Uncommon truths: Can both equities and bonds be right?

It’s been a good start to the year, with positive returns on most assets. Upcoming Fed decisions may determine the immediate path of yields. But bonds are back and we think fund flows may push yields lower, to the benefit of equities and gold.

Equities are up and bond yields are down. As asked this week by erstwhile colleague Jay Pelosky (now at TPW Advisory): can both markets be right at the same time or will one be proven wrong? Meetings with investors over the last three weeks underline that confusion. The mood seemed to improve as the weeks passed (perhaps as markets rose) and, funnily enough, the closer we moved to the conflict in Ukraine. My year started in Lisbon and Madrid, where the mood was overall pessimistic, followed by further uncertainty in the Channel Isles. Investors in Dubai seemed to be still frozen in the headlights of 2022 but those in Bratislava, Vienna, Frankfurt and Munich seemed to be more optimistic.

Questions were frequently asked about the risk of recession, to which my stock answer is that I think it probable in Europe and possible in the US. Data released last week in the US was confusing: initial jobless claims suggest the labour market remains strong and PMIs for January showed some improvement (from low levels); new home sales remained low but were slightly better than expected and durable goods orders were down a bit; finally, the leading index for December was down 1.0% and weaker than expected.

Perhaps the most confusing of all was the GDP data for Q4. GDP grew 2.9% (annualised quarter-on-quarter), which was better than the expected 2.6%. However, more than half of that was due to an increase in inventories which added 1.5% to GDP, meaning that real final sales increased by only 1.4%, compared to 4.5% in the previous quarter. Consumer spending increased by 2.1%, broadly in line with the previous two quarters but with spending on goods increasing for the first time in four quarters, while spending on services seems to be decelerating (growth of 2.6%, versus 3.7% in Q3 and 4.6% in Q2).

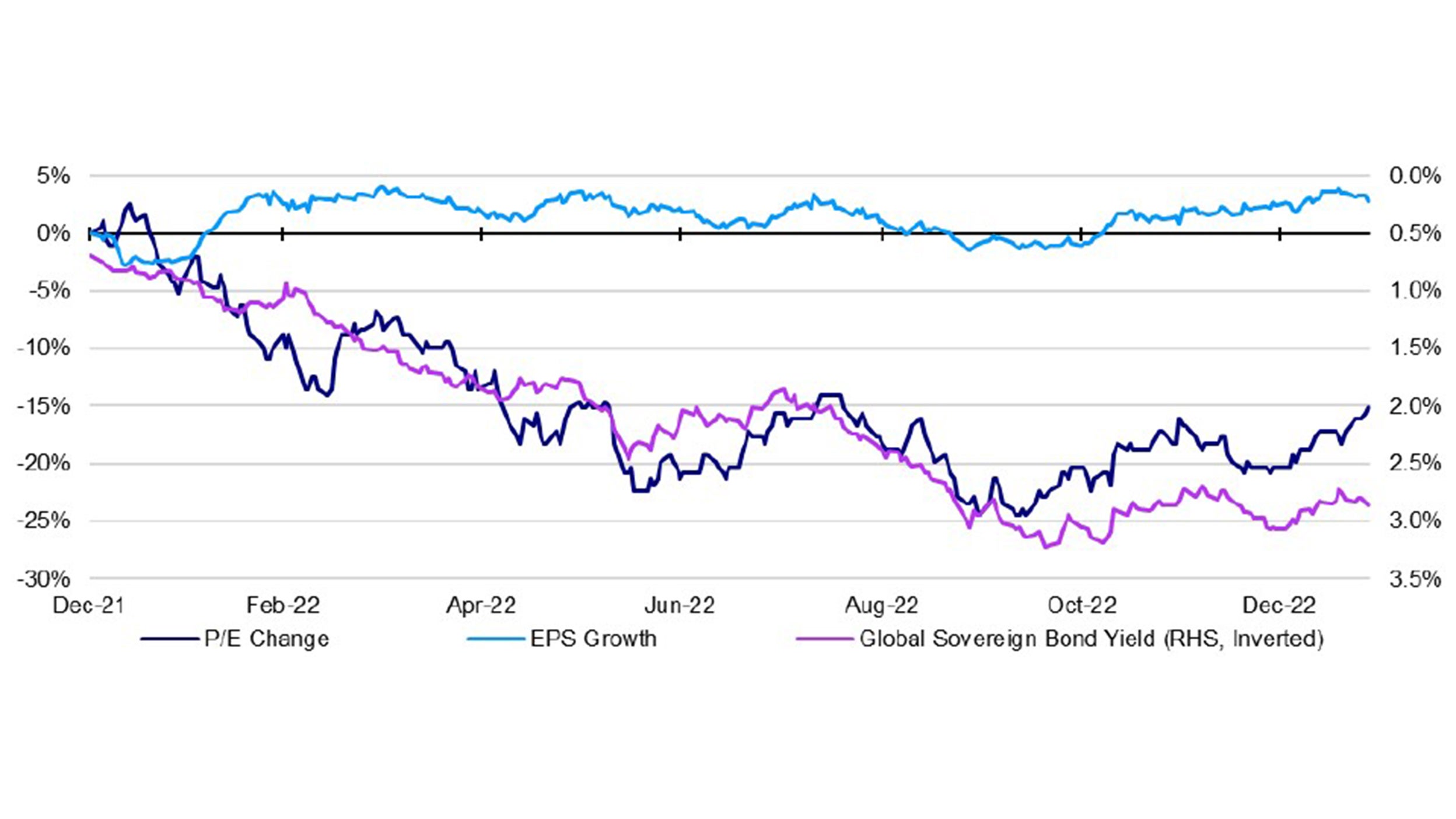

Worryingly, fixed investment spending shrank for the third quarter in a row (-6.7%). I say worryingly because investment is the component of GDP that often leads the economy into recession (in my opinion). Still, financial markets don’t seem overly concerned. Figure 1 shows that the historical P/E ratio on global equities has been expanding in recent months (based on the Datastream Total Market World Index). We suspect this is linked to the decline in bond yields, as suggested by Figure 1. Even better, profits have been creeping higher (until recent days), so that expanding multiples have been applied to higher earnings.

This wasn’t quite what we expected. When looking ahead to 2023, we predicted that both profits and long-term bond yields would fall (see The Big Picture - 2023 Outlook, published in November 2022). We also expected that the decline in bond yields would be enough to overcome the effect of falling profits, so that the equity asset class would generate small positive returns to the end of 2023. For example, our end-2023 forecasts envisaged that the US 10-year treasury yield would fall to 3.40% (currently 3.52%) and that the S&P 500 would climb to 4350 (currently 4071).

Notes: Past performance is no guarantee of future returns. Daily data from 31 December 2021 to 27 January 2023. Chart shows the cumulative change in price/earnings ratios and EPS (earnings per share) for the Datastream Total Market World index since 31 December 2021. Capital returns are the sum of earnings growth and the change in P/E ratios. The sovereign bond yield is represented by the yield-to-maturity of the ICE BofA Global Government Bond Index. All data shown in US dollar terms.

Source: Refinitiv Datastream and Invesco

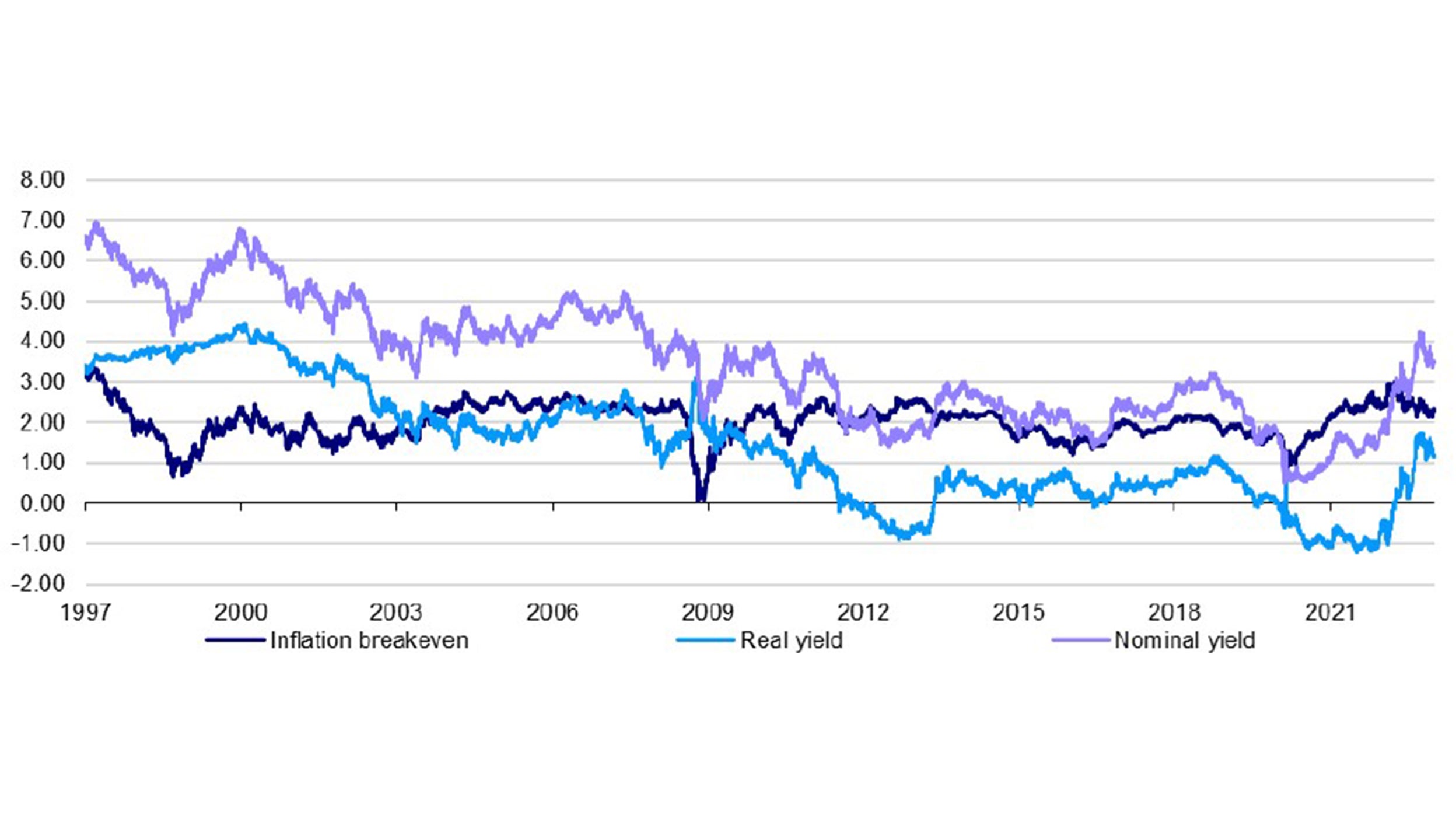

Since we published that 2023 Outlook, the US 10-year treasury yield has fallen from 3.84% to 3.52% (see Figure 2). Four-fifths of that decline came from a fall in the real (TIPS) yield (from 1.45% to 1.19%) and one-fifth from a reduction in the inflation breakeven (2.39% to 2.33%). That betrays not only confidence that inflation is heading back towards the Fed’s 2% target but also perhaps concern about the state of the economic cycle (hence the decline in the real yield).

Indeed, market expectations of the path of Fed policy rates are instructive. Bloomberg’s calculations based on Fed Funds Futures suggest the US central bank will raise rates by only 25 basis points at the meeting on Wednesday (1 February), followed by another 25 basis points at the next meeting (22 March). After that, however, the market is suggesting there will be no further rate hikes and that there will be two reductions by this time next year (with the first in November and the second in December or January).

That may seem dramatic but the market has been suggesting such an outcome since at least the start of the year and our 2023 projections were based on the same scenario. Our view was simply that US inflation would fall fast and that the US economy would weaken enough to push the Fed into easing.

The immediate direction of long-term treasury yields probably depends upon what the Fed does this week (in my opinion). I believe that no hike would see yields fall, that a 25bp hike would see little movement in yields after an initial rise and a 50bp hike would see yields rise. Thereafter, I suspect it depends on the strength of the economy. Continued deceleration could push 10-year yields down to 3.00% over the coming months, in my opinion, but a reacceleration in the economy could provoke a rebound in yields (perhaps back to 4.00%). One ray of hope may be that mortgage applications have risen in each of the first three weeks of the year, which could suggest the recent decline in mortgage rates is having an effect.

In any case, a common refrain among investors over recent weeks is that bonds are back! Even though I think bond yields will continue to rise over the medium to long term (as central banks reduce their holdings and real yields normalise upwards), I think cyclical forces could first take them lower. More strategically, real yields are higher than at any time since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), based on the evidence in Figure 2. Since mid-2022 I have felt that government bonds are at last worthy of consideration. The government bonds are currently accorded a Neutral weighting within our Model Asset Allocation, while investment grade (IG) and high yield (HY) credit are both Overweighted.

When it comes to the comparison with equities, dividend yield gaps (government bond yield minus equity dividend yield) suggest that government bonds are as attractive as at any time since 2010/11, in the US, UK and Eurozone. Anecdotal evidence suggests flows have recently been towards bonds and away from equities and not because of a fear of recession (see a Bloomberg article entitled “Pension funds in historic surplus eye $1 trillion of bond-buying”). Basically, the rise in bond yields is reducing the present value of pension fund liabilities, thus allowing them to de-risk, rather than chase returns.

Luckily, if bond yields do fall, I suspect it will be to the benefit of equities (and other assets such as gold). So, even though some equity market consolidation may occur over the coming weeks (Figure 1 shows that equity multiples have recently continued to rally despite a slight rise in bond yields), I suspect recent positive trends will then continue into 2023.

All data as of 27 January 2023, unless stated otherwise.

Note: Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Daily data from 29 January 1997 to 27 January 2023. “Real yield” is the 10-year TIPS yield.

Source: Refinitiv Datastream and Invesco