Uncommon truths: Tariff pain relief but not the full cure

The US-UK trade deal gives hope that the full pain of the “Liberation Day” tariffs can be avoided. But tariffs are likely to remain higher than at the start of the year, which may be bad news for US stocks.

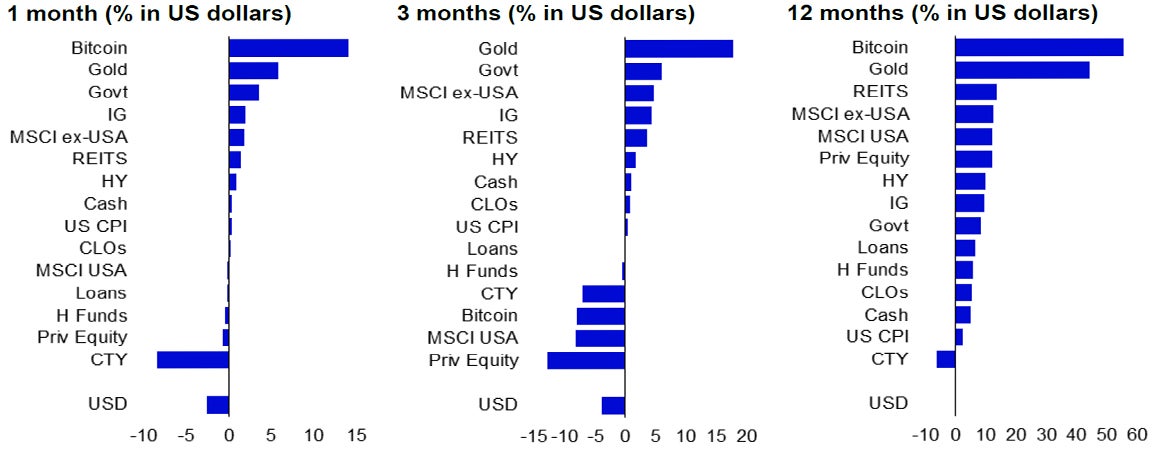

A lot may have changed since the start of the year, but financial markets only partially reflect that. Figure 1 shows that in April defensive assets such as government bonds and investment grade credit outperformed more cyclical assets such as commodities and private equity. However, major stock markets and high yield credit hardly suffered. Despite the initial panic after the 2 April 2025 “Liberation Day” announcement, markets appear to have shrugged off those concerns, with many stock markets up a lot in the last month (see Figure 3).

Even better, the US-UK trade deal gives hope that the US is now rowing back on some of the most disruptive elements of its reciprocal tariff regime, especially since President Trump also mentioned the possibility of a deal with the EU and reduced tariffs on China if talks go well during the weekend of 10 May 2025.

- The main points of the US-UK deal were as follows:

- US tariffs on most UK goods will remain at 10%.

- The US tariff on UK cars will be reduced to 10%, up to a limit of 100,000 cars and 25% thereafter (it had been increased to 27.5% earlier in the year).

- The US tariff on UK steel and aluminium will be reduced to zero (it had been set at 25%).

- The US tariff on engines and plane parts from Rolls Royce will be zero.

- Reciprocal access for beef, with UK farmers given a tariff-free quota of 13,000 tonnes.

- UK tariffs on US ethanol will be reduced to zero.

- The UK will reduce non-tariff barriers to a range of US products including beef, ethanol, machinery and chemicals.

The US-UK deal was far from “full and comprehensive”. My calculations (based on UK trade data for 2024) suggest it covers 23% of UK exports to the US (at most) and 35% of US exports to the UK (again on a generous interpretation). The US may have more to gain in the sense that reductions in non-tariff barriers in some areas could boost exports to the UK but, in 2024, goods exports to the UK were only 3.9% of total US goods exports and 0.3% of US GDP (according to US trade data for 2024). On the other hand, UK goods exports to the US were 16% of UK goods exports (or 2.1% of UK GDP).

However, I think the real benefit to financial markets comes not from the details of the deal but rather what it symbolises. It seems to indicate a US willingness to find ways to keep tariffs below those announced on 2 April. In my opinion, the further the US can row back from those reciprocal tariffs, the less will be the damage wrought upon the US economy.

Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Based on monthly total return data for global assets in US dollars up to 30 April 2025. Abbreviations are as follows: “CTY” is commodities, “Govt” is government debt”, “H Funds” is hedge funds, “HY is high yield credit, “IG” is investment grade credit, “Loans” is bank loans or leveraged loans, “MSCI ex-USA” is MSCI ACWI ex USA Index, “Priv Equity” is private equity, “CLOs” is AAA collateralised loan obligations, “US CPI” is the US Consumer Price Index and “USD” is a trade weighted US dollar index. See appendices for definitions of asset categories and sources.

Source: Bank for International Settlements, ICE BofA, Credit Suisse/UBS, GPR, JP Morgan, MSCI, S&P GSCI, LPX, Bloomberg, LSEG Datastream and Invesco Global Market Strategy Office

Needless to say, all countries that negotiate similar deals with the US will benefit (or suffer less than otherwise) but I think the US will be the biggest beneficiary, as I always believed it had the most to lose. In particular, I think that countries such as Vietnam and Cambodia have a lot to gain, given the importance of trade with the US to their economies (see Who will suffer most from US tariffs?). Though China isn’t as exposed to the US, it also has a lot to gain because of the extremely high tariffs imposed upon it (and largely reciprocated by itself).

However, let’s not pretend that everything is going back to square one. As the UK deal revealed, 10% may have become the new baseline for tariffs. Though some elements of the UK deal will give hope to other countries (zero tariffs on steel and aluminium and 10% tariffs on cars), it is not clear that all countries will win the same concessions (the UK is not a big player in those sectors); 10% seems the best that can be hoped for. Based on recent comments from President Trump, China may not even be that lucky (ahead of the first talks, he said that 80% felt right for tariffs on China).

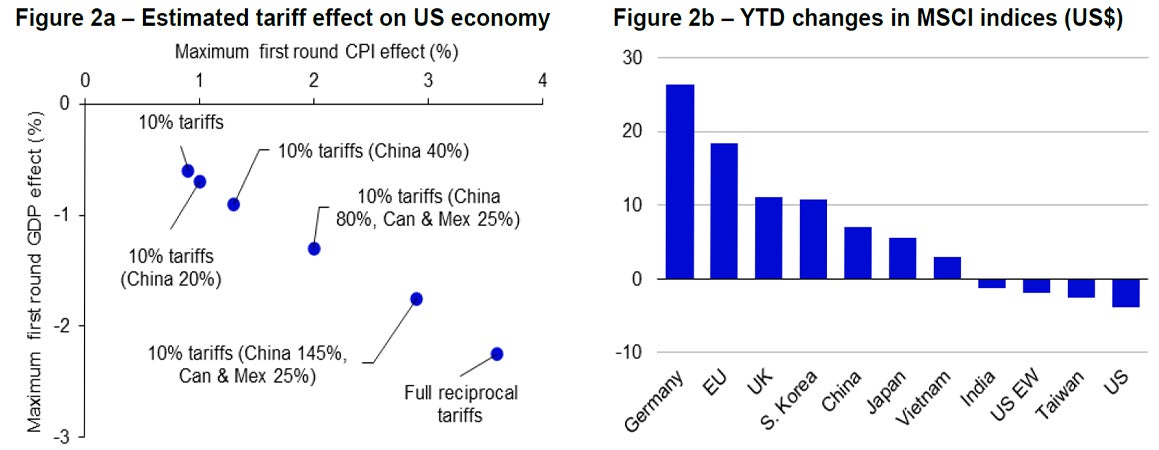

Figure 2a shows my own estimates of the maximal first round impact on US CPI and GDP under various scenarios. If the full reciprocal tariffs were imposed, I reckon the consumer price index could receive an initial uplift of up to 3.5% and that GDP would be reduced by around 2.25% (in the first instance). The risk of recession under that scenario is real, in my opinion. As suggested in the chart, the lower the tariffs, the less the economic impact. However, even with a uniform 10% tariff there would still be an effect, with the consumer price index rising by 0.9% and GDP down by 0.6%. I suspect more damage than that is already baked in because of the extreme tariffs now imposed on China and the uncertainty of recent weeks.

Figure 2b shows how stock markets have performed since the start of the year (in US dollars to capture the effect of currency movements). Though the ranking is roughly what I would expect (US suffering more than others; Germany, UK and EU benefitting from the promise of a fiscal boost), I think the decline in US stocks underestimates the potential economic damage, especially if tariffs on China remain at 40% or above.

In conclusion, the US-UK trade deal gives hope that we can move away from the potentially very damaging full reciprocal tariff regime. I wish that my Model Asset Allocation (Figure 6) had not been Overweight industrial commodities but at least a relief rally may be starting (see Figure 3). The above analysis suggests to me that it is too soon to boost the allocation to US equities, given how expensive I thought they were at the start of the year (I am happy to remain Underweight the US market, in favour of Europe, China and emerging markets). Likewise, I am happy to remain underweight the US dollar.

Note: Figure 2a: There is no guarantee that these views will come to pass. “Can” is Canada and “Mex” is Mexico. “Maximum first round CPI effect” assumes that 100% of new tariffs are passed on in the form of higher import prices and using the assumption that a rise of 10% in import prices leads to a 1% rise in the US consumer price index (based on research conducted by the US Federal Reserve1). “Maximum first round GDP effect” shows our estimate of the immediate effect on US GDP from the squeeze in real incomes and profits that comes from higher import prices, without allowing for multiplier effects etc. “Full reciprocal tariffs” is based on the rates announced on or before 2 April 2025 (including zero for USMCA imports from Mexico and Canada) and the subsequent 145% rate for China. Other scenarios assume 10% tariffs for all countries on all products, with exceptions shown in parenthesis. The exceptions for Canada and Mexico apply only to imports not covered by the USMCA agreement between the US and those countries (in 2024, around 56% of combined imports from Canada and Mexico were not covered by USMCA). Figure 2b: past performance is no guarantee of future results. It shows year to date changes in MSCI equity indices in US dollars, as of 9 May 2025. “S. Korea” is South Korea. “US EW” is the MSCI USA Equal Weighted index. “YTD” is year to date. Source: MSCI, LSEG Datastream and Invesco Global Market Strategy Office.

All data as of 9 May 2025, unless stated otherwise.

Investment risks

The value of investments and any income will fluctuate (this may partly be the result of exchange rate fluctuations) and investors may not get back the full amount invested.