Uncommon truths: Stuck on inflation

Recent data suggests inflation may be rising, bringing the risk of a “higher for longer” Fed. However, money supply, GDP and wage growth suggest the opposite should be true, while the Fed can do little against the recent narrow uptick.

US GDP data for the first quarter of 2024 seemed to reinforce recent market trends, with bond yields initially rising and share prices falling. GDP growth fell to 1.6% (quarter-on-quarter annualised), below consensus expectations of 2.5% (according to Bloomberg).

The most damaging aspect of the GDP report appears to have been the implied uptick in inflation, with core PCE (personal consumer expenditure) inflation rising to 3.7% (QoQ annualised), from 2.0% in each of the two previous quarters. Given the Fed’s focus on core PCE, this could further delay the first rate cut. Luckily, the monthly data released a day later was more comforting, with year-on-year (YoY) rates of 2.7% for headline and 2.8% for core.

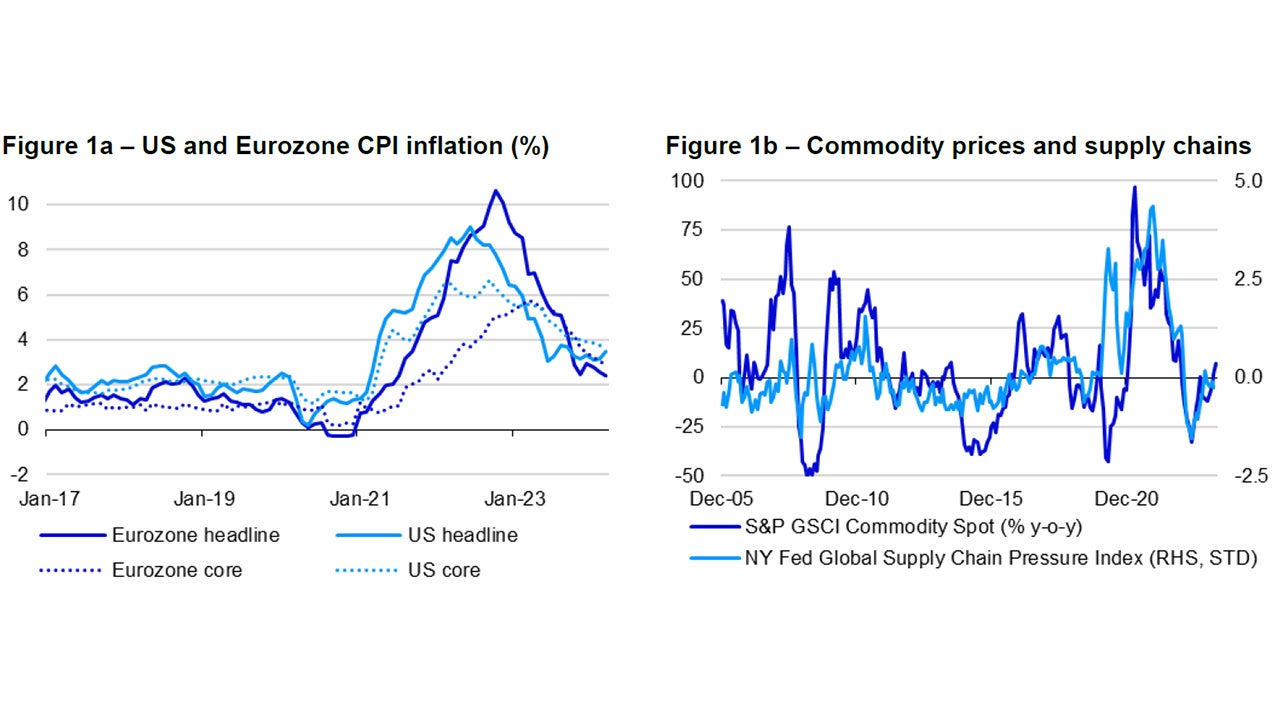

Beyond PCE, Figure 1a shows that US headline CPI inflation has been stuck in the 3%-4% range since June 2023 (the latest reading was 3.5% in March 2024), though the picture appears to be different in Europe, with Eurozone inflation still trending lower.

As an aside, there are important differences between the US CPI and PCE methodologies that can explain divergences (core PCE has been below core CPI for much of the last two years, for example). First, CPI covers only urban consumers, while PCE also includes rural consumers. Second, CPI measures what consumers pay, while PCE measures what producers charge, even if somebody other than the consumer is paying (health insurance, for example). Those considerations suggest PCE is wider based and more representative. Third, there are big differences in category weightings, particularly for housing (around 15% of PCE and 36% of CPI). Finally, they use different formulas to calculate changes: most importantly, CPI holds category weights constant (now for 12 months), while PCE refreshes the weights each month (hence, PCE captures changes in consumer behaviour, such as substitution to cheaper items, which is why it takes longer to publish).

CPI tends to be favoured by market commentators (probably because it is published earlier) and that is where I shall focus. Figure 1b hints at the reasons for the “stickiness” of inflation. First, commodity prices are no longer falling (the switch from big gains to sizeable declines since 2020 drove inflation up then down). Second, supply chain pressures drove inflation higher during the pandemic and reopening then helped drive it lower. Both these factors are now in “neutral” territory.

However, we have so far only considered headline CPI inflation, which is particularly susceptible to movements in commodity prices. After a period in which wages and core inflation were influenced by rapidly rising and then falling headline inflation, I suspect core inflation will now be the dominant driver of overall inflation.

Figure 1a suggests that core CPI inflation is trending lower in both the US and Europe, with inflation in the Eurozone now lower than in the US (which is the historical norm). The problem is that there appears to have been an acceleration in core CPI inflation in the first quarter of 2024 (core being CPI less food & energy). Indeed, annualising the gains in Q1 (March versus December) gives a US core inflation rate of 4.5%, rather than the 3.8% YoY rate in March.

Notes: Past performance is guarantee of future results. Figure 1a is based on monthly data from January 2017 to March 2024. Core indices exclude food & energy. Figure 1b is based on monthly data from December 2005 to April 2024 (as of 26 April 2024). NY Fed Global Supply Chain Pressure Index tracks the state of global supply chains using data from the transportation and manufacturing sectors, as constructed by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. It is shown as standard deviations from the historical mean. Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Global Supply Chain Pressure Index, S&P GSCI, LSEG Datastream and Invesco Global Market Strategy Office

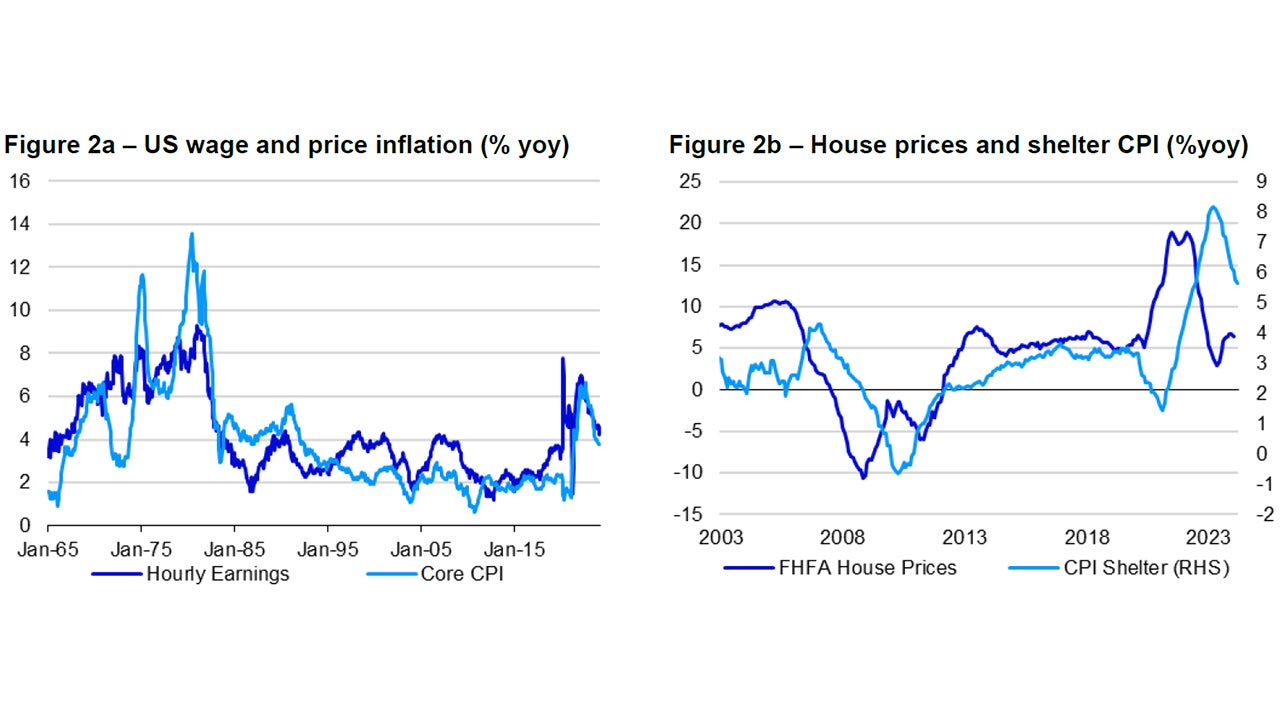

So, what are the drivers of core inflation and does the stronger Q1 data foretell of a rebound? In theory, wage growth should be a key driver, since labour costs are a large part of business costs. Figure 2a suggests a decent relationship between hourly earnings and core CPI in the US. The direction of causality is not always obvious (higher price inflation could encourage bigger wage gains) but with wage inflation on the decline, it is hard to imagine wages being a cause of higher inflation (especially since annualised wage growth in Q1 was only 3.8%, versus the 4.2% YoY gain in March).

Breaking down the US core CPI index into spending categories, I have focused on 12 major groupings that account for more than 98% of the overall index. Of these 12, only three had a YoY rate greater than the 3.8% core inflation rate in March 2024 (other goods & services, shelter and transportation services), the same number that had a rate below zero (household furnishings & operations, new vehicles and used cars and trucks). Indeed, if we use a symmetrical range around the 3.8% core rate, from 2.6% to 5.0%, the number of categories above the range was two (shelter and transportation services) versus nine below it.

The distribution of core inflation across categories is skewed to the downside but the dominant weighting of shelter (with an inflation rate of 5.7%) skews the overall rate upwards (shelter has a weighting of around 45% in the core CPI index). Shelter component inflation peaked at 8.2% in March 2023 and had fallen to 5.7% by March 2024 (CPI less food, energy & shelter inflation was 2.4% in March 2024, close to the Fed’s 2% target) So, what is the outlook for shelter?

Figure 2b suggests there is a lagged relationship between house prices and the shelter component (which is largely owners’ equivalent rent). The lag appears to be around 12-18 months, which suggests to me that shelter component inflation may continue to fall over the coming months and quarters (given what house price inflation was doing 12-18 months ago). Taking account of falling wage inflation and the lagged relationship with house prices, I would expect core CPI inflation to continue falling through this year.

So, why has core inflation picked up in the first quarter of the year? Looking at the detail of US core CPI, there were again only three groups with annualised 3-month inflation (December to March) above the core rate of 4.5% (shelter and transportation services were joined this time by medical care services), while four categories displayed negative inflation. Once again focusing on a symmetrical band around the core rate of 4.5%, only two groups had a 3-month annualised rate above 6.0% (shelter and transportation services), while eight had a rate below 3.0%. Once again, inflation seems biased to the downside when looking across categories and comparing to the average. However, the weighting of shelter skews that average upward.

Worse news is that seven of the 12 categories had a higher 3-month annualised rate in March than in December, so the worsening pattern seems more widespread. However, for three of those seven, the rate was still below 2.5%. Transportation services stands out, with a 3-month annualised gain of 16.7% (and a YoY rate of 10.7%). Within transportation services, the main culprit is motor vehicle insurance with a 3-month annualised 21.2% gain and a 22.2% YoY rate in March. I reckon that component alone added 0.8 percentage points to the US core inflation rate (YoY) in March. Whether the Fed can impact insurance premium rates that are governed by the prevalence of accidents, and repair and healthcare costs, is not clear. It could be argued that this element of inflation is beyond the control of the Fed and should therefore be ignored but that may be overly optimistic.

Notes: Past performance is guarantee of future results. Figure 2a is based on monthly data from January 1965 to March 2024. Figure 2b is based on monthly data from January 2003 to March 2024. Source: LSEG Datastream and Invesco Global Market Strategy Office

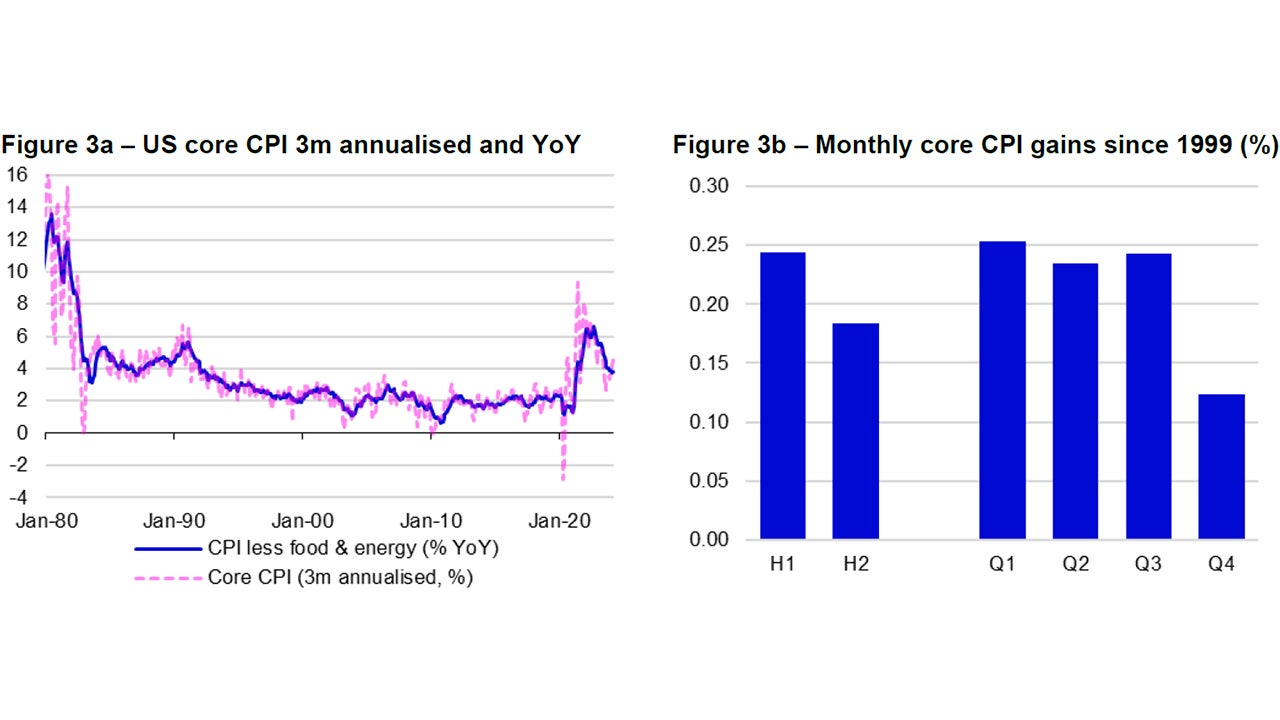

To summarise, it would appear that US inflation has ticked up in the first quarter of 2024 but that the pressures are in a limited number of groups, particularly shelter and motor insurance. Admittedly, the acceleration during Q1 was more broadly based, which brings us to reliability of 3-month annualised data. Figure 3a shows that 3-month annualised core CPI data is more volatile than the YoY data, which should be no surprise.

It is naturally worrying that the annualised rate has moved above the YoY rate, as it could suggest a new uptrend in the YoY rate of inflation. This is particularly concerning given the bout of inflation seen over recent years (and the obsession with the stickiness of inflation) but the chart suggests the annualised data is just too volatile to be relied upon as a forecasting aid. For example, the long downtrend in inflation in the 1990s came despite the 3m annualised rate being above the YoY rate on many occasions (likewise the downtrend from 2007 to 2010). Even when a downtrend has been interrupted (in late 1981, say), it was soon reestablished.

Further, Figure 3b suggests there may be some slight residual seasonality in US core CPI data. Despite being based on seasonally adjusted data; it appears to show that average monthly price gains tend to be higher in the first half of the year. Admittedly, the differences are small, though when looking at calendar quarters, it is interesting to see that price gains tend to be lower in Q4. Perhaps the data for 2023 Q4 made us too complacent and we may need to be patient for concrete evidence that the inflation trend remains downward.

Indeed, I believe the trend is downward, based on the weaker GDP data, the fact that wage inflation is falling and also that US money supply growth remains negative (as it has been since the end of 2022). I know the latter point tends to get ignored but it should be remembered that the spurt in US inflation came after M2 growth peaked at 27% in early 2021 and inflation then followed M2 growth lower. I believe that process is still working its way through the US economy.

But supposing I am wrong, and inflation trends higher, what would that imply for financial markets? Given that the inflation uptick doesn’t appear to be coming from a broad based increase in demand, the problem may be either cost-push in nature and/or focused on a few sectors. The Fed is not well armed to deal with either of those, so a policy of higher for longer could entail unnecessary economic damage. I suspect it would be very difficult to mitigate against such a scenario, with cyclical assets vulnerable, while fixed income assets would have to further adjust to Fed rates staying at current levels or even rising. Within the Model Asset Allocation shown in Figure 7, the Overweighting in cash and bank loans could mitigate against higher rates and I would also have to consider gold and inflation protected government bonds (especially in the US) as alternatives (under that scenario).

However, I remain confident that the inflation trend is downward, based on money supply, economic growth and wage trends. The recent uptick in inflation seems too narrowly based to be indicative of a demand driven trend and using annualised 3-month data is a perilous enterprise. Patience is key. I only hope the Fed is paying attention to the underlying detail and focusing on what it can control. Otherwise it will continue with the higher for longer policy (and risk another policy error) with all that entails for the economy and markets.

Unless stated otherwise, all data as of 26 April 2024

Notes: Figure 3a is based on monthly data from January 1980 to March 2024. Figure 3b shows the average monthly gain in the US core CPI index in various parts of the calendar year from April 1999 to March 2024. It is based on seasonally adjusted indices.

Source: LSEG Datastream and Invesco Global Market Strategy Office