Uncommon truths: Seasonality, cyclicality and perfect storms

Volatility has returned, across a range of assets and geographies. This may be seasonal but I suspect there are also cyclical factors, which could be more problematic. This confluence of seasonal and cyclical problems comes when some assets are stretched, which is never a good time for the winds of change to arrive. I maintain a defensive stance within my Model Asset Allocation.

Wow, some weeks are more action packed than others but the past week will take some beating. Heightened tensions in the Middle East. Civil unrest in Venezuela and the UK (and the BOE easing for the first time this cycle). BOJ tightening, a sharply appreciating yen and a crumbling Japanese stock market (see Figure 3). Finally, the Fed’s indication that it may cut rates in September was outweighed by disappointing corporate results (especially in the tech sector) and signs of a weakening economy (bringing fears the Fed may have commited an error by waiting too long to ease).

The upshot was that equity prices fell in most places, despite the fall in bond yields fell (even in Japan). With the exception of Japan, though, the fall in equity markets during the week was not that dramatic (with the S&P 500 down 2.1%, for example). More concerning was the in-week volatility.

The problems started early in the week, with concerns about the outlook for semiconductor and mega cap stocks (with results awaited). The Fed then seemed to assuage fears by hinting of a rate cut in September (what happened to the idea of not easing so close to an election?). Despite the fact a September easing had been priced in for some time (according to Fed Fund Futures), bond yields fell and stocks rallied (with semiconductor stocks leading the way).

Bond yields continued to fall throughout the rest of the week: higher than expected jobless claims and weaker than expected ISM Manufacturing data on Thursday was followed by a disappointing employment report on Friday. The 10-year treasury yield closed the week at 3.79%, down 35 basis points (bps) in three days (and 90 bps lower than the 4.70% seen on 25 April). Despite the decline in bond yields, the previous stock market leaders led the way down as tech stocks failed to deliver the perfection that was built into their prices.

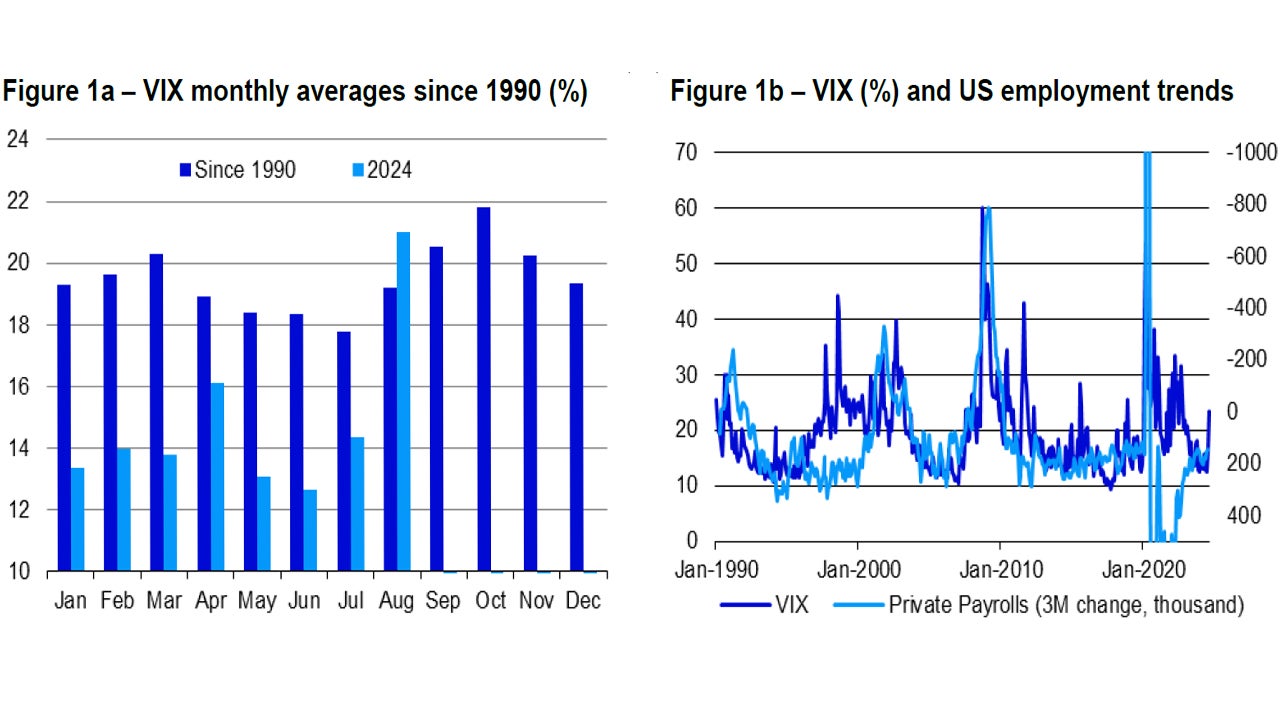

So, is this a temporary correction or something more sinister? On the optimistic side, markets tend to be thinner during the summer and volatility tends to pick up. Figure 1a shows monthly averages for the CBOE VIX index and there seems to be a seasonal pattern. Volatility tends to be lowest in the April-July period, but then picks up in August and carries on higher during September and October. Of course, these are averages over a number of decades and each year is different. Further, the August data for 2024 covers only two days. With those caveats in mind, the uptick in volatility in late July and early August 2024 fits with the historical pattern.

That could be reassuring, in that it suggests the uptick in volatility may be nothing more than seasonal and could therefore pass within a few months. However, those few months can still be painful (remember 1987?), especially with uncertainty about Fed policy and US elections in the background (along with rising geopolitical tensions in the Middle East).

Notes: Past performance is no guarantee of future results. The VIX index is designed to be a market estimate of the implied volatility of the S&P 500 Index, and is calculated by using the midpoint of real-time S&P 500 Index option bid/ask quotes (it is annualised implied volatility of a hypothetical S&P 500 stock option with 30 days to expiration). Figure 1a is based on daily data from 3 January 1990 to 2 August 2024. Figure 1b is based on monthly data from January 1990 to August 2024 (as of 2 Aust 2024)

Source: CBOE, Bloomberg, LSEG Datastream and Invesco Global Market Strategy Office.

What is more concerning is that as well as appearing to be seasonal, volatility also seems to have cyclical characteristics. Figure 1b suggests there is an inverse relationship between the US labour market and volatility. Though the labour market could not be described as recessionary, last week’s data confirmed that there has been a weakening. At the very least, I conclude that the ultra low volatility of recent months is no longer justified. At worst, if the economic deceleration continues (perhaps into recession), I would expect to see elevated volatility for some time.

The overlap of seasonal and cyclical factors may have exacerbated recent market volatility but I believe there is another factor at play: crowded trades and rich valuations. When assets become popular and expensive, they are vulnerable to sudden changes in the direction of the wind. Extreme concentration has driven broad US equity valuations to unsustainable levels (in my opinion). A market priced for better than perfection, with less than perfect outcomes, and indications of economic slowdown, have combined to bring sharp price movements in thin markets.

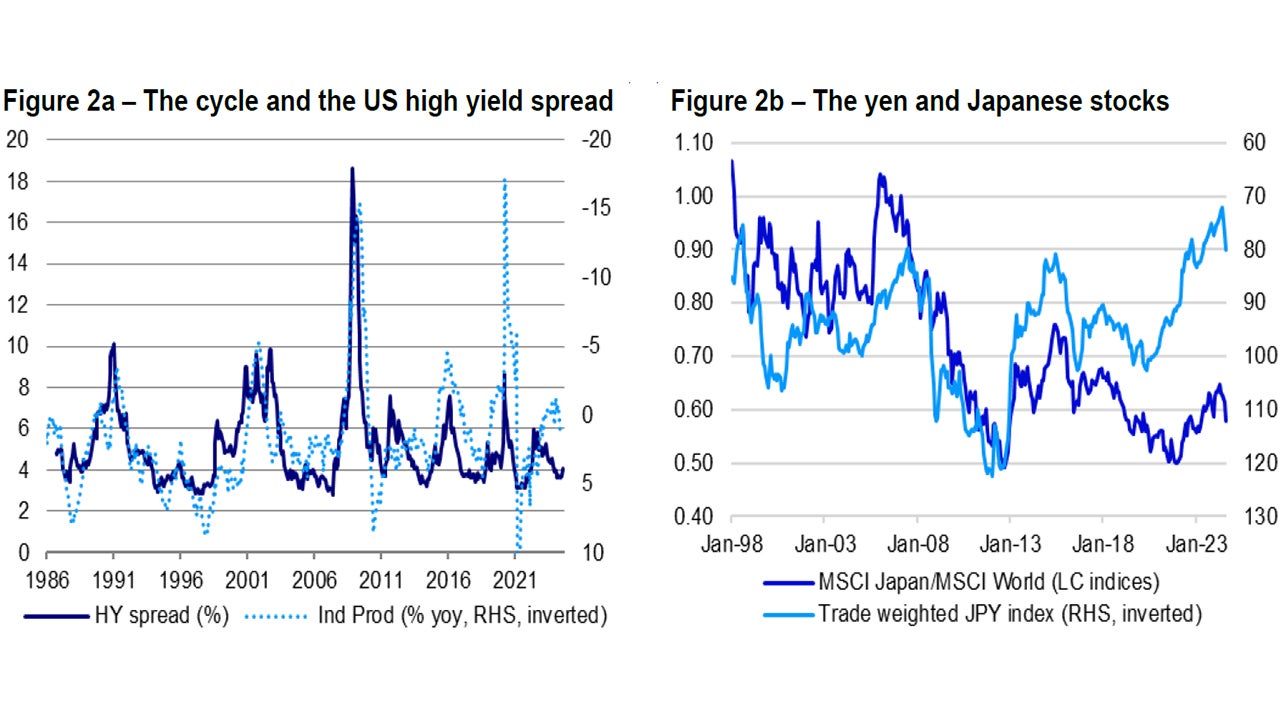

Of course, it is not just equity markets where valuations have been extended: US high yield spreads have been surprisingly tight, given the state of the economy (see Figure 2a). I recently reduced high yield to zero within my Model Asset Allocation (see Figure 5), in the belief that, with spreads so narrow, the return on high yield would struggle to exceed that on government bonds, especially if economic weakening raised default rates and caused spreads to widen (as appears to have happened).

The other market anomoly that I have highlighted for some time is the Japanese yen, which had fallen to extreme lows. The reason was obvious: the BOJ maintained a very accomodative stance, while most other central banks tightened aggressively over recent years. However, I was expecting the yen to recover once the BOJ started tightening and as other central banks started to ease. It may have taken longer than I expected, but, once it came, yen appreciation was swift. Having peaked at 162 on 10 July 2024, USDJPY yen had fallen to 146 by 2 August. I’m not a technical analyst but a glance at the chart suggests to me that 141 will be the next stop (which is where it was at the start of the year), and then 128.

Unlike many others with whom I have discussed the topic, I always believed yen appreciation would pose a threat to Japanese stocks (based on the evidence in Figure 2b). The 6% decline in major Japanese indices on Friday suggests the historical correlation is alive and kicking (Figure 5 shows that I am Underweight Japanese stocks and have been partially hedged from USD into JPY). Of course, such volatitly can impact other markets, especially considering that Japan is a net investor in the rest of the world: losses at home could provoke sales of overseas assets.

I would love to be able to conclude that recent volatility is nothing more than a bit of summer madness but the confluence of a range factors that have concerned me for some time (US economic deceleration and extended valuations across a range of assets), suggest that what appears to be seasonality may have more cyclical features behind it. I am happy to maintain tha cautious stance shown in Figure 5 until asset prices become more reasonable and/or economies improve.

Unless stated otherwise, all data as of 02 August 2024.

Notes: Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Figure 2a is based on monthly data from January 1986 to August 2024 (as of 2 August 2024). HY spread is the difference between the yield to maturity on the ICE BofA US High Yield Index and the US 10-year treasury yield. Figure 2b is based on monthly data from January 1998 to August 2024 (as of 02 August 2024). Trade weighted JPY index is calculated by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) but with own calculations for July and August 2024.

Source: BIS, MSCI, LSEG Datastream and Invesco Global Market Strategy Office

Investment risks:

Your capital is at risk. You may not get back the amount you invested.