Uncommon truths: Are we boiling?

Recent experience suggests the world’s climate is changing. We may not be boiling but things could get worse and large mitigation and adaptation investments are likely to be needed.

“The era of global warming has ended; the era of global boiling has arrived.”, according to United Nations (UN) Secretary General Antonio Guterres Is he correct? In this paper I try to give an answer by updating my global temperature change model.

The Secretary General’s comments were in reaction to news that July 2023 was the hottest month on record. According to the European Union’s Copernicus Climate Change Service, the global average surface air temperature for July was 16.95C, the highest for any month since detailed records began in 1940.

That was 0.3C warmer than the previous record monthly high (July 2019), 0.7C warmer than the 1991-2020 average for July and 1.5C warmer than the estimated 1850-1900 average July temperature. The latter is symbolic, as the Paris Agreement aims to limit the rise in temperature since 1850-1900 to 1.5C.

Perhaps contributing to those record air temperatures are elevated sea surface temperatures (SSTs), which have been at record seasonal levels since April and on July 31 reached a record high of 20.96C (global average 60S-60N). The July 2023 global average sea temperature was 0.51C above the 1991-2000 July average (the North Atlantic anomaly was 1.05C). Not surprisingly, Antarctic Sea ice extent broke the July record, being 15% below the 1991-2020 July average (for the Arctic, the anomaly was a smaller -3%).

Those temperature data points simply confirmed what many people were thinking based on the extreme temperatures experienced in places as far-flung as China, Southern Europe and the Southwest of the USA. Meanwhile, Asia, Africa and South America each had their warmest July on record.

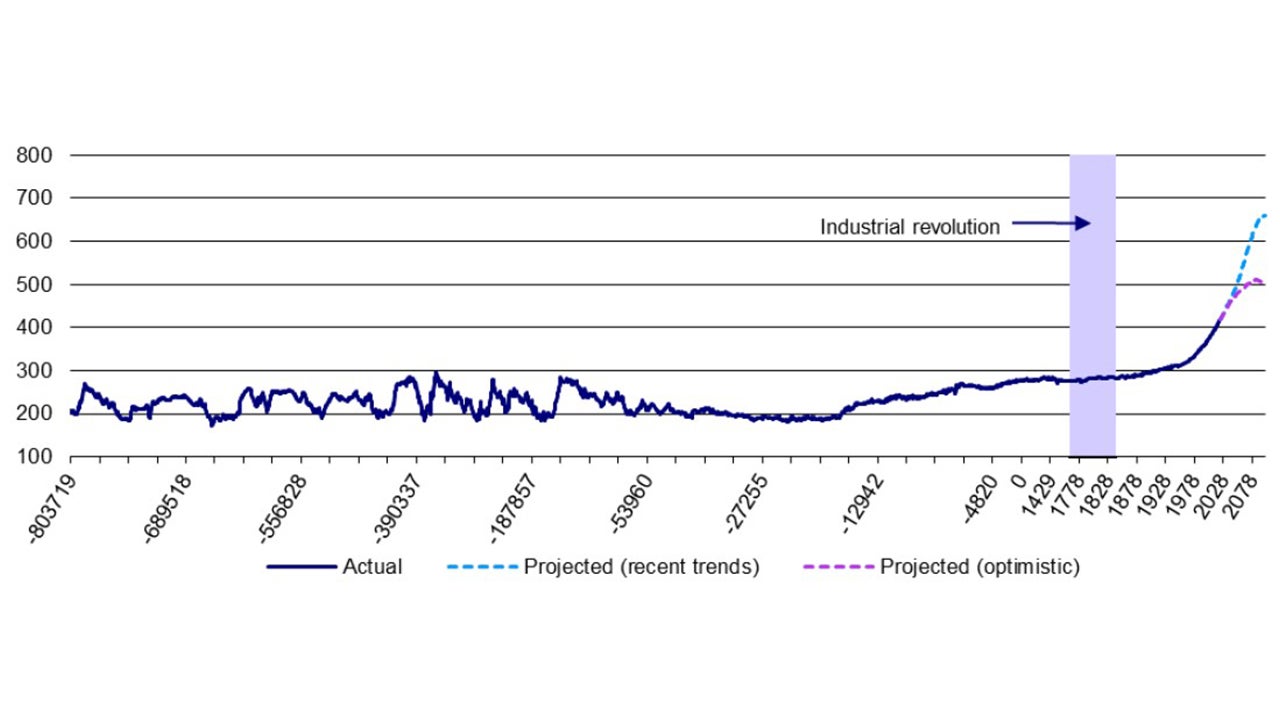

Are rising temperatures (and broader climate change) caused by human activity? NASA says: “the vast majority of actively publishing climate scientists – 97 percent – agree that humans are causing global warming and climate change.” Perhaps it is just coincidence but the atmospheric concentration of CO2 reached a new high of 418.53 parts per million (ppm) in 2022 (despite the temporary depressing effects of La Nina), according to data from the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Figure 1 shows this to be well above the norms of the last 800,000 years. As CO2 concentration appears to be correlated to CO2 emissions in the previous one hundred years, it seems likely that industrialisation and rising CO2 emissions may have contributed to rising temperatures (the molecules of greenhouse gases such as CO2 absorb energy, thus holding heat in the atmosphere that would otherwise have escaped). If so, there is hope that we can do something about it.

Note: “Actual” data is from the year -803,719 (i.e. 803,719 B.C.) to 2023. Data is not available for all years, so the date axis is not to scale. Data is shown for each year from 1750, using simple interpolation to fill any gaps. Data from 1958 to 2022 is based on observations at the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Mauna Lao Observatory on Hawaii. The 2023 datapoint (420.5 ppm) is based on the forecast change for 2023 produced by the UK’s Meteorological Office. Data prior to 1958 is derived from ice core records, as provided by NOAA Earth System Research Laboratories. Projections assume that CO2 concentration is determined by emissions in the previous 100 years (using an econometric relationship derived from data since 1750). Projections rely on forecasts of future CO2 emissions by low, middle and high-income countries (the global total being an aggregation of the three): “recent trends” assumes a continuation of recent trends in declines in the CO2 intensity of GDP and growth in GDP per capita, whereas “optimistic” assumes a more aggressive reduction in CO2 intensity (see the detailed explanation in the appendix). In both cases, population forecasts are taken from the UN’s World Population Prospects 2022. “Industrial revolution” is the period 1760-1840. Source: NOAA, Our World in Data, UK Meteorological Office, United Nations, World Bank, Refinitiv Datastream and Invesco Global Market Strategy Office

But, first, the bad news. CO2 emissions reached a new high in 2022 (39.3bn tonnes according to the Energy Institute Statistical Review of World Energy). I reckon they will continue climbing, using a model that calculates CO2 emissions as the product of population, GDP per capita and the CO2 intensity of GDP.

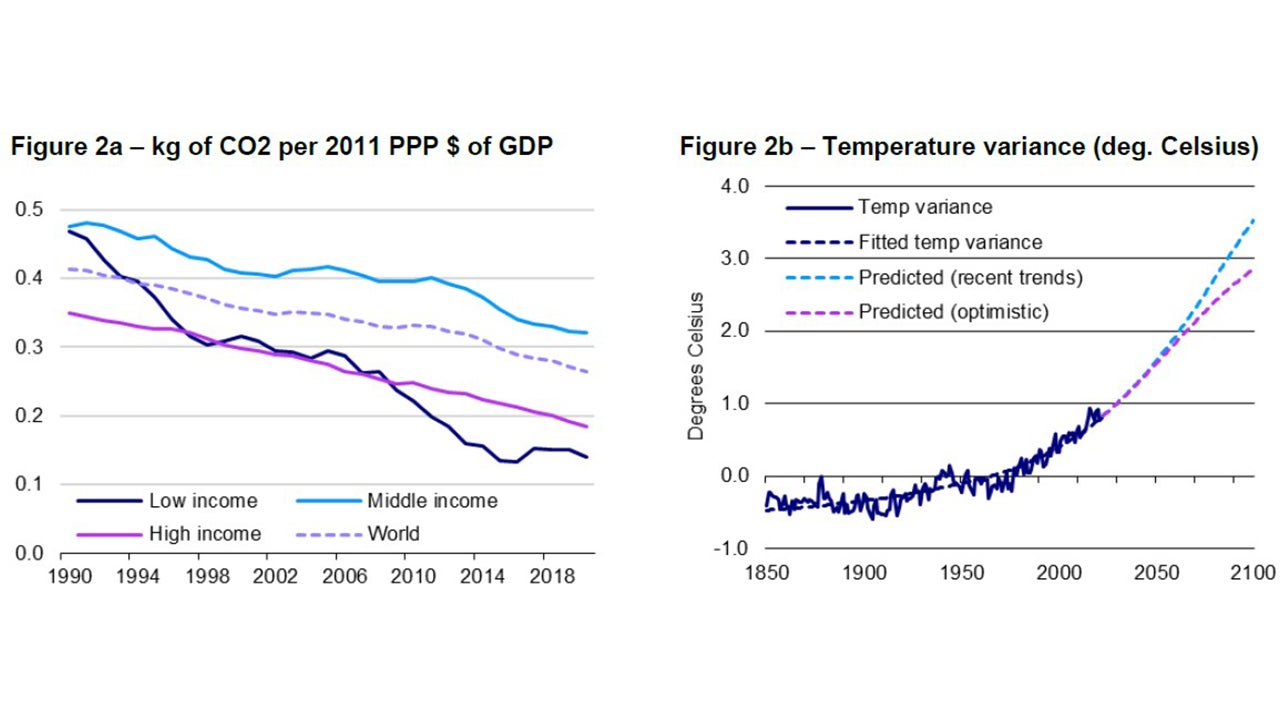

Of course, the outcome depends on the assumptions. UN projections suggest the world’s population will rise from 7.98bn in 2022 to a peak of 10.43bn in 2086. If real incomes (and spending) continue to rise, that 31% gain in population will require massive technological shifts to stabilise CO2 emissions. Figure 2a shows that we are on the right path, with a gradual decline in the CO2 intensity of economic activity. Technological change will hopefully drive it even lower.

Unfortunately, it isn’t happening fast enough. If CO2 intensity declines at the same rate as in the decade to 2020, I estimate that annual global CO2 emissions will have doubled by the time they peak in 2071 (see the appendix for detailed assumptions). Based on my models, this, along with what has already been emitted in recent decades, results in a continued rise in the atmospheric concentration of CO2 (see “Projected (recent trends)” in Figure 1). This leads me to conclude that the temperature change by the end of the century will be 3.9 degrees versus the 1850-1900 average, based on the model shown in Figure 2b (note that the chart shows the variance versus the 1961-1990 average).

A more optimistic scenario, that sees high income country gross emissions fall to zero by 2060 and a doubling of the rate of decline in CO2 intensity in low and middle income countries, gives the result that global CO2 emissions fall from here and would halve by 2090. That would be good news but CO2 concentration would continue to climb because of emissions over recent decades (see “Projected (optimistic)” in Figure 1). However, my model suggests that concentration would peak in 2086 (by coincidence just as the world’s population is expected to peak), though I still predict a temperature gain of 3.2 degrees versus 1850-1900 by the end of the century.

So, I wouldn’t say the world is boiling but it may be simmering. Even on my most optimistic scenario (accepting the simplicity of my models), the temperature change outcomes are likely to be dramatic, as are the potential implications in terms of volatile weather patterns, rising sea levels, agricultural production and migration flows. We may need big investment in carbon reducing and carbon removing technology, running the gamut from reforestation, through electrification of transport systems to renewable energy sources (as previously covered in The 21st Century Portfolio, November 2019, and recent editions of Economic Transition Monitor). In the meantime, large scale adaptation spending could be needed as we learn to live in a changing world.

Unless stated otherwise, all data as of 25 August 2023.

Notes: Figure 2a shows the CO2 intensity of GDP annually from 1990 to 2020 for low, middle and high-income countries (as currently defined by the World Bank). Figure 2b shows annual data from 1850 to 2100. It shows the historical global temperature variance (“Temp variance”), which is the global average land-sea temperature anomaly relative to the 1961-1990 average temperature in degrees Celsius, median estimate, as provided by UK Met Office Hadley Centre. “Fitted temp variance” is the result of a regression analysis that fits historical temperature variance to atmospheric CO2 concentration (using the natural logarithm of the 100-year moving average of concentration, on the assumption that temperature at any moment is determined by CO2 concentration during the previous 100 years). “Predicted (recent trends)” applies that fitted relationship to our forecast of CO2 concentrations, assuming that recent trends in CO2 intensity and GDP per capita continue, though with some convergence between World Bank income groups after 2050 (see appendix for details). “Predicted (optimistic)” assumes a doubling of the rate of decline in CO2 intensity (with the added assumption that high income CO2 emissions trend to zero in 2060). Source: NOAA, Our World in Data, UK Meteorological Office, United Nations, World Bank, Refinitiv Datastream and Invesco Global Market Strategy Office