Uncommon truths: Can yields go much higher?

The recent rise in long yields and bear steepening of yield curves has been painful. Whenever 10-year US yields have been much higher then now, either inflation or growth (or both) was higher. I doubt yields can go significantly higher for very long and favour longer maturities (despite the recent pain).

Three days of meetings with investors in Spain this past week revealed confusion about the direction of long yields and where to be positioned on the maturity spectrum. I think it is fair to say that most investors are feeling battered and bruised by the recent bear steepening of yield curves.

The 10-year US treasury yield seemed to be heading for 5% in the past week (it peaked at 4.88% on 4 October and finished the week at 4.81%). It is barely believable that it was 3.31% just six months ago (6 April 2023), let alone 0.51% little more than three years ago (4 August 2020). It is now commonplace to see forecasts that it will reach 6%-7%.

Is that possible? Well, of course, anything is possible, especially given the build-up of momentum over recent weeks (and the weekend attack on Israel by Hamas that could, I think, push oil prices and inflation higher if tensions persist and other countries get involved). However, Figure 1 shows how rare such an outcome would be. Outside of the 1970-2000 period, the 10-year US yield has rarely been above 6% (in fact not since the early 1860s). Even more striking is that it has hardly ever been above 5% since 1870 (except for that 1970-2000 period).

Note: Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Based on monthly data from December 1790 to October 2023 (as of 6 October 2023). Source: Global Financial Data, Refinitiv Datastream and Invesco Global Market Strategy Office

Turning to those periods when treasury yields were noticeably and durably higher than today, the cause seems to have been high inflation, high trend growth or a combination of the two. The 1970-2000 period was marked by high inflation, with the annualised 10-year rate of US consumer price inflation climbing from 2.6% at the start of the 1970s to a peak of 8.8% in mid-1982 (it is currently 2.7% but still rising due to lag effects).

The more usual 12-month CPI change was already 6.2% at the start of the 1970s and peaked at 14.8% in March 1980. On the other hand, the 10-year yield peaked at 15.8% in September 1981, a full 18 months after the peak in inflation (for reference, US CPI recently peaked at 8.9% in June 2022). The rate of inflation then trended down and had fallen to 3.4% in December 2000, when the 10-year yield was 5.12% (not too far from the current readings of 3.7% for CPI and 4.81% for the 10-year yield). The history of this period suggests that bond yields lag inflation on both the upside and the downside.

That 1970-2000 period also had much better economic growth than now (I believe that real yields are linked to trend growth, when central banks are not distorting markets). The annualised 10-year rate of US GDP growth was between 4.2% and 4.7% in the latter half of the 1960s and early 1970s. It remained between 2.5% and 3.5% during most of the rest of the period up to 2000 (and never went below the oil shock inspired 2.1% recorded in 1982). Looking back to the 1790s (the 10-year yield briefly topped 8.0% in 1798), the economy was growing strongly, with annualised GDP growth above 6% in the 10 years to 1800. That wasn’t a fluke – the annualised 50-year growth rate was between 4.0% and 5.0% during the period up to 1900, when 10-year yields were usually between 5% and 7%.

However, things are now very different, with annualised 10-year GDP growth below 2.0% for much of the period since the global financial crisis (GFC), which should depress real yields versus those earlier periods.

Nevertheless, just as the very high yields of 1970-2000 were an aberration (seen in the context of longer history), so were the low rates of recent years. A 10-year treasury of 0.51% (with the real TIPS yield below -1.0%) could not be seen as anything other than transitory, caused by low inflation (after the collapse of commodity prices in 2020), anaemic trend growth rates (which depressed real yields) and central bank purchases of government debt (which further depressed those real yields).

Inflation has since moved higher but I expect it to continue normalising back towards central bank targets (as indicated by a 10-year inflation breakeven rate of 2.31%). At the same time, central banks are now less of a distorting influence -- Fed holdings of treasury securities have fallen by 14% since mid-2022. I believe the switch from quantitative easing to quantitative tightening has been a major factor in the rise in real treasury yields, which at 2.48% (10-year) are now above what I would expect over the long term (given my view that trend US GDP growth is unlikely to exceed 2.00% by any great margin).

Based on the above, I doubt that US long yields will go much higher for very long. Factors that could change my mind would be a significant boost to long-term inflation (a rerun of the aftermath of the Yom Kippur war, for example), a sustained rise in economic growth (due to the beneficial effects of AI, for example), a rise in investment relative to savings (due to climate change mitigation and adaptation spending, for example) or a rise in the risk premium applied to US government debt (due to rising indebtedness, say). All of these factors are possible but balancing them will be the depressing effect of long term global population deceleration.

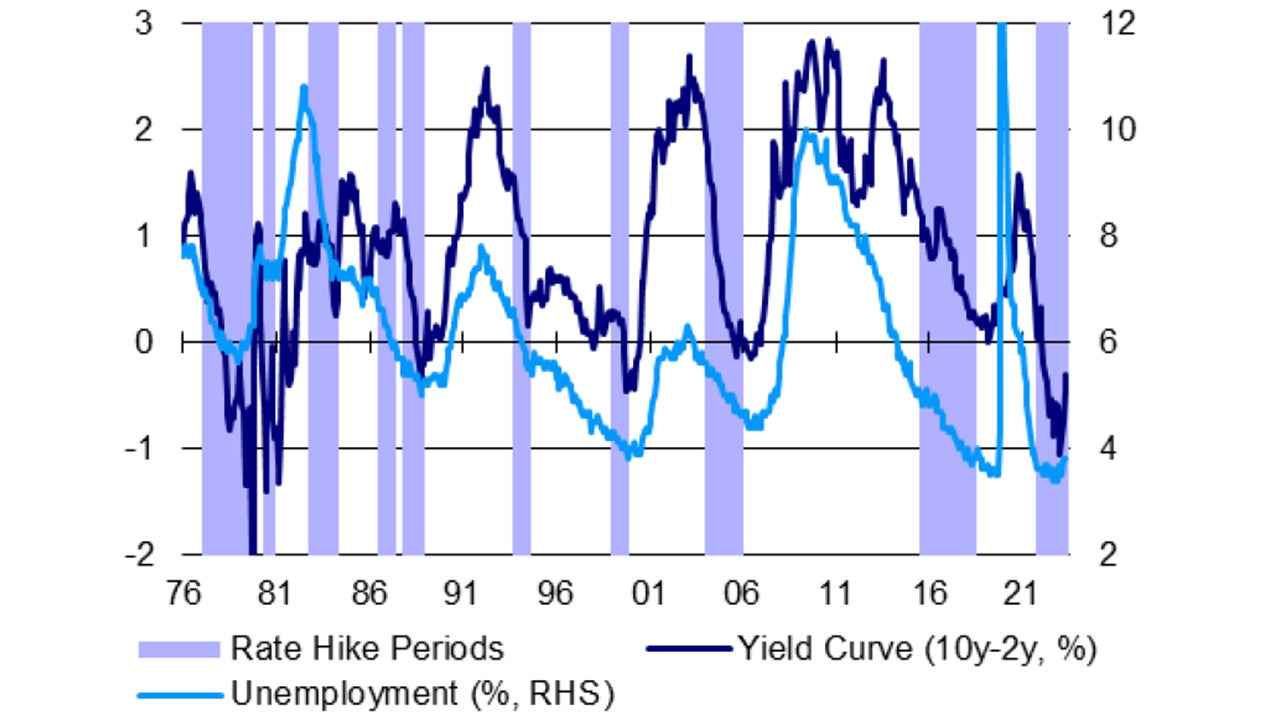

My conclusion is that US government bond yields have moved back into “interesting” territory (we are Overweight US treasuries in our Model Asset Allocation – see Figure 6). But what about positioning on the yield curve? Figure 2a shows an uncanny correlation between turning points in the US unemployment rate and the 10y-2y yield curve. Despite the surprising strength in September payrolls (reported on Friday), there has been a mild upturn in unemployment in recent months. Hence, the steepening of the yield curve should come as no surprise.

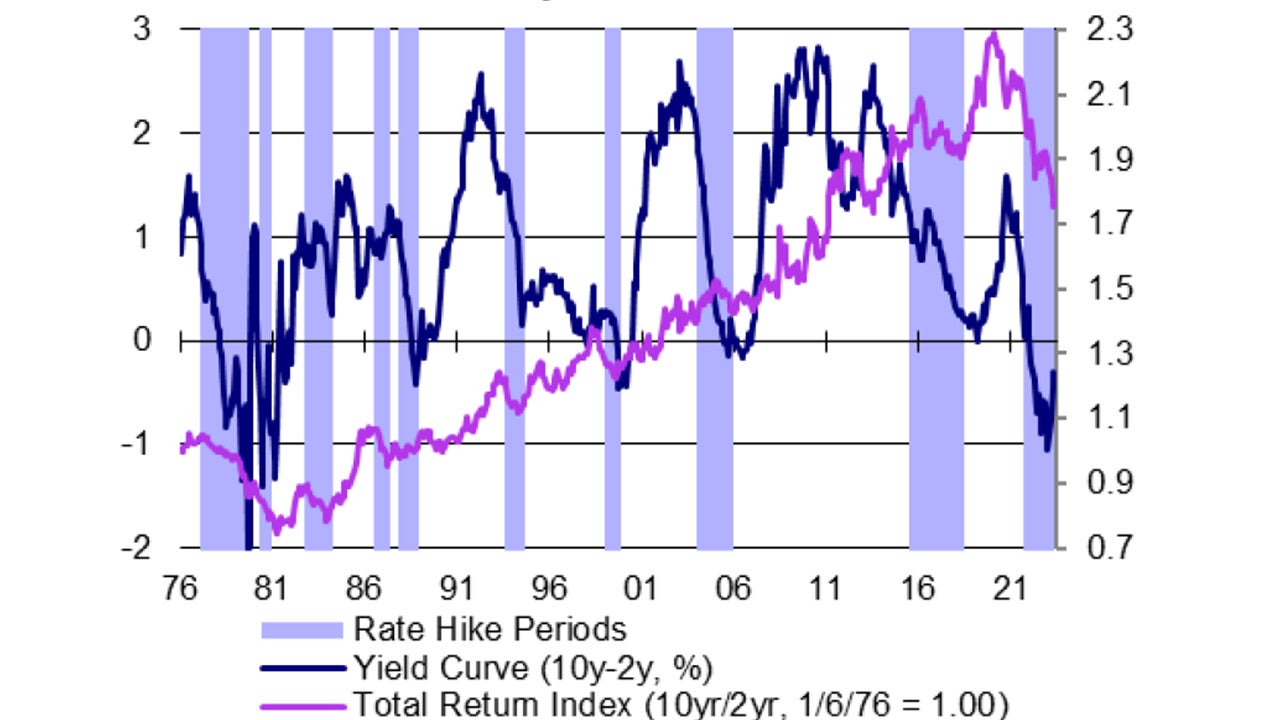

More shocking is the nature of the steepening. Figure 2b shows that 10-year treasuries have outperformed 2-year treasuries on a trend basis. However, that trend is periodically interrupted. In particular, shorter maturities have tended to outperform when the Fed is raising interest rates, despite the flattening of the yield curve (because duration works against you when all rates are rising). This has certainly been the case over recent years, just as it was in the late-1970s/early 1980s when the US yield curve was last so inverted.

Looking ahead, Figure 2b shows that longer maturities have tended to outperform when the yield curve steepens. This has not been the case in recent weeks, perhaps because the recent steepening is perhaps unique: typically in the past, the steepening occurred after the last Fed rate hike, whereas the fear is that this Fed tightening cycle is not yet over (perhaps because it started so late – see Figure 2a). If I am right about 10-year yields now being attractive, I doubt that the recent bear steepening will continue for long (I think it makes recession more likely) and I prefer longer maturities.

Unless stated otherwise, all data as of 6 October 2023.

Notes: Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Based on monthly data from June 1976 to October 2023 (as of 6 October 2023). “Rate hike periods” show periods when the US Federal Reserve was raising its policy rate. “Yield Curve (10y-2y, %) shows the difference between the US treasury 10-year yield and the US treasury 2-year yield. “Tot Ret (10yr/2yr, 1/6/76 = 1.00)” shows the ratio between the total return index for 10-year US treasuries and that of 2-year US treasuries, rebased to 1.0 on 1 June 1976. Total returns are calculated using movements in the respective yields on a daily basis to derive price movements, which are added to income flows assuming daily sales and repurchases to maintain constant maturities). Source: Refinitiv Datastream and Invesco Global Market Strategy Office