Uncommon truths: Global Debt Review 2024

After rapid declines in 2021 and 2022 (from record highs in 2020), global debt to GDP ratios increased slightly in 2023. The effect of higher interest rates is yet to be fully seen in debt service ratios but we can see the first signs. Businesses appear to have reduced debt drastically in some countries.

The man from Mars may question whether planet Earth has a debt problem (if so, to whom is it owed?). However, the global financial crisis (GFC) showed that, even if net debt is zero, it is difficult to unwind that debt when there are so many interlinkages. We therefore assume that more debt brings more risk. Hence, our annual review of global debt. Now that the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) has published its 2023 data, we are able to deliver the next instalment.

Nearly three-quarters of the record gain in global debt to GDP ratios in 2020 had been reversed by 2022, when PPP (purchasing power parity) exchange rates are used (all had been reversed when using market exchange rates). The sharp jump in debt to GDP in 2020 was the result of a combination of rising debt (especially in the public sector) and falling GDP (both were due to the effects of the Covid pandemic). Though, the decline in the debt ratio in 2021 was entirely due to the jump in GDP, as debt continued to rise, that of 2022 was due to a mix of falling public sector debt and rising nominal GDP. However, there was something of a setback in 2023, with global debt ratios rising slightly, due to a rise in debt.

The global debt to GDP ratio rose to 232.6% in 2023 from 230.7% in 2022, based on the BIS “All-Country” non-financial sector debt to GDP ratio, using PPP exchange rates to convert to US dollars. That debt to GDP ratio was 224.3% in 2019.

We believe that using PPP exchange rates to calculate such aggregates avoids the volatility that comes with market exchange rates. For example, using market exchange rates, the BIS All-Country aggregate debt-to-GDP ratio rose from 243.2% in 2019 to 285.4% in 2020 and has since fallen back to 245.1%.

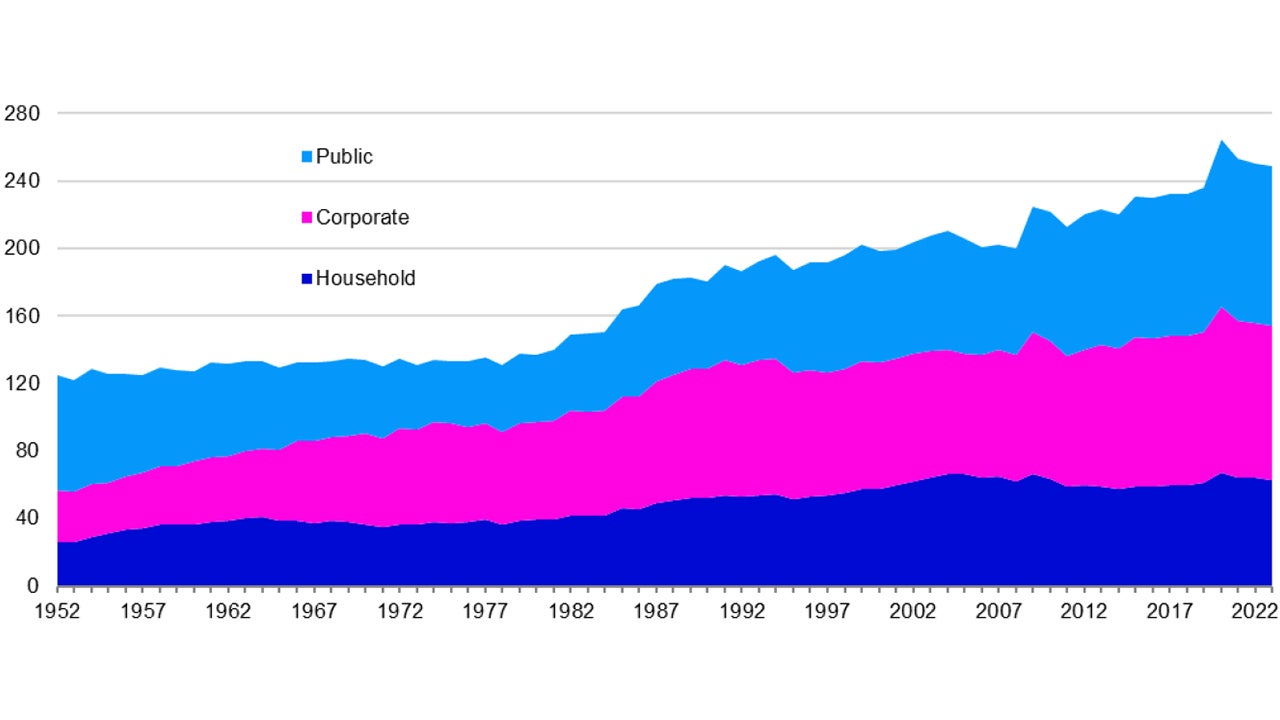

The BIS All-Country aggregates only go back to 2002, so we have constructed our own aggregate across the world’s 25 largest economies (measured by GDP in 2019-23). They accounted for around 84% of World GDP in 2023, according to IMF data. Figure 1 shows the results and suggests that, after reaching a new high of 264.6% in 2020, the global debt to GDP ratio fell back to 248.4% in 2023 (it was 236.4% in 2019). Our measure is based upon actual exchange rates, so we use a smoothing process to dampen the effect of exchange rate swings and this may explain why this measure declined in 2023 (see the note to Figure 1).

On that basis, global debt to GDP declined in household and corporate sectors and was stable in the public sector, though debt increased in all categories (as was also the case for the BIS all country ratios).

Note: Based on annual data for the 25 largest economies in the world (as of 2019-2023). Data was not available for all 25 countries over the full period considered. Starting with only the US in 1952, the data set was based on a successively larger number of countries until in 2008 all 25 were included in all categories. The data for all countries is converted into US dollars using market exchange rates. Unfortunately, debt is a stock measured at the end of each calendar year, whereas GDP is a flow measured during the year so that when the dollar trends in one direction it can distort the comparison between debt and GDP. To minimise this problem, we use a smoothed measure of debt which takes the average over two years (for example, debt for 2023 is the average of debt at end-2022 and at end-2023).

Source: BIS, IMF, OECD, Oxford Economics, LSEG Datastream and Invesco Global Market Strategy Office

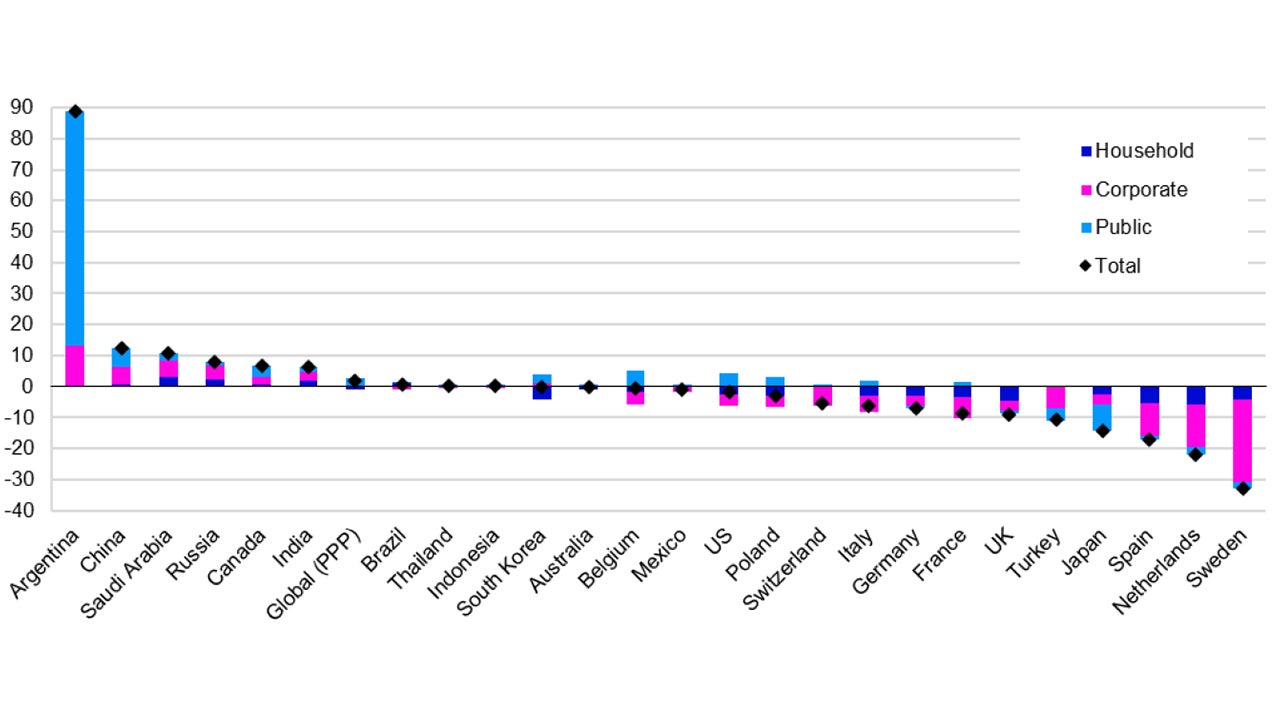

The biggest contributor to the gain in global debt in 2023 (in US dollars) was the US, with a rise of $3.7trn during the year, followed by China with a gain of $3.0trn. However, Figure 2 shows that the US debt-to-GDP ratios fell by 1.6 percentage points (ppts), while that of China rose by 12.5 ppts. The reason for the discrepancy is that growth in nominal GDP in the US was greater than the growth in debt, while the reverse was true in China (nominal GDP growth was also stronger in the US than in China).

The global debt ratio increased by around 1.9 ppts, with the majority of the rise accounted for by public sector debt. Total debt ratios increased in 9 of the 25 countries that we follow, with the biggest gains in Argentina, China and Saudi Arabia. Public sector debt played a role in all three, as did corporate debt, while rising household debt was also a factor in Saudi Arabia. At the other end of the spectrum, Sweden, the Netherlands and Spain saw big declines in their overall debt ratios, with falling corporate debt the most important factor.

Looking to longer term trends, total debt ratios have risen substantially in the last 10 years. The global debt to GDP ratio increased by 23.8 ppts in the 10 years to 2023 when using PPP exchange rates (or 18.8 ppts using market exchange rates). Most of that rise was already in place by 2019. The 10-year rise was largely due to public and corporate debt.

16 of the 25 countries experienced a rise in their total debt to GDP ratio over the last 10 years, Argentina being the most extreme with a gain of 129.8 ppts to 199.1%, followed by China with a gain of 81.3 ppts to 283.4% (more than half of the gain was due to the public sector, followed by households).

The Netherlands (-102.4 ppts) and Spain (-73.6 ppts) have seen the most impressive declines in debt ratios over the last 10 years, with falling corporate and household debt ratios playing the most important role in both countries.

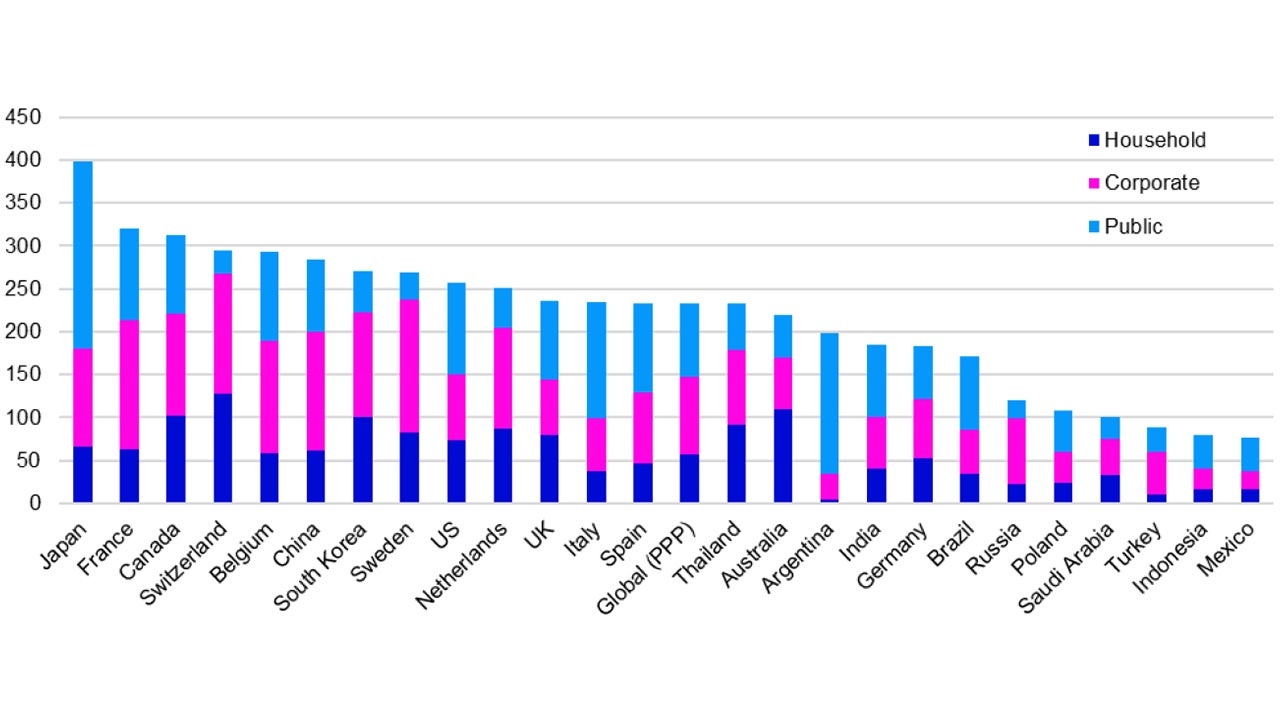

So where does this leave accumulated debt across countries? Figure 3 shows debt to GDP ratios for the 25 countries that we follow. As has been the case for some time, the countries with the biggest debt burdens are to be found in the developed world, with Japan once again leading the way, though its debt to GDP ratio fell once again, to 398.8% in 2023 from 412.9% in 2022 and a peak of 420.9% in 2020, according to BIS data. The next two countries (France and Canada) are the same as last year. The first change in ranking occurs at #4, with Switzerland moving up from #5 and replacing Sweden, which falls to #8.

At the other end of the spectrum, the two countries with the lowest debt ratios (Indonesia and Mexico) are unchanged from last year.

Other countries on the move in 2023 in Figure 3 include: Belgium (from 6th to 5th), China (8th to 6th), South Korea (9th to 7th), US (10th to 9th), Netherlands (7th to 10th), UK (12th to 11th), Italy (13th to 12th), Spain (11th to 13th), Argentina (21st to 16th), Germany (16th to 18th), Brazil (18th to 19th), Russia (19th to 20th), Poland (20th to 21st), Saudi Arabia (23rd to 22nd), Turkey (22nd to 23rd).

Note: Based on year-end local currency non-financial sector debt-to-GDP ratios. “Global (PPP)” uses BIS “All reporting countries” data, using PPP exchange rates (it is based on a larger sample of countries than is shown in the chart). The change is calculated as the end-2023 debt to GDP ratios minus those of end-2022. The countries shown are the 25 largest in the world by GDP, as of 2019-23.

Source: BIS, LSEG Datastream, and Invesco Global Market Strategy Office

So, after a sharp rise in debt ratios in 2020, there were declines in 2021/22, but the direction was mixed across countries in 2023, with global totals rising. If economies continued to expand, we would normally expect a decline in debt ratios as public sector expenditure declines and public and private revenues increase. However, many economies are slowing, debt ratios have already risen in some places and we fear that recession is possible in some countries.

Of course, debt only becomes a problem when debt service ratios increase. The rise in debt to GDP ratios since the global financial crisis was easily absorbed because bond yields fell to historical lows in the developed world. However, the sharp rise in yields during 2022/3 may have changed that. Governments have the luxury of being able to use the tax system to increase income if debt service ratios increase. The private sector has no such ability (raising prices may damage sales), so it is perhaps more important to focus on the affordability of private sector debt.

China is a good example of how rising debt over the last 10 years didn’t turn into a financing problem. BIS private non-financial sector data shows that China’s debt service ratio (interest payments plus amortisations divided by income) increased by only 1.5 percentage points (from 17.2% in 2013 to 18.7% in 2023), despite a 35.6 percentage point increase in the private sector debt to GDP ratio (to 200.4%).

However, interest rates and bond yields have risen sharply over recent years, which could boost debt service ratios. Of course, the rise in interest rates will take time to boost funding costs as some of the debt will be on a fixed-rate multi-year basis. Nevertheless, over the last three years there were noticeable gains in private sector debt service ratios in Brazil (+8.0 ppts to 25.7%), Turkey (+6.0 ppts to 20.3%) and South Korea (+3.6 ppts to 23.7%). The rise in Turkey’s debt service ratio came despite a substantial fall in the private sector debt to GDP ratio.

Among the 25 largest economies that we follow, the only one to enjoy a sizeable decline in the private sector debt service ratio was the Netherlands (-4.4 ppts to 21.5%). This reflects a 47.9 ppts decline in the private sector debt to GDP ratio to 205.1%, with the corporate sector accounting for around two-thirds of that (and it also experienced a bigger decline in the debt service ratio than the household sector).

For the most part it is not the household sector that faces difficult debt service ratios (with perhaps the exceptions of Australia, Canada, the Netherlands, South Korea and Sweden). More problematic is corporate debt and we suppose the biggest threat would be in countries where service ratios are the highest. As of 2023 that list of countries would be France (non-financial corporations debt service ratio of 58.9%), Canada (53.5%), the Netherlands (48.2%), South Korea (43.7%) and Sweden (42.7%), with the US not far behind on 41.9%. For the most part, those are the countries in which corporate sector debt is the most elevated (unfortunately, the BIS does not show the split between household and corporate sector debt service ratios in China, where corporate sector debt is high).

Unless stated otherwise, all data as of 19 July 2024.

Note: “Global” uses BIS “All reporting countries” data and is calculated using PPP exchange rates (it is based on a larger sample of countries than is shown in the chart). The countries shown were the 25 largest in the world by GDP, as of 2019-2023.

Source: BIS, LSEG Datastream and Invesco Global Market Strategy Office