, provide an overview of its general structure and explain the key macro and policy considerations that influence its dynamics.

Invesco Fixed Income Investment Process

As with Invesco Fixed Income’s approach to other global bond markets, we consider three key factors when investing in China’s onshore market: liquidity conditions, economic fundamentals, and market technicals. Variation in trading liquidity among different types of bonds and their tenors, changes in macro policies or new financial regulations, for example, may have profound effects on market fundamentals and technicals. Differing investor preferences for duration and credit risk may also influence market movements. Below, we outline the important indicators we monitor and how China’s policies have impacted China’s onshore market dynamics.

Key Market Indicators

Liquidity Conditions: We rank liquidity conditions at the top of the list of considerations when making investment decisions in China’s onshore bond market. This is not only because liquidity conditions are the starting point for gauging the overall level of interest rates, but because they provide information about the central bank’s (the People’s Bank of China (PBoC)) monetary stance. This signaling effect is particularly helpful when the PBoC embarks on policy changes.

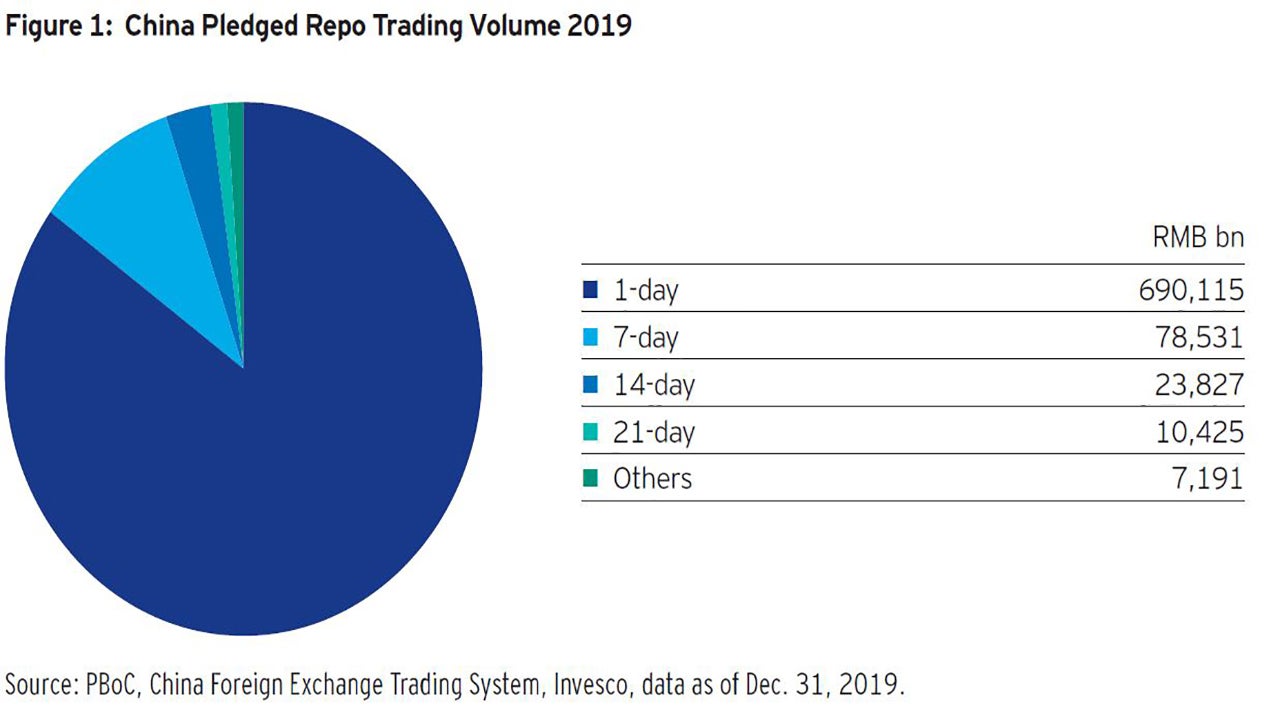

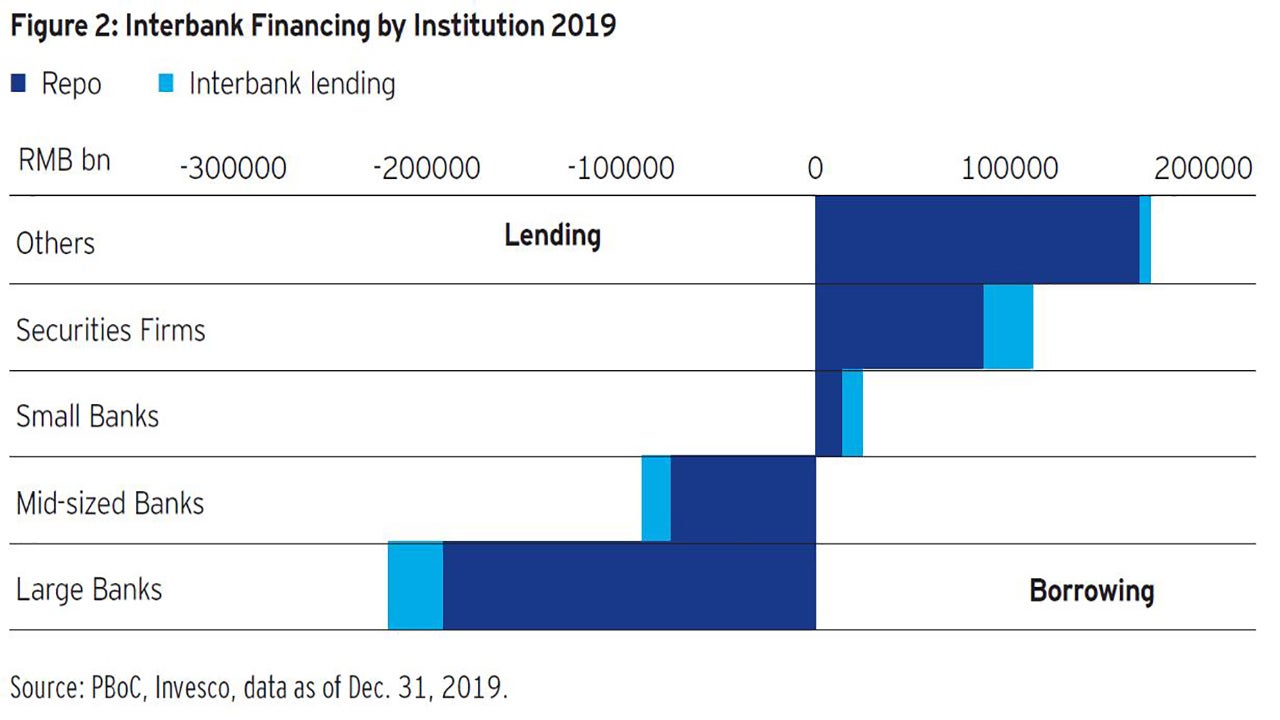

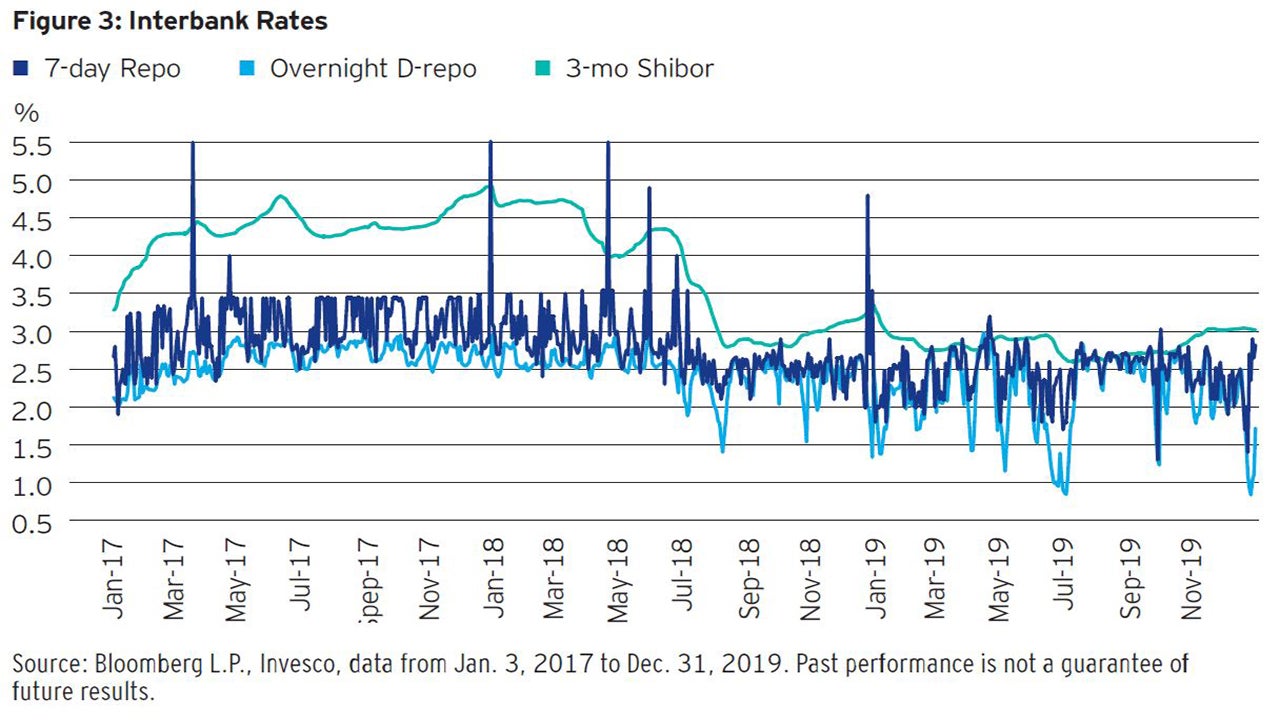

Repo Rates: Repurchase (repo) rates refer to interest rates on repurchase transactions in the interbank market in which bank and non-bank financial institutions participate. Most actively quoted rates include those on overnight, 7 and 14-day tenors. Overnight and 7-day repos account for the majority of repo transactions, with large banks as the main liquidity providers (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2). In the past, the PBoC and investors viewed the 7-day repo rate as the key market barometer, but this rate includes transactions by non-bank financial institutions and rates were often volatile and not necessarily reflective of overall levels of banking system liquidity. Currently, the volume-weighted overnight repo rate (D-repo rate) is viewed as a good indicator of interbank liquidity.

D-Repo Rates: D-repo rates refer to volume-weighted average rates of repo transactions between deposittaking institutions (such as policy and commercial banks). Rates bonds, including government bonds, PBoC bills and policy bank bonds are used as collateral. D-repo rates narrow the scope of participants and collateral, reducing the credit risk embedded in the calculated rates. D-repo rates are, therefore, seen as better reflections of banking system liquidity. Over time, the PBoC has shifted its focus among the key repo rates, and most recently the market views the overnight D-repo rate as a primary indicator of the PBoC’s monetary stance.

Shibor: The Shanghai Interbank Offered Rate is calculated based on unsecured interbank lending rates (overnight to one-year) offered by designated banks in the interbank market. The rate is calculated and announced on the platform of the National Interbank Funding Center in Shanghai. Although Shibor rates range from overnight to 1-year, 3-month Shibor is the most widely quoted rate.

Currently, 18 Chinese banks submit quotes on a daily basis. The published Shibor rate is the simple average after removing the four highest and four lowest quotes. As the quotes are submitted by only a few large banks in China, Shibor has been relatively less sensitive than repo rates, for example, to interbank liquidity changes (Fig. 3). Historically, 3-month Shibor has been used as a reference rate to price loans, however, it is expected to be replaced by the loan prime rate (LPR) going forward, which is based on the medium-term lending facility rate (described below).

Open Market Operations (OMO): OMO is a frequently used monetary policy tool to adjust interbank liquidity. The onshore bond market closely monitors the PBoC’s daily net injections or withdrawals of liquidity via OMOs (repos, reverse repos, and fiscal deposit auctions). Rate changes in repos or reverse repos send a strong signal to the market about how much the central bank intends to raise or lower banks’ funding costs and therefore interbank rates. This signaling effect can be even more significant when the PBoC changes policy direction, for example, from liquidity injection (reverse repo) to liquidity withdrawal (repo) and vice versa (Fig. 4). These shifts are usually considered to be early indicators of a changing monetary stance.

Medium-Term Lending Facility (MLF): The MLF is a lending facility provided by the PBoC using rates bonds and high-quality credit bonds as collateral. Tenors are relatively longer than OMOs, with 3-month, 6-month and 1-year MLFs having been conducted so far. The targeted MLF (TMLF) was introduced in December 2018 to promote financial institution lending to small and private companies. The TMLF tenor is one year, with options to be rolled over twice. The MLF has become more important with the implementation of recent lending rate reforms. The 1-year MLF is now widely considered to be the benchmark interest rate in China, as bank loans are now priced based on the loan prime rate, which is priced based on the MLF rate.

Interest Rate on Excess Reserves (IOER): The IOER is the interest rate paid to banks by the PBoC on banks’ excess reserves deposited at the central bank. Although this tool is rarely used, its impact has been significant, as reflected in the corresponding moves in money market and short-dated rates bonds. This is because the IOER is seen as the floor to repo rates. The most recent use of IOER was announced on April 3, 2020 when the PBoC halved the rate from 0.72% to 0.35%.2 This is the first change in the IOER since 2008.3 The 37 basis point cut led to a similar move in the yields of 1-year rates bonds in the onshore bond market.4

Required Reserve Ratio (RRR): The RRR is the percentage of deposits financial institutions are required to keep at the central bank. In recent years, the PBoC has implemented RRR cuts in a targeted manner to serve certain policy objectives. For example, there have been more favorable RRR cuts for certain types of financial institutions or banks that lend a certain amount to rural areas and small companies. Given the significant market impact of RRR moves, the PBoC usually uses this policy tool when it believes the economic environment requires a proactive and impactful monetary stance.

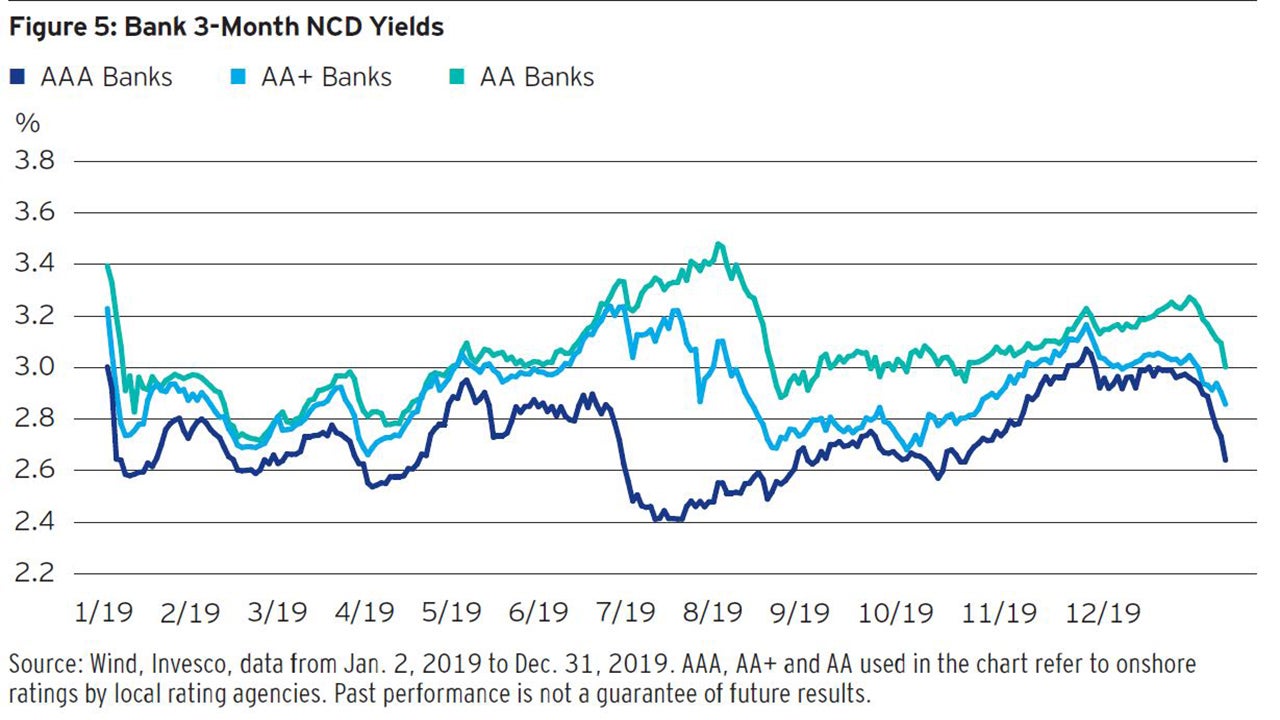

Negotiable Certificates of Deposit (NCDs): Negotiable certificates of deposit are issued by banks in the interbank market. The cost of issuance and general market demand for NCDs are seen as important reflections of individual banks’ short-term funding conditions. There have been periods when yields on NCDs of large and small banks have diverged due to changing policies, market conditions, seasonal effects and idiosyncratic events (Fig. 5). For example, in mid-2019, the takeover of a small city commercial bank by the PBoC led to a flight to safety which reduced large banks’ funding costs but led to a spike in other smaller banks’ NCD rates.

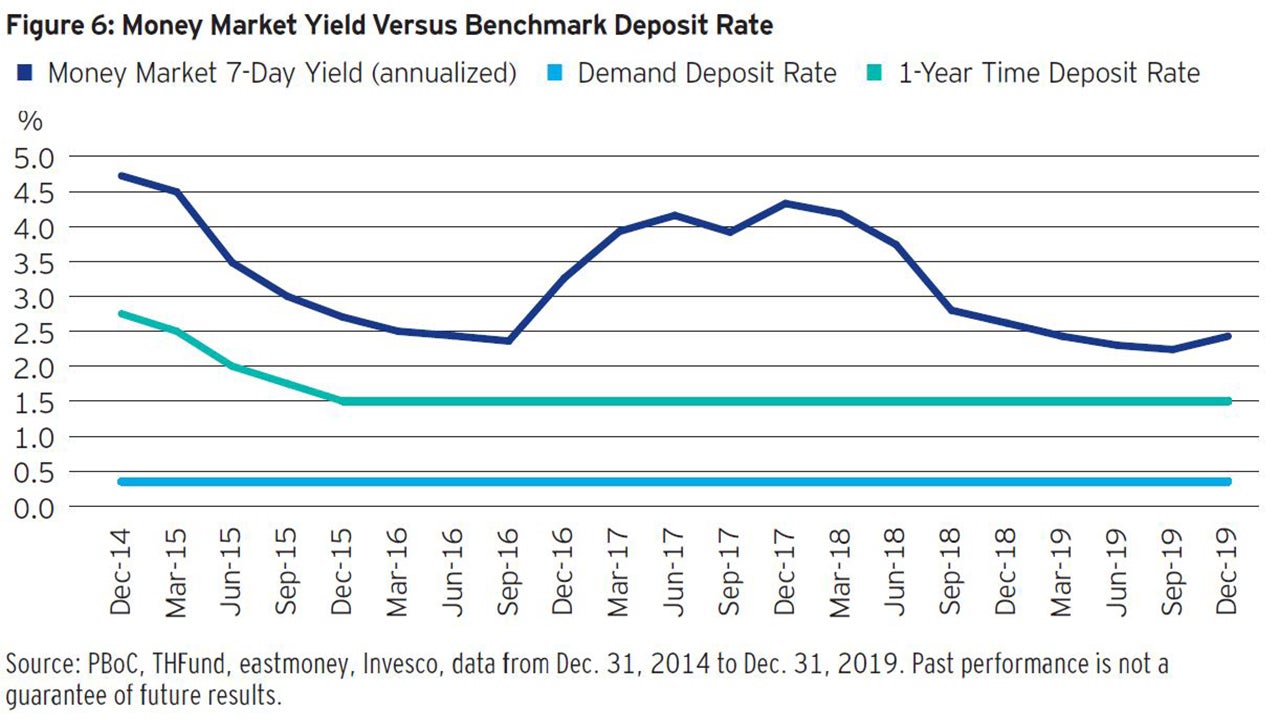

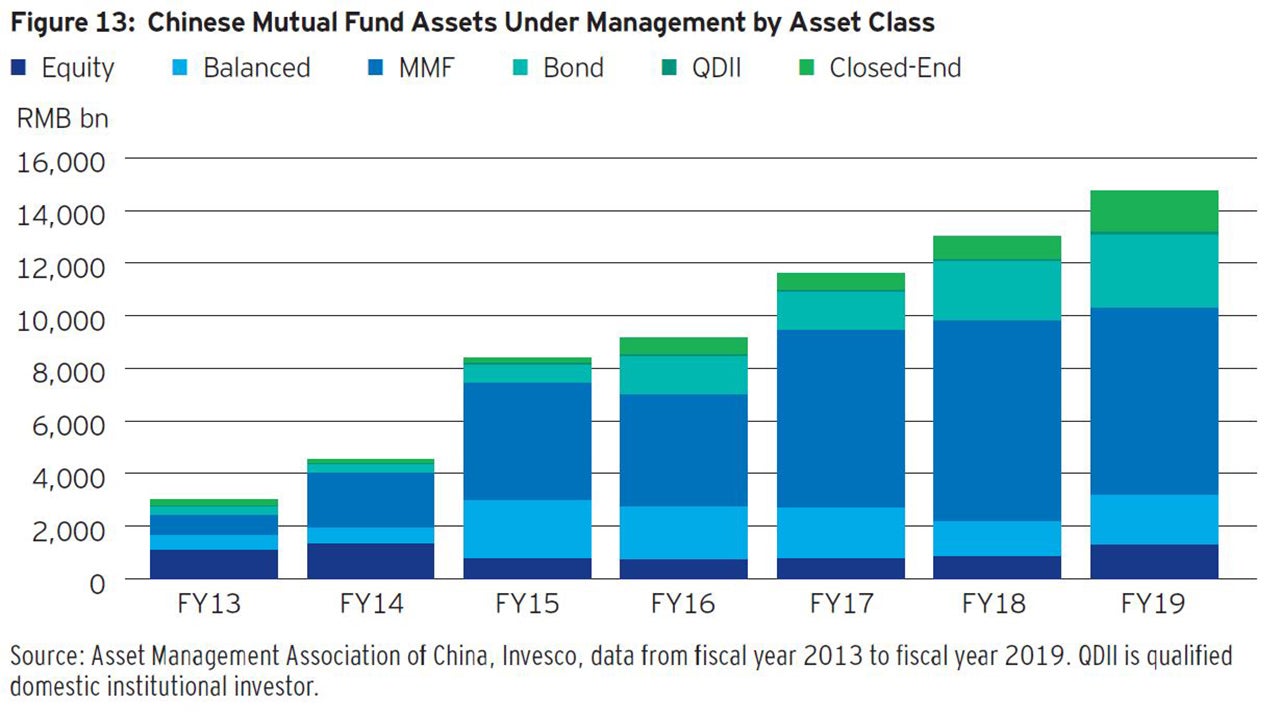

Money Market Funds (MMFs): Chinese MMFs typically offer retail investors a higher yield than the official deposit rate and some MMFs settle on a T+0 basis. Their higher yield and ease of use on major online platforms through mobile phone apps have helped drive rapid growth in this sector in the past few years. Because MMFs have been favored by retail investors over demand deposits, the 7-day annualized MMF yield has been viewed as a de facto “deposit rate.” (Fig. 6). To compete for retail funding, banks have devised various types of cash management products, making official benchmark deposit rates less relevant now for assessing funding costs faced by retail customers.

Monitoring Policy Signals

Official policy measures are also essential to consider when investing in China’s onshore bond market, as they impact both economic fundamentals and market dynamics. Investors look for policy direction from new sector-level regulations and official policy meetings and speeches. Perceived changes in tone have often been followed by tweaks in monetary and/or fiscal policies and shifts in market performance.

Policy Meetings

Politburo and State Council meetings take place frequently, providing economic assessments by top policy makers. The working priorities emphasized during these meetings usually become the focus of ministry-level entities in subsequent months. These meetings are especially important when changes in economic policy begin to emerge. At the Politburo meeting held in July 2019, for example, concerns over an economic slowdown led to an emphasis on stabilizing economic growth. Monetary and fiscal easing measures soon followed in the third quarter of 2019.

Official Minutes, Reports and Press Conferences

Transparency has improved around the Financial Stability Committee, PBoC Monetary Policy Committee and financial sector regulators in recent years, including timely releases of meeting minutes and policy reports, official question and answer sessions and press conferences. These details provide policy guidance and clarification targeted to the financial sector.

Like investors globally, local Chinese investors also carefully compare and contrast wording changes of policy releases to decipher upcoming moves. The addition of the phrase, “reasonably sufficient liquidity,” for example, usually indicates potential net liquidity injections. An emphasis on “keeping the liquidity gate tight,” on the other hand, typically implies a relatively tighter monetary stance. The PBoC also often provides updates and clarifications via its official Weibo (China’s Twitter equivalent) and WeChat accounts.

Sector-Level Regulations

Over the past few years, regulations and policy guidance related to specific industries have affected China’s economic structure and bond market performance. Bank lending to the property sector, for example, has faced tight regulatory oversight at times in recent years and loans to small and medium-sized enterprises have been encouraged through various preferential policies, such as targeted RRR cuts and MLF provisions.

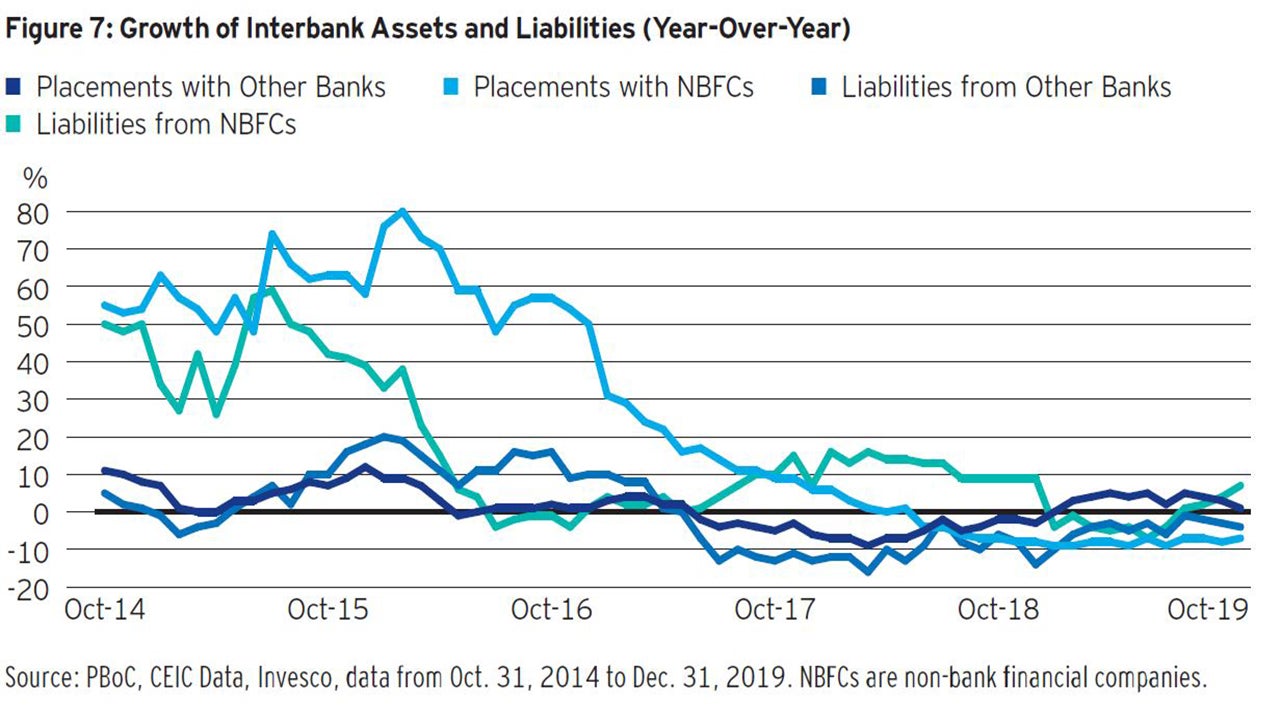

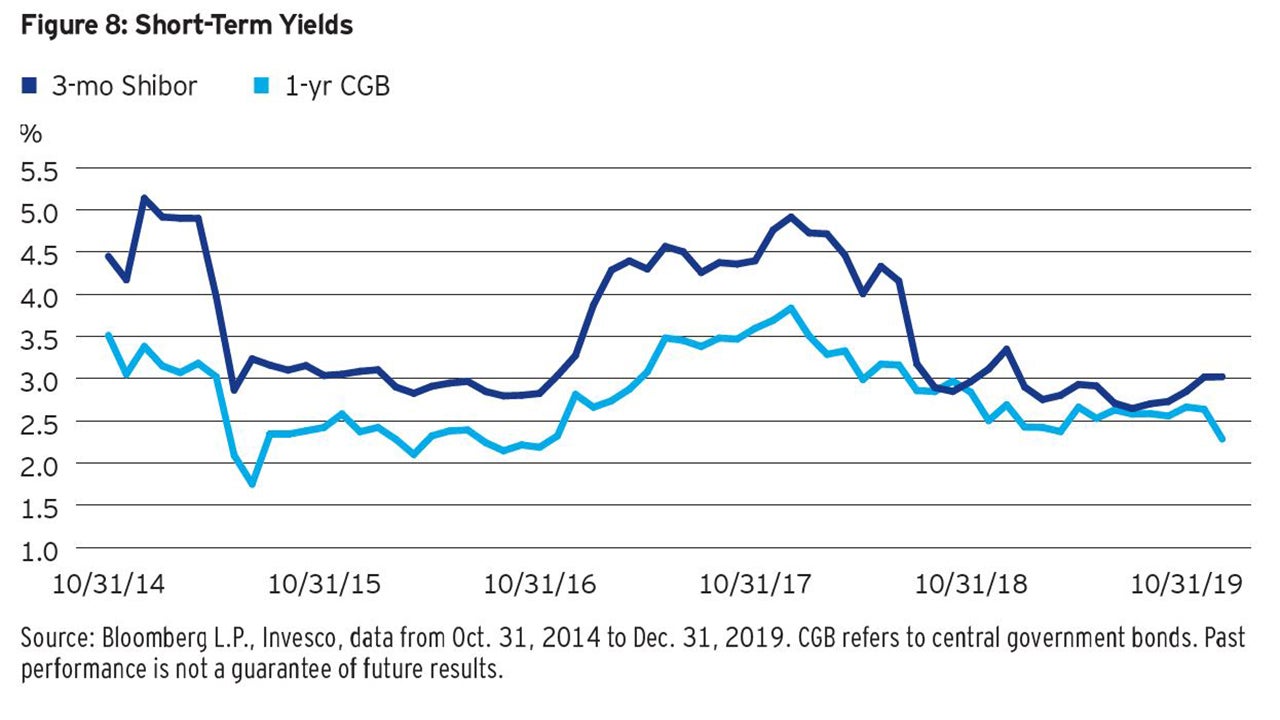

Most recently, macroprudential assessments (MPAs) and asset management regulations have impacted banks’ interbank funding strategies, markets and the economy. Smaller banks have historically relied heavily on lending from larger banks and wealth management products (WMPs) for liability management. But the proportion of funding sourced from the interbank market and WMPs was significantly reduced after MPAs and new asset management regulations tightened oversight, leading to a temporary spike in spike in interbank funding costs and onshore bond market rates (Fig. 7 and Fig. 8).

Importance of Market Structure

Despite strong international inflows in the past few years, local investors still dominate China’s onshore bond market. To be effectively positioned in this market, we believe it is crucial to understand the onshore market’s structure and local investor preferences.

We believe it is especially helpful to understand the asymmetric distribution of liquidity in the interbank market. Primary dealers who facilitate the PBoC’s open market operations typically receive the first-round of liquidity flows, which are then distributed to smaller banks and non-bank financial institutions. Among the primary dealers, large banks typically enjoy a higher proportion of deposits and thus more stable funding with lower costs.

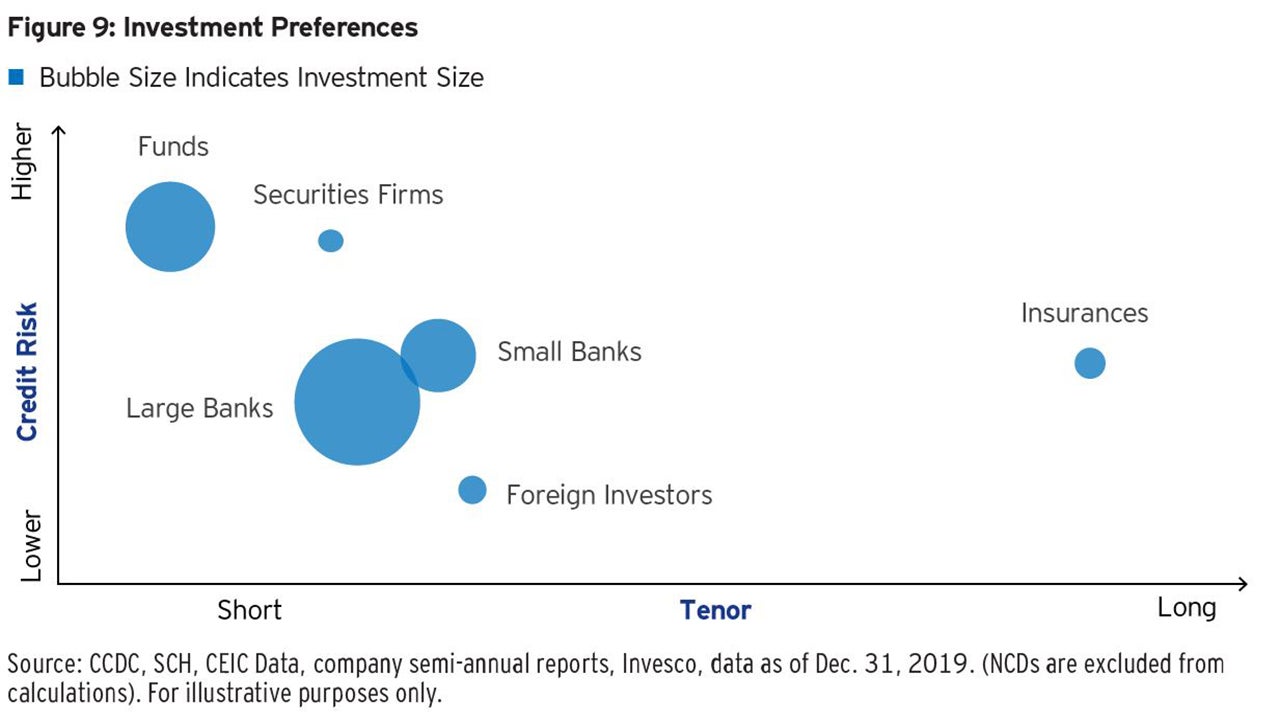

This pattern may help explain why large banks have been more active in rates bonds with relatively longer duration. Non-bank financial companies, on the other hand, have tended to allocate to short-tenor credit bonds, which generally offer higher yields and shorter duration. Insurance companies have tended to favorlonger-duration assets and foreign investors have focused mainly on central government and policy bank bonds (Fig. 9).

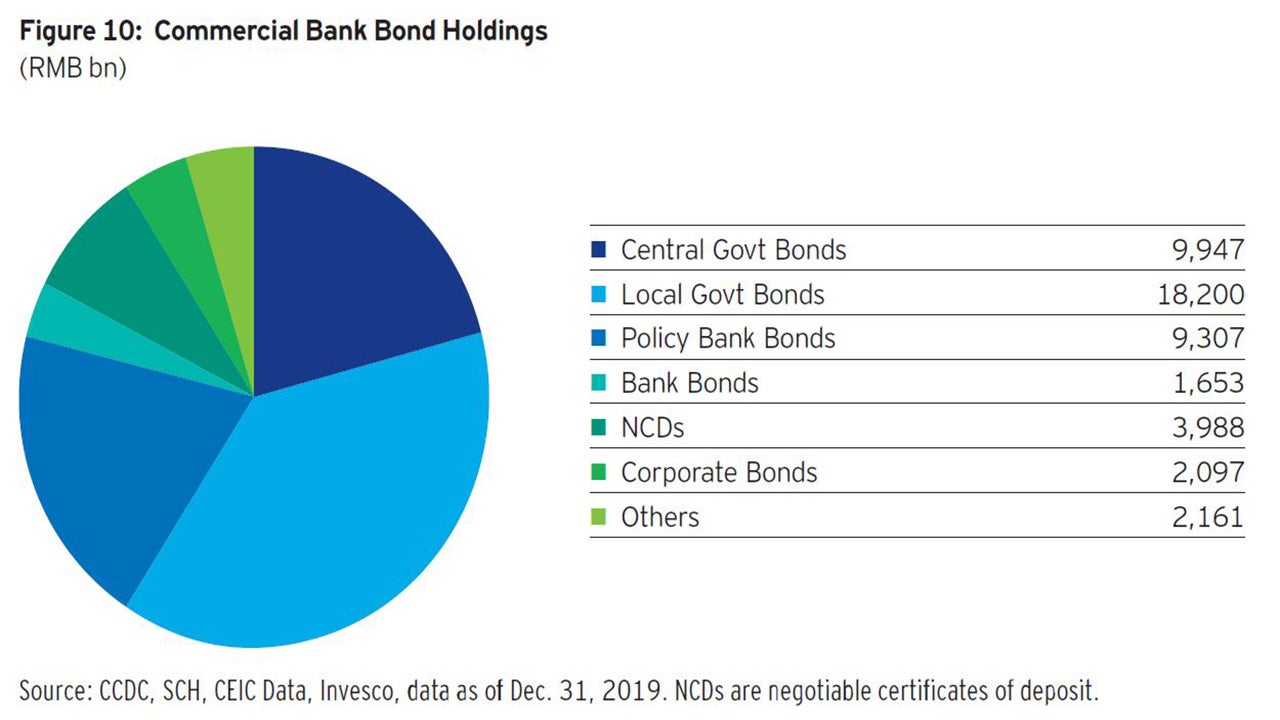

Commercial banks are the main investors in government and policy bank bonds (Fig. 10). This is because banks’ investments involve capital charges and rates bonds typically require lower risk weightings than credit bonds and thus consume less capital. Tax benefits of government bonds are added attractions. The relatively more stable funding structures of large banks also enable investment in relatively longerduration instruments.

Banks generally keep two types of accounts for on-balance sheet bond investments - trading books and investment books. Trading books are more sensitive to yield moves and thus tend to have higher turnover ratios than investment books. Investment books are typically geared toward buy-and-hold investments. Banks also invest in the bond market through wealth management products, which are often categorized separately.

It is interesting to note that in 2019, in the secondary market, large banks reduced some credit positions (on a net basis) and increased investments in rates bonds. City commercial banks, on the other hand, were heavy sellers of rates bonds and NCD holdings, likely due to the funding difficulties faced in mid-2019 by smaller banks after the takeover of a failed city commercial bank (Fig. 11). Rural financial institutions benefited from their relatively sticky retail deposit base and thus were able to support interbank funding.

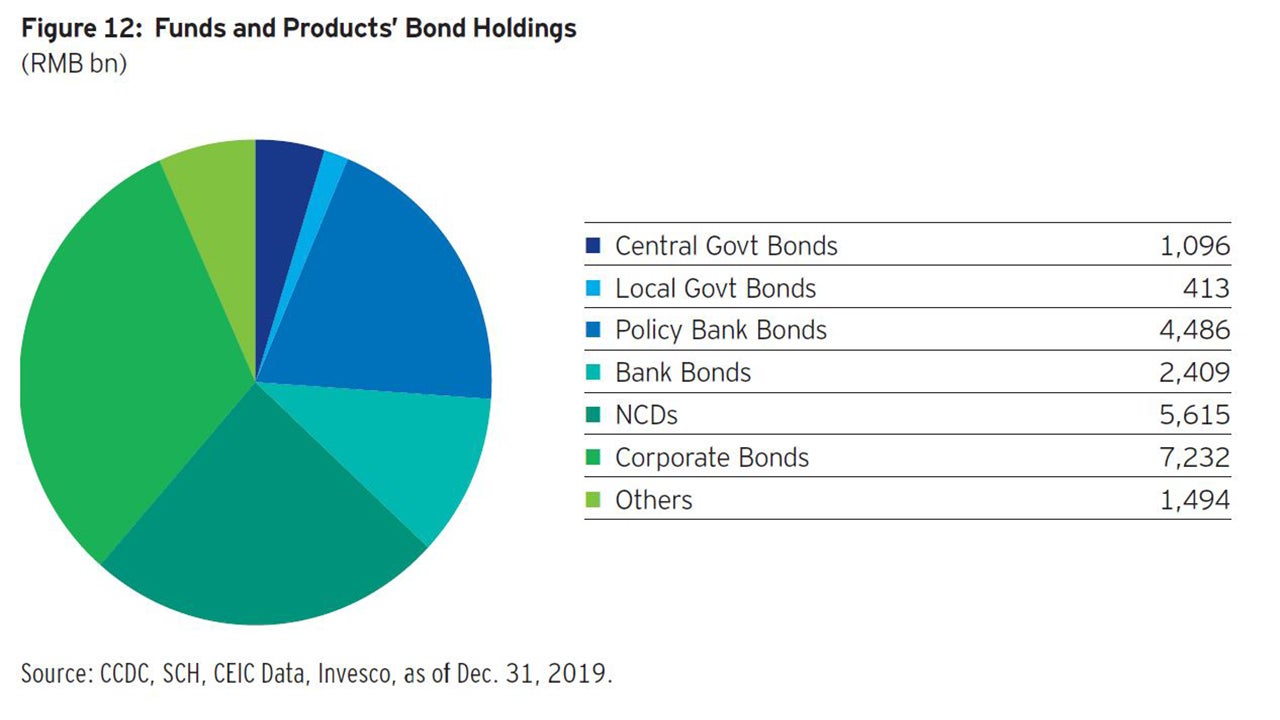

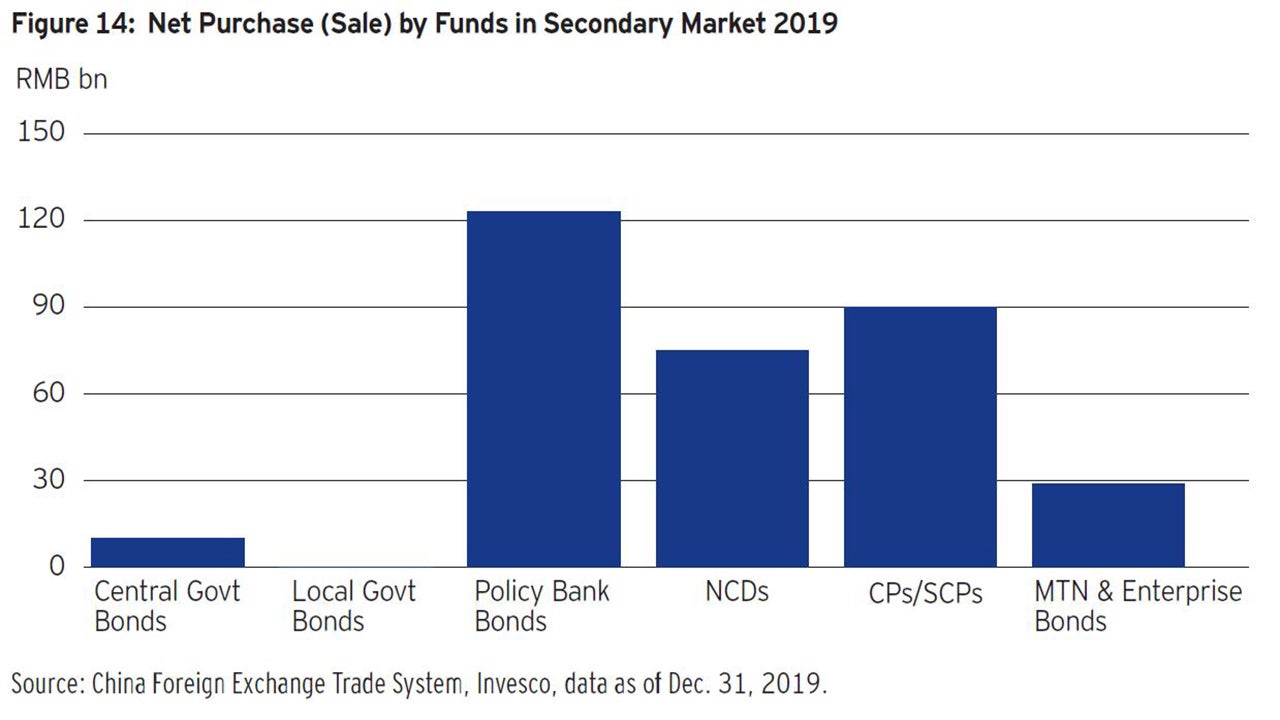

Funds and other investment products are active investors in policy bank bonds, NCDs and credit bonds (such as commercial paper and super short-term commercial paper). Typically, funds have favored bonds with good secondary trading liquidity and tenors have been concentrated in shorter maturities, such as 1-year and below, given their need to manage potential client inflows and outflows. In addition, a large proportion of bond funds are money market funds, most of which must invest in bonds with short maturities and relatively low credit risk. Thus, short-term policy bank bonds, commercial paper, super short-term commercial paper and bank NCDs have become preferred investment choices.

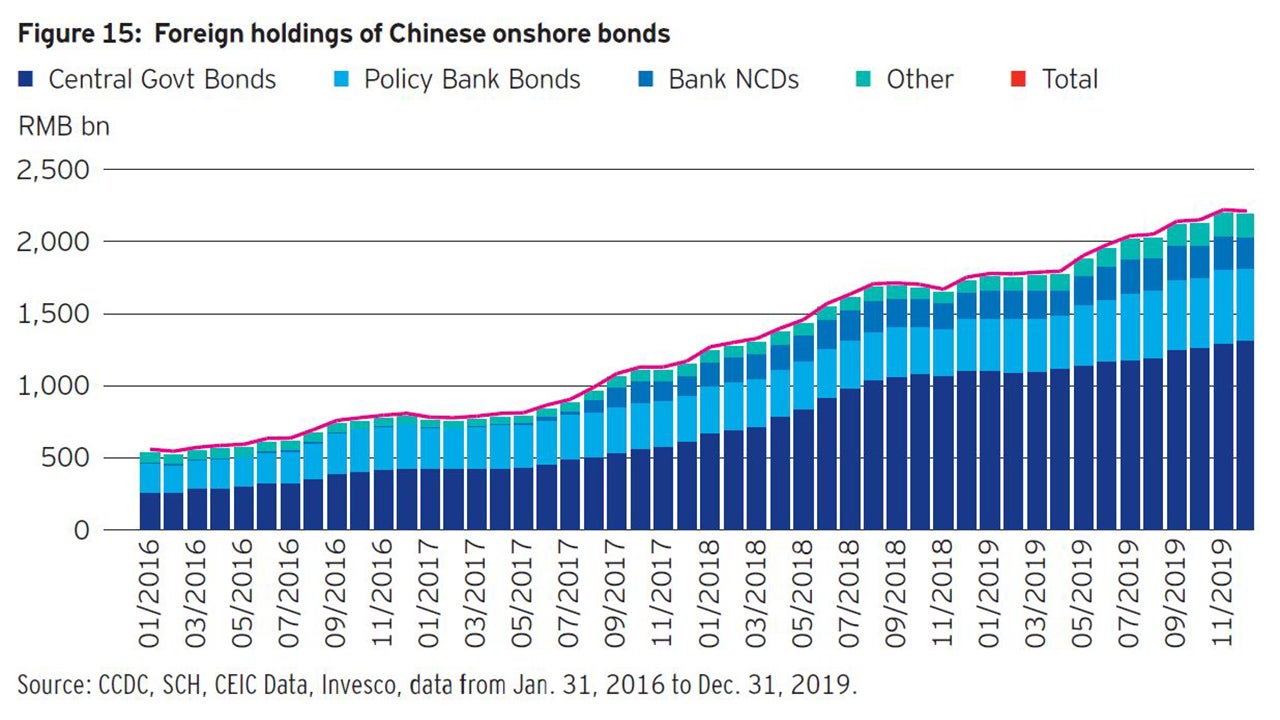

Foreign investors have been a growing presence in China’s onshore bond market in recent years, especially in the rates bond market. Foreign holdings of Chinese onshore bonds totaled over RMB2 trillion (USD314 billion) as of the end of 2019, with the majority of holdings in central government bonds, policy bank bonds and NCDs (Fig. 15). The pace of allocation to Chinese onshore bonds accelerated after major indices included Chinese bonds.

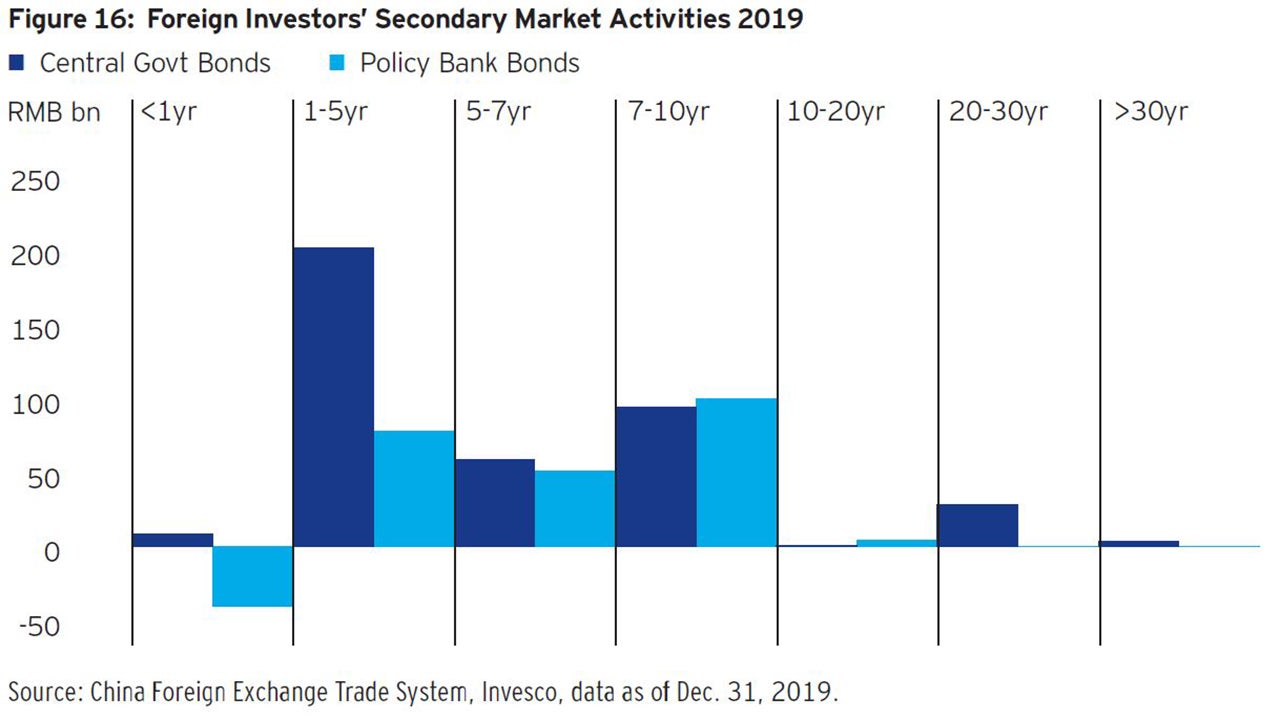

Foreign investors held around 9% of central government bonds as of the end of 2019 (Fig. 15). Around 13% of the net supply of central government bonds issued in 2019 in the interbank market was purchased by international investors. In the secondary market, foreign investors have shown increased demand for longer-duration central government bonds, with a notable increase in allocations to the 20 to 30-year part of the yield curve (Fig. 16).

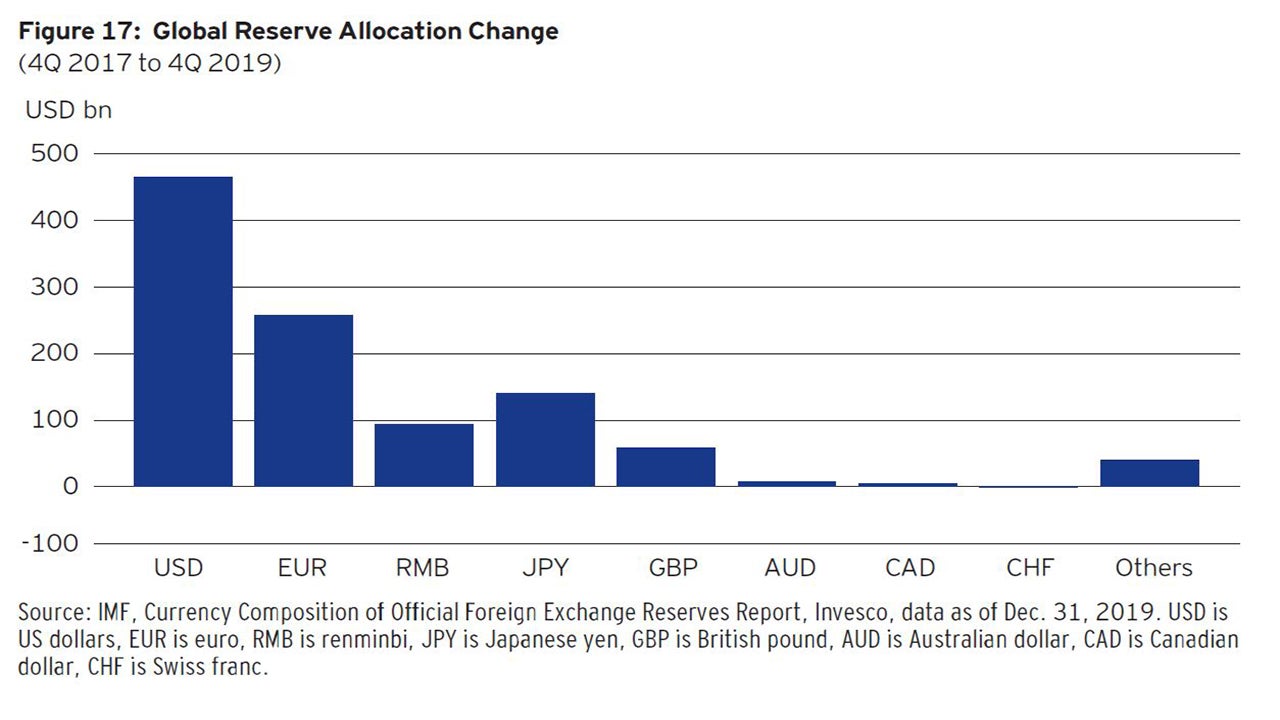

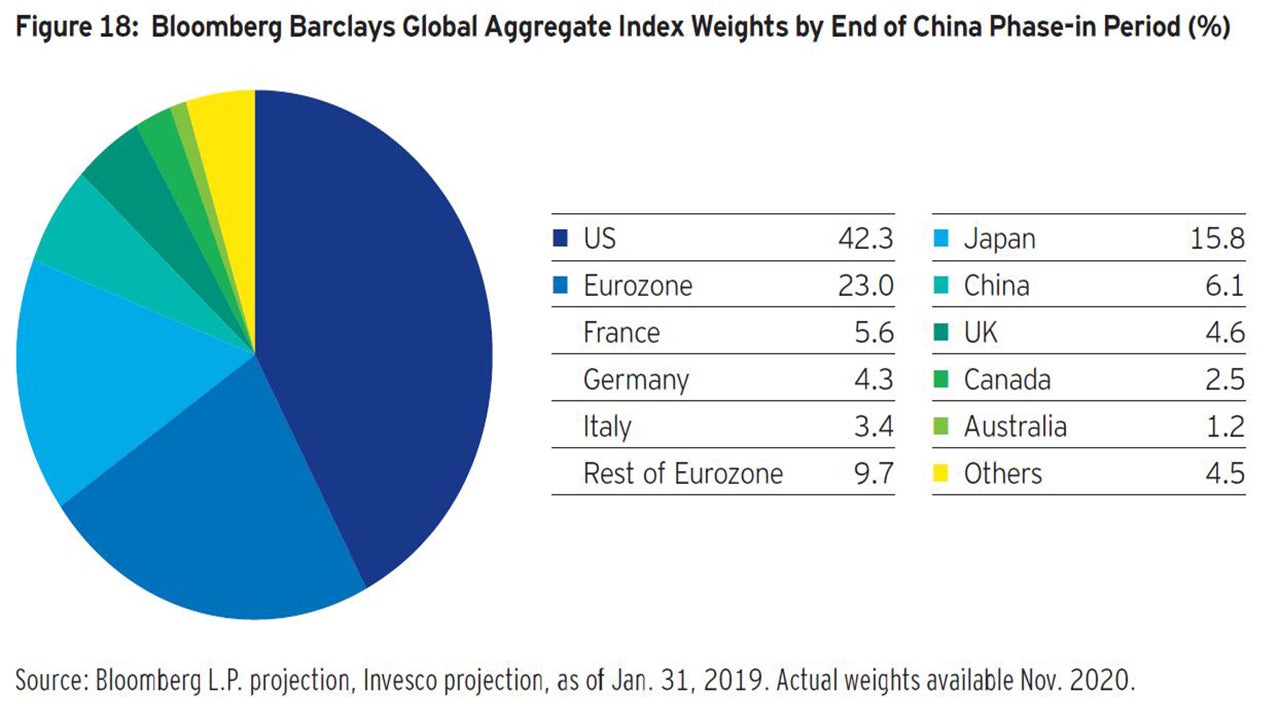

So far, reserve managers and sovereign wealth funds are the largest investors in China’s onshore bond market. Global reserve managers held RMB1.5 trillion (USD218 billion) in renminbi-denominated assets as of the end of 2019, according to the IMF.5 Although the total amount of renminbi investment is still relatively low, the increase in global reserve managers’ allocations to renminbi assets has outpaced increases in investments in British sterling, the Australian dollar and Canadian dollar debt (Fig.17). Bloomberg L.P. expects China’s weight in the Bloomberg Barclays’ Global Aggregate Bond Index to exceed the weights of the UK, Canada and Australia by the end of the phase-in period in Nov. 2020 (Fig. 18).

With additional indices expected to include China’s onshore bonds in the coming year, fund managers may accelerate their investment decisions and allocations to this market. We expect future inflows to originate from 1) countries whose exchange rates tend to move with the renminbi, but that face a lower yield environment and 2) countries whose international trade and investment flows are increasingly linked to China with transactions that settle in renminbi. While government and policy bank bonds currently represent international investors’ main holdings, interest in credit bonds could grow as investors become more familiar with local credit markets, especially local credit fundamentals and bond pricing.

Conclusion

As China has become more integrated into global financial markets, its central bank and other policy makers have become more transparent in communicating policies and policy objectives, enhancing assessment of macro fundamentals and market direction. Macro conditions, regulatory measures and funding profiles have also led to distinct investment preferences among different investor types in China, which are important factors in market dynamics. We believe Invesco’s local presence and familiarity with China’s macro framework, policy nuances and unique market structure enable our team of investors to actively and effectively assess China’s onshore market, as we seek to achieve investment objectives for our clients.

Investment Risks

The value of investments and any income will fluctuate (this may partly be the result of exchange rate fluctuations) and investors may not get back the full amount invested. Past performance is not a guide to future returns.

Fixed-income investments are subject to credit risk of the issuer and the effects of changing interest rates. Interest rate risk refers to the risk that bond prices generally fall as interest rates rise and vice versa. An issuer may be unable to meet interest and/or principal payments, thereby causing its instruments to decrease in value and lowering the issuer’s credit rating. The values of junk bonds fluctuate more than those of high quality bonds and can decline significantly over short time periods.

The risks of investing in securities of foreign issuers, including emerging market issuers, can include fluctuations in foreign currencies, political and economic instability, and foreign taxation issues.

The performance of an investment concentrated in issuers of a certain region or country is expected to be closely tied to conditions within that region and to be more volatile than more geographically diversified investments.

^1 Source: Foreign holdings of Chinese onshore bonds: CCDC, SCH, CEIC, Invesco, as of Dec. 31, 2019. Trading volumes: ChinaBond Watch from China Central Depository & Clearing Co., Ltd., as of Dec. 31, 2019. Index inclusion: Bloomberg announced in January 2019 that the Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate Index would include China’s government and policy bank bonds starting in April 2019 with a 20-month phase-in period ending in Nov. 2020. JPMorgan announced in September 2019 that it will add Chinese government bonds to its emerging markets local currency bond indices starting in February 2020.

^2 Source: PBoC, as of April 3, 2020

^3 Source: PBoC, Bloomberg L.P., as of April 3, 2020

^4 Source: CICC, as of April 7, 2020

^5 Source: International Monetary Fund, Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves Report, Dec. 2019.