Uncommon truths: Joining the dots: UK budget, banks, gold and AI

Though unpopular in the media, the recent UK budget seemed to calm financial markets. It also helped UK bank share price performance and may shed light on the popular themes of gold and AI.

The 26 November UK government budget was eagerly anticipated…in the UK. The post-budget decline in gilt yields and appreciation of sterling suggest the budget was well received by financial markets, though UK media reaction was less kind. In my opinion the budget was too piecemeal to be of great consequence and speaks to the constraints faced by Chancellor Reeves and the lack of vision of Keir Starmer’s government. A full description of the budget can be found in UK Budget: The waiting game is over by Invesco’s Graham Hook and Ben Jones.

For macro-economic and financial market purposes the main take-aways are an extra £26bn in tax revenues by 2029-30 and an additional £11bn of spending by 2029-30 (mainly on welfare). The upshot will be a record 38% tax/GDP ratio in 2030-31 (according to the UK Office for Budget Responsibility, OBR) and an increase in the headroom versus the primary fiscal rule to £22bn (it was the latter that reassured financial markets, in my opinion).

Graham and Ben see little in the budget to change the dial on the UK economy and I agree. That probably explains the indifferent stock market reaction (the FTSE 100 is up 1.2% since the day before the budget, the same as for the S&P 500 and less than the 1.7% gain in the Euro Stoxx 50, as of 28 November 2025, according to Bloomberg data). Where the budget did seem to have a positive impact was in the gilt market, where 30-year yields have fallen by around 13 basis points since the day before the budget, versus gains of 1 basis point and 3 basis points in the US and Germany, respectively (based on data from LSEG Datastream). Even better, and despite the relative decline in UK yields, sterling strengthened a bit over those three days (by 0.5% versus USD and by 0.3% versus EUR, according to Bloomberg data). That strengthening of the pound could partly explain why UK stocks didn’t seem to benefit.

Within the UK stock market, the actions not taken in the budget may have been more important than what did happen. In particular, the much feared windfall tax hike on banks didn’t materialise, which helped the sector continue outperforming the overall market (see Figure 1). As shown in the chart, UK bank stocks have tended to outperform the broad UK market when the yield curve steepens, as has been the case since early 2023. If the budget encourages the Bank of England to cut interest rates (because it contained nothing particularly inflationary), then I would expect bank sector outperformance to continue (I expect 75 basis points of BOE easing by end-2026).

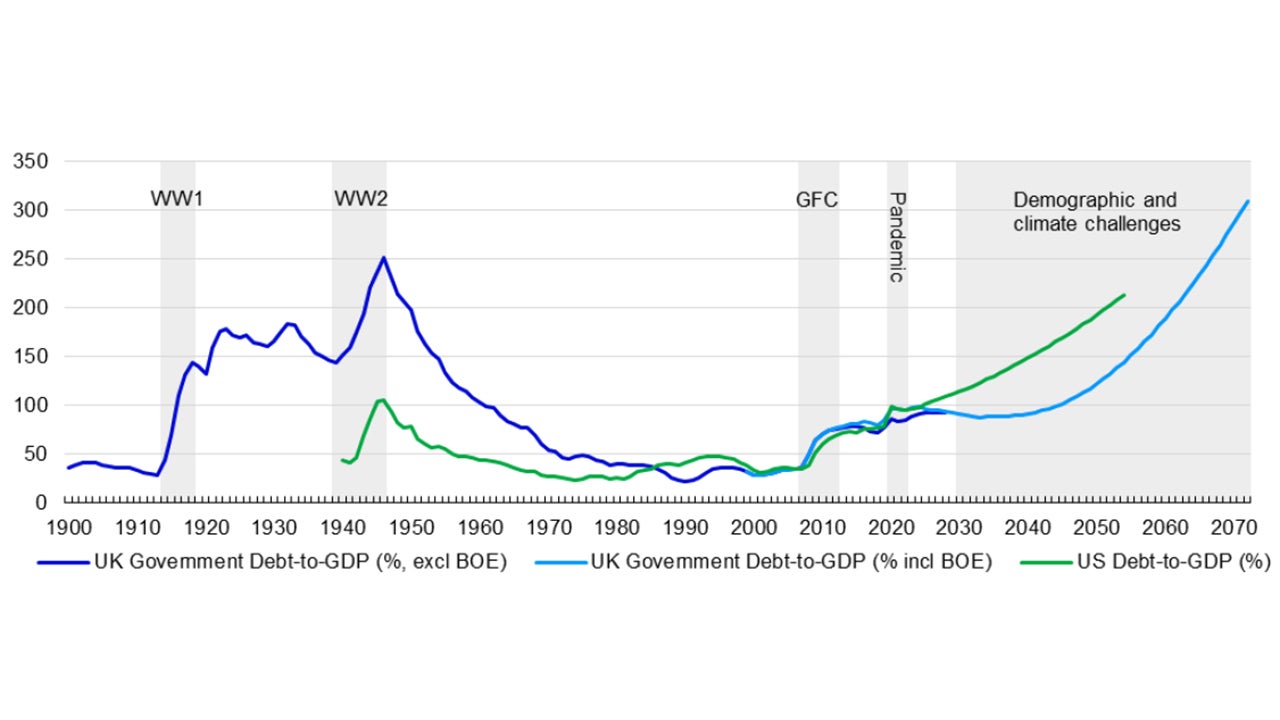

The UK government is receiving a lot of criticism about its lack of vision and ambition (from one side because of its “tax and spend” approach and lack of measures to boost the economy, and from the other because it is not spending enough on welfare etc.). In truth, I believe the government faces the unenviable task of trying to repair the fabric of the UK economy (infrastructure, healthcare, education etc.) while trying to keep government finances in reasonable order. Not only is the UK government’s net debt-to-GDP ratio already around 100%, but it is also expected to roughly triple over the next 50 years (according to OBR projections) under the pressure of demographic and climate challenges (see Figure 2). That would take the UK government debt-to-GDP ratio above the 250% seen at the end of the second world war.

Note: Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Based on monthly data from January 2008 to November 2025 (as of 28 November 2025). “UK Banks” is the FT All Share Banks index. “UK Yield Curve” is the 10-year UK gilt yield minus the UK treasury bill 3-month yield. Source: LSEG Datastream and Invesco Strategy & Insights

I suspect markets would judge that unsustainable, especially since Congressional Budget Office projections suggest US government debt is heading in the same direction (see Figure 2) and my own projections suggest other countries face the same dilemma (France, for example). This may explain why 30-year government yields have been trending upward this year. Unless governments get to grips with the problem (meaning less spending and/or more tax), I think the attraction of public sector debt may be diminished, perhaps meaning a long-term shift in strategic allocations toward private sector alternatives such as credit (both publicly quoted and private).

Concern about government debt may also help explain the strength of gold (the yellow metal is up 62% so far during 2025, based on Bloomberg data). Recent meetings in Europe and Asia suggest investors remain enthusiastic. However, they rarely mention government debt as a factor, focussing instead on central bank buying. That is interesting given that CBs bought 13% less gold in the first three quarters of this year than in the same period of 2024 (according to World Gold Council data). Likewise, jewellery demand has fallen 20%, while industrial demand is down around 1%. On the other hand, investment demand is up 87%, the big swing factor being ETFs, which have gone from outflows in the first three quarters of 2024 to sizeable inflows in 2025. It would appear that high prices are dampening all forms of demand except investment, which for the moment seems to be feeding on momentum.

Of course, governments would be helped by a growth boosting productivity miracle, which brings us to AI, another popular theme at recent meetings. For AI to turn into a productivity miracle, I believe we will need to see the benefits also accruing to adopters and not just enablers. A recent study by MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) suggested that AI could already perform the work associated with 11.7% of US jobs (see The Iceberg Index: Measuring Skills-centered Exposure in the AI Economy, October 2025). That sounds promising but an earlier MIT report suggested that 95% of adopters have failed to extract a measurable P&L impact, due to poor implementation (see The GenAI Divide: State of AI in Business 2025, July 2025). I suspect we will see productivity gains from AI but not the decades long uplift to growth needed to help governments.

Despite investor enthusiasm, the global technology sector has lagged basic resources and banks so far this year (see Figure 4) and performance among AI enablers has been variable. With that in mind, it was interesting to listen to Google CEO, Sundar Pichai, in a lengthy BBC interview, in which he suggested there was some “irrationality” in the AI boom and that, when it came to a potential bursting of the bubble, “no company is going to be immune, including us”. Whether there is a bubble or not, I suspect that limitations on AI-enabler share price performance will come from competition, over investment, physical limitations on data centres (see the effect of data centre cooling issues on recent CME trading activity) and, ultimately, from the next “big thing”. Imagine how disruptive it would be if quantum computing advances, thus reducing the need for hardware and data centres.

Unless stated otherwise, all data as of 28 November 2025.

Notes: Based on annual data from 1900 (1940 for the US) to 2072 (2054 for the US). In the case of the UK, the data is based on fiscal years (April to April), with 1900-01 labelled as 1900, for example. UK data is provided by the UK’s Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) and is taken from two reports (OBR Fiscal Risks and Sustainability July 2023 for the “excl. BOE” data prior to 1999 and OBR Economic and Fiscal Outlook March 2024 for the “excl. BOE” data from 1999 all the “incl. BOE” data). Note that the OBR has updated its forecasts since but has not provided the full set of data. In its Fiscal Risks and Sustainability Report July 2025 it suggested that debt-to-GDP would be above 270% in the early 2070s. US data is taken from the Congressional Budget Office, with the forecasts from 2025 on the basis that 2017 tax cuts will not be reversed. “GFC” is the global financial crisis.

Source: UK Office for Budget Responsibility, US Congressional Budget Office and Invesco Strategy & Insights

Investment risks

The value of investments and any income will fluctuate (this may partly be the result of exchange rate fluctuations) and investors may not get back the full amount invested.