Uncommon truths: The UK is not alone when it comes to fiscal problems

The UK government is under a lot of pressure, not least in the budgetary realm. With an OBR forecast that net debt will be above 270% of GDP in the early 2070’s, the situation looks dramatic. Our own forecasts suggest the UK is not alone and that many governments will struggle to avoid such debt ratios as populations decelerate and age.

The UK media and many commentators are downbeat about the prospects for the UK economy, the fiscal situation and the outlook for UK debt. This stems partly from the fact that the UK has seen little economic growth over recent years. For example, since the end of 2019, the UK economy has grown by only 4.5% (up to 2025 Q2). This may be better than the 0.1% seen in Germany but is around one-third of the 13.3% in the US and well below the 35.4% and 30.5% seen in India and China, respectively.

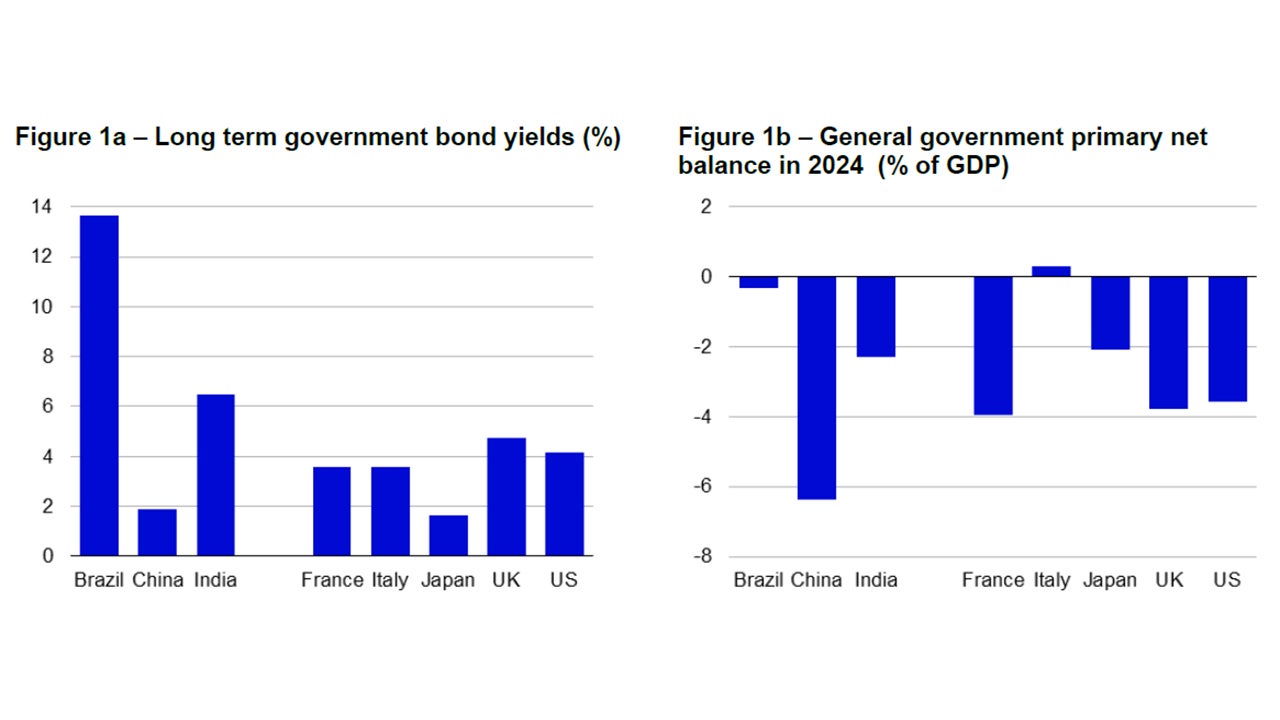

It also seems to be the result of inflation remaining stubbornly above the Bank of England’s 2% target, with CPI inflation of 3.8% in August (up from a low of 1.7% in September 2024). This is preventing the BOE from cutting rates as rapidly as the ECB, with the BOE policy rate at 4.00%, while ECB’s Deposit Rate is 2.00%. That may explain why gilt yields remain so elevated, with the 10-year yield around 4.74% versus a 10-year bund yield of 2.73%, a 10-year French yield of around 3.55% and a 10-year US yield of 4.15% (all as of 26 September 2025). Figure 1b shows the comparison with a range of countries that will feature in this report.

However, elevated UK yields may also be due to concern about the fiscal situation. The budget will be announced on 26 November and there is much speculation about how Chancellor Reeves will fill the fiscal hole that seems to be widening. For example, the cumulative public sector net borrowing requirement for the current fiscal year was £83.8bn in August 2025, £16.2bn higher than the year earlier period and £11.4bn above the monthly profile consistent with the Office for Budget Responsibility’s (OBR) March forecast (the UK fiscal year starts in April). The problem seems to be more a shortfall of receipts versus forecast (largely VAT), than excess spending.

The Chancellor’s self-imposed fiscal rules (that budget forecasts should predict that by 2029/30 the day-to-day budget, excluding investment spending, should be in surplus and that net debt/GDP should be falling) and electoral promises not to increase income tax, employee national insurance contributions nor VAT. Having already been forced to reverse her attempts to cut various forms of spending, Rachel Reeves is left trying to find extra sources of tax revenue. A 30-year gilt yield above 5.50% may suggest market scepticism on that front.

With the UK government’s net debt-to-GDP ratio hitting 96.4% in August (according to the Office for National Statistics), just how bad is the debt outlook for the UK and how does it compare to elsewhere. The first item of bad news is that the OBR’s latest Financial Risk and Sustainability Report (July 2025) envisages that UK government debt will be above 270% of GDP by the early 2070s (under pressure from an ageing population, which adds to state healthcare and pension costs, the impact of climate change and other factors). Another problem is that Figure 1b shows that the UK government’s primary deficit is among the largest among our sample of countries.

Note: Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Left chart shows 10-year government bond yields as of 26 September 2025 (from Bloomberg). Right chart shows the primary net balance, which is the budget balance excluding interest costs, as estimated by the IMF (or OECD for the US).

Source: IMF, OECD, Bloomberg, LSEG Datastream and Invesco Global Market Strategy Office.

To be fair to the UK, few governments offer 50-year forecasts. The US Congressional Budget Office (CBO) issues a 30-year forecast. In a letter sent to Congress in March 2025, the CBO baseline estimate was that US government net debt will be 166% of GDP in 2054 (up from 102% in 2025). However, under an alternative scenario that allows for the non-reversal of 2017 tax cuts, the CBO estimates that net debt-to-GDP will be 214% in 2054 (those tax cuts will not be reversed under the new budget). So, the US debt situation seems as precarious that of the UK.

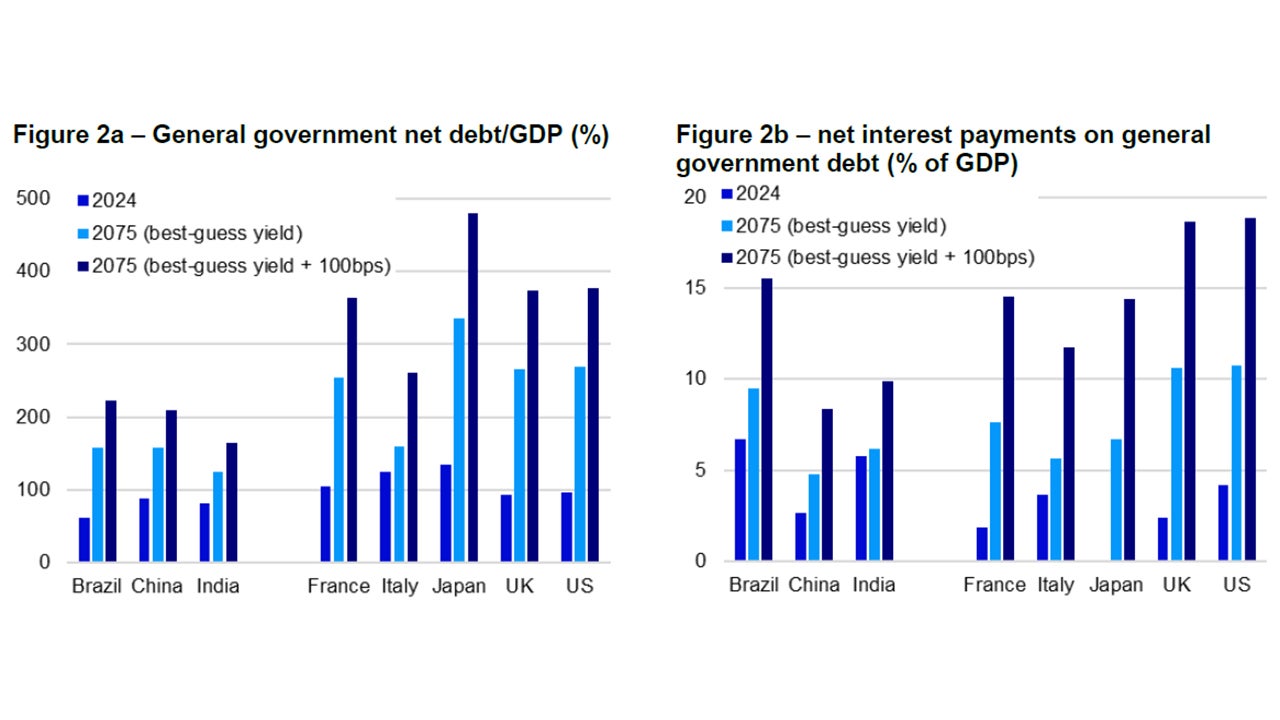

That is confirmed by my own calculations out to 2075, the results of which are shown in Figure 2a. My calculations use a simple approach that assumes constant annual growth in nominal GDP, constant primary budget deficits and constant government bond yields. For each country, my forecasts allow for possible demographic effects on GDP growth, primary budget deficits and bond yields (see the appendices for those assumptions).

The first point of note is that the developed economies shown in Figure 2a had higher debt-to-GDP ratios in 2024 than the chosen emerging economies. My forecasts suggest that will still be the case in 2075 (see “best guess yield” forecast). Among developed countries, Japan’s debt-to-GDP ratio is predicted to be 334% in 2075 (up from 135% in 2024). The 2075 projection for France is 254% and that for the US is 268% (or 198% in 2054, versus the CBO estimate of 214% for that year). The forecast for the UK in 2075 is 265%, close to the OBR estimate that it will be above 270%.

Perhaps the most interesting country is Italy, with the debt-to-GDP ratio predicted to rise from 125% in 2024 to “only” 160% in 2075. The reason for this relatively limited growth in debt is found in Figure 1b, with Italy’s primary budget (the balance before interest costs) in surplus in 2024, as it has been in all but six years since 1992. That makes an enormous difference to the debt path and shows other countries how to get their debt under better control. Improving the primary budget balance requires higher taxes and/or lower spending, which is easier said than done, especially as populations decelerate and age.

When it comes to debt sustainability, the important ratio is net interest payments-to-GDP (see Figure 2b). The low interest rates since the Global Financial Crisis mitigated the effect of rising debt on interest costs. For example, despite Japan having the highest debt ratio in 2024, its net interest-to-GDP ratio was virtually zero. However, interest rates have risen in most countries and that will boost those interest cost ratios over the coming years (see the 2075 “best-guess” forecasts). My projections suggest UK and US net interest-to-GDP ratios will be above 10% in 2075 (versus 2% and 4%, respectively, in 2024). Even worse, if investors demand higher yields to absorb more government debt, the path of debt-to-GDP will steepen and interest costs-to-GDP could approach 19% in both the UK and the US (if yields rise by 100 basis points). I doubt that is sustainable.

The UK may be in a fiscal bind but it is not alone.

Unless stated otherwise, all data as of 26 September 2025.

Notes: Figure 2a shows general government net debt-to-GDP ratios (*except for China and India where net debt is not available, so gross debt is used). 2024 ratios are as estimated by the IMF. “2075 (best-guess yield)” is Invesco’s estimate of the debt ratio in 2075 based on where we think government debt yields will be, along with assumptions about nominal GDP growth and primary balance/GDP ratios (all variables are held constant throughout the forecasting period). “2075 (best-guess yield + 100bps)” adds 100 basis points to the best-guess yield to show the ceteris paribus impact of a rise in yields. Figure 2b shows net interest payments on government debt as a percent of GDP (China and India are based on gross, rather than net debt). The 2024 interest payment data is provided by the IMF, except for Brazil, China and India which are our own estimates. There is no guarantee that these views will come to pass.

Source: IMF, OECD, LSEG Datastream and Invesco Global Market Strategy Office.

Investment risks

The value of investments and any income will fluctuate (this may partly be the result of exchange rate fluctuations) and investors may not get back the full amount invested.