Applied philosophy: Where do we find value in emerging market equities in 2024?

The recovery from the global equity bear market of 2022 has been on pause for Emerging Market stock markets since the middle of last year. On paper, the region could find the economic and policy environment of 2024 hospitable, especially if the global economy gets through its current soft patch and developed market central banks start cutting rates. In such a diverse region, we think it is worth digging deeper into which countries we would favour for the long term based on their valuations.

During this unseasonably warm February, I find myself thinking increasingly about what the world was like when I was a child. In those days, we still had four easily distinguishable seasons in Continental Europe. February was firmly a winter month, and I could expect to be able to build a lump of snow in the garden that I euphemistically called a snowman. February in London this year feels more like how I remember the end of March. Has spring begun early or will winter return?

Equity markets have reflected the optimism of spring year-to-date. However, this positivity has not been uniform. Emerging Markets (EM) have been unable to keep pace with their developed market counterparts, especially the United States, where large technology firms reaped the rewards of higher valuations and earnings driven by excitement around artificial intelligence. On the surface, this should not be surprising: receding hopes of developed market interest rate cuts, a relatively strong US dollar and a decelerating global economy may not have favoured risk assets in EM.

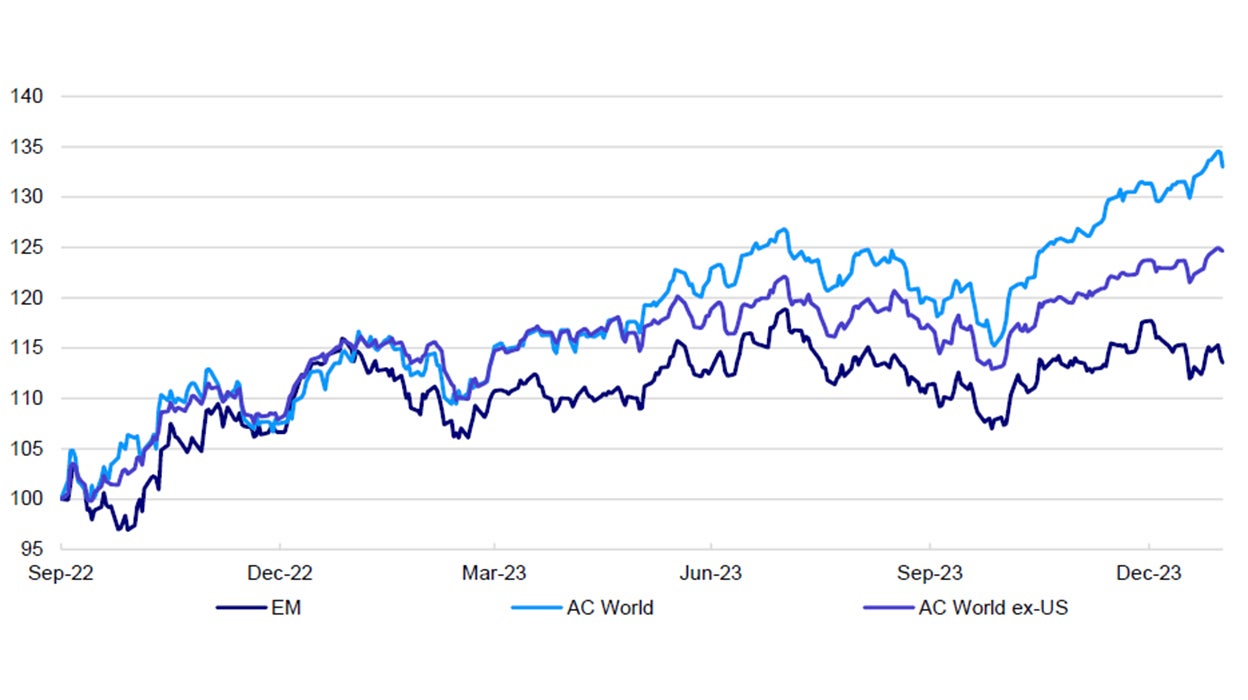

The last time we did a deep dive into EM equity valuations in September 2022, We marvelled at their resilience during a bear market. However, their recovery from that bear market has been less spectacular than for developed market stocks, registering about 12% total returns in local currency since the end of September 2022 vs 33% on the MSCI All-Country World Index and 25% on the MSCI All-Country excluding the US (Figure 1).

This divergence of returns highlights the difference in how the two largest economies in the World recovered after pandemic-era restrictions and their respective policy settings. Stricter controls in China during parts of 2020-2022 were coupled with less fiscal and monetary easing, while developed markets had fewer restrictions and more support (especially the US). Nevertheless, the Chinese economy fared relatively well, and we viewed the underwhelming recovery in China during 2023 partly as a function of a shallower dip in activity compared to the US and Europe, for example.

One of the reasons why the US economy outperformed expectations in 2023 was the large amount of “excess savings” built up during that period of extraordinary support. At the same time, the return of the economy to its pre-pandemic state of being driven by services consumption boosted domestic providers to the detriment of many export-oriented EM economies. Therefore, economic fundamentals may at least partly explain the underperformance of EM equities. As this dislocation fades out of view, how will this diverse group fare in 2024?

Notes: Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Data as of 31 January 2024. We show daily data from 30 September 2022 rebased to 100 on that date. We use the local currency versions of total return indices for the MSCI Emerging Markets Index, the MSCI All-Country World Index and the MSCI All-Country World ex-US Index.

Source: LSEG Datastream, MSCI, Invesco Global Market Strategy Office

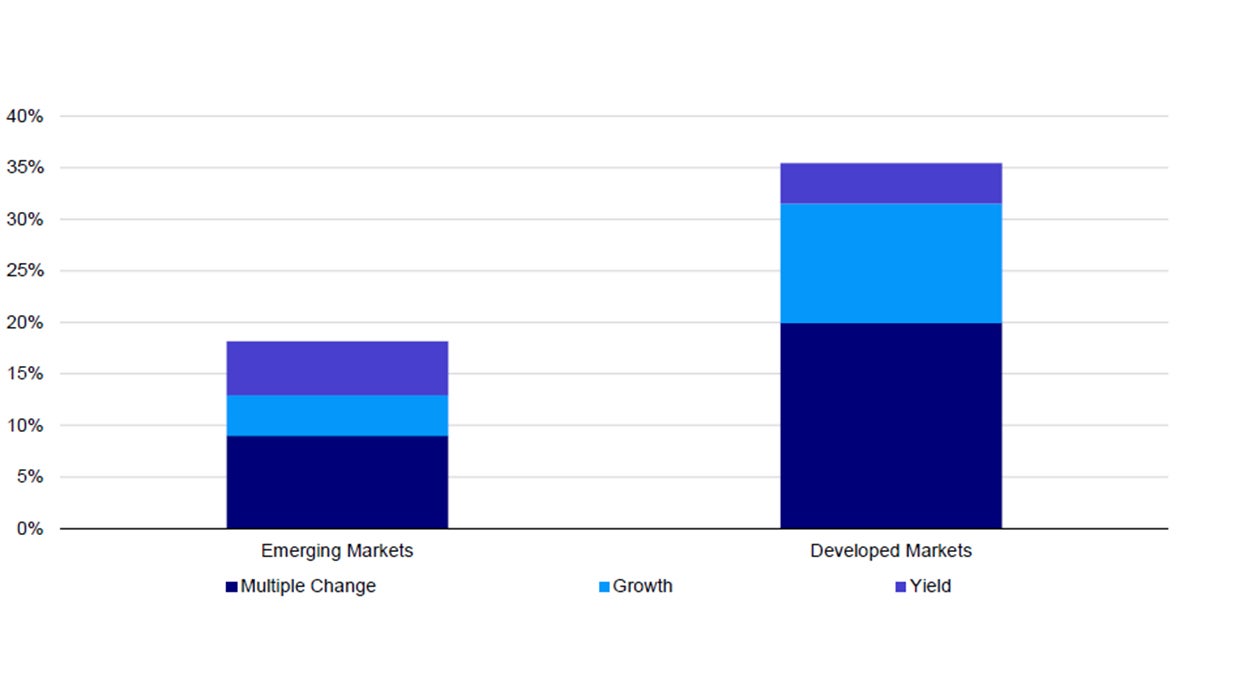

A good way to start, in our opinion, is to examine what drove this performance differential. If we decompose returns into the change in valuations (using dividend yields), dividend growth and income, it becomes evident that developed market (DM) dividends not only grew faster between 30 September 2022 and 31 January 2024, but valuations also expanded (see Figure 2). EM equities may have had higher yields both at the beginning and the end of the period, but that was overshadowed by higher capital returns in DM in aggregate.

We can think of at least three reasons why that might have happened: 1) a fading belief in the power of EM economies to catch-up with DM (especially the US), 2) the widening gap between the two groups of countries in terms of technological progress (most of the multiple expansion was driven by the technology sector), 3) expectations of a monetary policy pivot favouring long duration DM assets (DM equities have a higher weighting in such sectors).

Thus, the valuation discount that opened up during the COVID-19 pandemic widened further making an even stronger case for EM equities for contrarians, like us. Whether the main drivers of that are structural or cyclical could be up for debate, although we suspect cyclical factors will have a bigger impact in the next 12 months (structural change takes a longer time to unfold, in our view).

We think our base case for 2024 implies a positive environment for EM (see here for the full detail). A weakening US dollar, falling developed market interest rates and a potential rebound in economic growth in the second half of the year could boost returns on EM equities. On top of that, valuations have priced in a lot of bad news. The dividend yield of 3.2% is higher than for all other regions apart from the UK’s 3.7%, and its cyclically-adjusted price/earnings ratio (CAPE) of 16.2x is the lowest (all valuation ratios are as of 31 January 2024). EM equity valuations also look favourable compared to historical averages: they trade at a 20% discount based on dividend yield and a 21% discount on CAPE.

As the monetary policy cycle turns, we expect cyclical pressures to fade after the global economy gets through some near-term weakness. Equity markets may start to anticipate that, which may favour the more cyclical regions and sectors. The current disinflationary process also remains well-established, in our view. Indeed, EM central banks have already started reducing interest rates boosting local markets in Hungary and Poland, for example.

We are also positive about the long-term prospects of EM despite short term challenges and perhaps we may even experience a new “super-cycle” of outperformance. We think valuations should support EM equities even in the event of a global recession. Eventually (we think) the current period of uncertainty will pass and improving risk appetite could boost EM returns. Moderating commodity prices can also ease the “cost of living crisis” in countries with significant imports (though may be penalise commodity producers). In the long term, demographic momentum may help India and Indonesia (along with Africa) take over as the engines of growth.

Notes: Data as of 31 January 2024. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Returns are calculated between 30 September 2022 and 31 January 2024. “Yield” shows the income investors received from dividends paid during the period concerned. “Growth” shows the rate of dividend growth, calculated using the percentage change in dividend per share (DPS) values for the sector indices. DPS is calculated as dividend yield times the price index. “Multiple Change” refers to the change in dividend yield, plus the change in dividend yield times dividend growth. We use the Datastream Total Market Emerging Market and Developed Market indices.

Source: LSEG Datastream and Invesco Global Market Strategy Office

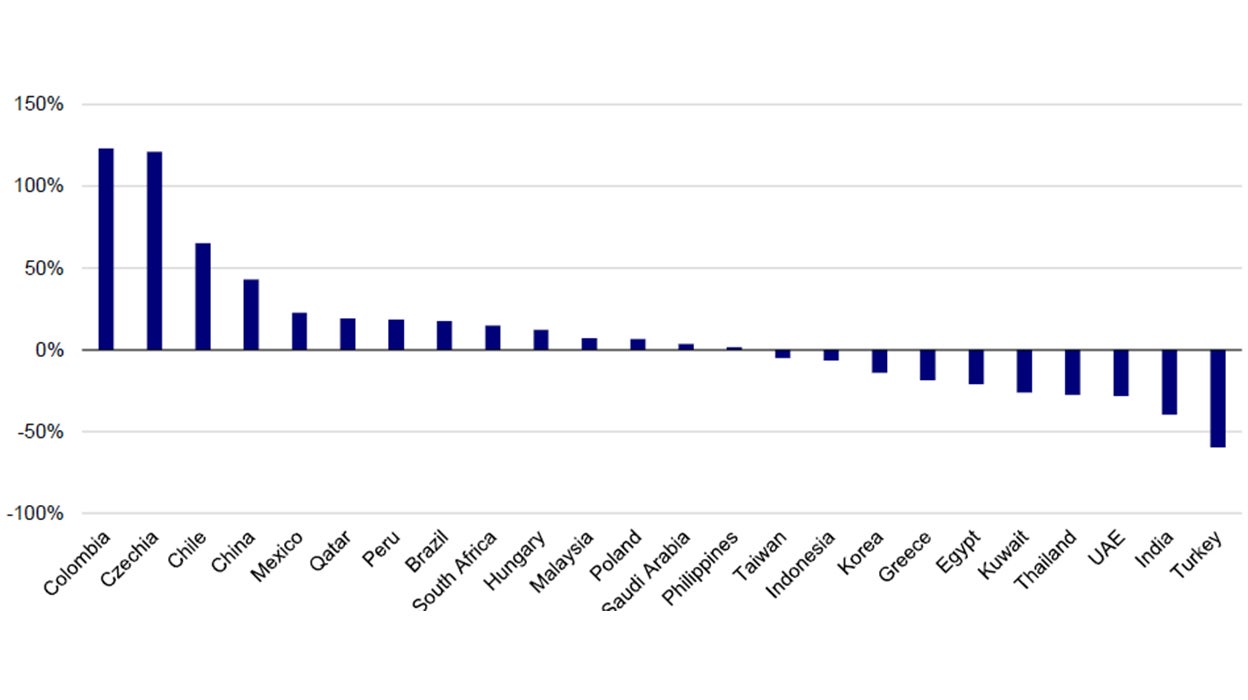

Notes: Data as of 31 January 2024. We use dividend yields from Datastream Total Market indices. The regional benchmark is the Datastream Total Market Emerging Markets (EM) index. The chart shows the ratio of the dividend yield on each market to that of the EM index, compared to the historical average for that ratio. We consider markets with positive values to be cheap, and those with negative values expensive. Source: Refinitiv Datastream and Invesco

Even if we are positive on EM equities overall, we think it is important to differentiate between such a diverse group of markets. Therefore, we examine the valuations of each constituent of the MSCI EM index using dividend yields relative to the EM benchmark versus their respective historical averages (Figure 3). In light of their strong returns since our last edition, we are not surprised that India and Turkey continue to appear overvalued. Despite their weaker returns, they are joined by Thailand and two of the four Middle Eastern fossil fuel exporters in the MSCI EM index: United Arab Emirates and Kuwait. Egypt, Greece and Korea complete the list of countries with relative valuations looking rich after strong returns since the end of Q3 2022 (in local currency terms).

Most of the rest of the Asia-Pacific region (Indonesia, Taiwan, the Philippines and Malaysia) look close to historical averages joined by Saudi Arabia and Poland. We would consider these countries to be close to “fair value” at this point.

South Africa may appear attractive on the surface, but its economy seems to be sliding into recession, while inflation remains high, and the uncertainty of forthcoming elections may have deterred investors driving dividend yields higher.

Latin American markets seem to be the most attractive with relative dividend yields higher than historical norms. We think that a lot of bad news is priced in making these countries the most attractive despite lingering uncertainty about how much of these high yields can be attributed to high payouts in the past

(these markets tend to be dominated by resource-related stocks). We think similar uncertainty applies to the relative valuations of Hungary, Qatar and Czechia, where extractive industries and utilities account for most of dividends paid, although high concentration of dividend payers is also an issue in these markets.

Finally, China appears to be the most attractive large economy within EM. Its relative dividend yield is well above its historical average suggesting attractive returns over the long term. Having said that, its equity market may need a catalyst before any sustainable turnaround. This could come either internally in the form of monetary or fiscal stimulus, or externally with a reacceleration in the global economy.