Uncommon truths: What would a Labour government mean for the UK?

UK elections will be on 4 July and a change of government seems likely. We doubt Labour’s proposals will shake financial markets but the long-term fiscal challenge is enormous, whoever wins.

Prime Minister Rishi Sunak has announced that the UK election will take place on Thursday 4 July and not in the Autumn, as most of us had expected.

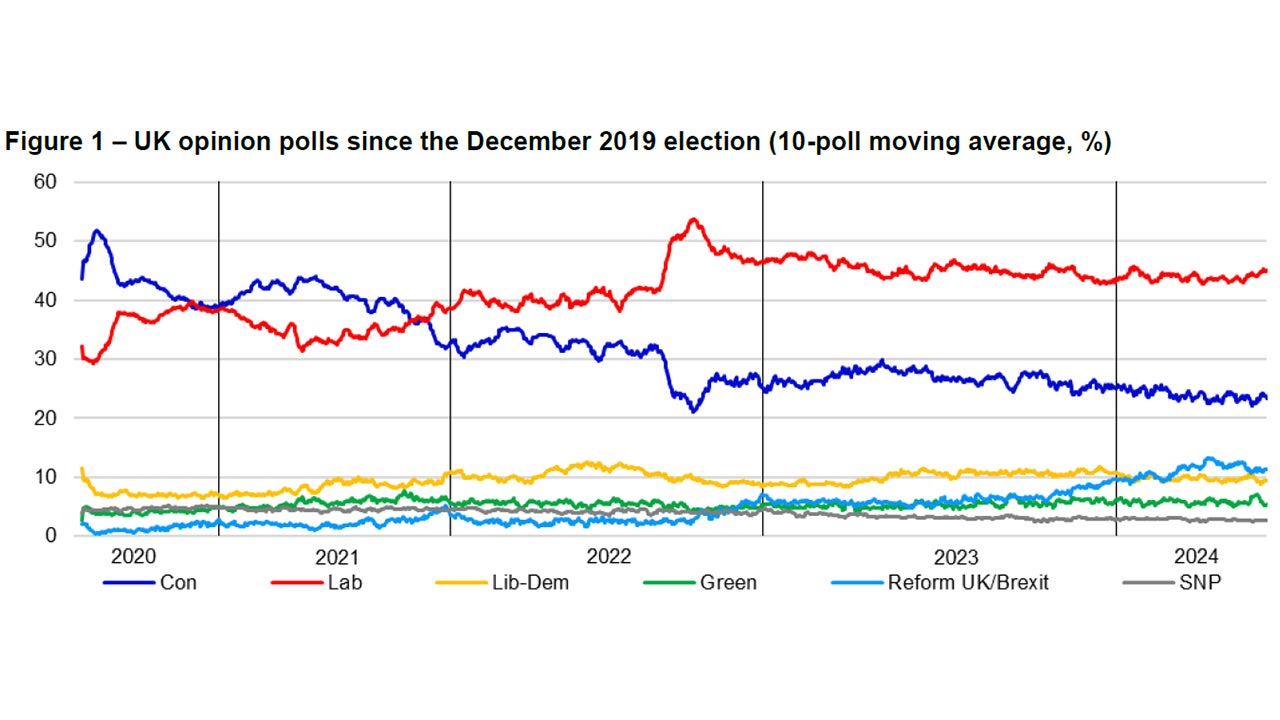

Whatever the reason for calling the election early, Figure 1 suggests it is a desperate roll of the dice by a prime minister perhaps about to suffer a large defeat. The gap between Labour and the ruling Conservatives has been hovering around 20 percentage points throughout 2024 (an amazing turnaround from the 11.5 percentage point lead enjoyed by the Conservatives at the 2019 election). Apart from a blip in 2021 (no doubt linked to the rollout of Covid vaccines), the Conservative share of vote has been trending down since that 2019 election, while that of Labour has been trending up (a trend accentuated by the ill-fated prime ministership of Liz Truss in September/October 2022).

Based on Figure 1, the only doubt seems to be the size of the Labour majority. Indeed, those surveys that have been translated into constituency by constituency outcomes (using large samples and a new technique called multilevel regression and poststratification) make difficult reading for the Conservatives. Of the four such surveys in 2024, the smallest majority predicted for Labour was 120 and the largest was 286. To put this into context, Boris Johnson won a majority of 80 in 2019, and the largest post-war majority was the 178 won by Labour’s Tony Blair in 1997.

So, why is Labour so popular? It isn’t to do with the popularity of its leader. Sir Keir Starmer has a negative net satisfaction rating of similar size to that of Ed Miliband in 2015. Rather, it seems to have more to do with dissatisfaction with the Conservative party after 14 years in government. The latest Ipsos survey (early May 2024) gave Rishi Sunak a net satisfaction rating of -55 versus -18 for Keir Starmer. With that degree of dissatisfaction with the incumbent, the election appears to be Labour’s to lose. However, once in power, those negative net satisfaction ratings suggest Keir Starmer may have limited room for error.

What should we expect from Labour? The Labour manifesto has not yet been published but we have some pointers. Above all, their election messaging appears to be focused upon “change” (of government) and “stability” (as opposed to recent “chaos”). Importantly, Keir Starmer and his Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer (Rachel Reeves) have been careful to stress fiscal responsibility, so we shouldn’t expect big tax cuts or increases in spending.

Indeed, Labour appears to be sticking to the government’s fiscal rule, that government debt should be falling (as a share of GDP) between the fourth and fifth years of the budget forecast. Given the current state of government finances, that is a real challenge. Either taxes go up (but tax revenues are already the highest since 1949, as a share of GDP), current spending falls (for which neither party has much appetite) or public investment falls.

Note: Based on opinion polls from 10 January 2020 to 25 May 2024 (the first data point shows the result of the last general election on 12 December 2019). The uneven spread of calendar years is due to the different number of opinion polls in each year. “Reform UK/Brexit” shows the opinion poll results for the Brexit Party until it was superseded by Reform UK. Source: BBC and Invesco Global Market Strategy Office.

The latter seems to be the favoured option for both parties, but Labour’s plans are less draconian. According to the Institute for Fiscal Studies (see Public investment: what you need to know, April 2024), current government plans suggest public sector net investment (PSNI) will fall from 2.5% of GDP in 2023/24 to 1.5% by 2029/30 (investment spending will be frozen in cash terms beyond 2024-25). Labour plans an additional £23.7bn of investment spending over the next parliament, which the IFS suggests will bring the PSNI-to-GDP ratio down to 1.7% in 2029/30.

Other changes in fiscal policy are likely to be marginal (in my opinion), with possibilities including the imposition of VAT on private school fees, potentially raising £1.6bn per year, according to the IFS, and earmarked for the funding of more public sector teachers. The plan to scrap the “non-dom” status (whereby UK residents could avoid paying UK taxes on income earned overseas) was effectively “stolen” by the Conservative government (to fund tax cuts, rather than Labour’s plan to spend more on the NHS), though Labour proposes a further tightening of the rules that they estimate could raise an extra £2.6bn during the next parliament. There is also the usual plan to reduce tax avoidance (planned to raise £5.1bn per year by the end of the next parliament), with funds earmarked for the NHS and primary school breakfast clubs.

Labour market reforms seem likely to include the outlawing of zero-hours contracts, ending “fire and rehire” and facilitating union representation in all workplaces. This may raise costs and reduce employment in some parts of the service sector. Among other regulatory changes planned by Labour is a promise to bulldoze planning regulations, thus enabling the building of 1.5 million new homes during the five years of the next parliament (just below the 1.66m homes completed in the 10 years to 2019-20).

In the realms of investment and industrial policy, Labour’s Green Prosperity Plan includes: “A proper windfall tax on oil and gas companies”, the creation of Great British Energy (a publicly owned company to invest in clean energy) and a National Wealth Fund (with £7.3bn of public capital, aiming to crowd-in three times that amount of private capital into priority net-zero sectors). There are also ambitions to help small businesses to “Start-Up, Scale-Up”, including a transformation of the British Business Bank and an improvement of the links between UK institutional investors and venture capital funds.

As much as anything else, UK businesses appear to want stability and consistency, especially after the uncertainties brought by Brexit and important reversals of policy in recent years (scaling back HS2 and retreating on green ambitions, for example). Labour is saying the right things, in particular about building a more constructive relationship with the EU.

In summary, I think Labour’s proposals may penalise the oil & gas sector and businesses that rely on loose labour laws (the gig economy, say). The benefits seem likely to go to those enabling the greening of the economy, housebuilders and those struggling to trade with the EU. But none of this is news.

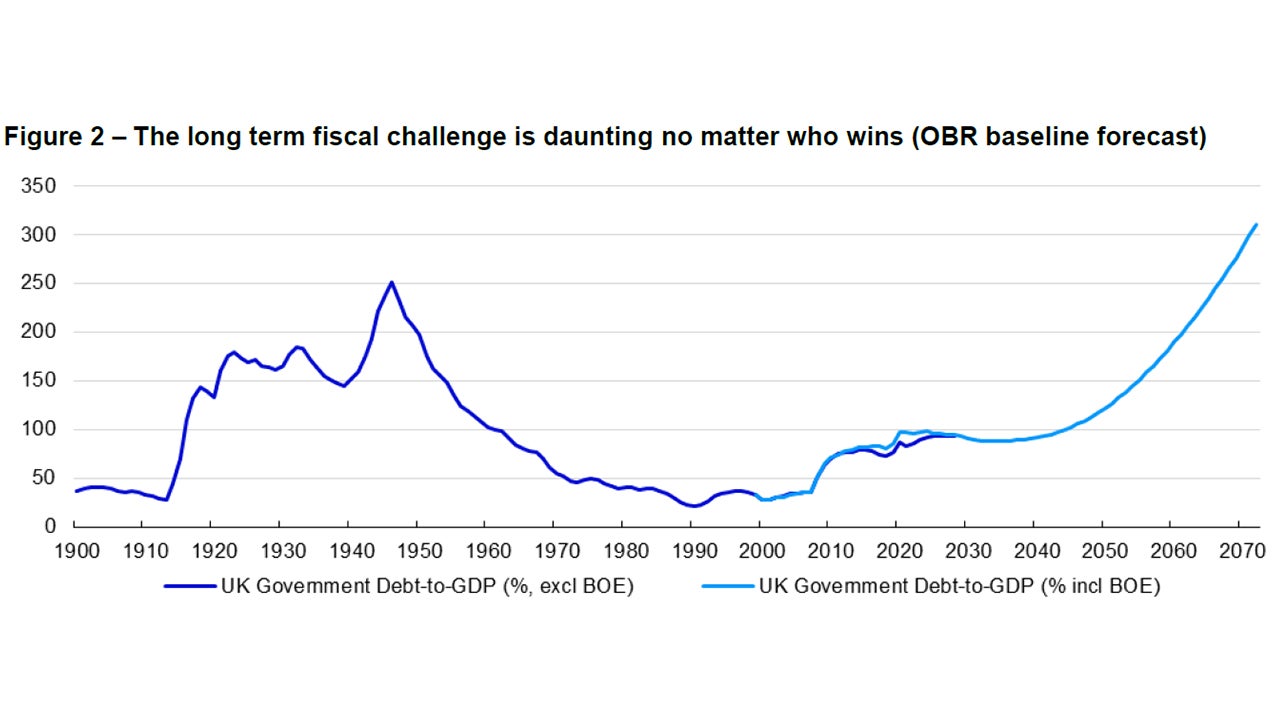

I think the macro impact will be small, though a change of government after 14 years may bring some optimism (as in 1997). Perhaps the biggest service the incoming government could provide would be to be honest about the state of government finances. Figure 2 shows the forecast from the Office for Budget Responsibility, which suggests that debt/GDP could rise from close to 100% to around 300% by 2070. Either productivity needs to be fostered (to boost growth) or taxes need to rise and/or the government needs to provide far fewer services (or consider default in some way). The true fiscal constraints are stifling (and not just in the UK).

Unless stated otherwise, all data as of 24 May 2024

Annual data for fiscal years from 1900-01 (labelled as 1900) to 2072-73. All data is provided by the UK’s Office for Budget Responsibility (using the baseline forecast). Data including the BOE (Bank of England) is from 1999-00 to 2072-73 and prior to 2029-30 is taken from Economic and fiscal outlook (March 2024), while data from 2029/30 is taken from Fiscal risks and sustainability (July 2023). Data excluding the BOE is from 1900-01 to 2028-29 and prior to 1999 is taken from Fiscal risks and sustainability (July 2023), while data from 1999 is taken from OBR economic and fiscal outlook (March 2004). Source: UK Office for Budget Responsibility and Invesco Global Market Strategy Office.