China real estate: Is China’s residential property boom over?

The census results from China’s National Bureau of Statistics released earlier this month confirmed a challenging reality for the country – its population growth is slowing, and quickly.

China’s population still grew over 5% between 2010 and 2020, but this figure was the lowest increase on record since the founding of the People’s Republic of China. Demographers and economists are focused heavily on how such a low birth rate and likely shrinking of the population will impact the domestic economy and broader society.

But this trend will have a more immediate impact on one of China’s most impressive growth segments since liberalizing its economy – the real estate market.

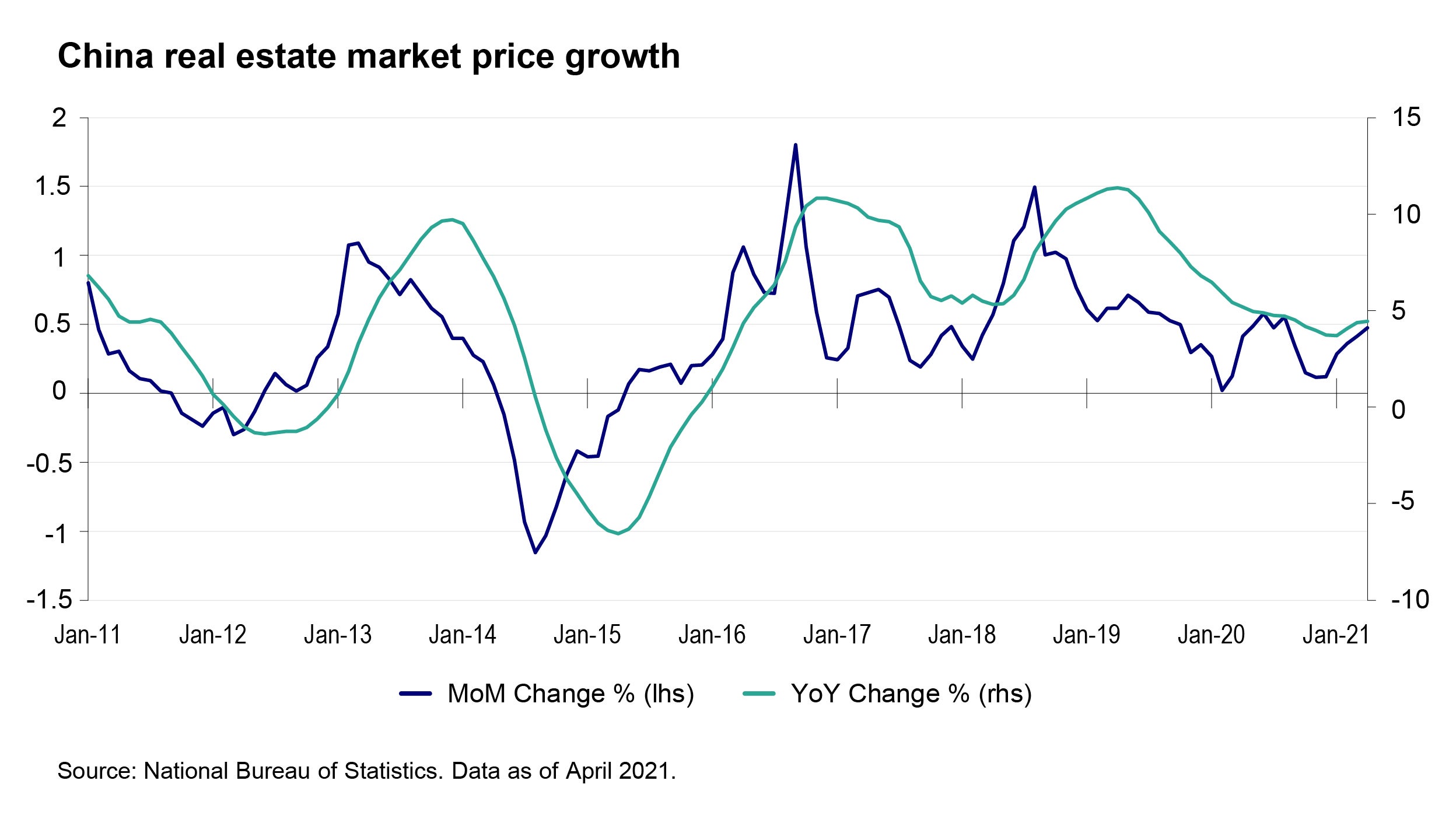

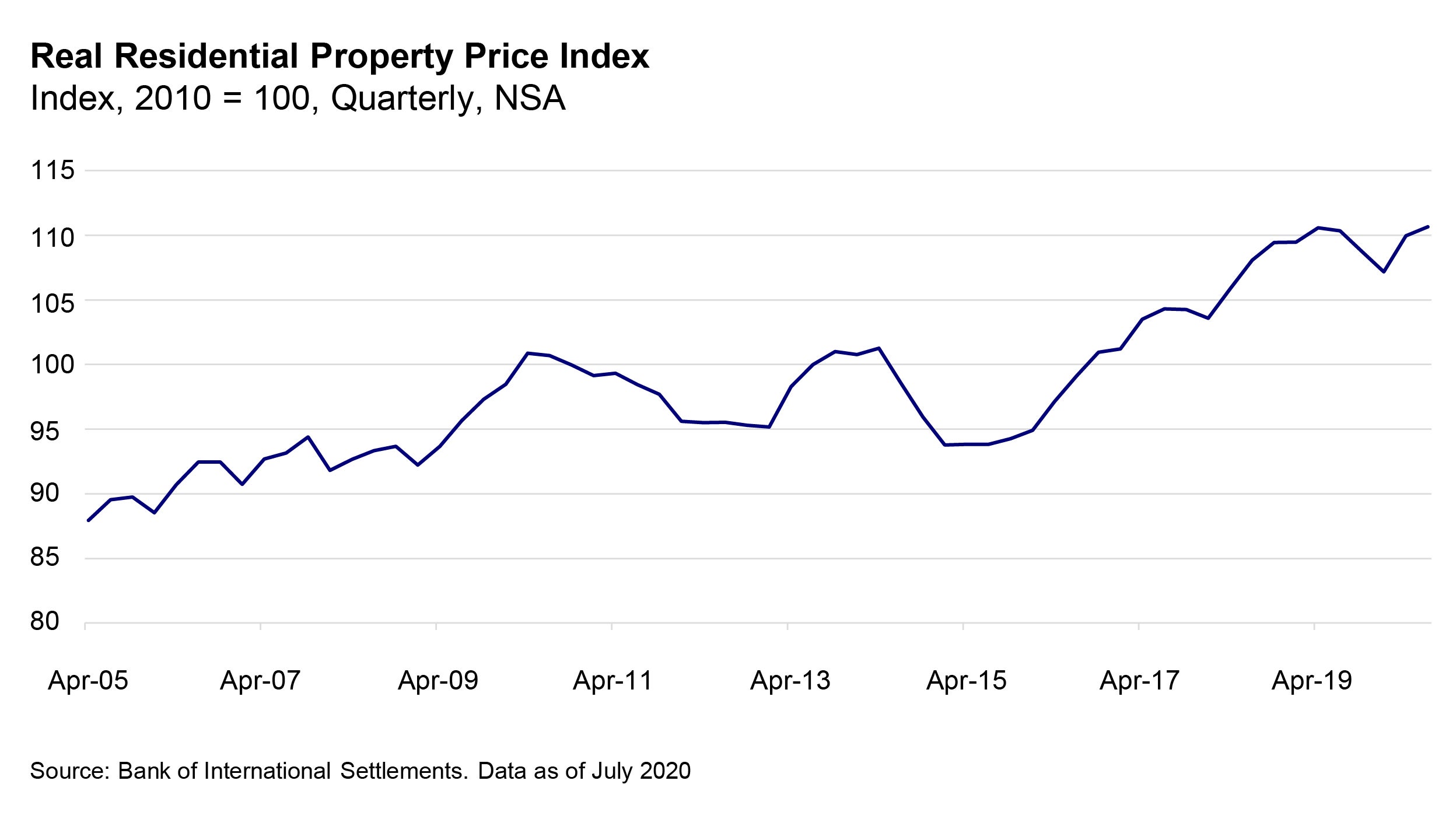

Property prices have grown dramatically, with home prices surging over 600% since 2010. Despite policy curbs, home prices grew at the fastest pace in eight months in April, with new home prices up about +0.5% month on month and sales up by about a third year over year.

Looking forward, supply-side policies to limit price growth are expected to continue to tighten, and demographic challenges will change the demand outlook. Taken together, it’s apparent that the residential market’s boom days are likely behind us – both in terms of prices increases and developers’ record profits.

The rise in property prices have been driven mainly by a growing middle class investing in real estate, with affluent households seeking yield and income on the one hand, and local governments relying on high prices to drive highly lucrative land sales to developers on the other.

Chinese policymakers are keen to avoid painful economic shocks, and the central government sees the property market as a major risk. President Xi Jinping declared in 2017 that “houses are for living in, not for speculation” – a principle that has guided authorities to deploy more stringent price-curbing measures.

China’s economic model means the government can take a relatively more active role in guiding market forces. With property in Tier One and now Tier Two cities becoming increasingly unaffordable, the central government has shown its willingness to act.

Over past years, the government has instituted land reforms and introduced new restrictions in property financing to better control the supply and demand components and prevent overheating.

From the supply side, land reforms re-classify state-owned land into commercial, industrial, and commercial purposes. According to the Ministry of Land and Resources, starting this year only around 14% of state-owned land will be allocated to residential construction, compared to the prior year’s 18%.

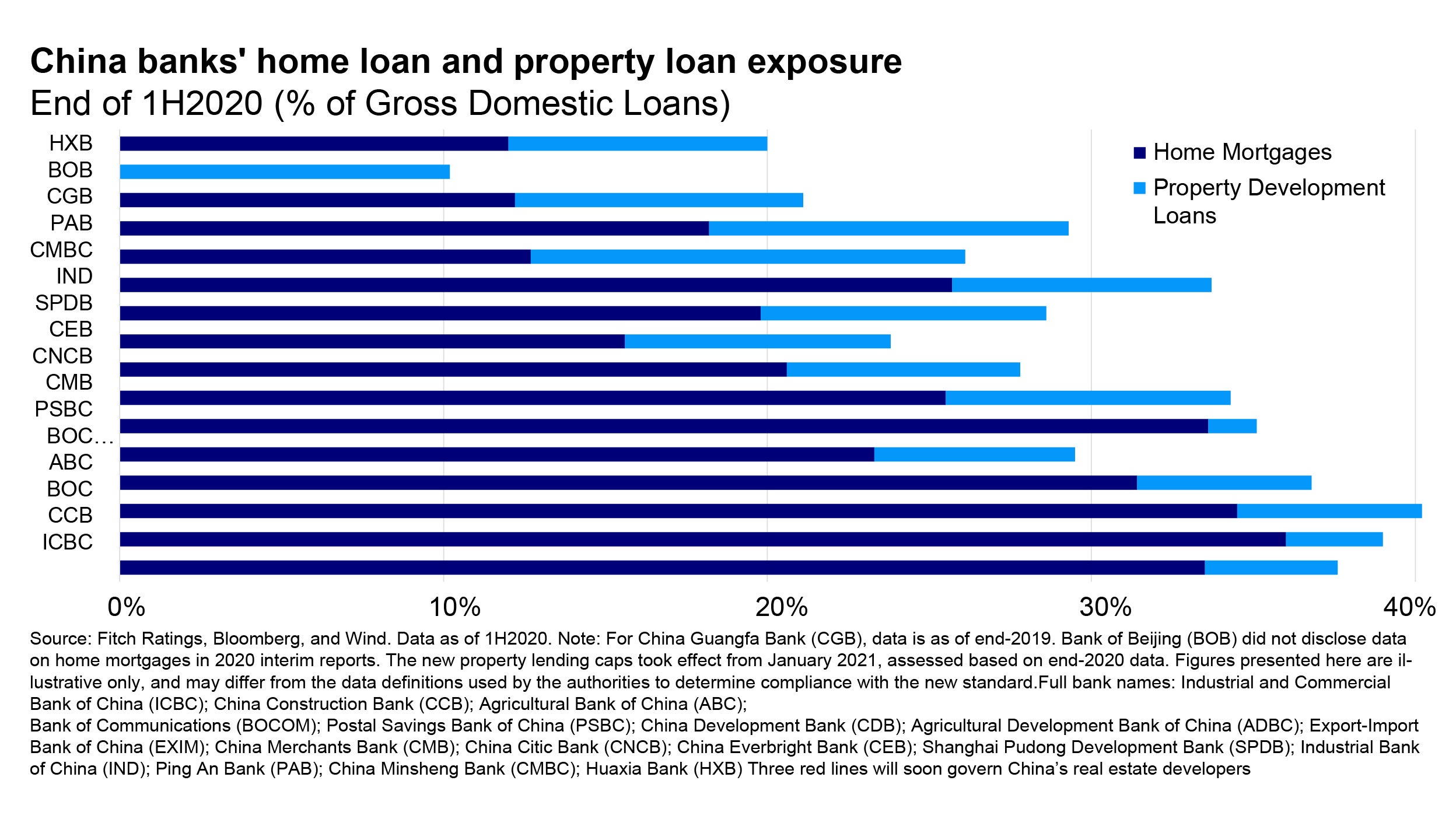

Easy liquidity for Chinese developers from state-owned banks has historically been a major driver of property prices, but last year the government deployed the “three red-lines” initiative to limit property development financing. This places a cap on the liability to asset ratio, which reduces net gearing and limits cash to short-term debt ratios. The PBoC also issued a regulation to cap property loans at 40% at China’s big four banks.

These supply side cooling policies have had some success in managing price growth, but it’s on the demand side where the more powerful economic forces take shape.

Along with a slowing population growth rate, the census data also revealed that first-hand housing sales peaked in 2017, due to the impact of the 2nd Child Policy. The declining trend of household formations – specifically the number of marriages per year – is also on the decline.

These are the most important drivers for the property market and represent longer term structural headwinds.

Already, the market is seeing vacancy rates on the rise in many major cities – for example Dalian, Harbin, Changchun and Shenyang have vacancy rates averaging around 22% – compared to the already high 15% in Shenzhen and 16% in Shanghai vacancy rates.

While upcoming Hukou reforms could drive further urbanization into Tier 1 and Tier 2 cities, this simply moves housing demand around internally without generating new demand. This could further inflate property prices and make housing unaffordable in big cities and worsening regional inequality.

Changes in access to investment products may also drive investors away from real estate as an asset class. Individual Chinese investors have historically had access to a limited range of bank-offered wealth management products; they also might have been badly burned investing directly in stocks during various cycles of market volatility since the 2008 Financial Crisis.

Increasingly though, investors are getting into the public markets through managed funds as well as passive ETFs – this might be a welcome diversification away from real estate speculation.

Policymakers need to walk a fine line. While ten years ago, the residential property market was supported by government policy and favorable demographics, the winds have now changed. China’s April real estate investment growth slowed to about 21% year over year, 4% lower than the prior three months.1 This slowdown could become a larger trend this year.

A version of this article appeared in South China Morning Post on 26 May 2021.

^1 China Jan-April property investment up 21.6% y/y, cooling from Q1, May 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/china/china-jan-april-property-investment-up-216-yy-cooling-q1-2021-05-17/