Weak dollar, strong emerging markets

Overview

The US dollar has experienced significant weakening year-to-date, although from a very strong starting point, and we think this trend is set to continue.

Positive capital flows can potentially drive better returns in EM – especially in local currency bonds – and, therefore, we think EM is positioned for continued outperformance.

We believe emerging markets (EM) fixed income assets are well positioned for continued strong returns, as a significant rotation away from the US dollar is pushing capital into EM, attracted by its robust growth and solid economic fundamentals. Flows to both hard and local currency EM debt have been deeply negative for the last four years, leaving ample room for dedicated buyers to return, especially given EM’s high absolute yields and a growing likelihood of lower interest rates in the US. We believe the coming year is an excellent opportunity to gain exposure to EM, and with minimal differentiation. We believe a rising global macro tide will likely lift most – if not all – EM boats in the coming year.

The dollar’s crooked smile

The “dollar smile” is the idea that the US dollar appreciates both when US growth is exceptional and corporate earnings are high, but also when there is a market selloff and a broad-based flight to quality. Those two scenarios are the corners of the smile, while the trough is when US growth is moderate and global growth is stronger.

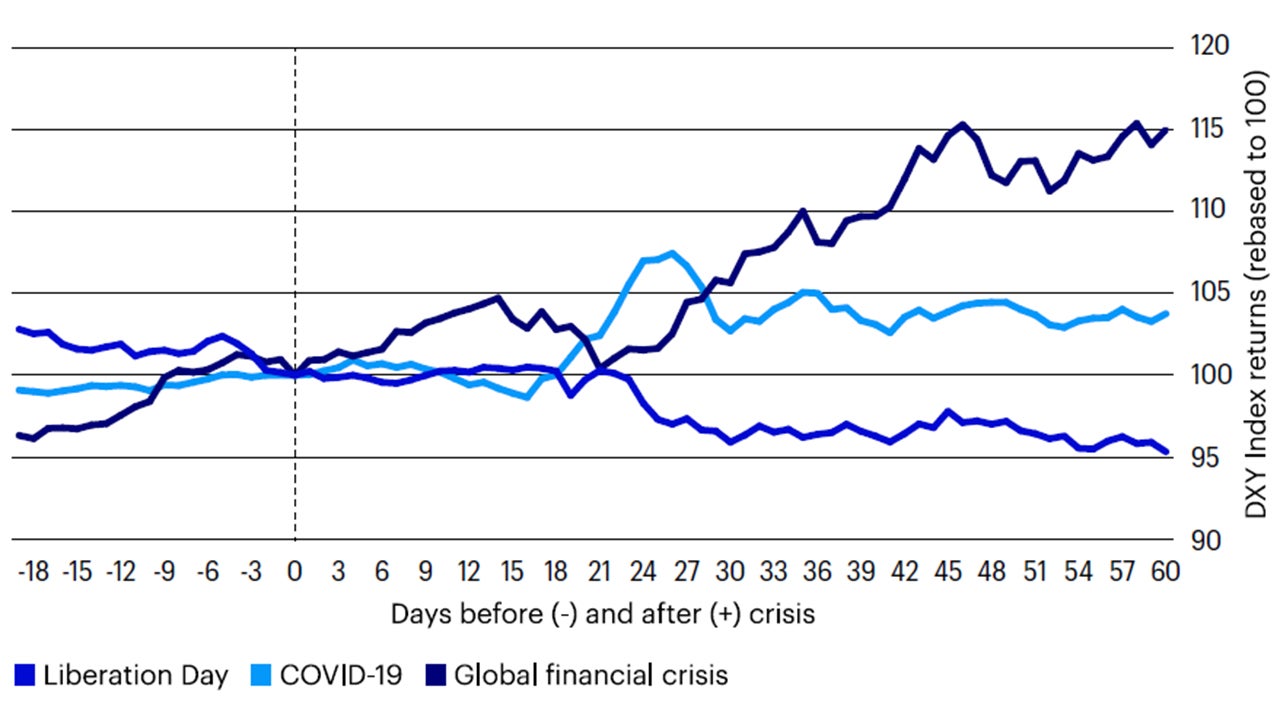

However, this relationship broke down recently, and looked more like a “crooked” smile. Stock and bond markets sold off in the wake of US President Trump’s Liberation Day announcement of elevated and broad-based tariffs on US trading partners (Figure 1). But interestingly, the dollar sold off as well. A weak US dollar strengthens local currencies and tends to drive capital flows to EM countries. We believe the driving forces behind this unusual US dollar weakening are likely here to stay.

Source: Bloomberg L.P. Data as of August 11, 2025.

The rise of US dollar dominance

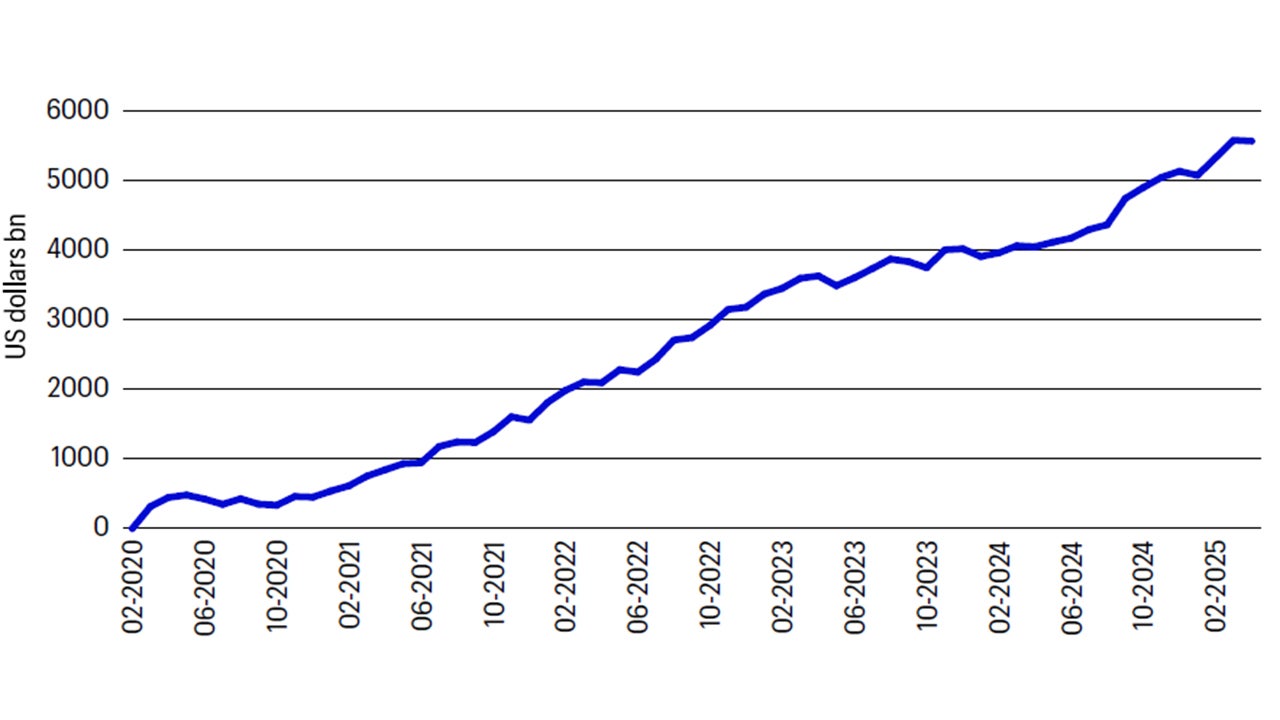

To put the US dollar’s recent decline in context, it is important to understand how historically strong it was at the start of 2025 and the reasons for that strength. The US Federal Reserve (Fed) began a hiking cycle in March 2022. By 2023, the US 10-year Treasury yield was at 15-year highs and came within a few basis points of 5%.1 During this aggressive rate hiking cycle, the broader US economy managed to avoid a recession. Hype around a potential AI revolution was gaining steam and US technology companies seemed to be at the forefront. Against that backdrop of elevated yields and a resilient economy, certain US equities and fixed income offered attractive returns. Elsewhere, EM countries struggled with their own post-COVID inflation and debt woes, Europe’s growth lagged as it dealt with security and energy issues, and some foreign capital began questioning the longer-term viability of China as an investment destination. This funneled capital into the US. According to the US Treasury Department, the US received USD5.5 trillion of portfolio inflows (foreign purchases of US government and corporate debt and equities) from just before the COVID pandemic to the present (Figure 2), or around 18% of 2025 nominal US GDP.2

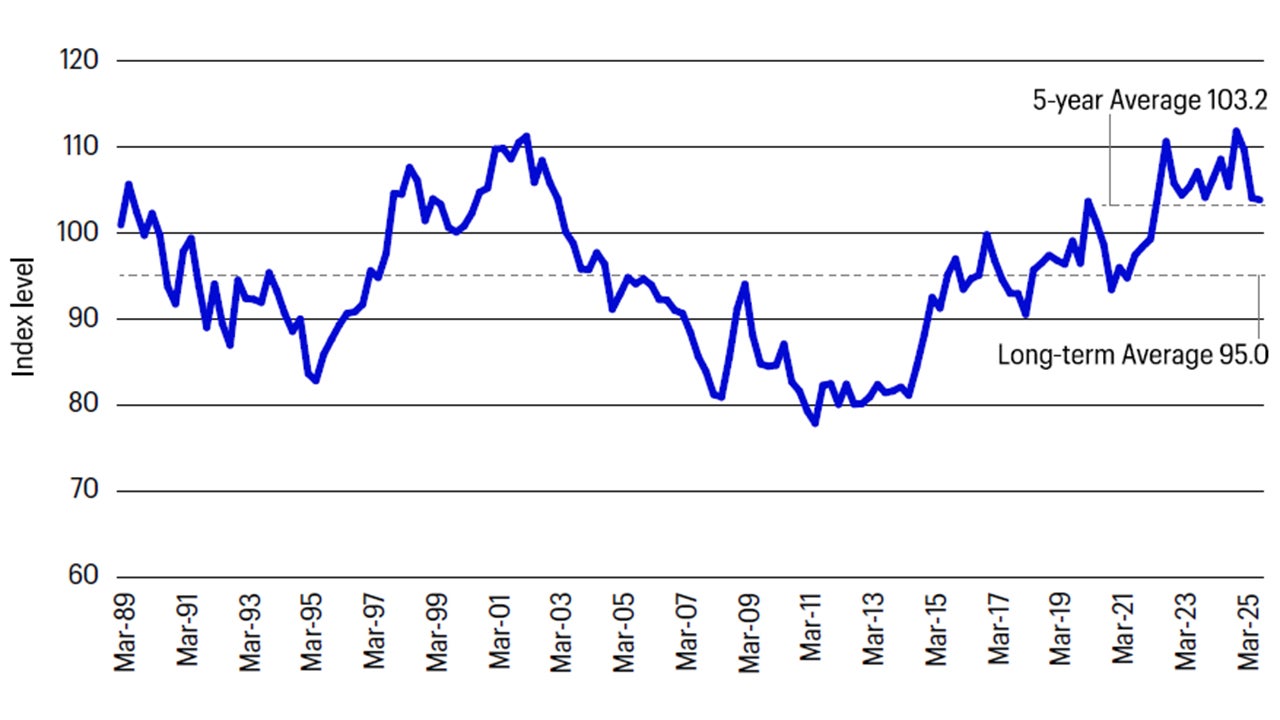

This surge of inward investment pushed the US dollar well above its long-term average and kept it there for three years (Figure 3).

Source: International Monetary Fund. Data from Feb. 1, 2020 to April 30, 2025.

Source: Citi Broad Real Effective Exchange Rate Index – US dollar. Data from March 31, 1989 to July 2, 2025.

This US dollar strength hurt EM countries by making it more difficult to repay US dollar debt they had incurred during periods of low US interest rates. The strong US dollar also came at EMs’ expense as they lost out on portfolio flows needed to finance their current account and fiscal deficits.

Is US exceptionalism waning?

Since late last year, however, that glow of US exceptionalism has begun to dim. By the end of 2024, the S&P 500 Index closed at an all-time high and traded at a P/E multiple of 24x – higher than its five and 10-year averages and close to multiples last seen around the height of the tech bubble in 2000.3 Only weeks earlier, Donald Trump had won the November election, promising a crackdown on immigration, tax policies that suggested a larger budget deficit, a remaking of some economic institutions in Washington and – most importantly – the aggressive use of tariff policy to reshape the global trading system.

With valuations rosy and policy uncertainty ahead, on April 2, President Trump unveiled a series of tariffs considerably worse than the market expected. In January, Chinese technology companies emerged to offer stiff competition to US tech giants when DeepSeek burst onto the scene with an AI chatbot that rivaled existing US versions. We believe these worries about US stock valuations, Trump’s use of tariffs, falling US rates, and threats to US technology dominance are likely here to stay.

An opportunity for EM

While some market observers seem to believe this is the end of the US dollar’s dominance, we believe the current action in the dollar is more likely a substantial and swift correction from a period of immense strength and overweight positioning by global investors. Nevertheless, these kinds of corrections have historically benefited EM.

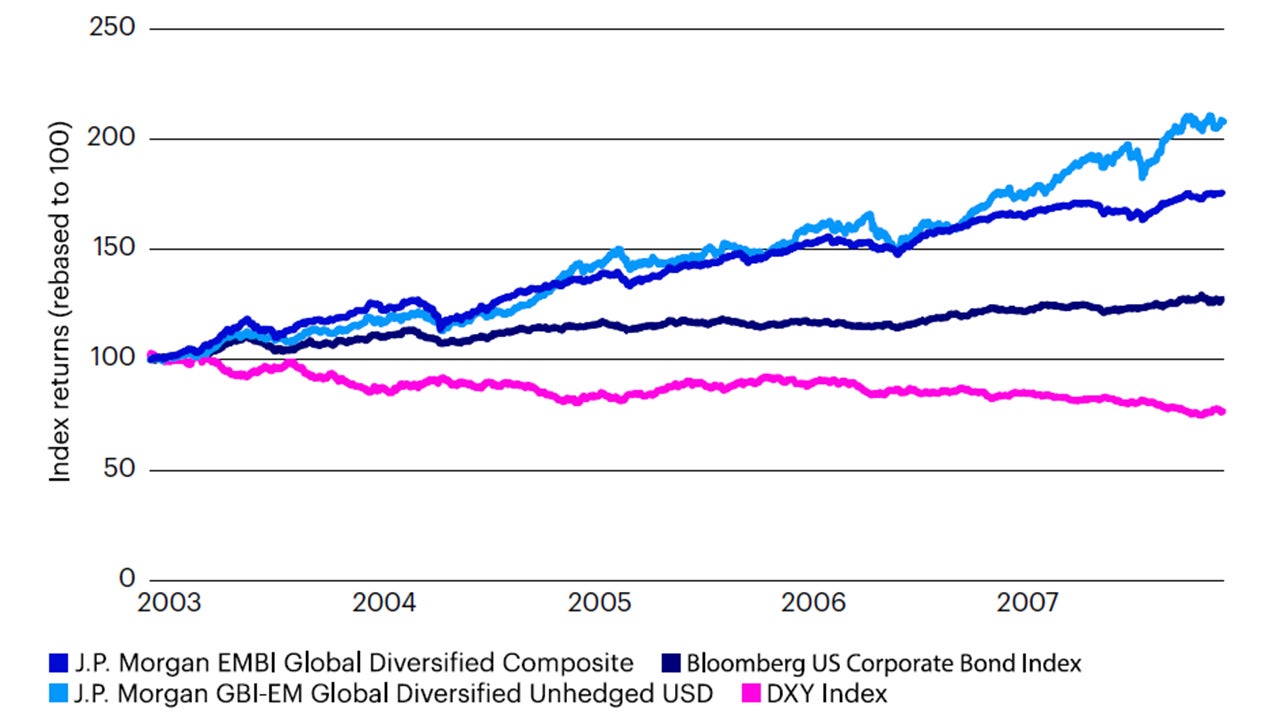

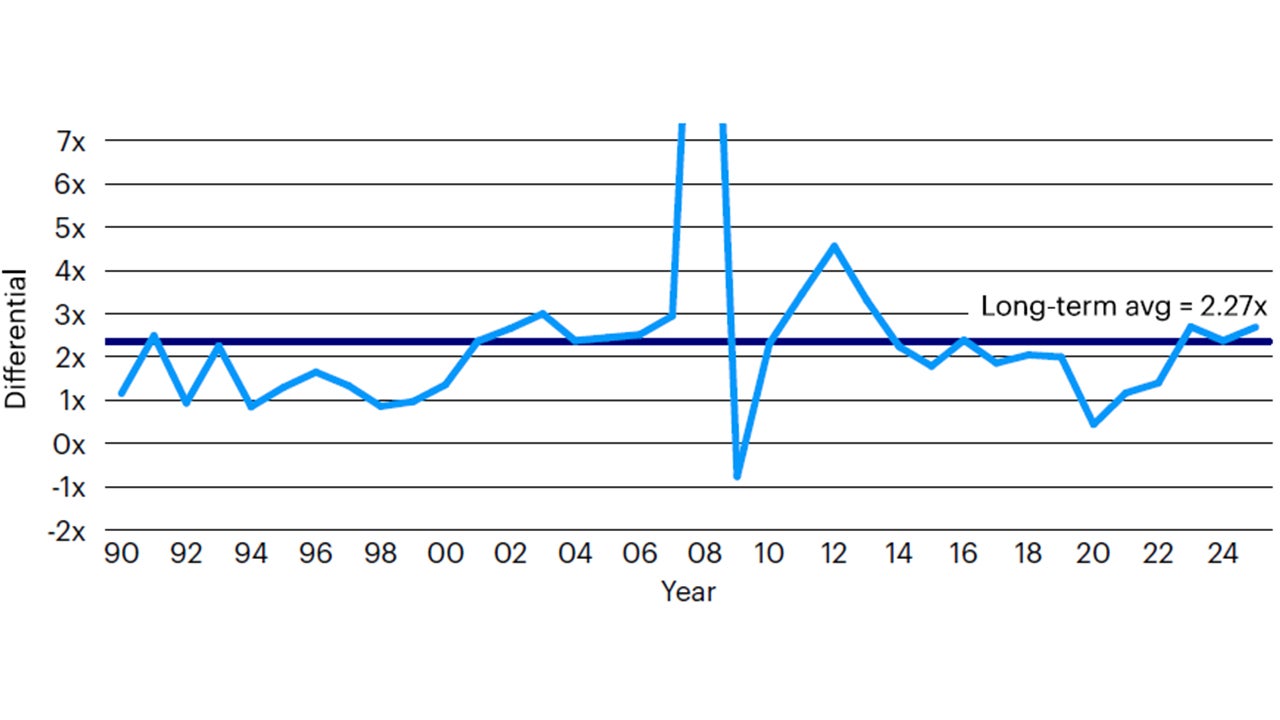

EM local debt is especially sensitive to US dollar movements – it has a 0.71 correlation on a quarterly basis with the U.S. Dollar Index (DXY).4 In some ways, today’s landscape is similar to an earlier period of EM credit outperformance from 2003 to the global financial crisis in 2008. During that period, EM credit outperformed US credit thanks to strong fundamentals and a weakening US dollar (Figure 4).

Source: Intex. Data from Jan. 1, 2018 to Dec. 31, 2024.

Besides the favorable global macro backdrop, EMs are also conveniently in a strong economic and institutional place. The average EM credit rating currently stands at BBB-, which is the highest level it has ever achieved. And the EM growth differential with developed markets (DM), at 2.69x in 2025, is above its long-term average and close to the differential seen in periods of EM asset price outperformance (Figure 5).

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook. Data from 1990 to 2025 forecast.

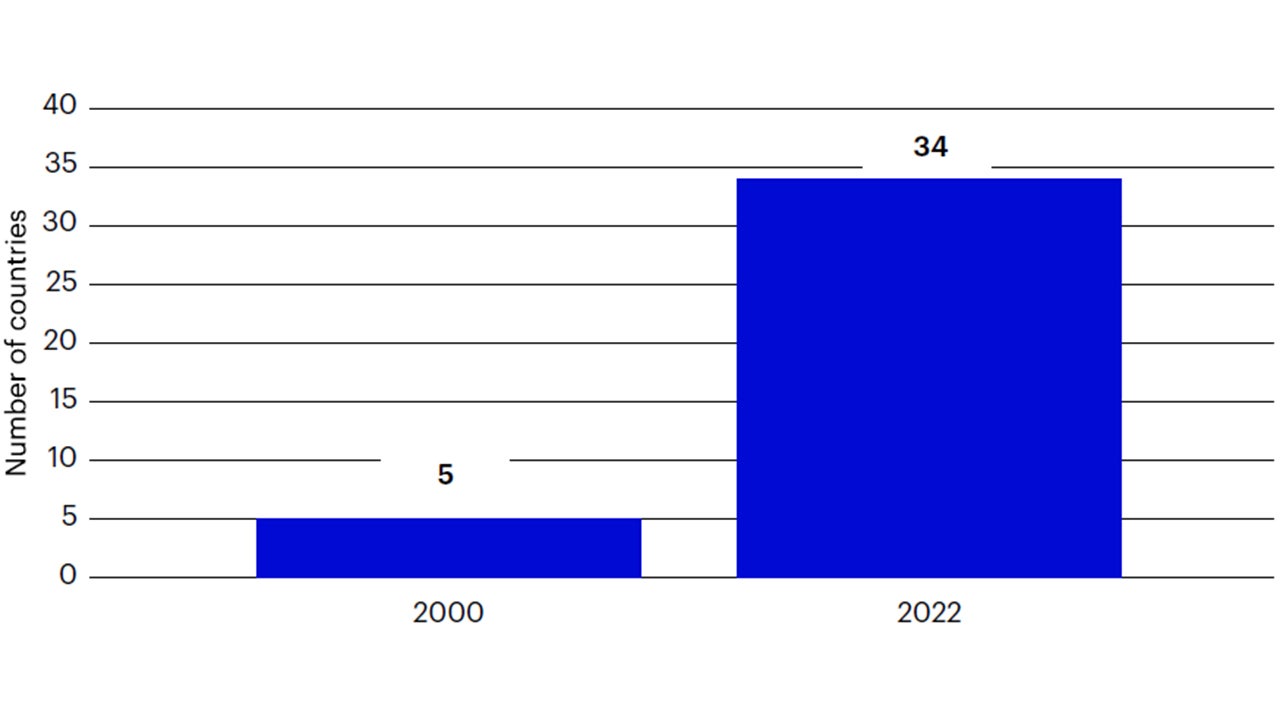

EM’s higher growth rate has been helped by stronger and more entrenched institutions, with the number of EM central banks with a credible inflation targeting regime six times higher over the last twenty years (Figure 6).

Source: International Monetary Fund, Steering through the Fog: The Art and Science of Monetary Policy in Emerging Markets, May 7, 2025.

Orthodox central bank policy during the post-COVID inflation surge carried the major EMs through the crisis with minimal damage, and have left them positioned to start a rate cutting cycle – which should further boost growth.

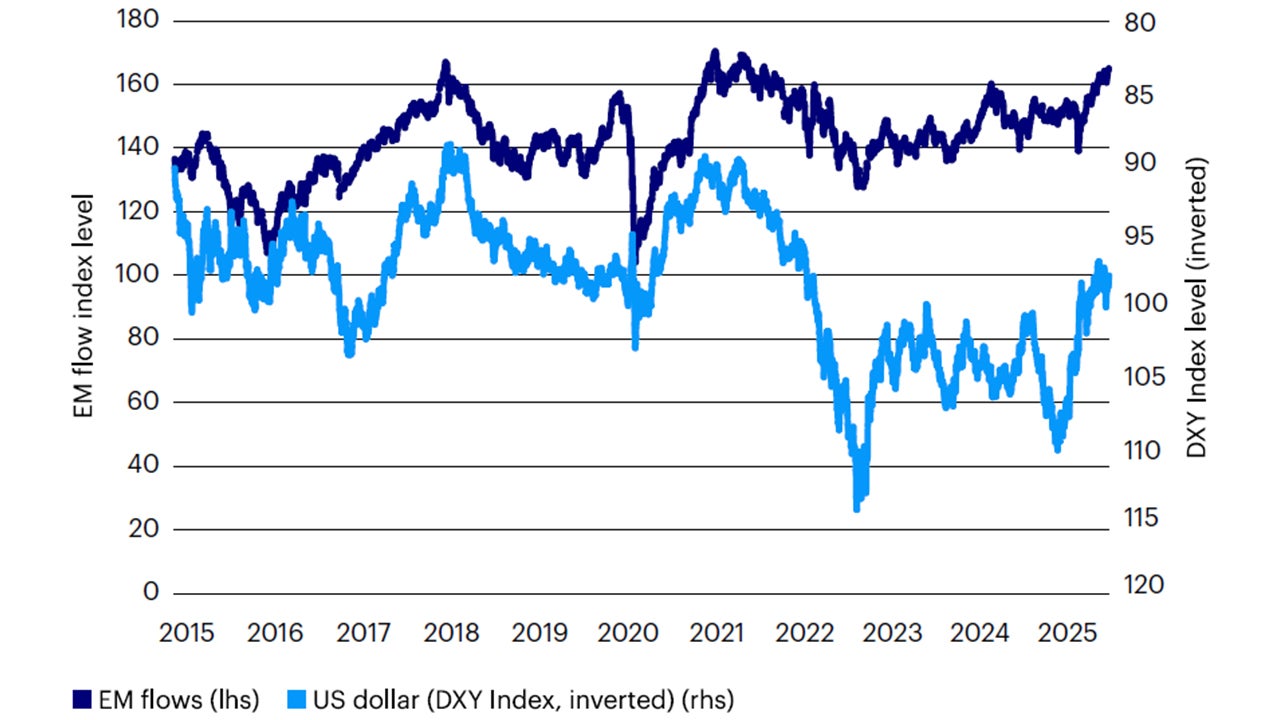

US dollar weakness and EM performance

As long as the US dollar continues to weaken, we believe EMs should benefit. Historically, periods of US dollar weakness have driven flows to EM as the investor base has rapidly expanded, which has driven returns in the asset class (Figure 7). Morgan Stanley believes that a 1% fall in the US dollar results in about USD360-USD440 million of inflows into local currency debt.5 Even in a broader market scare, EM local 10-year bond betas to overall global risk sentiment have tended to fall when the US dollar is weakening.6 This offers some comfort around owning EM in the event of a global risk-off environment.

Source: Bloomberg L.P. Bloomberg Emerging Markets Capital Flow Proxy Index, DXY Index. Data from April 29, 2005 to August 12, 2025.

The absorptive capacity of the asset class is also growing. EM tradable debt has grown 13% annually for the last 25 years, reaching USD44 trillion in 2024, including USD39 trillion in local currency and USD5 trillion in hard currency debt.7 Market technicals are currently relatively clean, with global investors lightly positioned in EM assets – especially local bonds.

Conclusion

We think questions around US exceptionalism are likely to persist in the medium term, while EM’s strong fundamentals seem set to endure and EM institutions are likely to keep improving. As global investors rebalance away from the US dollar, we believe EM offers a compelling opportunity for diversified growth and resilient returns.

Investment risks

The value of investments and any income will fluctuate (this may partly be the result of exchange rate fluctuations) and investors may not get back the full amount invested.

Fixed-income investments are subject to credit risk of the issuer and the effects of changing interest rates. Interest rate risk refers to the risk that bond prices generally fall as interest rates rise and vice versa. An issuer may be unable to meet interest and/or principal payments, thereby causing its instruments to decrease in value and lowering the issuer’s credit rating.

Non-investment grade bonds, also called high yield bonds or junk bonds, pay higher yields but also carry more risk and a lower credit rating than an investment grade bond.

The risks of investing in securities of foreign issuers, including emerging market issuers, can include fluctuations in foreign currencies, political and economic instability, and foreign taxation issues.

The performance of an investment concentrated in issuers of a certain region or country is expected to be closely tied to conditions within that region and to be more volatile than more geographically diversified investments.