Revenue, institutions and elections in emerging markets

Key takeaways

EM governments collect far less tax revenue than is considered desirable, leaving an estimated USD1.5 trillion on the table that could be put toward needed development, such as education, healthcare and infrastructure.

At the same time, young EM voters have been energized to elect more populist-leaning, transparency-oriented governments. Recent studies have shown that greater government transparency could encourage greater tax compliance among the electorate, leading to countries’ improved fiscal health.

While it is too early to label recent youth-led electoral movements in EM a trend, they may suggest better prospects for vital tax revenue collection in the coming years. Better tax collection could boost EM fiscal metrics, improving EM credit quality.

Emerging markets (EM) today are missing out on more than USD1.5 trillion of tax revenue, owing in part to distrust in governments viewed as corrupt. But recent youth-driven elections of anti-corruption candidates could be key to unlocking that uncollected revenue, a potential source of funding for further development and growth.

The evidence is conclusive that low tax collection constrains growth and threatens the creditworthiness of EM sovereign borrowers. EM taxation levels relative to developed markets are low for many reasons, with a key reason being a lack of trust in government. However, in a few recent instances, including Guatemala and Senegal, a surge of young voters helped elect “anti-establishment” candidates campaigning on promises to fight corruption. These promising examples may not yet constitute a durable trend, but they offer a possible template for peaceful transitions to cleaner government and more inclusive growth.

We have seen this pattern before. Georgia, following the election of an “anti-establishment”1 government in 2003 promising to fight corruption,2 doubled revenue collection to 25% of GDP in five years even as tax rates fell. The IMF concluded that this was the result of a “new culture of tax compliance”, with polls showing that tax evasion was no longer considered acceptable.

Growth and taxes

Growth and debt sustainability are both challenged in EMs by tax revenues that are much smaller as a percent of GDP than those collected by their developed market peers. Low fiscal revenue means that productive public investment in areas such as infrastructure, health and education, either doesn’t happen or requires debt.

It is widely accepted that a 15% tax revenue-to-GDP ratio is the optimal minimum level to aim for - and higher is generally better.3 Countries with a tax collection ratio of 15% or lower are typically countries the World Bank classifies as Low Income Countries (LIC) and often do not have public bonds. Although there are some LICs in the JP Morgan EMBI Global Diversified Index (EMBIGD), they represent only 1.2% of its market value.4

The EMBIGD’s weighted average revenue-to-GDP ratio is 25%.5 However, there are some serious laggards. Six countries in the EMBIGD collect less than 13% of GDP in revenue. Iraq collects almost nothing in taxes, financing 90% of its budget by selling oil.6

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) found that the potential rate of tax collection in LICs—if the total amount owed were collected and their tax collection capacity improved—would be 22.2% of GDP versus an average of 13.2% today.7 Given that discrepancy, it seems that 22.2% is an achievable, minimum level that EMBIGD countries should target.

If each EMBIGD country (excluding the petrostates) brought tax collection to that level, governments would take in an additional USD1.5 trillion in tax revenues annually.8 This number includes China, a country now so large, it is often analyzed apart from its EM peers. However, the IMF also wants to see China raise its tax revenue-to-GDP ratio and has recommended various reforms that could increase revenue by five to six percentage points of GDP from its current level of 15.8%.9 Excluding China, the total amount that could be raised through improved tax collection is an estimated USD400 billion. Either way, gathering uncollected tax revenues could make a substantial amount of money available for investment in these countries’ developmental priorities, namely education, healthcare and infrastructure.

Taxes and corruption

Why do these countries collect so little in taxes? EMs typically have limited legitimacy to ask their populations for greater tax contributions, due to perceptions that the governing elite are corrupt. In 2019, the IMF found that “the least corrupt governments collect four percentage points of GDP more in taxes than those at the same level of economic development with the highest levels of corruption.”10

The relationship between a corrupt government and a citizenry’s willingness to pay taxes should make intuitive sense, and the data support the connection. In a study on tax compliance in developing countries, the IMF identified five variables most predictive of a country’s tax revenue-to-GDP collection: public sector corruption, government effectiveness, the size of agriculture in the economy, openness to trade and overall wealth.11 The first two are directly related to corruption.

On the first, the IMF argued that corruption has a “negative relationship with tax revenue collection given its detrimental effect on tax morale and compliance.” The issue of “government effectiveness” is slightly less direct but no less important. A non-corrupt government can be ineffective, but a government’s low level of effectiveness is often related to the misappropriation of resources. The report highlights that “weak [ineffective] tax administrations are not able to collect tax revenues efficiently and may suffer from institutionalized corruption, tax evasion and tax revenue leakage.”12 The other three factors—openness to trade, the overall wealth of the country, and the size of the agriculture sector—are structural factors that can affect tax collection but that are difficult for policymakers to resolve in the short term, and unrelated to corruption.

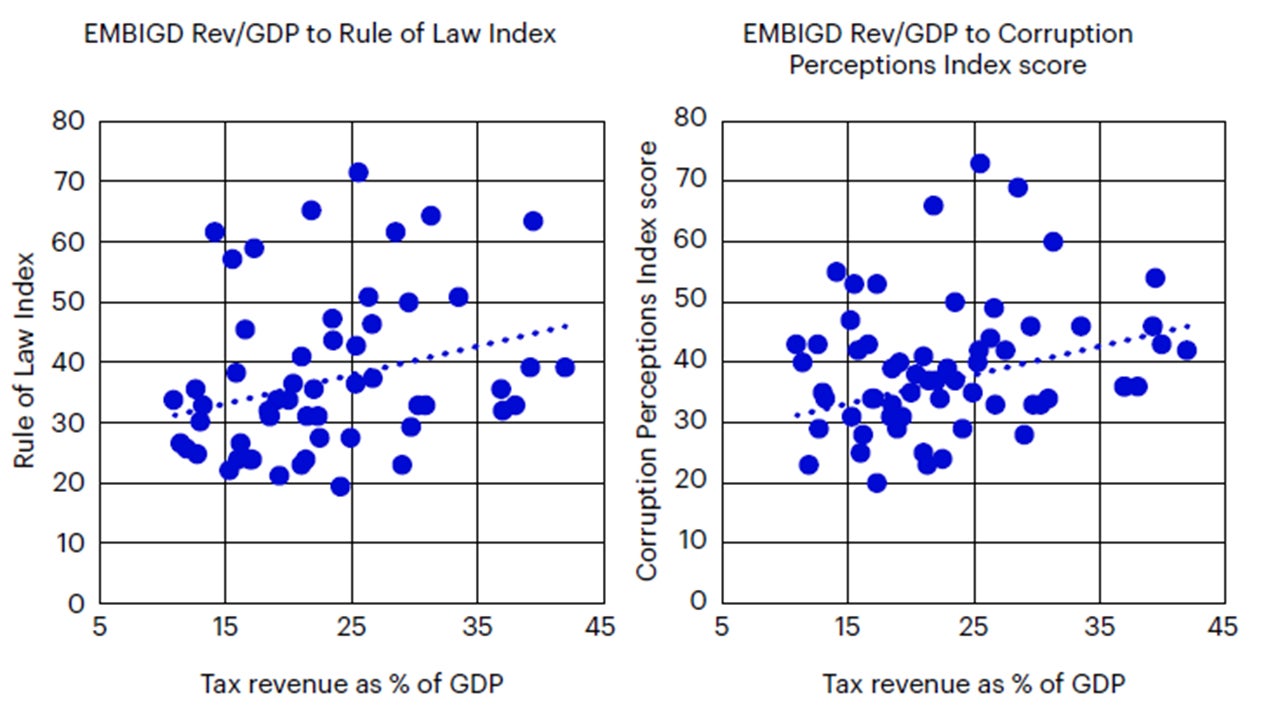

When looking at the members of the EMBIGD, broadly speaking, there is an observable, inverse relationship between levels of corruption and government tax revenue. Leaving aside petrostates, Figure 1 shows that the stronger the rule of law, the more revenue a government tends to raise in taxes.

Source: JP Morgan, IMF World Economic Outlook, World Justice Project Rule of Law Index, Transparency International Corruption Perceptions Index. Data as of Sept. 2024.

Corruption and the young bulge

Several studies have shown that endemic corruption is especially unpopular among the younger portions of the electorate. In a 2023 study by the Open Society Foundation, respondents in over 30 countries—developed and EM—most frequently identified corruption as the single biggest issue affecting their countries.13 Respondents in EMs were more likely to identify corruption than in developed markets. A 2014 World Economic Forum survey of millennials around the world found that 75% of respondents thought that corruption was holding their country back (90% in sub-Saharan Africa), versus 60% in advanced economies.14 So, while there is corruption everywhere, it is especially present in EM and it seen as especially problematic by younger voters.

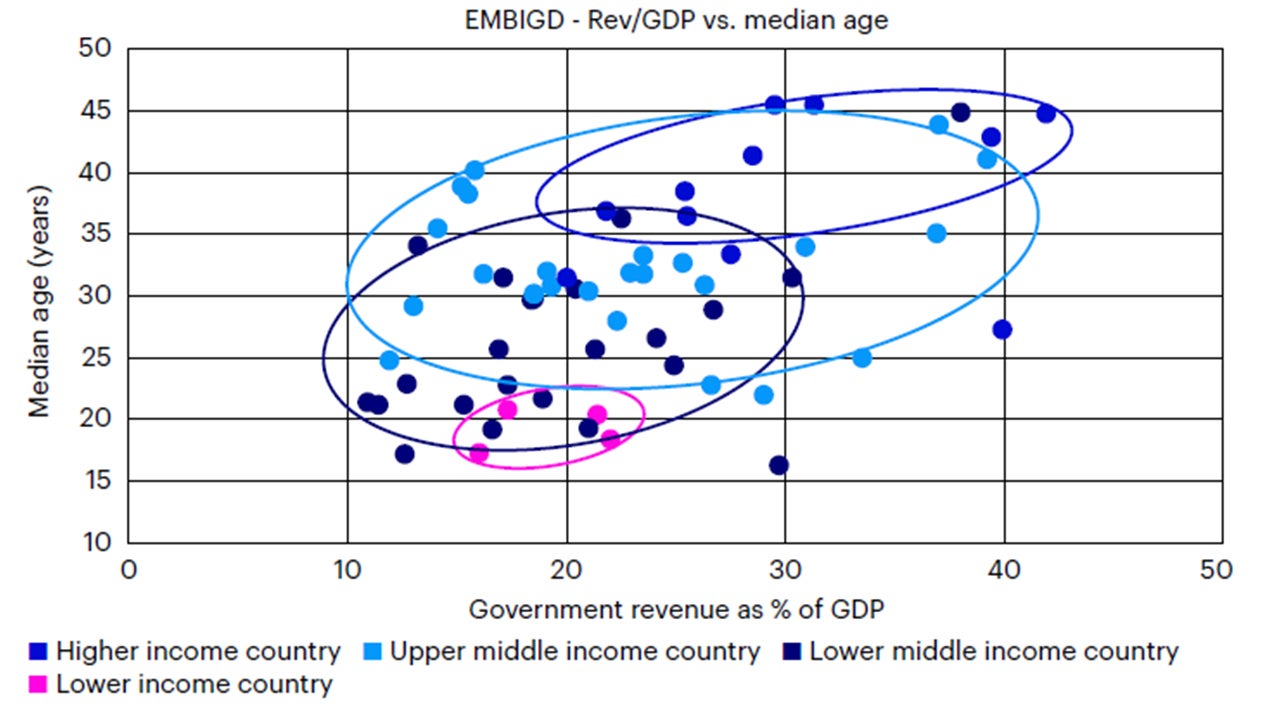

Source: JP Morgan, CIA World Factbook. Data as of Sept. 2024.

This anti-corruption sentiment has made young voters in EM increasingly skeptical of their democratic systems of government, largely because they judge those governments on their observable merits rather than in comparison to a past era they never experienced. In short, they are blaming the system of democracy more than they are blaming the people who happen to be in charge. According to a 2020 study, an “intergenerational replacement is underway” in many EM countries and the young “judge the performance of democracy not in comparison to the authoritarian past, but on the basis of its ongoing challenges—including persistent corruption, the absence of the rule of law, and failure to deliver public goods and services.”15 In other words, young voters in EM today no longer compare their corrupt governments with the dictator or colonial government from 25 or 60 years ago. Instead, they compare their government with an ideal government or a government in a less corrupt country. According to a 2024 African Youth Survey, 83% of respondents said they are concerned about corruption in their country, and 62% believe the government is failing to address it.16 A full 58% say they are “very likely” or “somewhat likely” to emigrate to another, less corrupt country in the next three years.

The opinions of this younger cohort matter greatly in the EM world, given these countries’ young demographics. The median age of EMBIGD member countries is 30.3 years versus 44.5 years in the European Union (EU).17 The median age in LIC countries is in the high teens (the lowest is Angola with a median age of 16 years). Moreover, the younger an EMBIGD country is, the smaller its tax base—meaning there are several countries with a low standard of living, collecting very little in taxes, with a young population that is unsatisfied with this arrangement. While leaving the country altogether or rejecting democracy outright are two options to address the issue, the most obvious and popular method for fighting corruption remains voting.

The youth bulge and elections

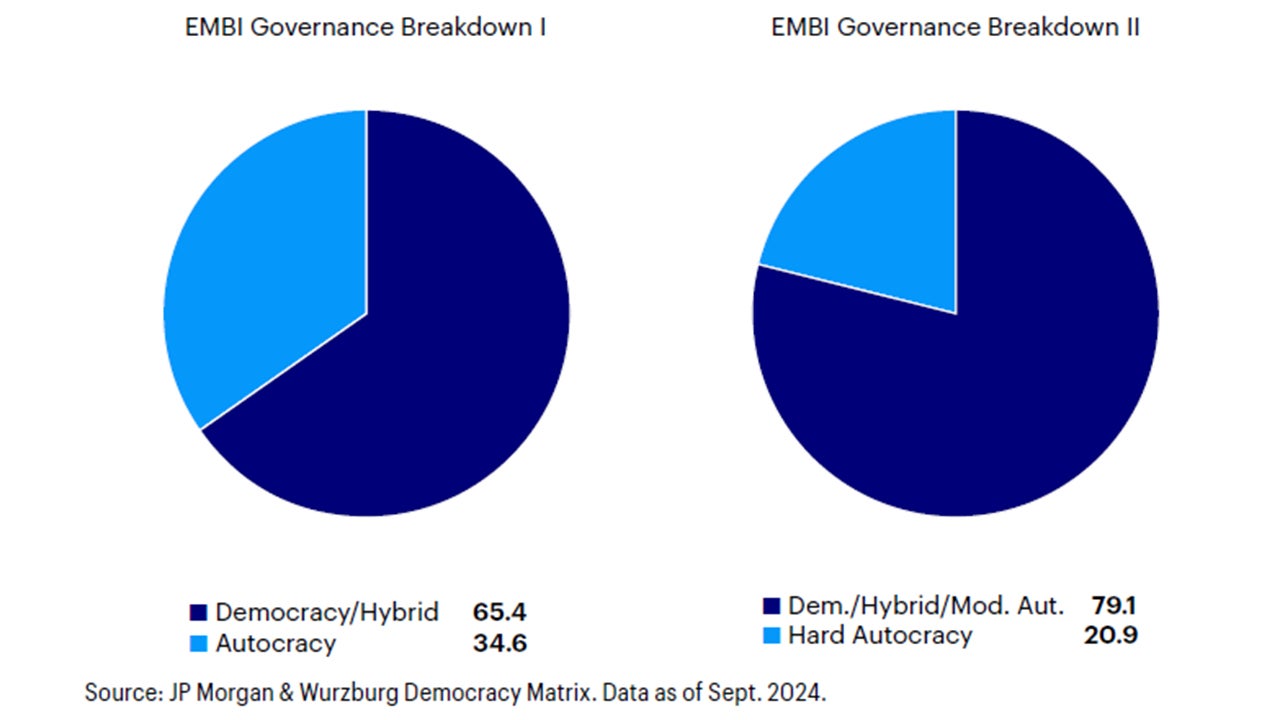

By the end of 2024, 4.2 billion people around the world will have voted in an election, and EMs will make up a large portion of those voters.18 Around 65% of the outstanding bonds in the EMBIGD are issued by countries classified as democracies.19 Just shy of 80% of those bonds belong to countries in a slightly larger group that includes moderate autocracies, such as Turkey and EU member state Serbia, where elections take place but in less-than-ideal conditions.20

Even in imperfect democracies, where the government may exert unfair influence over elections, important developments can still take place at or around election time. At the very least, even an unfair election can serve as a point in time when the government feels at least minimally compelled to justify itself to the people and some kind of opposition is permitted to provide a critique. Whether in a perfect or imperfect democracy, a surge of young citizens—typically less loyal to established political parties or focused on traditional political fault lines, whether left, right, or ethnically based—have a chance to voice their opinions.

Source: JP Morgan & Wurzburg Democracy Matrix. Data as of Sept. 2024.

Elections and “the establishment”

These young voters, angry with corruption, are increasingly finding an electoral outlet with candidates committed to fighting a corrupt “establishment.” Typically, these movements are labelled populist, as they are a mass movement, cutting across typical political structures and aimed at dethroning an elite that is suppressing common citizens. While populism can be used as pejorative, in many instances in EM there is actually a ruling elite conspiring to exploit the population.

The Tony Blair Institute for Global Change studied the global rise of populism and the experience of populists once they have had a chance to govern.21 It outlined three distinct types of populism: cultural populism (focused on social issues – e.g., Victor Orban in Hungary), socio-economic populism (focused on economic issues – e.g., Hugo Chavez in Venezuela), and anti-establishment populism (focused on the capture of government by special interests – e.g., Carlos Menem in Argentina and Lech Walesa in Poland). These last two examples of anti-establishment populism might be surprising to investors generally wary of populism; these leaders are known among EM investors for ushering in periods of economic stability and cleaner governance. While the Blair Institute offers plenty of anti-establishment populists that ended up setting a poor example, the point is that a certain form of populism can bring greater legitimacy to government. With this perspective, the ongoing global wave of populism – especially in EM – may appear somewhat less threatening.

And populism is indeed surging in EM. A poll by market research firm, IPSOS, on populist attitudes around the world showed that EM voters were 17% more likely than voters in advanced economies to agree with the statement that “traditional parties and politicians don’t care about people like me” and 12% were more likely to agree that “the economy is rigged to advantage the rich and powerful”.22

Given these numbers, it would seem that those polled in EM would be less likely than those in advanced economies to agree with the statement, “do you agree or disagree that the [country] government should increase taxes to pay for any additional public spending?” And yet the average for both groups of countries is about the same, at around 18%, even though those polled in EM have a considerably dimmer view of those in power. We cannot conclude from this study alone that voters would be more amenable to paying taxes if governments were cleaner, but the relationship between these conflicting ideas is worth exploring.

Recent examples

Guatemala and Senegal are two recent examples that highlight the potential for a link between faith in government and tax compliance. Events in these two countries do not make a trend, and even they may not end up advancing government transparency and tax-raising capacity. However, they may provide templates of insurgent candidates who take power driven by the youth vote, motivated by cleaner and more representative government.

Guatemala

In August 2023, Guatemalans voted an anti-corruption outsider and underdog, Bernardo Arévalo, into the presidency by a 20-point margin. In a report on the election’s outcome, the US Institute of Peace (USIP) said, “it’s clear that youth participation — both on the campaign trail and at the polls — was a critical component [of victory]”.23 Arevalo ran on a campaign focused on faster and more inclusive economic development and fighting corruption. “Youth are tired of the same old system,” the USIP quoted one civil society activist as saying after the victory.

On the economic front, the IMF has made clear what it thinks Guatemala must do to unlock faster development. In a recent country report, the IMF wrote, “Guatemala needs more tax collection to continue advancing on its path to development … tax revenues are still among the lowest in the world, making it difficult to address the country's pressing needs (e.g., infrastructure, education, health, and malnutrition) without increasing the sovereign debt substantially". The IMF went on to say that the reform agenda outlined in the IMF program can only be achieved by “Strengthening governance with the publication of a national anti-corruption plan and medium-term strategy to combat impunity”, among other things.

Senegal

A similar story is unfolding across the Atlantic in Senegal. The incumbent president, after trying to change the rules to run again, instead appointed a replacement who lost election earlier this year. The winner was Bassirou Diomaye Faye, running as a stand-in for the more popular Ousmane Sonko, who was legally barred from running and is now Prime Minister. The duo are young, former tax collectors (!!!) who ran on promises to combat corruption – both in the form of outright graft and bloated and politicized public spending. While the actual data on youth support for Faye is scarce, journalists on the ground around election time confirmed the youthful nature of Faye’s crowds and volunteers.24

In addition to cutting some subsidies, the IMF’s recommendation to the Senegalese government is to raise additional revenue. According to the last published staff report, “accelerating the medium-term revenue strategy to bolster revenue mobilization, particularly through the reduction of tax expenditures and the broadening of the tax base, is essential.” At the time, the country’s goal was to reach a tax revenue-to-GDP ratio of 20% by 2025, up from 17% in 2021.

Conclusion

Greater government transparency and respect is necessary but not sufficient for EM governments to raise more taxes for badly needed productive investment. Indeed, people do not like paying taxes. But it seems that greater compliance is conditioned on a government’s perceived legitimacy. While Guatemala and Senegal are not far enough along in their efforts to constitute durable success stories, they represent a potential blueprint for an ideal outcome, based on a common set of features often found in EM countries: a low tax base, a young population and a newly elected and popular government promising to fight corruption.

Investment risks

The value of investments and any income will fluctuate (this may partly be the result of exchange rate fluctuations) and investors may not get back the full amount invested.

Fixed-income investments are subject to credit risk of the issuer and the effects of changing interest rates. Interest rate risk refers to the risk that bond prices generally fall as interest rates rise and vice versa. An issuer may be unable to meet interest and/or principal payments, thereby causing its instruments to decrease in value and lowering the issuer’s credit rating.

Non-investment grade bonds, also called high yield bonds or junk bonds, pay higher yields but also carry more risk and a lower credit rating than an investment grade bond.

The risks of investing in securities of foreign issuers, including emerging market issuers, can include fluctuations in foreign currencies, political and economic instability, and foreign taxation issues.

The performance of an investment concentrated in issuers of a certain region or country is expected to be closely tied to conditions within that region and to be more volatile than more geographically diversified investments.