Uncommon truths: The German tortoise and the US hare

Why has the German economy been struggling, while that of the US steams ahead? This was not always the case but since the start of the pandemic the US economy has performed on the back of rising government debt and falling savings rates. Will the tortoise have the last (and longest) laugh?

My return flight from Milan this week was cancelled due to the incoming aircraft having to land on one engine. Conversations with investors in Italy and elsewhere give the impression that the German economy is also flying on one engine, while the US continues at full throttle. Is this a fair representation of the facts and, if so, why the difference between the two economies?

GDP data support the notion that Germany is struggling (-0.2% year-on-year in 2023 Q4 and -0.1% for 2023 as a whole). Meanwhile, US GDP grew by 2.5% in the year to 2023 Q4 and 3.1% in 2023 versus 2022. No wonder the German 10-year government yield (2.40%) is 2% below that of the US (4.40%, as of 5 April 2024).

It may also help to explain why German stocks (+15.9% in 2023, according to MSCI) underperformed US stocks (+25.0%). However, a lot of that difference may have been due to the impact of AI enabling stocks on US indices, while the difference is less obvious so far this year (+7.5% for Germany versus +9.0% for the US, as of 5 April 2024).

Data released over the last week suggests the gap persists. For example, the US March employment report was again stronger than expected, with a 303k gain in non-farm payrolls (giving a monthly average of 276k in 2024 Q1, up from 212k in 2023 Q4). Also, the ISM Manufacturing survey improved in March to 50.3 (up from 47.8). Meanwhile, German factory orders were 10.6% below the year-ago level in February and the Manufacturing PMI fell to a lowly 41.9 in March.

However, other data muddies the water. The German Services PMI was reported to have improved to 50.1 in March (from a recent low of 47.7 in January), while the US ISM Services index fell to 51.4 (it was 53.4 in January). Also, US Wards vehicle sales data was weaker than expected in March (ask Elon Musk!).

Nevertheless, it is hard to argue with the general notion that the US is outperforming Germany, though this was not always the case. US real GDP growth may have massively outstripped that of Germany in the twenty years to 2019 (52.8% versus 31.0%), but there was virtually no difference on a per capita basis (29.1% versus 28.4%). Hence, over the long term, US economic strength versus Germany was largely a function of demographics (population growth over those two decades added around 0.9% to annualised US GDP growth but only 0.1% to that of Germany).

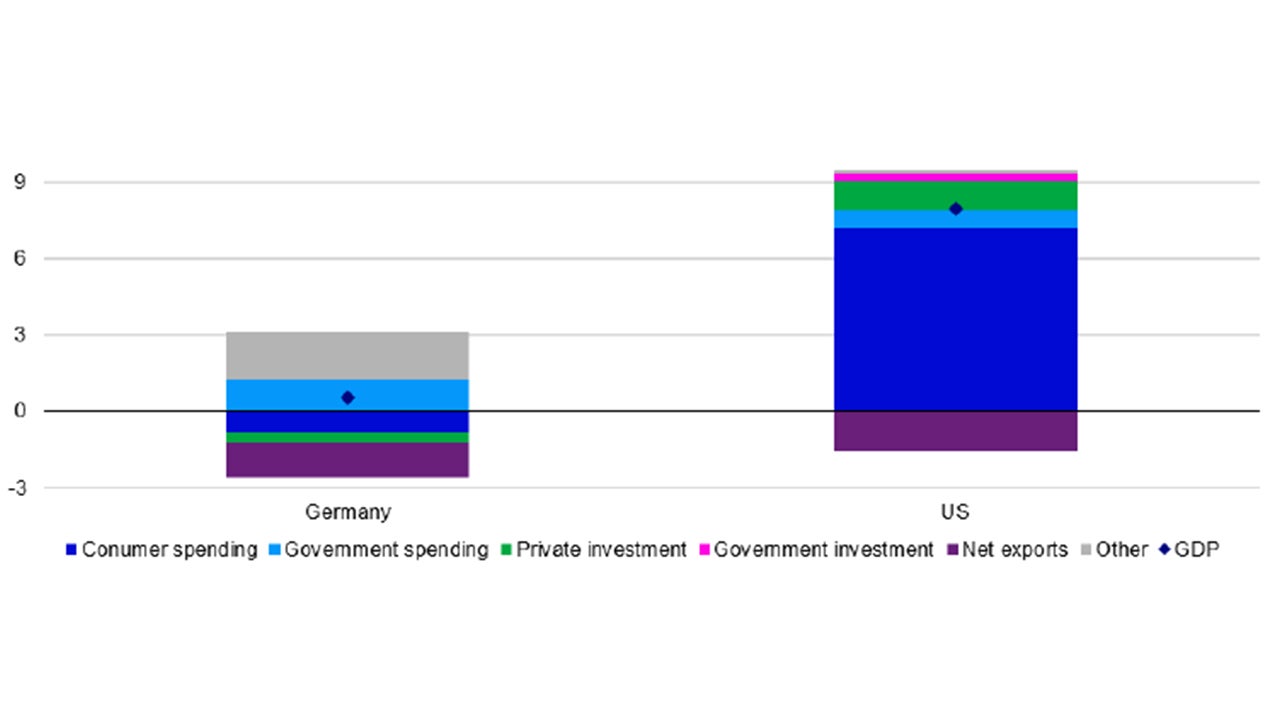

However, Figure 1 suggests there has been a dramatic change since 2019 (i.e. since just before the start of the pandemic). Over that period, German GDP grew by a measly 0.5% (0.1% annualised), while US GDP grew by 7.9% (1.9% annualised), all based on OECD estimates. On a per capita basis, German GDP fell by 0.8% (0.2% annualised), while US GDP grew by 6.5% (1.6% annualised). Germany has started to look like the tortoise to the US hare. Figure 1 suggests the big difference between the two countries was consumer spending. This detracted 0.8% from GDP in Germany, while adding 7.2% in the US. Indeed, the consumer contributed 91% of the GDP growth in the US since 2019, which is amazing giving that it only accounted for around 68% of GDP over that period.

Note: Based on annual data from 2019 to 2023. Based on OECD estimates of real spending in local currency terms. Investment items are based on gross fixed capital formation. “Consumer spending” is private final consumption expenditure, while “government spending” is government final consumption expenditure. “Other” is the residual between GDP growth and the growth provided by the GDP components shown in the chart (it includes inventory accumulation). Source: OECD, LSEG Datastream and Invesco Global Market Strategy Office

Other negative contributors in Germany were investment (private and public) and net exports. The latter was the only component to have made a negative contribution to the US economy. The fact that net exports made a negative contribution to both economies is curious but is corroborated by the common deterioration in current account balances. This seems easier to understand in the case of the US, given the strength of both its economy and currency.

It is less easy to explain for Germany. Perhaps the global shift to spending on services and away from goods has penalised an industrial economy such as Germany, as may have the lacklustre growth in China. Then again, the same could be said for Japan but it has seen no deterioration in its current account balance. However, other big European economies (France, Italy and UK) have all seen a worsening of their external balances, especially in 2022, which suggests a link to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine (higher energy costs in Europe and the loss of exports to Russia).

Coming back to consumer spending, what could explain the difference between the two countries in the period since 2019 (real consumer spending fell by 2.0% in Germany but increased by 6.7% in the US)? In one sense, the answer is simple: real net household disposable income fell by 0.8% in Germany (between 2019 and 2023) but increased by 6.5% in the US. Further, the household (and non-profit institutions) savings rate increased in Germany (from 10.8% to 11.7%), while falling in the US (from 7.6% to 4.4%). Not only did US household incomes grow more but an increasingly large portion of US incomes was spent.

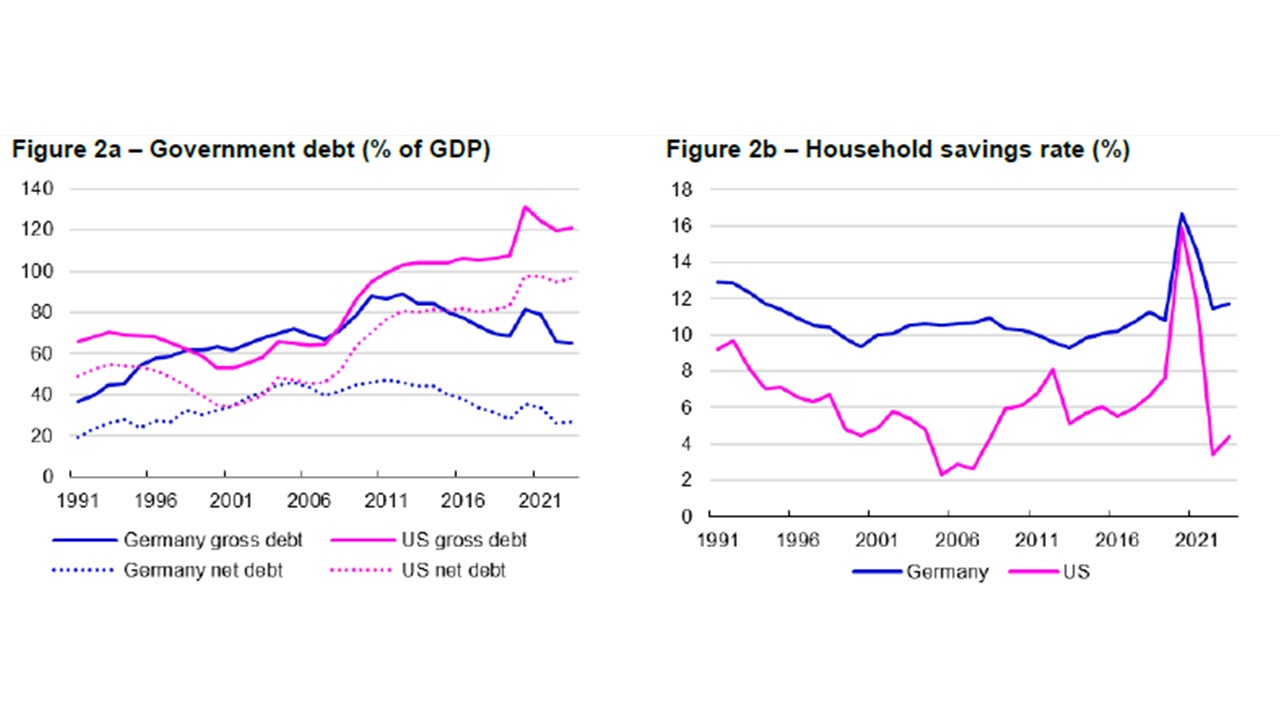

More difficult to explain are those divergences in household disposable income and in savings behaviour. I suspect it had something to do with differing government approaches to supporting economies. The German government did a good job of protecting household cash flows in 2020 (real household disposable income grew by 0.8%, similar to 2019) but that was reversed in 2021. However, the US government went much further, with tax rebates enabling an outsized 7.0% increase in real disposable incomes in 2020, followed by 3.3% in 2021 (in line with pre-2019 growth). Figure 2a suggests there was a bigger accumulation of government debt in the US at the time of the pandemic, with debt/GDP now higher than in 2019 (the reverse is true in Germany).

Savings rates naturally increased in both countries in 2020 due to the inability to spend during lockdown but the change was more noticeable in the US (the German household savings rate went from 10.8% in 2019 to 16.7% in the 2020, while that of the US went from 7.6% to 15.9%). The build-up of excess savings was thus greater in the US and their subsequent depletion helps explain why US consumer spending growth has been stronger in recent years.

Then, the final mystery is why the US savings rate has fallen so much. Figure 2b shows that the savings rate tends to be lower than in Germany but that gap is now wider than usual (the US savings rate is close to historical lows). This is perhaps linked to the feelgood factor that comes from US personal net worth reaching 761.2% of disposable income in 2023 Q4 (it had only ever been higher in 2021 and higher net worth is associated with lower savings rates). However, the same can largely be said for Germany (the net worth to disposable income ratio was around 900% in 2023 Q3).

In conclusion, the US has outperformed Germany to an unusual degree since 2019, largely on the back of government debt and falling savings rates. Neither the US government nor US households seem well positioned to spur future growth nor to deal with shocks. I think, the tortoise may have the last laugh.

Unless stated otherwise, all data as of 05 April 2024

Notes: Annual from 1991 to 2023 as estimated by the OECD. Figure 2a refers to general government financial liabilities. Figure 2b shows the net savings ratio of households and non-profit institutions. Source: OECD, LSEG Datastream and Invesco Global Market Strategy Office