Applied philosophy: Strategist from East of the Elbe

Eastern members of the European Union have suffered a broad economic slowdown in 2023 after a post-pandemic bounce in 2021 and 2022. We believe the deceleration was mostly driven by shrinking real disposable incomes but, as inflation ebbs, we expect a reacceleration, especially if the global economy avoids a deep recession. We think this will allow for a less restrictive policy mix, which, alongside attractive valuations, should support regional government bonds and equities.

The Elbe has been a dividing line in Europe for millennia, separating the “East” from the “West”. Due to its size and financial heft, we tend to pay more attention to the West. However, we believe it is worth looking outside our comfort zone and widening our perspective. With that in mind, we are starting what could become a regular series focusing on Eastern members of the European Union: Bulgaria, Croatia, Czechia, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia. The main question we will attempt to answer is how to allocate among countries in the region across equities and government bonds.

First, it is tough out there. The post-pandemic bounce in economic growth has given way to a broad-based slowdown as commodity prices rose and financial conditions tightened, especially throughout 2022. Although we expect the impact of these to fade, they are still being felt, especially as wages have not completely caught up with prices, thus constraining consumer spending. On the other hand, we expect the impact of tighter monetary policy to fade as we approach 2024, and domestic pressures to ease.

However, we think that a slowdown in developed market growth could push the global economy close to a recession before a recovery starts in 2024, which implies sluggish export growth at best for Eastern European countries.

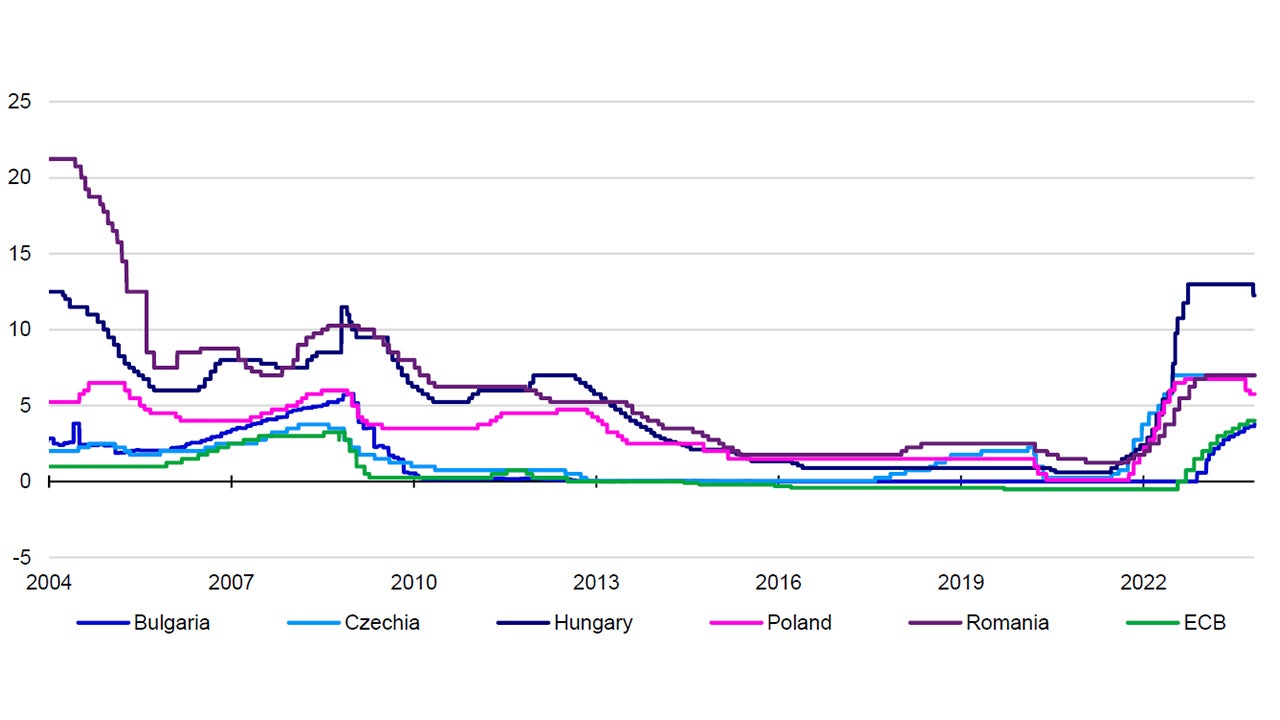

The monetary tightening cycles of the four countries outside the Eurozone or the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (Czechia, Hungary, Poland and Romania) started ahead of developed markets, thus we think most of the impact of higher interest rates may have passed. As far as the rest of the region is concerned, it may take time for the interest rate increases by the European Central Bank (ECB) to work their way through the real economy (including their main trading partners within the Eurozone).

We think the ECB is probably at the end of its tightening cycle and expect rates to fall from current levels in the next 12 months. In our view, falling inflation will also allow non-euro member central banks to reduce rates in the next year. The Polish central bank was the first in the region to cut rates on 7 September by 75 basis points (see Figure 1), which surprised markets, especially as annual inflation remained in double-digits in August. Nevertheless, even if this move proves premature, we think it may be the start of a turn in the monetary policy cycle (Poland cut by another 25bps on 4 October followed by a 75bps cut in Hungary on 24 October).

Notes: Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Data as of 31 October 2023. Using daily data from 1 January 2004.

Source: LSEG Datastream and Invesco Global Market Strategy Office

Of course, this assumes inflation continues to fall as it has done since peaking in autumn 2022. The main outlier is Hungary, where inflation peaked later and remains significantly higher than the rest of the region. Unfortunately, the situation may get worse before it gets better. First, base effects will fade as we progress through the autumn. Second, increasing energy prices may also temporarily raise headline inflation (as in other countries).

What makes the current macroeconomic environment even more complex is the potentially antithetical policy mix in Eastern EU members. Although we expect monetary policy to be less restrictive, significant easing is unlikely, in our view, especially if inflation remains higher than policy targets. At the same time, escalating debt servicing costs may require tighter fiscal policy, which implies less support for local economies especially in countries more reliant on government spending, such as Croatia, Hungary and Poland. That will be partly mitigated by generous EU funding that amounts to 3-5% of GDP annually in most of the countries in our universe.

The good news is that the political landscape will probably remain stable in 2024 (European Parliament elections are usually a minor event). After two elections produced contrasting results in October in Slovakia and Poland there is limited potential for an upset. Although a lot can change before the voting commences in general elections in Croatia and Lithuania (in the spring) and in Romania (autumn), we think that economic policy is likely to be largely unchanged, especially in Croatia and Lithuania both of which are members of the Euro Area.

Even in Romania, where right-wing populist parties seem to be in the ascendant, they will most probably need to form a coalition government, reducing the likelihood of abrupt policy changes. The same applies to Slovakia, where the populist SMER-SSD received the mandate to lead a coalition, but whose room for manoeuvre will be constrained by EU fiscal rules and euro membership requirements. Finally, the sigh of relief markets breathed after the success of the opposition alliance in Poland reflects the potential for market and EU-friendly policies and a return to the European mainstream leaving Hungary increasingly isolated.

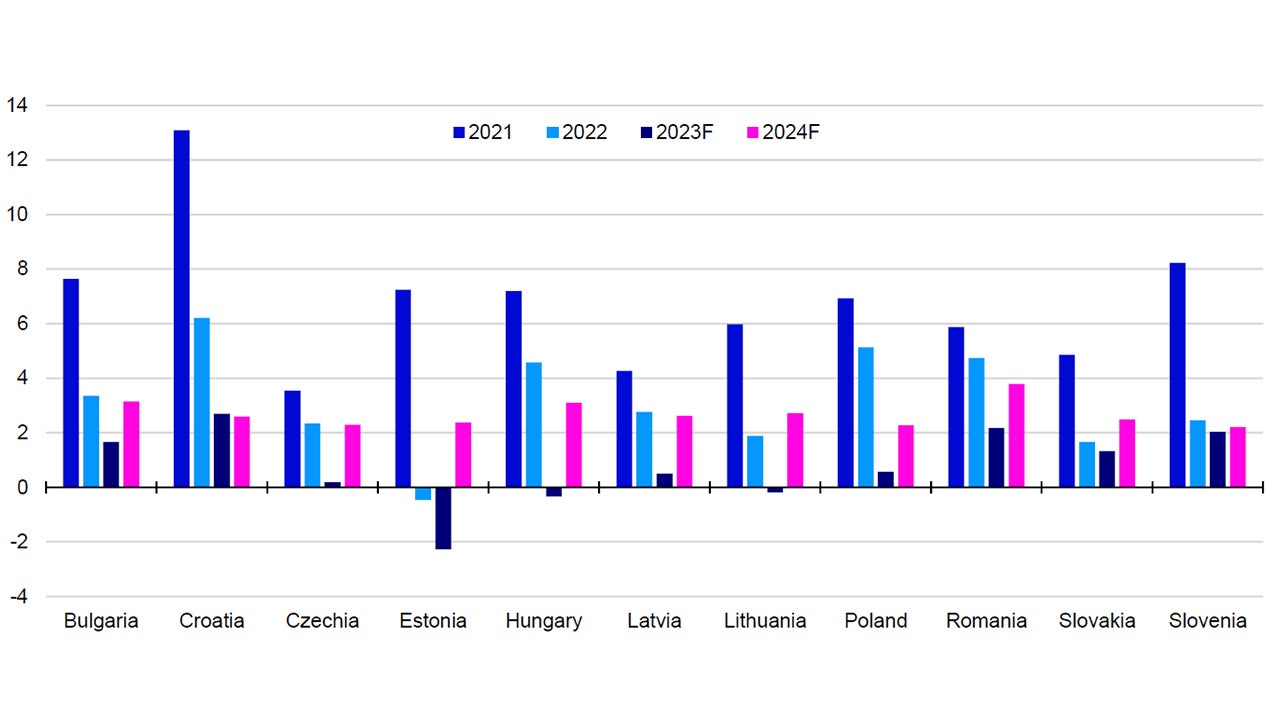

Thus, the macro backdrop appears similar to our broader global outlook of moderating growth and inflation with a turn in the monetary policy cycle (our view is broadly consistent with forecasts by the International Monetary Fund shown in Figure 2). Within a generally cautious stance, we have been Overweight Emerging Markets equities and sovereign debt in our model asset allocation as a hedge in case the global economy performs better than we expect (Figure 6).

What does this imply for markets? The main question in our view is whether a potential slowdown in global economic growth or the relief from falling inflation will matter more? We envisage a “year of two halves”: a potentially volatile period in the next one or two quarters, followed by a return of “animal spirits” in the spring and summer.

Notes: Data as of 31 October 2023. We use historical data for 2021 and 2022 and forecasts by the International Monetary Fund for 2023 and 2024.

Source: LSEG Datastream, International Monetary Fund, Invesco Global Market Strategy Office

This calls for a balanced approach, in our view, with a focus on valuations as long as sentiment remains fragile. We view government bonds as defensive assets for developed market issuers, but not so for these countries in a global asset allocation context. However, in our view, the prospect of gradual easing of monetary policy implies lower yields in the next 12 months.

As we expect this easing to come before those in developed markets, exchange rate movements could limit positive returns from CEE assets for those countries outside the euro area and the ERM. Within that exclusive group, Hungary appears the most vulnerable as the outlier both in terms of the likely path of its inflation (remaining higher than the rest of region) and the spread between its central bank target rate versus those of major developed markets (especially assuming larger rate cuts by the Hungarian central bank, the MNB, than the ECB, for example). Czechia, Poland and Romania are likely to face a smaller headwind in this respect.

This also applies to equities, although we view the relationship as more complicated. Being open economies, currency weakness contributes to higher profits (up to a point). The major risks for both asset classes are an escalation of geopolitical conflicts and a deep economic slowdown (perhaps triggered by adverse events). These would likely cause a “flight to safety”, which would potentially result in negative returns.

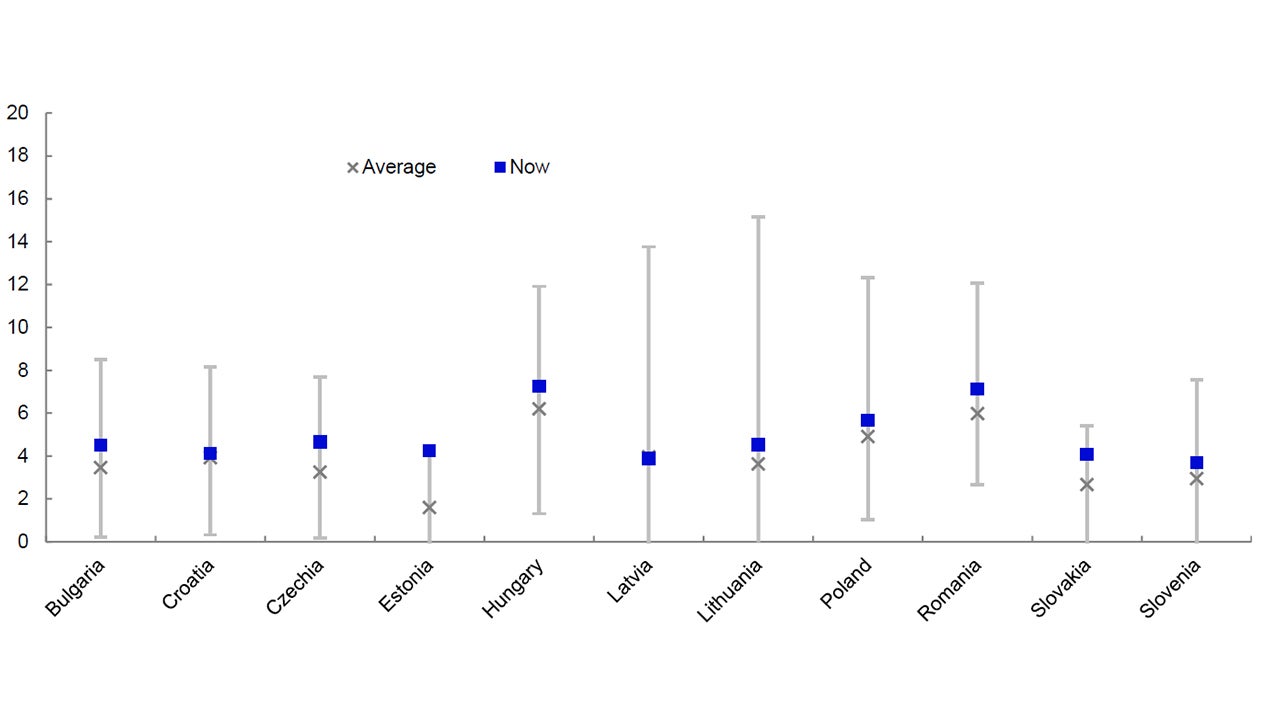

For the moment, we view these as tail risks and we are positive on CEE government bonds. As Figure 3 shows, in absolute terms, the yields of Hungary and Romania are the highest (as of 31 October 2023). Although they are significantly below the 9.2% yield on the broader Emerging Markets universe (based on the Bloomberg Aggregate Sovereign Bond Index as of 31 October 2023) perhaps due to their structurally lower inflation and interest rate expectations.

However, in Hungary’s case the threat of losing EU funds and lack of fiscal discipline may require higher yields to compensate for the risks, especially if stubbornly high inflation require higher rates than elsewhere in the region. Also, when compared to their respective historical averages, the yields of both countries are only 70-100 basis points higher.

We think there are better opportunities, especially with regards to Poland, where the reintroduction to the European mainstream may reduce the risk premium versus core Eurozone yields. At the same time, the yields of Czechia and Slovakia look the most attractive compared to historical averages (roughly 120 basis points higher). These markets also look attractive relative to Bunds with their spreads 90 and 45 basis points above historical averages. They are also both below Italy’s implying perhaps a lower risk premium due to their lower debt levels.

Notes: Past performance is no guarantee of future returns. Data as of 31 October 2023. Historical ranges and averages include daily data from 14 April 2006 for Bulgaria, 30 January 2008 for Croatia, 1 May 2000 for Czechia, 1 February 1999 for Hungary, 15 April 2003 for Lithuania, 1 January 2001 for Poland, 16 August 2007 for Romania, 7 January 2004 for Slovakia and 3 April 2007 for Slovenia. Historical ranges and averages include monthly data from 30 June 2020 to 30 September 2023 for Estonia and from 31 January 2001 to 30 September 2023 for Latvia. We use Refinitiv Government Benchmark 10-year bond indices for Bulgaria, Croatia, Lithuania, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia. We use Datastream benchmark 10-year government bond indices for Czechia, Hungary and Poland. We use OECD 10-year government bond yields for Estonia and Latvia.

Source: LSEG Datastream and Invesco Global Market Strategy Office

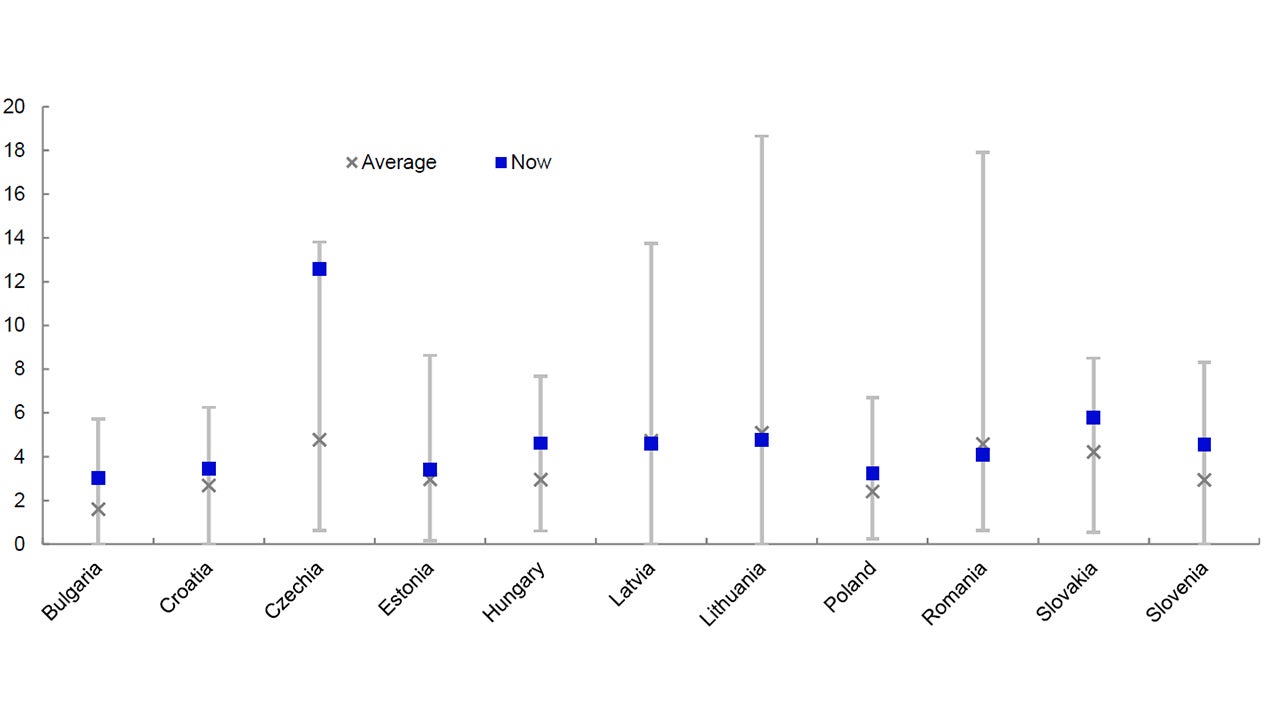

Notes: Past performance is no guarantee of future returns. Data as of 31 October 2023. Based on daily data using Datastream Total Market indices. Historical ranges and averages include daily data from 2 October 2000 for Bulgaria, 3 October 2005 for Croatia, 27 January 1994 for Czechia, 5 June 1997 for Estonia, 21 June 1991 for Hungary, 3 November 1997 for Latvia, 1 April 1998 for Lithuania, 1 March 1994 for Poland, 29 December 1997 for Romania, 1 March 2006 for Slovakia and 31 December 1998 for Slovenia.

Source: LSEG Datastream and Invesco Global Market Strategy Office

We expect healthy equity returns in the region based on our assumption of a global economic recovery in the second half of 2024. Exposure to CEE markets also offers higher yields in absolute terms than the 3.4% of the broader EM universe (using Datastream Total Market indices as of 31 October 2023). Only Bulgaria and Poland have lower yields than that, while in our view, Hungary and Slovenia appear to be in the sweet spot of having dividend yields well-above historical norms and relative to their peers in the region (Figure 4). On the other hand, despite appearing to offer the highest dividend yield, we would be cautious with regards to Czechia where only one stock is responsible for most of that yield. Nevertheless, we think that equity returns will be more muted until there is more clarity on where the global economy is heading, which we expect to happen in H1 2024.