Applied philosophy: Are US corporate investment grade spreads unusually tight?

Corporate investment grade bonds in the United States are not necessarily the most exciting assets at this moment, but perhaps that is just as well (we are Neutral within our Model Asset Allocation). I generally view them as a defensive asset, thus I think that is a positive, not a negative. Nevertheless, despite some concerns over US economic growth, spreads have remained tight. Should investors be worried about that?

In a year dominated by the ins and outs of the tariff policy of the United States (US), we received a reminder in the last week that geopolitical risk has not diminished. After Israel attacked facilities in Iran linked to its nuclear programme, and Iran retaliated, financial markets reacted broadly as I would have expected with risk assets declining, while energy commodities and precious metals rallied on 13 June 2025. At the same time, fixed income assets were also slightly down on the day, apart from Chinese and Japanese government and corporate investment grade (in local currency terms). The situation has stabilised somewhat, though still feels fragile to me.

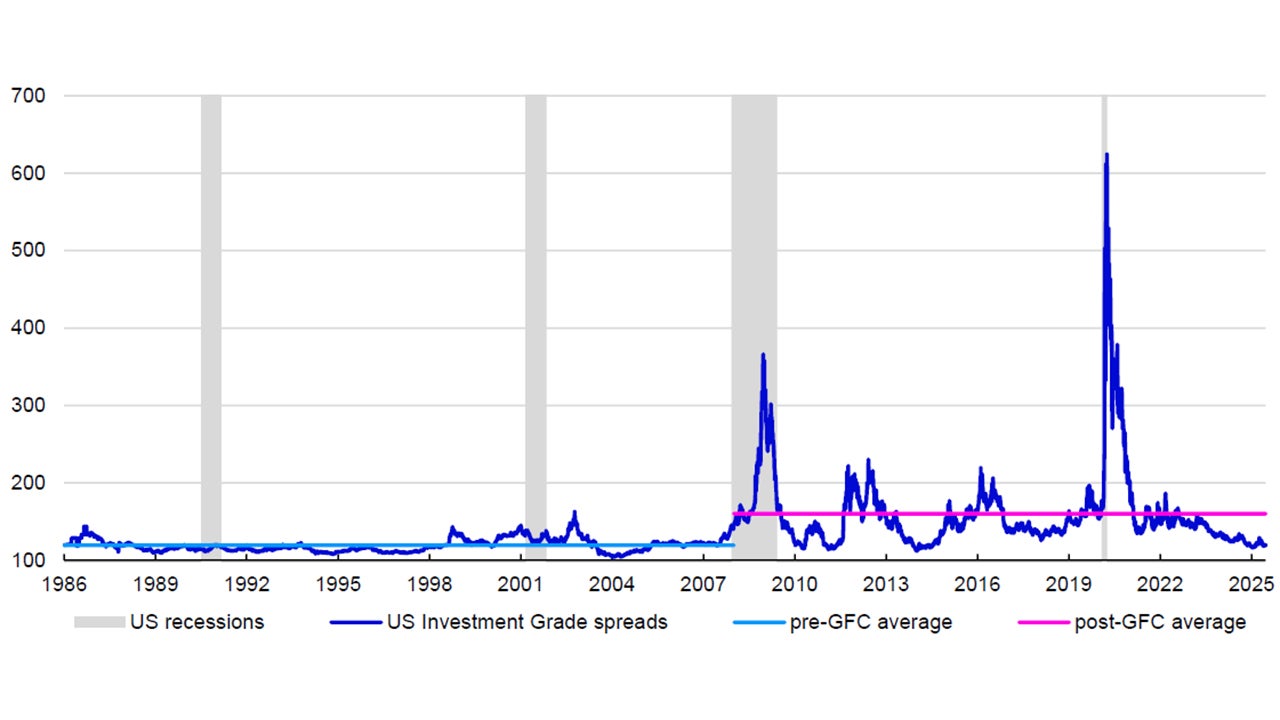

One of my concerns is that inflation may increase once again despite the lower-than-expected reading of US consumer price inflation (CPI) on 11 June 2025. The US has been perhaps the most prominent example of fixed income yields being pushed by opposing forces with concerns about the sustainability of their fiscal situation pulling yields higher, while worries about a potential economic slowdown have pushed them lower. This has resulted in the unusual situation where US government bonds have outperformed IG year-to-date despite macroeconomic indicators holding up (Figure 3), which may partly explain why spreads between yields on the two assets have remained close to cyclical tights (Figure 1). Should we be concerned about spreads widening significantly if the US economy slows as higher tariffs make their impact?

I have argued previously that the economic outlook we are facing may resemble the 1990s more than the 1980s or the 2010s (see here).I am not expecting similar GDP growth rates, but I think that US CPI inflation will remain within the “comfort zone” of the US Federal Reserve (Fed) even with the potential impact of higher tariffs. If policy uncertainty does not result in a deep recession, I think it is not unreasonable to expect the US economy to have similarly stable growth and interest rates during this cycle.

Even if we broaden our scope to the whole pre-Global Financial Crisis (GFC) era from 1 January 1986 (when our IG data starts) to 31 December 2007, the current spread of 119 basis points (bps) matches the full-period average (using the redemption yield on the Intercontinental Exchange (ICE) Bank of America (BofA) US Corporate Index minus the yield on the Datastream US Benchmark 10-year Government Bond Index, as of 20 June 2025). During that period, spreads only went above 150bps once – during the bursting of the “tech bubble” in 2002. Thus, current spreads look unusually low in the post-GFC era partly because we got used to 10-year Treasury yields being suppressed by Quantitative Easing (QE).

Notes: Data as of 20 June 2025. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Shaded areas recessions as defined by the National Bureau of Economic Research. We calculate spreads using the difference between redemption yields on the ICE Bank of America US Corporate Index and the Datastream US Benchmark 10-year Government Bond Index. We show daily data from 1 January 1986. Source: LSEG Datastream and Invesco Global Market Strategy Office

Nevertheless, I think there is more scope for spreads to widen than to tighten from this point (the low since January 1986 was 104bps). Although, even if we encountered a recession or a market shock, there is no obvious template we could follow to determine the magnitude of such moves. These could range from topping out at 120bps during the 1990 recession, through 220-230bps during the Eurozone crisis and the 2016 slowdown to 366bps during the GFC and 624bps during COVID. Assuming any economic slowdown driven by tariff-related uncertainty will be contained, either by offsetting fiscal easing (mostly tax cuts), or by the Fed cutting rates (if they look through a likely increase in inflation), I think spreads could remain near current levels, while yields are likely to fall consistent with the shallow recessions in 1990 and 2001.

The bigger concern, in my opinion is government bond yields rising from current levels, especially after falling following the intensification of the conflict between Israel and Iran (higher oil prices tend to pass through to headline US inflation quickly). I expect tariffs to be inflationary, as well, and therefore rates may stay near current levels in the near term. We may be over “peak tariffs”, but they are already higher than before 2025. At the same time, if high deficits persist, the fiscal situation could remain a source of upward pressure on Treasury yields. Indeed, this may lead to a perception, in my view, that the difference in the creditworthiness of the US government and corporate borrowers is narrower than in the past.

What is the most probable outlook for US corporate IG as an asset class? First of all, I assume that year-on-year US real GDP growth will recover towards its trend rate after a brief slowdown perhaps in H2 2025, so could be 1.5%-2% on average in the next 12 months and that CPI inflation will be close to the Fed’s target of 2%. This implies nominal GDP growth of around 3.5%-4%, which could allow the Fed to cut its target rate by around 100bps broadly in line with expectations implied by rate futures by mid-2026 (as of 20 June 2025). Over the medium term, assuming that spreads between 10-year Treasury yields and the Fed’s target rate will remain at a post-1980 average of around 100-120bps, this would suggest Treasury yields of around 4.5%, only slightly above the current 4.38% (as of 20 June 2025).

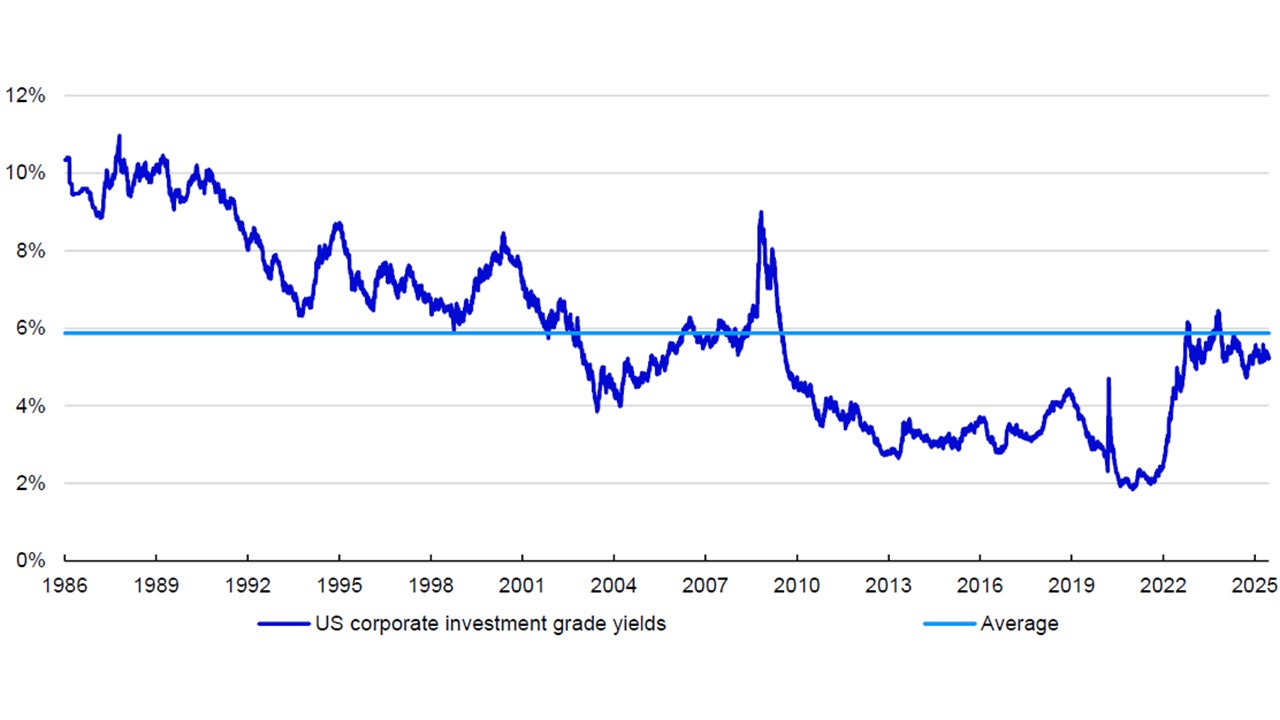

Without any significant change in spreads versus Treasuries, this implies slightly negative capital returns for US IG as yields would rise towards historical averages from the current 5.22% as shown in Figure 2 (as of 20 June 2025). This is consistent with our Neutral allocation in our most recent model asset allocation alongside other US fixed income assets (see here for the full detail).

Thus, I think there are better opportunities within the fixed income universe, especially in Emerging Markets (excluding China) both in government and corporate bonds where spreads look more attractive, and yields are higher in most markets. At the same time, if US dollar weakness persists, central banks in these markets could ease monetary policy without worrying about currency weakness, which could further boost potential EM returns.

Notes: Data as of 20 June 2025. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. We use daily data since 1 January 1986 showing the redemption yield on the Intercontinental Exchange Bank of America US Corporate Index.

Source: LSEG Datastream and Invesco Global Market Strategy Office

Investment risks

The value of investments and any income will fluctuate (this may partly be the result of exchange rate fluctuations) and investors may not get back the full amount invested.