Applied philosophy: How old is the captain?

US equities have been on a strong run, partly driven by multiples reaching levels only seen during extreme market events. At the same time, valuations in the rest of the world have remained close to or below long-term averages (apart from India, for example). We analyse the relationship between cyclically-adjusted price-to-earnings ratios and ten-year forward returns to compare potential regional returns.

Human beings tend to be good at creating narratives out of seemingly unconnected events. I am regularly asked to explain movements in financial markets and can certainly find stories that sound plausible ex-post. Of course, a bigger challenge is trying to predict what they will do in the future. Believers in the theories lying at the two extremes of a range between random walk theory and efficient market hypothesis probably do not feel they should try.

Philosophically, I am somewhere between the two, and this can still make it feel like I am trying to solve Gustave Flaubert’s famous riddle from 1841:

“A ship sails the ocean. It left Boston with a cargo of cotton. It grosses 200 tons. It is bound for Le Havre. The mainmast is broken, the cabin boy is on deck, there are 12 passengers aboard, the wind is blowing East-Northeast, the clock points to a quarter past three in the afternoon. It is the month of May. How old is the captain?”

Perhaps the most complex and fun exercise is trying to predict the future returns of equity markets, as far as I am concerned. Luckily, unlike in Flaubert’s riddle, I can rely on an anchor (pun fully intended): valuations. They may not be particularly useful in predicting short term returns, although there is a stronger relationship with long-term performance.

In January 2024, I analysed the relationship between the Shiller P/E and the US equity market and concluded that returns are likely to be below-average in the next ten years (see here for more). It also seems to work in the same way with a non-inflation-adjusted version of the cyclically-adjusted price-to-earnings (CAPE) ratio based on Datastream data, which can also be calculated for other markets.

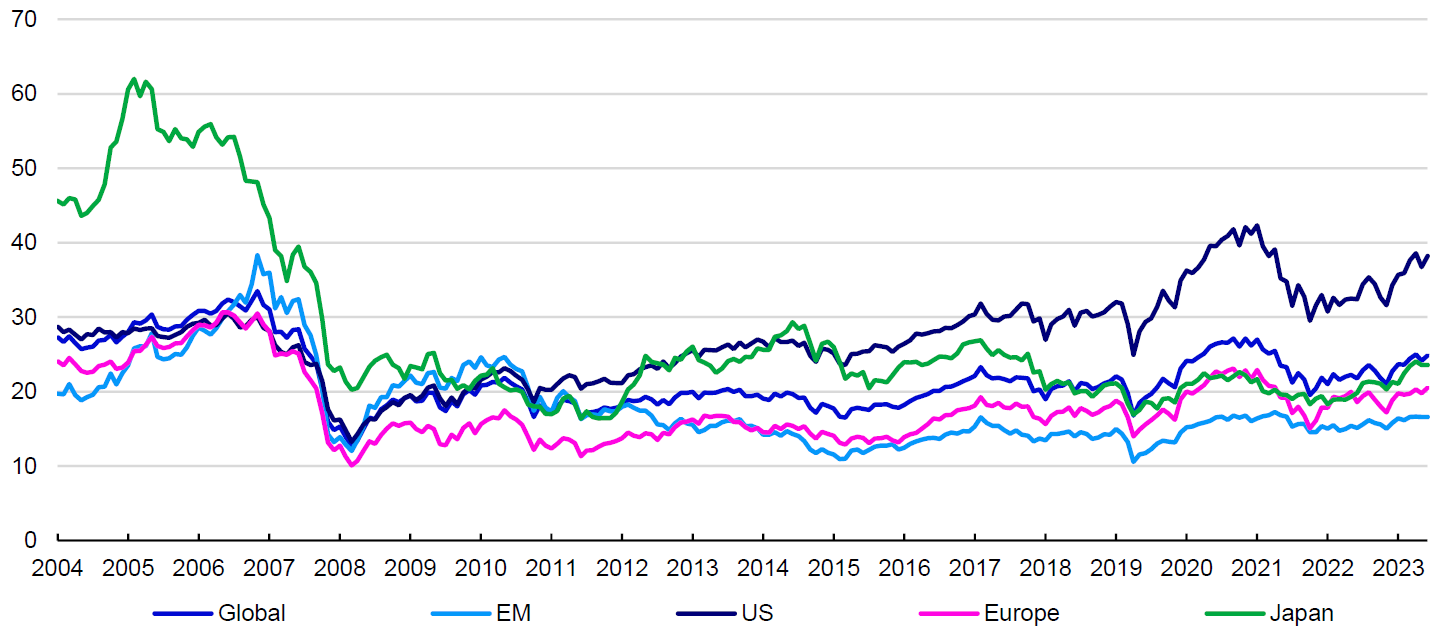

At the time, US equities looked expensive after strong returns mostly driven by mega-cap growth stocks (“The Magnificent Seven”, some of which do not look so magnificent now). If anything, the US has become even more expensive: the CAPE rose from 35.7x at the end of 2023 to 38.2x as of 31 May 2024. As Figure 1 shows, it was not alone. CAPE ratios rose in all regions year-to-date, which is not unusual in market expansions. Prices can move faster than earnings (especially if we use their ten-year average).

Nevertheless, the outperformance and decoupling of US equities is evident and shows little sign of coming to an end. Despite a narrowing spread of equity returns year-to-date (in local currency terms, see Figure 4), the valuation gap has not diminished. Assuming valuations can be a useful guide to future returns, what does that imply for each region?

Notes: Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Data as of 31 May 2024. We use Datastream Total Market indices. Cyclically-adjusted price-to-earnings ratios use a ten-year average of earnings based on monthly data between 31 December 2004 and 31 May 2024. Source: LSEG Datastream and Invesco Global Market Strategy Office

Unfortunately, the relationship between CAPE ratios and ten-year future returns is not uniform. Based on their respective r-squared values, there is a wide spread of how strong the predictive power of a region’s CAPE ratio is. The US has the highest r-squared ratio of 0.78, followed by Japan with 0.57 and Emerging Markets (EM) with 0.30, while the relationship is the weakest in Europe with an r-squared of 0.18 (all calculations use daily data between 3 January 1983 and 31 May 2014, except for EM, where the data series starts on 30 December 2004). Splitting Europe into Europe ex-UK and UK does not improve the r-squared values (they are 0.13 and 0.03 respectively). At the same time, those of the Chinese (0.54) and Indian (0.68) markets are higher than the 0.31 for EM. Perhaps exchange rate movements play a role in loosening the relationship for multi-currency indices (and also for a market such as the UK, where the majority of earnings are derived from overseas).

Nevertheless, using the equation produced by a simple regression between the CAPE ratios and ten-year forward returns, current valuations imply that the US faces the lowest annualised capital returns in the next decade at 2%, while Europe ex-UK may potentially have the highest annualised returns at 7.1%. In between are China and Europe (including UK stocks) at around 6%, followed by the UK at 5.6%, Japan at 5.4% and India at 4.9% (all are annualised capital returns in local currency, except for Europe ex-UK and Europe, which are in USD). Based on long-term average dividend yields, this would provide attractive annualised total returns of around 9.5% for European equities (UK returns would be similar, while Europe ex-UK would be higher at 10%), just under 8% for China and around 7% for Japan. Indian total returns would be lower at 6.3%, while US returns would be among the lowest at approximately 4.8%.

Intuitively, this seems like a plausible outcome to me, although there are many variables at play (calculating the captain’s age is not easy). While I do not necessarily have to take into account where we are in the economic cycle (the advantage of using 10-year average earnings), I must attempt to judge structural forces. Most importantly, whether we are in the relatively high growth environment of the pre-GFC period, or the “secular stagnation” of the 2010s. A return to pre-GFC growth rates and policy settings would require a rise in productivity growth, especially given the decline in population growth (perhaps provided by applications for generative artificial intelligence), which seems a long shot to me at this moment. At the same time, I think a return to the immediate post-GFC economic environment is unlikely in the short term unless governments decide on large-scale austerity (corporate leverage seems less of an issue).

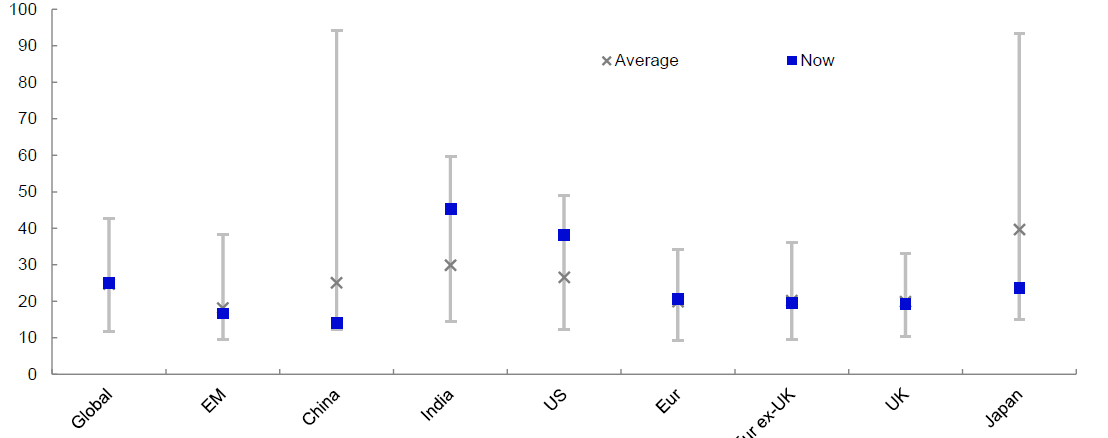

Assuming that these returns are not far off the mark, they look attractive versus government bonds almost everywhere over the next decade, except the US. The exceptional run in US equities partly driven by multiple expansion may be running out of road, especially if interest rates stay relatively elevated, in my view. This environment may favour markets more exposed to value. Therefore, within equities, I would favour markets with lower valuations (see Figure 2), such as Europe and Emerging Markets over the US and India in the next ten years, with Japan somewhere in between.

Notes: Data as of 31 May 2024. We use Datastream Total Market indices. Cyclically-adjusted price-to-earnings ratios use a ten-year average of earnings based on daily data between 1 January 1983 and 31 May 2024 (except for China from 1 April 2004, India from 31 December 1999 and EM from 3 January 2005).

Source: LSEG Datastream and Invesco Global Market Strategy Office