Uncommon truths: What is driving gold?

Gold recently touched a new high in real terms, despite yields and the dollar rising. Central banks and worry about geopolitical/economic instability may be at work. But prices can’t rise forever.

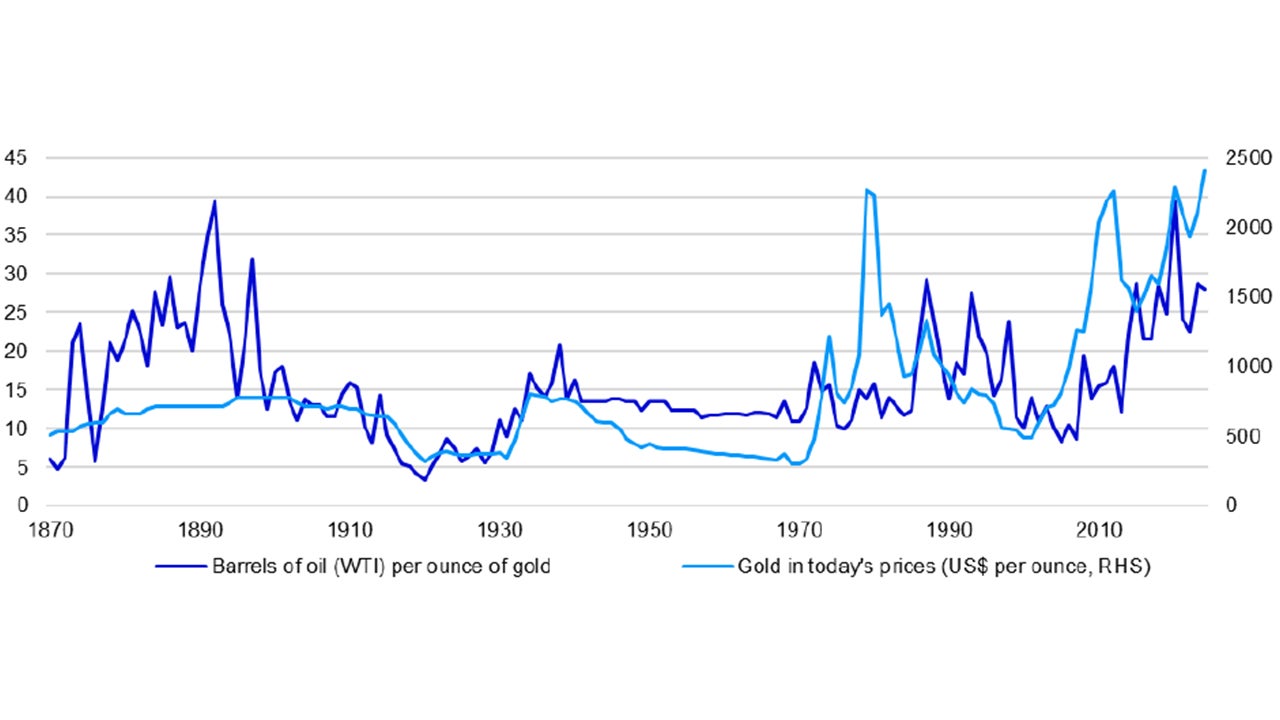

Item #7 on my list of 10 surprises for 2024 was that geopolitics could push Brent above $100 and gold above $2350 (see The Aristotle List). Though Brent has struggled to go above $91, gold this week touched $2430 (having started the year at $2063). Figure 1 shows that gold has reached a new high in real terms (deflated by US consumer prices) and is also elevated when measured in barrels of oil per ounce of gold.

It used to be easy to explain movements in the price of gold. A simple model based on the real 10-year treasury (TIPS) yield, the 10-year inflation breakeven and the trade weighted US dollar did a pretty good job. However, that has not been the case for a few years. Indeed, gold has recently risen despite higher treasury yields and a stronger dollar. What’s going on?

The first interesting change in behaviour occurred at the time of the financial crisis. Prior to that, the coefficient on inflation expectations within my econometric model was positive. Gold tended to rise when inflation breakevens were rising, which fits with the idea of gold mitigating against inflation. However, after the financial crisis, the coefficient on inflation expectations switched to negative (as were already those on real yields and the dollar). Gold was then tending to fall when inflation expectations rose, perhaps because investors were buying gold out of fear of deflation (and financial system collapse).

The second notable change came when Donald Trump was elected president of the United States. In November 2016, gold moved to a sizeable premium to the fair value indicated by my model. Introducing a dummy variable solved the problem, with a coefficient that suggested the “Trump premium” was around $230. I guessed gold was being purchased out of fear of the geopolitical consequences of a Trump presidency.

Everything was then OK until 2022. Gold started that year at $1822 and my model was suggesting the price should have been $1706 (that gap was not worrisome). Inflation was on the up and inflation breakevens were starting to climb, but a 10-year TIPS yield of -1.1%, supported the estimated fair value of gold. Then inflation rose further (as did inflation expectations) and central banks starting tightening. Bond yields rose sharply (the 10-year TIPS yield was 1.5% at the end of 2022) and the dollar strengthened. Taking all of that into account, my model suggested gold should have fallen to around $850 by year-end (even allowing for the Trump premium, despite the fact he was no longer president). Instead, gold was at $1815, virtually unchanged versus a year earlier.

Clearly, something had changed. Perhaps buyers had been jolted into the old habit of buying gold when inflation rose. However, assuming a reversion to the pre-2007 model would have still seen the fair value of gold fall by 25% during 2022. Higher inflation may have helped but that would have been overpowered by the drag from rising real yields and a stronger dollar.

Though gold was virtually unchanged between the beginning and end of 2022, it did rise quite sharply at one stage – peaking at $2050 on 8 March 2022 (up 14% since 28 January). The move coincided with the mobilisation of Russian troops and eventual invasion of Ukraine. Geopolitical concerns were perhaps behind that rally in gold, which came despite imminent Fed tightening. By the end of April 2022, the 10- year TIPS yield had strayed into positive territory, the 10-year breakeven inflation rate was 2.88% and the trade weighted dollar had strengthened 3% year-to-date. Nevertheless, gold only fell to $1909 (by end-April), while my model suggested a fair value below $1300.

Note: Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Annual data from 1870 to 2024 (as of 12 April 2024). Gold is expressed in today’s prices using an index of US consumer prices. Both oil and gold are based on spot prices.

Source: Global Financial Data, LSEG Datastream and Invesco Global Market Strategy Office

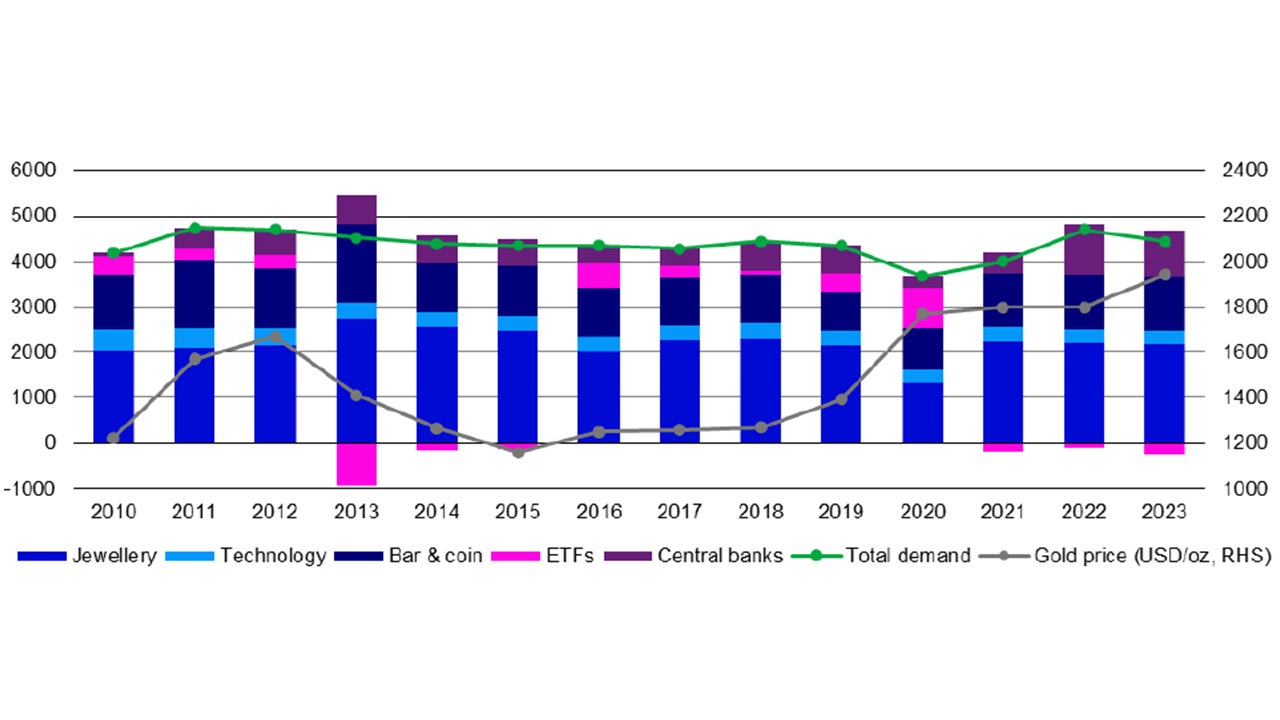

It was around this time that central bank purchases increased and that seems a plausible explanation for the strength of the yellow metal, despite rising yields and a stronger dollar. Figure 2 shows that demand for gold increased 17% in 2022 and was higher than in any year since 2012 (based on World Gold Council data). This was partly due to a 4% increase in the demand for bars and coins but was largely because central bank purchases more than doubled (accounting for more than 90% of the increase in total demand).

Central banks purchased 1,082 tonnes of gold in 2022, well above the previous post-2010 peak (656 tonnes in 2018). Though purchases started to increase in the second quarter of 2022, they really picked up in the second half of the year. Purchases in both the third and fourth quarters were well above anything seen in any quarter since the start of 2010 and total purchases in the second half of 2022 were nearly 7-times the year earlier level. It is broadly assumed (though we can’t be sure) that a lot of those central bank purchases came from Russia, as it tried to rapidly diversify its reserves away from US dollar financial assets to avoid sanctions (so geopolitics were playing a role). The strength of central bank purchases seem to explain the rise in demand for gold in 2022 (when supply increased by around 1%), and therefore the relative stability of the price despite the financial backdrop.

However, total demand eased by 5% in 2023 (while supply increased by 3%). In fact, there was less demand from all the sources shown in Figure 2, including a 4% drop in central bank purchases. This didn’t hold back the price -- it increased by 14% during the course of 2023. Incredibly, much of that increase came in the fourth quarter of the year, despite central bank purchases being 40% below the year ago level (purchases during H2 were down 30% on 2022 H2).

Central bank purchases, though still sizeable, lost momentum during 2023, and seem unable to explain gold’s continued rise (especially given that supply seemed to outstrip total demand). Further, the general backdrop (real rates and dollar) continued to be a negative factor during 2023, although it did turn supportive during Q4 (my model suggests the price should have fallen by 2% during 2023).

So, what was driving the price gains in 2023? Perhaps during the fourth quarter it was geopolitical concerns, following the 7 October attack by Hamas on Israel (gold had fallen to $1820 prior to the attack). Indeed, most of the Q4 price gain happened during October, despite rising real yields and a strengthening dollar. In the absence of full demand data, it seems similar concerns may also explain the 14% price gain so far in 2024 (or 18% since the low on 14 February 2024), especially with rates and the dollar again rising.

Interestingly, Figure 2 shows that gold ETF flows have been negative in the last three calendar years. Indeed, flows were positive in only two out of those twelve quarters. According to World Gold Council data, those ETF outflows continued in the first two months of 2024 and, if anything, accelerated versus 2023 Q4. So, ETF flows seem to have followed the expected pattern over recent years, when considering the rise in bond yields and the dollar. That may suggest that professional investors are behaving as my model would suggest (assuming they are users of gold ETFs).

Note: Annual data from 2010 to 2023. Total demand is the sum of the categories shown in this chart but doesn’t equal supply as the balancing item (often called “OTC and other” and used to make demand equal supply) is not shown. Gold price is the annual average LBMA gold price. Data is sourced from the World Gold Council Global Demand Trends.

Source: World Gold Council, ICE Benchmark Administration, Metals Focus, Refinitiv GFMS and Invesco Global Market Strategy Office

However, that offers no explanation for the sharp rise in gold over recent months. Unfortunately, we do not yet have the central bank data that could help us understand if they have again accelerated their purchases (I’m not sure why they would have). As for the other big sources of demand, I think it unlikely that jewellery demand would surge, given the rise in prices (if anything I would expect the opposite).

On the other hand, I think the demand for bars and coins (the second largest source of demand in recent years behind jewellery) could be rising if retail investors expect the recent price surge to continue (in a self-reinforcing speculative bubble). This would be reminiscent of what happened in the late-1970s/early-1980s and during the financial crisis, when queues formed outside gold suppliers. Now that Costco is selling gold bars online, it has become even easier for the retail investor to get involved. Possible drivers of demand could be geopolitical concerns, worries about US government debt (and future inflation) and arbitrage away from Bitcoin (currently above $86,000).

The notion that speculative demand is fuelling the price rise is supported by World Gold Council data showing that open interest on the nine major global gold futures exchanges is at a record high (as of 5 April 2024), and has been for the last month or so.

Recent price movements have started to look exponential, which reminds me of my mania template (as published in The shape of a bubble in May 2019). However, compared to previous gold bubbles , the recent movements have been tame. In the last 12 months, the price of gold has risen 22% (based on the recent peak of $2,430), while in the 12 months to end-August 2011 and end-September 1980, the gains were 46% and 68% respectively. The two-year gains in those episodes were 91% and 207%, respectively, versus 27% in this rally.

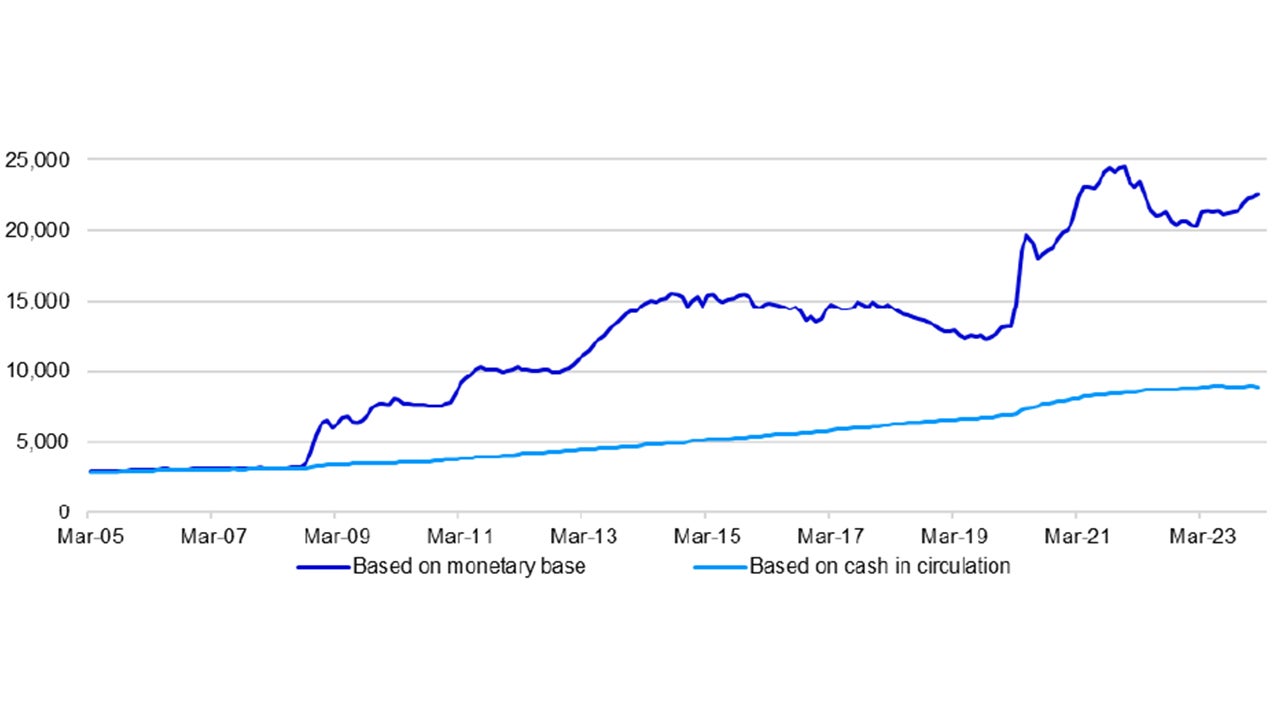

Talking of speculation, those looking for reasons to be bullish about gold, often fall back on the idea of a return to the gold standard. Figure 3 calculates the price of gold that would equalise the value of US gold reserves to either the value of cash in circulation ($8,907, as of February 2024) or the value of the monetary base ($22,500). When I first did this calculation in May 2020, the gold price needed to replace cash in circulation was $7,225 and I derived a similar estimate ($7,336) of the price required at the global level. Before getting too excited, it is worth remembering that a transition to such a system would likely involve the confiscation of private gold (there were restrictions on holdings of gold in the US between 1933 and 1974 and US Federal law allows for the confiscation of bullion).

Also, without wanting to spoil the party, though recent price gains are small compared to previous bubbles, it is worth bearing in mind that gold is now at a record high in real terms (see Figure 1). I suspect this will dampen demand for jewellery, technology and traditional investment purposes (which I think are price sensitive) and could even dissuade central bank purchases. I believe this may eventually cap the price.

In summary, the rise in gold over recent years is puzzling in the face of higher treasury yields and an appreciating dollar. Part of the explanation seems to have been central bank purchases but they have faded and speculation based on fears of geopolitical and/or economic instability appear to have taken over. When such buying happens it can become self-reinforcing and it is hard to know how far it can go but high prices could eventually dampen demand for other purposes.

Unless stated otherwise, all data as of 12 April 2024

Note: This is a theoretical simulation and there is no guarantee that these views will come to pass. Monthly data from March 2005 to February 2024. The chart shows the price of gold that would equate the value of official US gold reserves to the value of the monetary base and cash in circulation, respectively. Source: LSEG Datastream and Invesco Global Market Strategy Office