Uncommon truths: The sustainability of US debt and gold

I believe US government debt is unsustainable on current trends. That could be changed by a mix of reduced primary deficits, stronger GDP growth and lower interest rates. If the difficult choices are not made, I think gold could be ever more attractive.

We have recently seen examples of the US dollar falling at the same time that treasury yields have risen. I reckon this could be due to concerns about the ability of the US to finance itself when markets lose faith in the Fed. There are many strands to this, including White House pressure on the Fed to cut rates, but I think the basic problem is excessive debt.

Bank for International Settlements (BIS) data suggests that credit to the US non-financial sector was 252% of GDP in 2024 Q3 (compared to 189% at the end of 1999). A decent portion of US liabilities are held by overseas investors, as evidenced by a net international investment position of -90% of GDP in 2024.

Of course, the main focus is upon government debt. The US Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that the general government net debt to GDP ratio was 98% at the end of 2024. The gross debt to GDP ratio was 122% (slightly above where it was at the end of the second world war according to our calculations based on data from Global Financial Data). In the CBO’s long term projections, those ratios are projected to rise to 156% and 169%, respectively, by 2055. Even worse, the CBO also estimates that if the 2017 tax cuts were not reversed in 2025 as planned (and some other revenues were lower), the net debt to GDP ratio would be 220% in 2055 (versus 156% otherwise).

Even without the extension of the 2017 provisions, those are enormous debt to GDP ratios, taking them well beyond anything seen in the history of the US (the previous peak came in 2020 when the gross debt to GDP ratio briefly exceeded 132%, according to OECD data). It would also take US government debt far beyond what economists used to think was sustainable (I used to think 80% of GDP was the ceiling). Perhaps sustainability is better judged by net interest costs as a share of GDP. The CBO suggests that ratio will be 3.2% in 2025, rising to 5.4% by 2055 (or 8%-9% if the 2017 tax cuts are not reversed, according to my calculations). CBO data suggests the highest post-war interest cost to GDP ratio was 3.2% (in 1991).

Unfortunately, I consider some of the CBO’s assumptions to be optimistic. For example, the primary budget deficit is expected to be below 2% in most years to 2055, while the average since 2000 has been 3.0% (it has rarely been below 3% during the Trump and Biden administrations). Further, the average interest rate on debt is expected to peak at 3.6%, while between 2001 and 2007 it was between 4.5% and 6.6% (though lower cost inflation protected bonds were then a smaller part of the total).

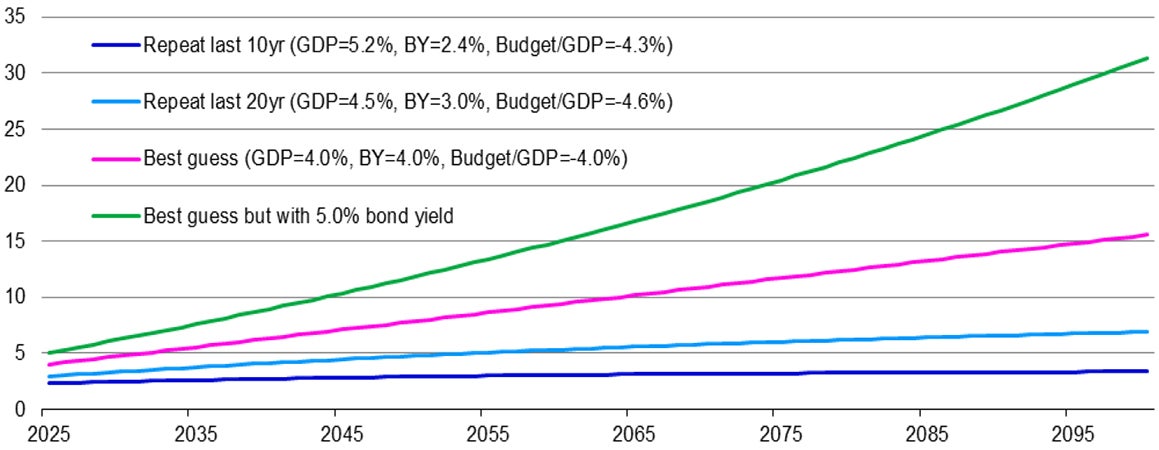

Figure 1 shows my own projections of the future path of the net interest to GDP ratio. I consider a number of scenarios that are differentiated by the assumptions about the primary budget deficit, nominal GDP growth and the average interest cost of debt.

Note: Annual data from 2025 to 2100. Projections are based on a starting point of the net general government debt to GDP ratio in 2024 (using OECD data), with future debt to GDP depending on assumptions about primary budget deficits, nominal GDP growth and the average interest rate on US government debt (historical data provided by the US Department of the Treasury). “GDP” is nominal GDP growth. “BY” is bond yield (or assumed average interest rate on outstanding debt). “Budget/GDP” is the primary budget balance (i.e. before interest costs) divided by GDP. “Repeat last 10yr” is a scenario where all parameter values are in line with the average of the last 10 years. “Repeat last 20yr” uses the averages of the last 20 years. “Best guess” is our best guess of the future parameter values. For reference the US Congressional Budget Office estimates the net interest to GDP ratio will be 3.2% in 2025. These views may not come to pass. Source: OECD, US Department of the Treasury, US Congressional Budget Office, LSEG Datastream and Invesco Global Market Strategy Office.

The closest to the CBO’s baseline scenario (in terms of 2055 outcomes) is the one that uses parameter values based on the average of the last 20 years. Under this scenario, net debt to GDP would be 171% in 2055 (156% under the CBO baseline) and net interest costs would be 5.1% of GDP (3.6% under the CBO baseline). Net debt to GDP would then rise to 232% in 2100, with net interest costs at 6.9% of GDP. This would be almost unprecedented for a stable developed economy (there was a brief 15-year period from 1983 when Italy’s net interest cost to GDP ratio exceeded 6.9%, according to OECD data).

Unfortunately, I think a scenario based on the last 20 years is too optimistic. First, I expect nominal GDP growth to be lower over the coming decades, as a result of less favourable demographics (in my “Best guess” scenario, I assume 4.0% growth rather than the 20-year average of 4.5%). Second, I believe the average interest cost of debt will be higher than in the last 20 years (I assume 4.0%, rather than the 20-year average of 3.0%). Offsetting those factors, I assume the primary budget deficit will be an average of 4.0%, versus a 20-year average of 4.6%. This “Best guess” scenario envisages that by 2055 net debt will be 216%of GDP and that net interest payments will be 8.6% of GDP. That is very close to the 220% and 8%-9%, respectively, implied by the CBOs alternative scenario under which the 2017 tax cuts are not reversed.

Unfortunately, it doesn’t stop there. My “Best guess” scenario suggests that debt/GDP will be 389% in 2100, with net interest/GDP at 16% and rising. That sounds unsustainable to me. Even worse, I fear that bond yields would rise even more under such a scenario. Hence, the final scenario in Figure 1 shows what happens if we assume the “Best guess” scenario but with an average interest rate on government debt of 5%, rather than 4%. In this case, debt/GDP would be 627% in 2100 and net interest/GDP would be 31%.

Neither the “Best guess” nor the “Best guess with 5% bond yield” scenarios sound sustainable to me. So, how could such outcomes be prevented? First, the US government could reduce the primary deficit by reducing spending (DOGE exercise, for example), increasing revenues (raising tax rates, for example) or boosting real GDP growth (immigration, deregulation and/or measures to boost productivity). Second, nominal GDP growth could be boosted by encouraging inflation, though in my opinion that would cause an offsetting rise in bond yields. Third, financial suppression could be made a permanent feature, with the Fed expanding its balance sheet to effectively buy all treasury bonds, though that could imply loss of control of the financial system. Finally, the US government could renege on its debt but I think that would make the situation even worse.

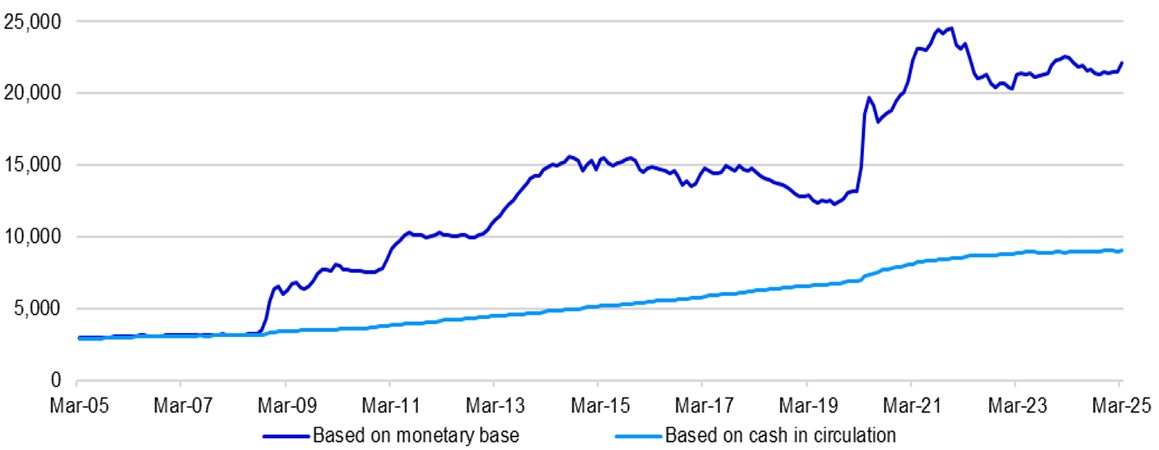

I think the only viable solution is for the US government to do less (cut spending), create more revenue (raise taxes), improve demographic trends via immigration and keep interest rates low. A combination of raising nominal GDP growth to 5%, limiting the primary budget deficit to 2% and the average cost of debt to 3% would stabilise debt. However, none of that would be easy, so we need to consider what happens if the difficult choices are not made. One obvious outcome could be a radical shake up of the financial system, which is where the idea of a return to the gold standard comes from. Figure 2 shows the price of gold required for US gold reserves to fully back US notes and coins in circulation ($9,051 per ounce, as of March 2025) or the monetary base ($22,085). Gold is up a lot and I think it is expensive but this sort of analysis could be one reason why it is becoming more popular.

Note: This is a theoretical simulation and there is no guarantee that these views will come to pass. Monthly data from March 2005 to March 2025. The chart shows the price of gold that would equate the value of official US gold reserves to the value of cash in circulation or the monetary base (cash in circulation plus bank reserves at the Fed). Source: LSEG Datastream and Invesco Global Market Strategy Office.

All data as of 25 April 2025, unless stated otherwise.

Investment risks

The value of investments and any income will fluctuate (this may partly be the result of exchange rate fluctuations) and investors may not get back the full amount invested.