Uncommon truths: Beware talk of soft landings

Economies appear to be more resilient than expected. A strong US payroll gain in January encouraged talk of a soft landing and provoked a reversal of the recent uptrend in assets. I believe this will prove to be a temporary phase of market consolidation, as an overstretched US consumer pulls back and inflation continues to fall rapidly during the first half of 2023.

The exceptionally strong US payrolls data for the month of January has encouraged the notion of a soft landing. It may be thought that a 517k monthly gain in non-farm payrolls (and big upward revisions to prior months) would be cause for celebration, given the lingering fears of recession.

Of course it was not, given that it has provoked fears of inflation remaining higher for longer, which could push the Fed to raise rates even higher and for longer. Hence, bond yields have risen and the dollar has rallied, while stocks and gold have fallen. The big question is whether this reversal of recent market trends signals the start of a new bear phase (taking bond yields higher and stocks lower) or whether it is just a healthy pause in a new bull market?

I suspect it is a healthy pause in a new uptrend in asset prices (we were bound to get consolidation at some stage). The first reason for thinking so is that I doubt the 517k payroll gain reflects the current state of the US economy. Pretty much every other indicator (ISM surveys, GDP, ADP employment, Challenger job cuts) points to a decelerating economy. Hence, I believe the outsized January payrolls gain will prove to be an aberration, my best guess being that it reflects problems with seasonal adjustments. If so, there is likely to be payback at some stage during the year (with a surprisingly weak number) and, at the very least, a reversion to lower (and falling) numbers over the next few months. Also, I wouldn’t be surprised to see a downward revision to the January number when February data is published.

Even better, and despite the apparent strength of the labour market, US wage growth continues to ease. The exceptionally high peak in average hourly earnings inflation (5.9% in March 2022) may have been due to post-pandemic distortions in the labour market (in my opinion), whereby shortages in some sectors (hospitality, say) led to an abnormal bidding up of wages in some sectors. That wage inflation is moderating (to 4.4% in January 2023), even before unemployment has risen, could suggest those distortions are now fading.

Further, year-on-year commodity price gains have turned negative (based on the S&P GSCI Spot Index), which should ensure further downward pressure on headline inflation over the coming months. Hence, I am not sure the Fed should put too much weight on what I think was a rogue payroll number.

Having said that, economies (and profits) have been more resilient than many had imagined, myself included. Take for example, recent GDP data from the UK, which showed that the economy was flat in 2022 Q4 (0.0% quarter-on-quarter growth, after -0.2% in Q3). That doesn’t sound great but it means that the UK appears to have avoided two consecutive quarters of negative growth, which many consider to be the technical definition of recession (though on that score, the US had a recession in the first half of 2022!). The eurozone did even better, with 0.1% growth in Q4 (after 0.3% in Q3) and the US was positively humming (0.7% after 0.8%, when expressed in the non-annualised format used elsewhere).

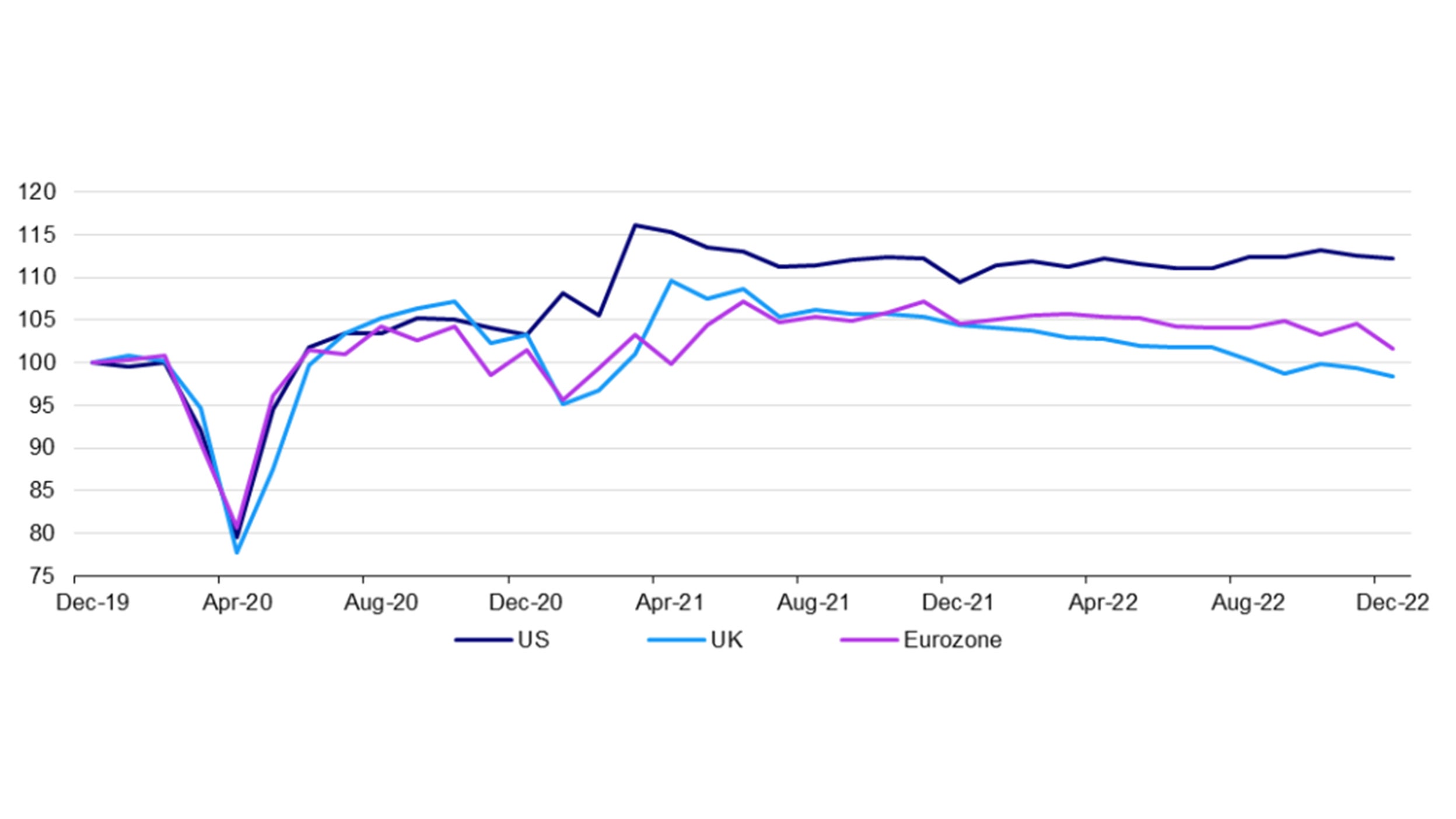

Notes: Monthly data from December 2019 to December 2022. Retail sales are shown in price adjusted (real) terms and rebased so that the December 2019 level = 100. Source: Refinitiv Datastream and Invesco

Figure 1 shows one reason why the UK has been lagging. Its retail sales volumes (i.e. when adjusted for inflation) have been on a downward path since the post-lockdown peak of April 2021 and are now below where they were in December 2019 (as of December 2022). Eurozone retail sales volumes have fallen recently but are still 1.6% above the December 2019 level, having peaked in June and November 2021. The real outlier is the US, with retail sales volumes 12.1% higher in December 2022 than three years earlier, though broadly flatlining since mid-2021.

Closer inspection of Figure 1 reveals that retail spending patterns across the three economies were remarkably similar in the early stages of the pandemic. Spending volumes in the US only started to diverge in January 2021 and I can think of two reasons why. First, the US was easing its Covid restrictions, with the Blavatnik Stringency Index falling from its peak of 75.5 on 1 December 2020 to 68.1 on 3 February 2021 (this index ranges from 0 to 100). That may not seem like a big easing but European countries were imposing another round of lockdowns at that stage, with the German and UK stringency indices rising from 67.6 to 83.3 and from 67.6 to 88.0, respectively. As a footnote, by the end of 2022, those indices had fallen to 14.8 (Germany), 5.6 (UK) and 37.0 (US).

The second (and perhaps more powerful) reason for the outperformance of the US consumer was fiscal. Most governments supported household incomes during 2020 but the US treasury made the second and third payments to individuals in January and March 2021, months in which aggregate personal disposable income rose by $1.8trn (a rise of around 10%) and $4.1trn (23%), respectively.

Taken together, the lack of further lockdowns in the US and the substantial boost to disposable income, explain why US retail sales volumes were so much stronger than in Europe in the first half of 2021, in my opinion. I think they have also held up relatively well since then, in the face of the squeeze on real incomes, because the US personal savings ratio has fallen close to historical lows (2.9% in 2022 Q4 versus a low of 2.5% in 2005 Q3). In fact, US households have used up all of the Covid fiscal support (and more), with net dissaving since December 2019.

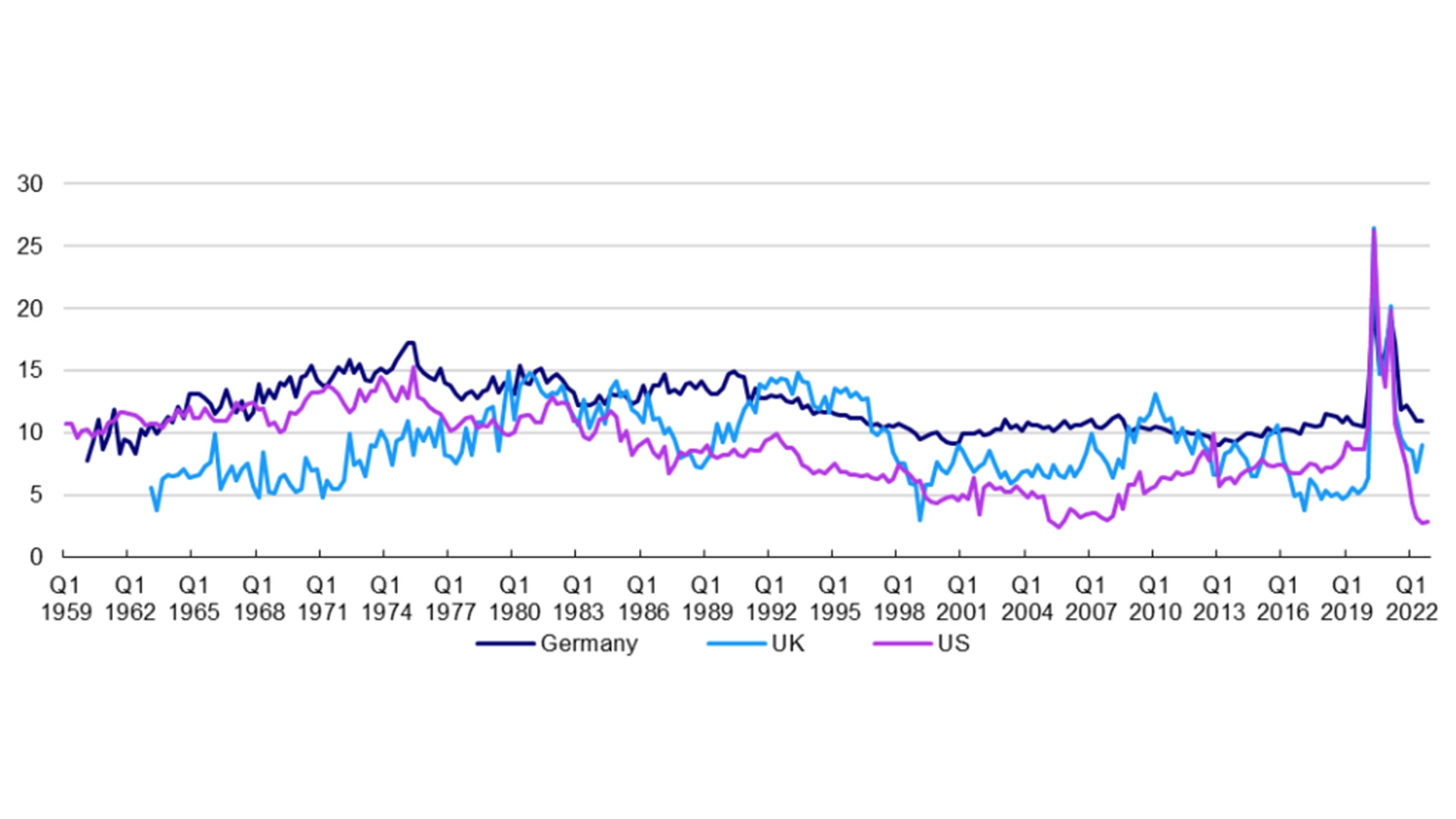

Figure 2 shows that the decline in the household savings rate has been far more aggressive in the US than in Germany or the UK. In fact, the US savings rate is only one-third of what it was in 2019 Q4, whereas those for Germany and the UK are both higher than their pre-pandemic levels. It could be that US households were encouraged to spend larger shares of their incomes by the boost to wealth that came with the asset price gains of 2021. But in that case, I would now expect a rise in the savings rate as wealth fell during 2022. In any case, with the savings rate so low, I doubt that US consumer spending can continue to grow at the recent pace. On top of the fact that US fixed investment spending has fallen in the last three quarters, any weakening in consumer spending could imperil the notion of a soft landing.

In conclusion, I suspect the recent strong payrolls data in the US was a red herring and I expect further deceleration in that economy. Consequently, I remain confident that inflation will continue to fall rapidly throughout the first half of 2023 and that the Fed will call a halt to rate hikes in mid-2023 (despite the January uptick in inflation in countries such as Norway and Spain, which I think had more to do with what was happening a year ago than with what is happening now). I believe this will keep asset prices on an uptrend, after a short period of consolidation.

All data as of 10 February 2023, unless stated otherwise.

Note: Quarterly data from 1959 Q1 to 2022 Q4. Source: Refinitiv Datastream and Invesco