Uncommon truths: Don’t shoot the messenger: demographics suggest less growth

Falling fertility rates suggest less population growth, which could bring lower GDP expansion and less inflation. Africa appears relatively well placed; Europe, Asia and South America less so.

This is the next in a series of papers over the summer about long-term issues. The topic this week is demographics and the likely effect on economic outcomes. Later papers will consider the implications for savings, asset performance and climate change.

But first, a few comments about the developments of the last week. Central bank meetings came thick and fast but, as expected, there were no policy changes at the Bank of Japan, Bank of Canada or at the Fed. Two Fed committee members voted for a rate cut but that didn’t boost market faith in a September rate cut.

What did swing market opinion was Friday’s employment report, with non-farm payrolls increasing by only 73k in July (versus a Bloomberg consensus of 104k). Even worse, the June data (which had reassured markets when released) was revised down to a gain of 14k (from the original 147k), while May was revised down to 19K (from 144k). The US labour market appears weaker than originally thought, with an average monthly gain of 35k in the three months to July versus 127k in the three months to April and 209k in the last three months of 2024. If that weren’t enough, the Household Survey (used to calculate unemployment) suggests the average monthly change in employment in the last three months is -288k.

The upshot is that markets finished the week believing a Fed rate cut is more than likely in September, with two rate cuts likely by the end of the year (according to Bloomberg implied probabilities based on Fed Funds futures).

Second quarter GDP data published midweek also hinted at a weakening economy. Though GDP growth rebounded to an annualised 3.0% from -0.5% in Q1, the swing was due to weakening imports (after the surge in Q1). The underlying picture is one of weakness, with consumer spending growth of 1.4% and fixed investment spending growth of 0.4% (all annualised). Though the effect of tariffs remains hard to see in the inflation data, I think it is showing in activity data and I doubt the slew of tariffs announced in the last week will improve the mood.

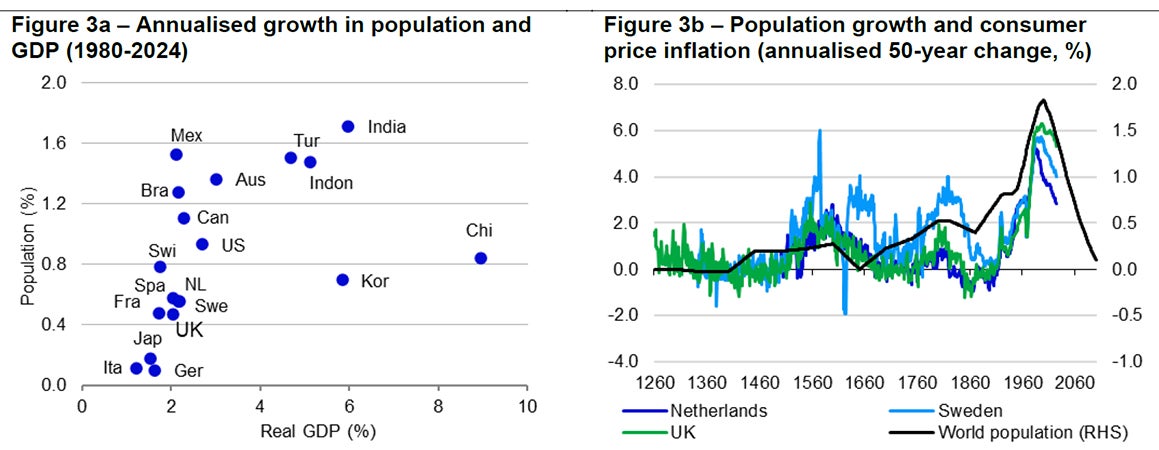

Leaving behind the immediate and turning to the distant future, if demographics is destiny, what does the ongoing deceleration in the world’s population tell us about our economic future? To be clear, the global population is still expanding, with UN estimates suggesting it had grown from 6.2bn in 2000 to 8.1bn in 2023. Further the UN projects that we shall number 9.7bn in 2050. However, the rate of growth is slowing: having peaked at 1.83% in 2000, the annualised rolling 50-year growth rate had eased to 1.46% by 2023 and UN projections suggest it will have fallen to around 0.1% by the end of the century (a level not seen since the 1600s – see Figure 3b).

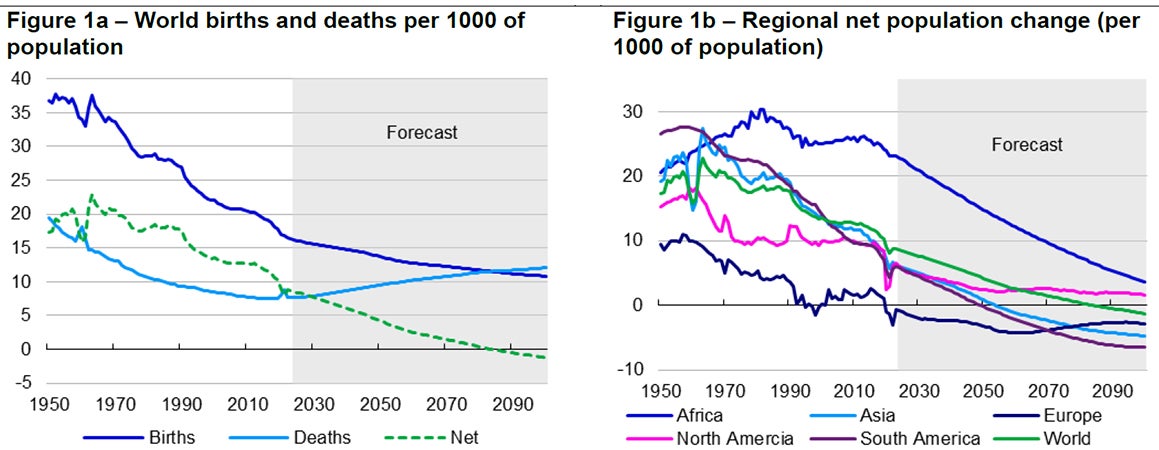

Figure 1a suggests that falling death rates (deaths per 1000 of population) have been helping over recent decades, but birth rates have been falling even faster. Hence the net change in population has been falling since 1963 and is expected to continue falling until it turns negative in the mid-2080s, when the global population is expected to peak at 10.3bn.

Note: Based on annual data from 1950 to 2100 (using United Nations (UN) estimates up to 2023 and UN Medium Variant forecasts thereafter). Shaded areas show forecast periods. Figure 1a: “Net” is births minus deaths. Figure 1b: Net population change allows for births, deaths and net migration. Source: United Nations World Population Prospects 2024 and Invesco Global Market Strategy Office.

Looking at the forecast portion in Figure 1a, it can be seen that the crude death rate is expected to rise (as a consequence of ageing populations), while the birth rate is expected to continue falling. Of course, the experience is expected to vary across the globe, with Figure 1b suggesting that Europe is already suffering population shrinkage, while Africa’s population is expected to continue expanding throughout the forecast horizon. Note that Figure 1b also allows for net migration, with Europe and North America being the main recipients of immigration flows (the 0.6 per thousand shrinkage in Europe’s population in 2023 came despite net immigration of 2.0 per thousand).

Though population deceleration is a universal phenomenon, Africa is expected to continue having the healthiest demographics. Next among the regions covered here comes North America, where positive net immigration is expected to keep population growth in positive territory to the end of the century. It will be interesting to see whether the policies of the current US administration change that balance.

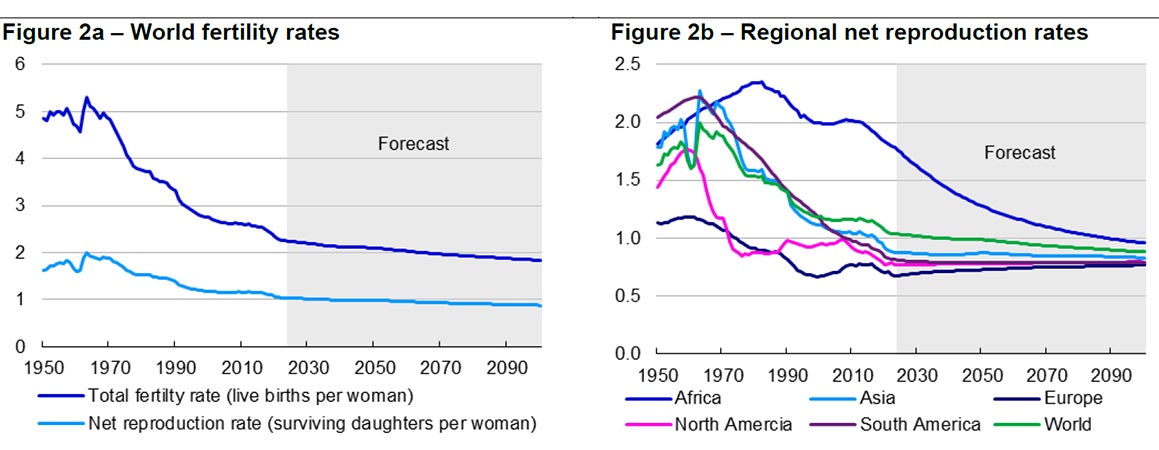

It is worth noting how UN population projections have changed over recent years. In the 2015 estimates, the UN suggested that total population would reach 11.2 bn by 2100 versus “only” 10.2 bn in the 2024 edition. This is partly because of the faster than expected decline in fertility rates. Figure 2a shows that whether we look at the number of live births per woman (total fertility rate) or the number of daughters per woman that survive to childbearing age (net reproduction rate), global fertility rates have declined since peaking in 1963. There appeared to be a noticeable acceleration in the decline in the 2018-2020 period. This may partly be explained by the pandemic but was set in motion well before that. Looking at UN projections, the 2022 version of World Population Prospects suggested the global net reproduction rate would be 1.06 in 2023, whereas the 2024 version suggests it was actually 1.04. Also, the 2022 version forecast it would be 1.01 in 2050 versus the 0.99 projected in the 2024 edition (1.0 is clearly a critical value below which the world’s population is not expected to replace itself).

Those are small downward adjustments but they appear to be a consistent feature of recent history. Figure 2b shows that it is global phenomenon, with all regions suffering a decline in net reproduction rates over recent decades. The steepest declines have been in Asia and South America, though in absolute terms the lowest net reproduction rates are seen in Europe and North America. Both of the latter two have net reproduction rates below 1.0, suggesting that without net immigration their populations would shrink (as is now the case in Europe). Based on Figure 2b, I believe Africa is the most likely source of migrants, especially considering the effects of climate change.

Not surprisingly, the countries with the highest net reproduction rates in 2023 were in or near Africa (Somalia 2.52, Mayotte 2.24 and Burundi 2.15). Those with the lowest rates were in Asia (Hong Kong 0.34, South Korea 0.35, Taiwan 0.42, Singapore 0.46 and China 0.47). This has obvious implications for population growth and especially working age (20-64 years) population growth. For example, UN projections suggest that South Korea’s working age population will shrink by 73% between 2023 and 2100 (by the end of the century, its working age population will be little more than one-quarter of its current level). China is projected to lose around 70% of its working age population, and Japan 47% (in Europe, Italy and Spain are expected to lose 52% and 46%, respectively).

Note: Based on annual data from 1950 to 2100 (using United Nations (UN) estimates up to 2023 and UN Medium Variant forecasts thereafter). Shaded areas show forecast periods. Net reproduction rate is the number of surviving daughters per woman (i.e. the number of daughters that reach childbearing age) and is based on historical data and forecasts of mortality data.

Source: United Nations World Population Prospects 2024 and Invesco Global Market Strategy Office.

That suggests there could be important geopolitical shifts over the rest of this century. For example, Asia today accounts for around 62% of the world’s working age population (China 20%, India 18%) but that is expected to fall to around 44% by 2100 (China 5%, India 14%). Expected to move in the other direction is Africa, with the UN forecasts suggesting its share will rise from around 15% today to 40% in 2100. Of course, population size doesn’t equate to economic power, a point proven by the fact that the US accounts for only 4% of the world’s working age population, a share that is unlikely to change over the rest of the century (based on UN estimates). On the other hand, Europe’s share is expected to fall from around 10% to around 5% (Europe includes Russia) and that of South America from around 6% to 3%.

Having established that World population growth is expected to progressively fade over the rest of this century and that Africa will be the region where growth will be strongest, while Europe, Asia and South America will see least growth, what could be the economic implications? Is demography destiny?

Figure 3a shows the historical relationship between population and real economic growth since 1980. There would appear to be a positive correlation (there is a similar relationship between population growth and nominal GDP growth). Though correlation doesn’t prove causality, I believe it is reasonable to assume that stronger population growth leads to higher rates of economic growth. China and South Korea appear to have generated even more economic growth than would be justified by their population growth (perhaps showing the role of development).

That would seem to argue for long-term global economic deceleration, with growth being strongest in Africa and weakest in Europe, South America and Asia. Those sceptical about the potential of Africa should consider that the continent’s GDP growth has often outstripped global growth over recent decades (see our country-by-country guide in Africa 2024).

As for inflation, conversations with investors suggest that views are mixed. Many argue that less working age population growth will lead to labour shortages and higher wage growth. Others suggest it will dampen demand for goods and services, and therefore less inflation. Figure 3b presents evidence in favour of the lower inflation argument. It suggests that over a number of centuries, the broad ebbs and flows of inflation in three European countries correlate with global population growth. I suspect that high population growth puts a strain on commodity markets, thereby boosting raw material prices and broad inflation. In that sense, OPEC may have been the tool that caused high inflation in the 1970s/1980s but it was the post-war demographic explosion that created the conditions to enable the oil price hike.

What all of this means for asset markets will be considered in the coming weeks. For example, how will savings behaviour change, in particular how much will be saved and where will savings come from? How will rising dependency ratios impact government yields (with rising supply of government debt but also higher demand from pensioners) and how will this interact with lower growth and less inflation? How will equities fare given a reduced supply of workers putting equities in their pension pots and lower economic growth? Finally, and happens every year, the changing demographic outlook will be factored into our global temperature change model.

Unless stated otherwise, all data as of 1 August 2025.

Note: Figure 3a: Based on annual real GDP and population data. See appendices for country abbreviations. Figure 3b: based on annual data from 1260 to 2100 and showing annualised rolling 50-year changes.

Source: United Nations World Population Prospects 2024, Global Financial Data, LSEG Datastream, Invesco Global Market Strategy Office.

Investment risks

The value of investments and any income will fluctuate (this may partly be the result of exchange rate fluctuations) and investors may not get back the full amount invested.