Applied philosophy: The red and the blue

Chinese sovereign bonds have outperformed US Treasuries since the middle of 2020. An earlier reopening and more generous fiscal and monetary easing boosted consumer spending in the US and added to inflationary pressures triggering a sharp rise in yields. Meanwhile, longer lockdowns in China and less generous support kept yields there in check. We think that our base case of an end to rate rises in the US and a re-synchronisation of economic growth imply an outperformance of Treasuries over the next 12 months.

Both China and the US have defied our expectations of the path they would take in 2023. We thought the US economy would struggle with one of the sharpest rate hiking cycles ever, but it has been motoring on boosted by excess savings accumulated during COVID-19 lockdowns. At the same time, we expected the Chinese economy to boom after its official reopening and pent-up demand to fuel consumer spending, but that has not been the case so far (relative to its pre-COVID pace).

The latest retail sales figures seem to highlight a divergence in the two largest economies of the world. The US number surprised on the upside and after a brief wobble in Q2 2023, returned to its pre-pandemic rate of growth around 3% year-on-year. The Chinese figure at 2.5% year-on-year, however, was lower than both the Reuters consensus estimate at the time and well below the pre-pandemic trend of double-digit growth rates, while it is also lower than the corresponding figure in the US (although the US figure is boosted by higher inflation, as both are in nominal terms).

On the other hand, industrial production has been weak in both economies this year (as highlighted by July’s figures), consistent with negative sentiment in surveys of purchasing managers. Although Chinese output growth is positive year-on-year, that is nowhere near pre-COVID rates (similar to retail sales). Weakness is also evident in the US, where year-on-year industrial output growth has been hovering around 0% year-to-date.

It is hard to say which indicator is a better reflection of the overall economic performance of these countries at this stage. Although Chinese GDP growth in Q2 2023 was above the official target of 5% (which was lower than in previous years), further weakness in consumer spending could make reaching that target more challenging. US GDP growth in Q2 2023 of 2.6% year-on-year suggests an economy perhaps inching closer to the “soft landing” the Federal Reserve (Fed) hopes for, and a strong start to Q3 – based on retail sales growth – bodes well for the short term, in our view.

Part of the answer why both economies have surprised us and how to view their prospects for growth lies in their approach to handling the pandemic, in our opinion. Support in the US was not only generous, but also reached consumers directly during the initial lockdowns. On the other hand, Chinese lockdowns were more stringent and longer lasting, but the rapid response kept the virus more contained requiring less fiscal support. This meant that the resulting decline in GDP was somewhat smaller in China than the US, and therefore it is perhaps no surprise that the rebound is also less sharp (US consumers also accumulated more in excess savings).

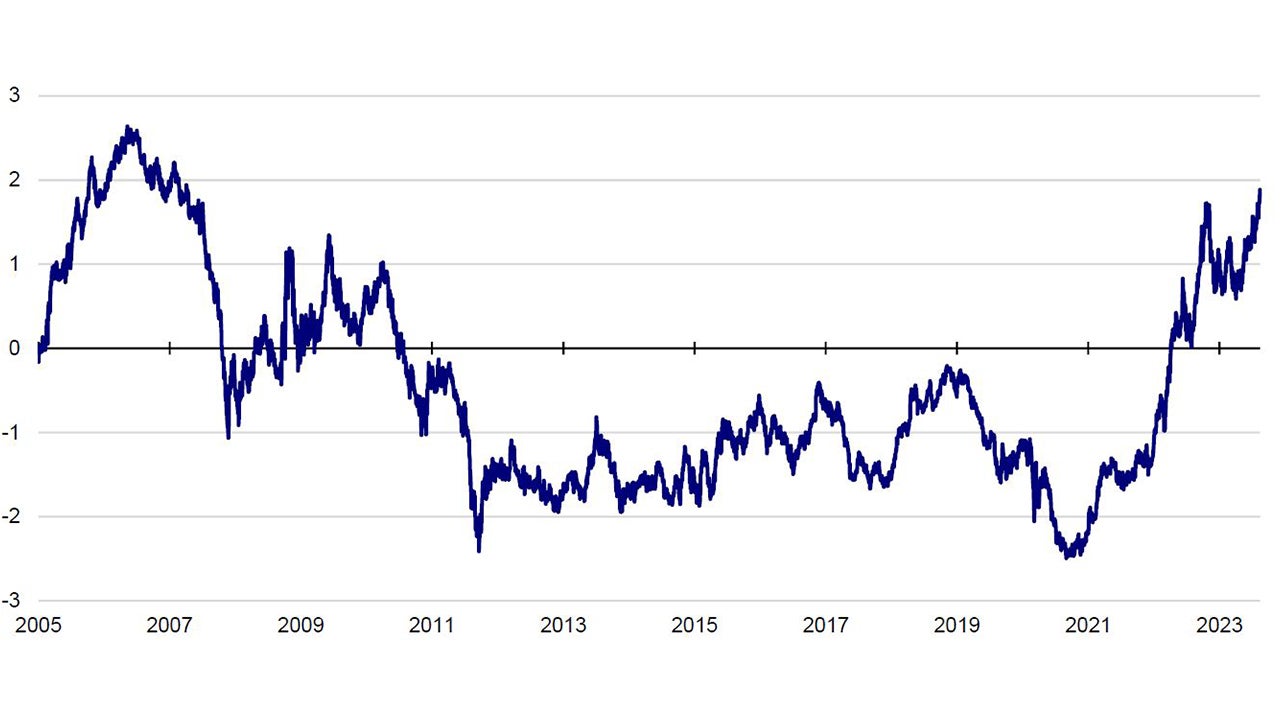

Notes: Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Data as of 17 August 2023. All indices use daily data from 3 January 2005 to 17 August 2023. The China government bond yield series shows the yield-to-maturity of the ICE BofA China Government Index. The US 10-year Treasury yield shows the Datastream benchmark 10-year Treasury yield. We calculate the relative total returns by dividing the ICE BofA China local currency government index by the Datastream benchmark US Treasury index rebased to 100 on 3 January 2005.

Source: Refinitiv Datastream, Intercontinental Exchange, Invesco

At the same time, US monetary policy became extremely loose, while the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) cut its main policy rate only slightly during 2020 and 2021. Even its other important policy tool, the reserve requirement ratio was cut by only one percentage point between the start of 2020 and the end of 2021. The looser policy in the US (both fiscal and monetary) has required a harsher reset, but the effect on consumer spending from this was offset by excess savings, while China retained its capacity to react to any slowdown in growth, even if any loosening in 2023 so far has had minimal visible impact on the economy.

The way these economies perform has big implications for their respective sovereign bond markets and their returns relative to each other, in our view. We have identified five broad periods since the end of 2004 in their relative returns (see Figure 1): 1) Chinese outperformance from the beginning of 2005 to March 2006 during late-stage tightening in the US and falling bond yields in China; 2) US outperformance from March 2006 to September 2011 around the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) when the US introduced several rounds of Quantitative Easing, while China increased interest rates in 2010-2011 (partly to offset a big fiscal boost); 3) Chinese outperformance from September 2011 to November 2018 driven by higher Chinese bond yields; 4) US outperformance from November 2018 to September 2020 in a period of global economic slowdown and US yields falling faster than those of China; 5) Chinese outperformance since September 2020 as yields in the two markets have moved in opposite directions reinforced by monetary tightening in the US and cautious loosening in China.

Can this period of Chinese outperformance continue? To a certain extent the current environment is unprecedented. For the first time in the last 20 years, the Fed’s main policy rate is higher than that of the PBoC (the 1-year loan prime rate). Also, the spread between US Treasury yields and Chinese government bonds has not been this wide since before the GFC (Figure 2). If we accept the view that starting yields determine long-term returns, this seems to signal that a reversal of fortunes may be on the cards.

However, there are risks to this view in the short term mainly stemming from a potential divergence in economic performance. If US economic growth reaccelerates (with perhaps a corresponding rise in inflation), while the Chinese economy continues to underperform, this could imply further outperformance by Chinese bonds.

The opposite of that (US slowdown, Chinese reacceleration) would likely mean rising yields in China and falling US yields, in our opinion. Our base case, however, is that the US will re-synchronise with the rest of the world and that its growth will slow before recovering again. That could allow the Fed to signal its willingness to first stop and then partially reverse its monetary tightening. At the same time, we think it unlikely that the PBoC will start rapidly loosening policy despite its larger potential toolkit to counteract economic weakness (mindful that it will boost the property sector that it is determined to de-risk). Finally, higher starting yields in the US could allow a period of outperformance even if Chinese yields fell at the same time. Thus, at this point, our preference is for US Treasuries versus Chinese sovereign debt over the next 12 months.

Notes: Past performance is no guarantee of future returns. Data as of 17 August 2023. We use daily data from 3 January 2005 to 17 August 2023. The spread shown is the difference between the Datastream benchmark 10-year Treasury yield and the yield-to-maturity of the ICE BofA China Government Index.

Source: Refinitiv Datastream and Invesco