Structural and cyclical shifts signal new market dynamics

Overview

We believe we are experiencing a new market dynamic that is markedly different from the post-global financial crisis period, and we are likely to see a higher level of interest rates as a result. Term premia are very negative, and we believe their potential normalization offers a significant opportunity in rates.

While several shifting dynamics should weaken the US dollar over time, even a simple mean reversion to its long-term average should drive it significantly lower.

Over market cycles, we find a 20% allocation to non-US fixed income is optimal, with a variation between 5% and 30%, given the long cycle of US dollar movements. We believe there is currently a strong argument for an allocation to the higher end of that range.

The Global Debt Team follows a macro-oriented approach and actively allocates risk across interest rates, currencies, and, for some strategies, credit, with an investment horizon of nine to eighteen months. Against a constantly evolving macroeconomic landscape, we explain how we see global economic conditions today and the key trends shaping our views.

Q: What are the main forces currently driving macro and market conditions?

Structural and cyclical forces have combined to make the current period quite different from the period following the global financial crisis (GFC), and we are likely to see a higher level of interest rates as a result. “Recency bias” can lull investors into thinking that the current period is an aberration, and that the post-GFC construct of low inflation and low growth will hold. However, the current combination of elevated spending, potentially higher investment, and low productivity does not necessarily create the same mix.

The structural and cyclical forces at play amid deglobalization and decarbonization have the potential to create a policy mix that increases spending via investment and upends supply chains – which could make inflation stickier than one might expect.

From a structural standpoint, we believe that higher public investment and spending due to decarbonization has the potential to have a multiyear, if not multi-decade, impact on investment – mainly public, but also private. This could lead to higher levels of global growth, which could increase economies’ capacity to sustain higher real interest rates, more akin to the period before the GFC than after.

From a cyclical standpoint, we are starting to see real wages rise again in many economies, as headline inflation falls while delayed wage increases are implemented. Deals struck with US pilots and UPS workers or recent German wage deals, for example, indicate that the effects of wage increases might be felt for some time. While declining, there are still excess savings to cushion the effect of inflation in many regions.

We remain concerned about Europe from a growth standpoint and China due to its ability to export deflation globally. Yet emerging market countries overall have surprised to the upside in terms of economic activity, and we remain constructive on India and Latin America, as interest rates begin to normalize.

Q: US financial conditions have always impacted global markets, but we have seen US policy responses assume even greater importance over the past few years. What seems to be driving this?

The transmission of US policy globally has always been through the impact on the US dollar. Yet this has now extended beyond the currency channel and into interest rates. Since the pandemic, the high degree of uncertainty about the global economic outlook, first regarding growth and then inflation, has made US interest rate policy central to global markets. Unprecedented monetary accommodation in the US gave emerging market (EM) central banks unheard-of policy freedom to reduce their interest rates. Conversely, as US inflation spiked, the US Federal Reserve’s (Fed) subsequent policy tightening reduced EM central banks’ flexibility.

The centrality of US rates globally is problematic for global markets, as it reduces possibilities for countercyclical policy among other developed or EM central banks. The only major central banks employing countercyclical policy are Japan and China, and in both instances, the effect is being felt in both the currency and bond markets. In the case of Japan, it has ended up with higher nominal yields, a steep yield curve and a much weaker currency.

Given the pace and magnitude of policy tightening in the US, along with some financial stability concerns earlier this year, interest rate volatility has remained very high. Unfortunately, the volatility in US Treasuries, a traditional safe haven asset class, is limiting the degrees of freedom for other markets. We expect US rate and currency dominance to continue until there is more clarity on the path of US interest rates.

Q: So far this year, we have seen market expectations shift from US recession to reacceleration, and back again. What are markets expecting now and how might markets react to different economic scenarios?

Global economic performance has been divergent this year; in Europe, we have seen an unexpected slowdown, in China the expected boom never arrived, and in Latin America, despite restrictive policy rates, we have not seen a recession. Given this divergence and the volatility in this year’s economic data – both in the US and other countries – it is not surprising that we are seeing very different pricing in different parts of the financial markets.

In risk markets (i.e., equities and credit), the hard landing and “no landing” scenarios may have similar implications, but for opposite reasons. In the event of a hard landing, markets would likely price in higher risk premia due to greater economic risks, while in the no landing scenario, markets may price in higher risk premia due to persistently higher real interest rates. In either case, however, it appears that insufficient risk premia are currently priced into markets.

Both equity and credit markets seem to be pricing in a soft landing, while the rates market has been pricing in more of a hard landing scenario. The significantly negative term premia in most sovereign bond markets (not just in the US), indicate a divergence between risk markets and rates markets, which the recent bear steepening of the US curve has been correcting.

Q: Where do you see opportunities in global interest rates? Are you focused on the absolute level of rates or on term premia?

For both EM and developed market (DM) interest rates, we care about term premia versus the absolute level of rates. Term premia are currently very negative, and a potential normalization of those premia offers the best opportunity in rates, in our view.

Sovereign interest rates globally have reset to much higher levels than in the post-GFC period. This has led to market debate about whether they are especially high and should, therefore, be “locked in” at current levels. While rates are certainly higher than in the recent past, that does not automatically make them attractive long-term investments, in our view. In any event, “locking in” rates is a misnomer; as rates fall, some income is converted to capital gains and bonds are marked-to-market according to then-prevalent rates.

The question for investors is whether the current level of interest rates is sufficiently attractive to earn excess returns beyond the average cash rate expected over the next few years? The answer to that would be yes, in our view, but not an unequivocal yes, as the current negative term premia in markets is substantial, and to overcome it by just receiving rates may not be feasible in all markets. Simply put, the much-anticipated pivot in global monetary policy is more about the cash rate declining to make longer-term debt returns attractive, rather than expecting long-term rates to fall to generate excess capital gains.

In most sovereign bond markets in developed and emerging countries, the excess return over the risk-free cash rate for holding bonds depends on the term structure of interest rates. Both the actual level of the term structure and the change in the term structure are important. For bonds to return in excess of cash, either the term structure must be significantly positive or becoming steeper. In other words, when interest rates are higher, to judge their attractiveness, we must determine what we think is the neutral level of real overnight rates, the expected level of inflation over the next five years or longer, and what term premium the market will demand.

When we assess the US bond market, we believe the neutral federal funds rate, or so-called r*, is now higher than before the pandemic. We estimate it to be between 0.5% and 1.0%. We expect inflation to fall to 2% to 2.5% and remain fairly stable, and the term premium, given the large supply/demand imbalance, to be between 1.0% and 1.5%. This suggests a range for the US 10-year Treasury yield of 3.5% to 5%. We make similar assessments for other markets, and other than for a few markets, such as Brazil and Mexico, the outcome is the same. The current level of interest rates is in the middle of our expected range, and we believe the primary opportunity for excess returns is through term premia normalization, rather than the absolute level of rates.

As a result, our outright overweight positions are in select EM countries, such as Brazil, Mexico and Colombia, while we are focusing on extracting potential changes in term premia in most other markets.

Q: What might the impact of the three possible economic scenarios (hard, soft or no landing) be on currency markets?

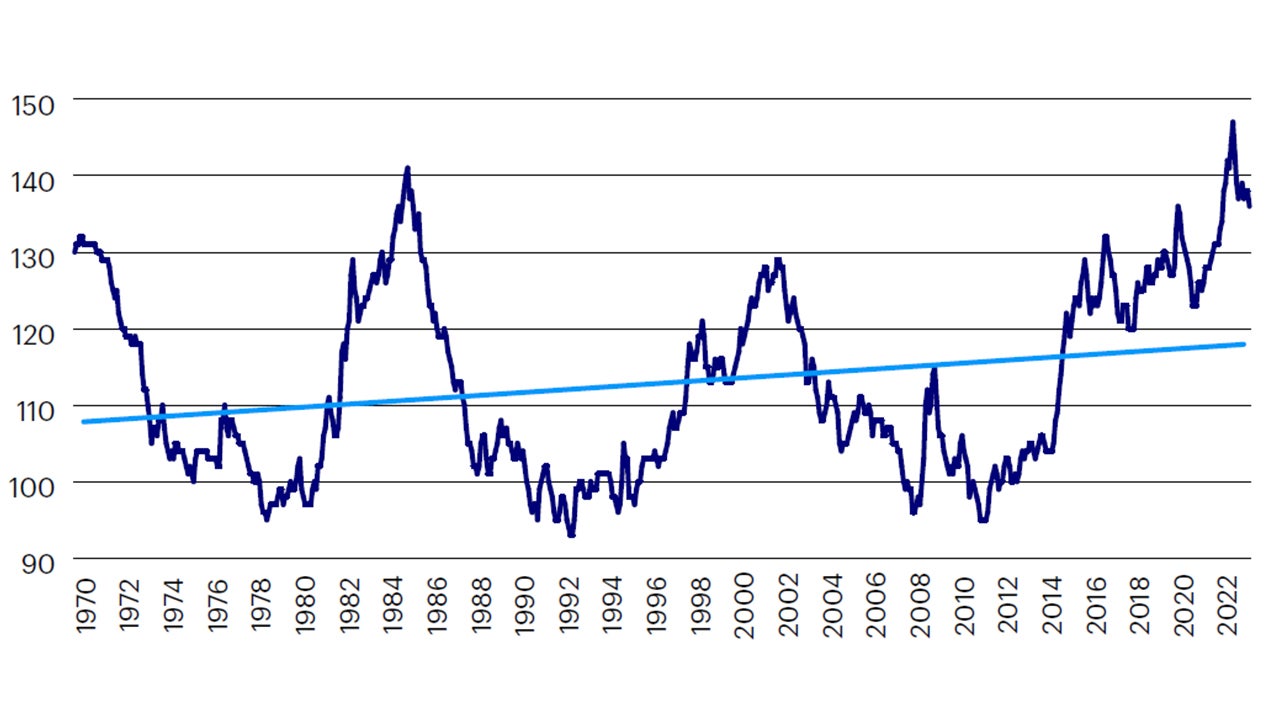

While down from its high last fall, the US dollar is still close to a 50-year high in real effective terms. There are several cyclical and structural dynamics that should continue to weaken the dollar over time, and a simple mean reversion to its long-term average should drive it significantly lower.

From a monetary policy standpoint, while relative policy differentials are important, the absolute direction of US monetary policy matters more, in our opinion, and we believe it is peaking in terms of restrictiveness. Looser fiscal policy will likely also be a cyclical drag on the US dollar, in our view.

Structurally, we are not only starting from high valuations, but also from a high level of ownership. Most global institutional investors are overweight US dollar assets. In addition, deglobalization and decarbonization have the potential to reduce the demand for US dollars over the longer term, as excess savings in many countries would likely get absorbed by the large capital expenditures required in those countries.

Of the possible economic outcomes, a global soft landing remains our central forecast, in which inflation falls and stays around 2-3%. In this scenario, the US dollar would likely weaken as the Federal Reserve would be able to normalize interest rates to neutral without a recession. Risk assets would likely not correct significantly and that too could allow the dollar to weaken in an orderly manner. In such a scenario, we would continue to favor EM currencies over DM currencies.

In the other scenarios, the outlook for the US dollar would likely be more mixed. In a hard landing, risk-off scenario, we would not expect significant dollar strength. Rather, we would anticipate something similar to the Silicon Valley Bank episode in March, when the dollar rose, but due more to the unwinding of positions than a secular move. We would expect EM currencies to underperform relative to the funding currencies. Since the dollar is not the primary funding currency at this time, the effect on the dollar of a hard landing scenario would likely be more muted compared to similar periods in the past.

In a no landing scenario, US rates would likely stay higher for longer, and long-term interest rates could rise too. As the market adjusts, we could see some temporary dollar strength, but again we would not expect it to be significant.

Q: Given your expectations for a weaker US dollar, how do your macroeconomic views influence your stance on currency exposure? Are you focused on EM currencies versus the US dollar, or is the main driver likely to be DM currencies?

Our current currency stance is based on our baseline view that economic growth will likely be resilient, with a low risk of recession over an investment horizon of six to twelve months. We believe the global monetary policy cycle is peaking as inflation declines to a level slightly above central bank targets.

Our investment thesis, therefore, is focused on extracting the real interest rate differential between EM and DM currencies. Currently, real policy rates in EM countries are rising as disinflation takes place at a faster rate than in DM countries. Over the next six to twelve months, we expect real EM policy rates to converge with those of DM countries. At that point, our focus would likely shift toward DM currencies.

As such, we remain underweight the US dollar versus higher yielding (and higher real yielding) currencies, while remaining long the US dollar versus lower yielding currencies, such as the Chinese renminbi and the Taiwan dollar.

Source: Bank of America. Data as of July 31, 2023.

Q: Given this macroeconomic backdrop, what is your view on global credit?

We favor being underweight credit from a purely valuations standpoint. We believe that credit assets that are generally exposed to US economic risk are fairly expensive – credit has been bid up amid attractive yields and a lack of economic stress. Yet they are vulnerable to the two types of tail events discussed above: persistently high interest rates or a hard landing. Given that there is no valuation rationale to support being fully invested, we favor an underweight.

Q: Global investing has been out of favor for the past several years, alongside the strong US dollar, but global fixed income markets tend to be mean reverting. How should investors think about global investing within an overall fixed income asset allocation?

We view global fixed income as a core fixed income allocation. Over market cycles, we have found that a 20% allocation to non-US fixed income is an optimal mix; however, given the long cycle of US dollar movements, we believe that a more dynamic asset allocation is appropriate, varying between 5% and 30%.

Given the long period of underperformance of international assets due to the strength of the US dollar, combined with the economic, cyclical, and valuations backdrop we just discussed, we believe there is currently a strong argument for a current allocation at the higher end of that range.

Investment risks

The value of investments and any income will fluctuate (this may partly be the result of exchange rate fluctuations) and investors may not get back the full amount invested.

Fixed-income investments are subject to credit risk of the issuer and the effects of changing interest rates. Interest rate risk refers to the risk that bond prices generally fall as interest rates rise and vice versa. An issuer may be unable to meet interest and/or principal payments, thereby causing its instruments to decrease in value and lowering the issuer’s credit rating.

The values of junk bonds fluctuate more than those of high quality bonds and can decline significantly over short time periods.

The risks of investing in securities of foreign issuers, including emerging market issuers, can include fluctuations in foreign currencies, political and economic instability, and foreign taxation issues.

The performance of an investment concentrated in issuers of a certain region or country is expected to be closely tied to conditions within that region and to be more volatile than more geographically diversified investments.