Applied philosophy: Are commodities too optimistic?

Most assets welcomed signs of a thawing in trade relations between the US and the rest of the world. Commodities, however, have given us mixed signals year-to-date with energy commodities remaining near lows due to expectations of increasing supply, while industrial metals recovered. Gold seems to be the closest to pricing in a recession in the US. Although the probability of that happening in the near term seems lower than in early-April, risks remain to our Overweight allocation to cyclical commodities.

The relief has been anticipated for about a month. Perhaps this was the plan all along. Threaten to push up tariffs to extreme levels only to use them as leverage in trade negotiations. Unfortunately, they will most likely end up at higher levels than before the “Liberation Day” announcements with 10% as a new baseline. As we outlined earlier in May (see here for more detail), this could still lead to a slowdown that seems inconsistent with recent returns on risk assets.

In early-April major equity indices reached levels implying a significant slowdown in growth: the S&P 500 fell 19%, the Topix 18%, the Stoxx 600 16% and the MSCI Emerging Markets (EM) index dropped 13% compared to their respective year-to-date peaks in late-February and early-March (total returns all in local currency terms as of 20 May 2025). Despite persistent policy uncertainty in the US, these indices recovered to within touching distance of their Q1 2025 peaks leaving them in positive territory for the year apart from the Topix (as of 20 May 2025 in local currency terms).

Global fixed income indices for government bonds, investment grade and high yield moved little year-to-date and their total returns are just above flat for now (as of 20 May 2025, using Bank of America Merrill Lynch indices in local currency terms). At the same time, they are caught between expectations of lower growth and higher inflation in the US, which may have pushed yields in opposite directions.

Real estate returns have been similar to equities year-to-date falling 15% by early-April although their recovery has been less complete as they are still down 7% (as of 20 May 2025 using the FTSE EPRA/NAREIT Global Index in local currency terms). I think their sensitivity to interest rates may have restricted their recovery as futures priced in fewer rate cuts than earlier this year.

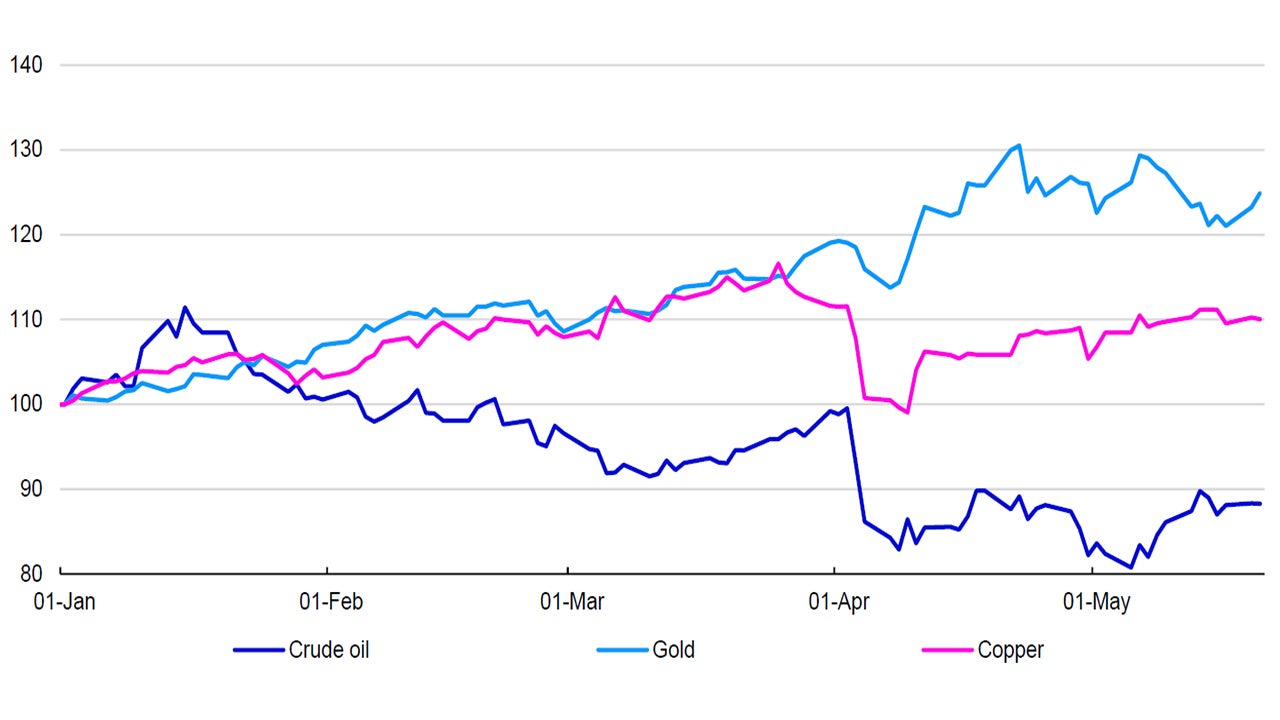

However, where the picture gets really muddled, in my opinion, has been in commodities, a cyclical asset class that tends to have its own “super-cycles”. In a world where US dollar assets have not been able to play their traditional role as so-called “safe havens”, gold became the ultimate expression of flight to safety. On the other hand, energy and industrial metals could be exposed to a cyclical slowdown in global growth (see Figure 1). How much of that may have been priced in came up as a question in recent meetings with investors.

Notes: Data as of 20 May 2025. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. We use the West Texas Intermediate Cushing Spot prices for crude oil, London Metal Exchange Grade A Cash for Copper and London Bullion Market prices for gold. We use daily data starting on 1 January 2025 rebased to 100.

Sources: LSEG Datastream and Invesco Global Market Strategy Office

It is not always easy to extract signals from the movements of commodity prices as their relationship with global GDP can be characterised as loose at best. This may be partly due to the lag between changes in demand and the response in supply. A further complication in this cycle is the outsized impact of the post-COVID supply crunch and normalisation. This has left most commodity prices significantly lower than their 2022 peaks.

Nevertheless, I think we can assume that, after an initial burst of optimism when the result of the US presidential election was announced in November 2024, concerns about US growth have resurfaced only this year driven by the aggressive tariff policy of the Trump administration. Commodity returns in 2025 so far have diverged significantly, as I would expect given the uncertainty around economic growth, with gold surging to new highs, while more cyclical energy down significantly and industrial metals somewhere in the middle (Figure 5).

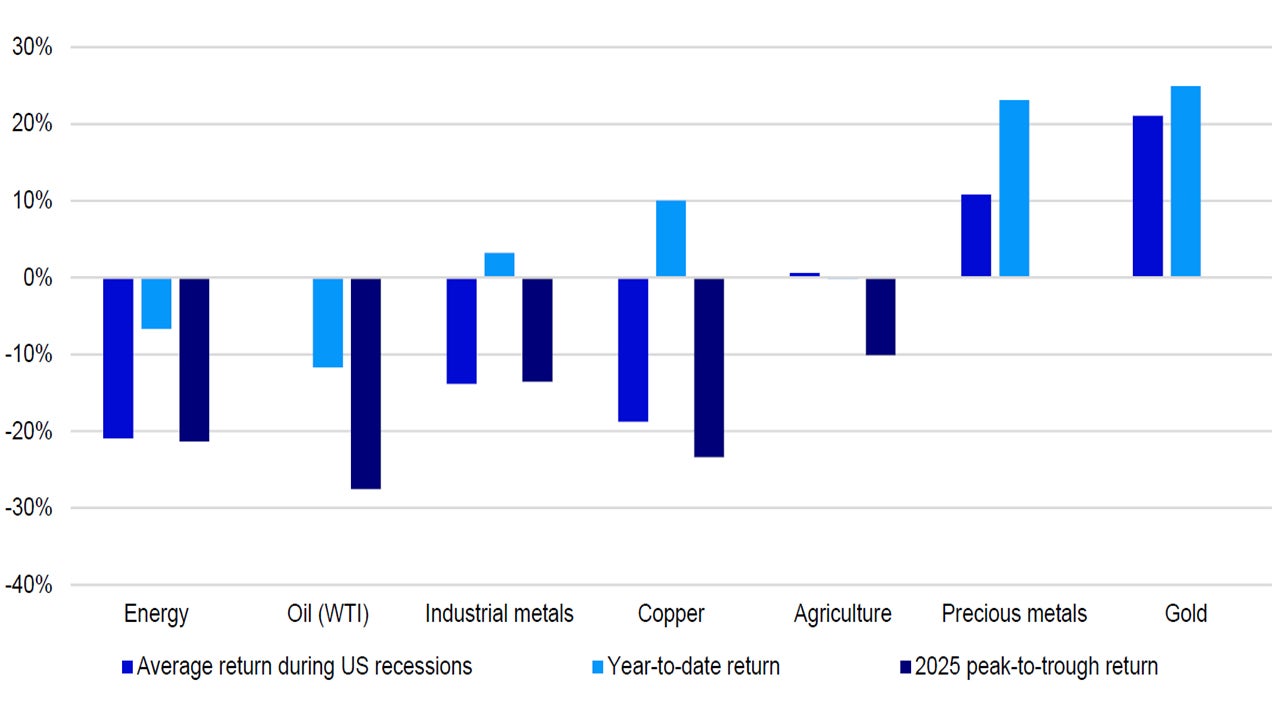

Although there has been a thawing of relations between the US and its major trading partners, some uncertainty remains. At the same time, even if tariffs settle at lower levels than the extreme “reciprocal” rates, they will still be above rates at the beginning of 2025. Thus, with a significant economic slowdown still potentially on the cards, we analysed commodity returns during US recessions since 1973, as defined by the National Bureau of Economic Research.

As would be expected, cyclical commodities tended to fall in these periods on average, while precious metals rose (Figure 2 – using S&P GSCI total return indices). However, just like every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way, there was a big dispersion of returns across recession episodes (see Figures 3 and 4). Although the precious metals index fell slightly in the early-1990s and 2020s, gold outperformed during all US recessions, as expected, while they both rose on average, by 11% and 21% respectively.

We do not have data for the industrial metals index in the 1970s, but it was the most consistent underperformer, falling by 14% on average in five of the other six recessions. Copper (using London Metal Exchange Grade A cash prices) performed even worse, falling by 19% on average including the early-1970s recession.

The oil crises that coincided with recessions in the early-1970s, around 1980 and the early-1990s make energy commodities perhaps a less reliable indicator, although they did fall in all the recessions from 2001 onwards, by around 43% on average. Although oil had close to 0% average returns during recessions, the average return was -29% if we exclude supply shocks (using West Texas Intermediate Cushing spot prices). The agricultural goods index has a similar profile with close to 0% overall returns on average.

Notes: Data as of 20 May 2025. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. See Figures 3 and 4 for the recession dates and detailed returns. Commodity index returns are based on S&P GSCI total returns indices for Energy, Industrial metals, Agriculture and Precious metals and we use the West Texas Intermediate Cushing Spot prices for crude oil, London Metal Exchange Grade A Cash for Copper and London Bullion Market prices for gold. Returns during US recessions are calculated between the first day of the month of the start of the recession to the first day of the month at the end.

Source: LSEG Datastream and Invesco Global Market Strategy Office

In my view, based on year-to-date returns, gold is the closest to pricing in a US recession, although geopolitical and debt concern have also boosted returns. All the other commodities came close to returns consistent with recessions in early-April using the difference between their year-to-date lows and highs. For example, energy commodities fell by 21% (oil 27.5%), industrial metals by 13.5% (copper by 15%) and agricultural commodities by 10%. It is important to mention, however, that oil prices were negatively impacted by the OPEC+ production increase around the “Liberation Day” tariff announcements. That may partly explain why oil remains 20% below its year-to-date peak and may have the most potential to gain from any upside surprise to growth.

At the same time, industrial metals, including copper, may be about 6% below their 2025 highs, but their year-to-date returns have been mildly positive. Hence, they could be vulnerable to a significant slowdown in US growth, while other large economies may struggle to compensate for that despite the stimulus flagged by Germany and positive signs in the traditionally capital-intensive Chinese economy.

Thus, our Overweight in industrial commodities in our Model Asset Allocation (Figure 8) and our Overweight allocation to the energy sector and Neutral allocation to basic resources in our Model Sector Allocation (Figure 9) would feel more comfortable if the global economy accelerates rather than decelerates.

Investment risks

The value of investments and any income will fluctuate (this may partly be the result of exchange rate fluctuations) and investors may not get back the full amount invested.