ESG ETFs: Understanding the different approaches

We explore different approaches that ETFs with environmental, social and governance objectives can take, highlighting what they typically aim to achieve and how.

With contributions from Claudia Castro, Norbert Ling, Glen Yelton, James Matthews and Hamid Asseffar.

Investments in green, social and sustainability (GSS) bonds are enabling developing countries to undertake climate adaptation projects

The investment industry can play a pivotal role in mobilising institutional capital to scale up climate adaptation investments in developing countries

The European Union’s Green Deal Net Zero Industry Act (NZIA) is also expected to be a game changer for EU companies transitioning to net zero emissions

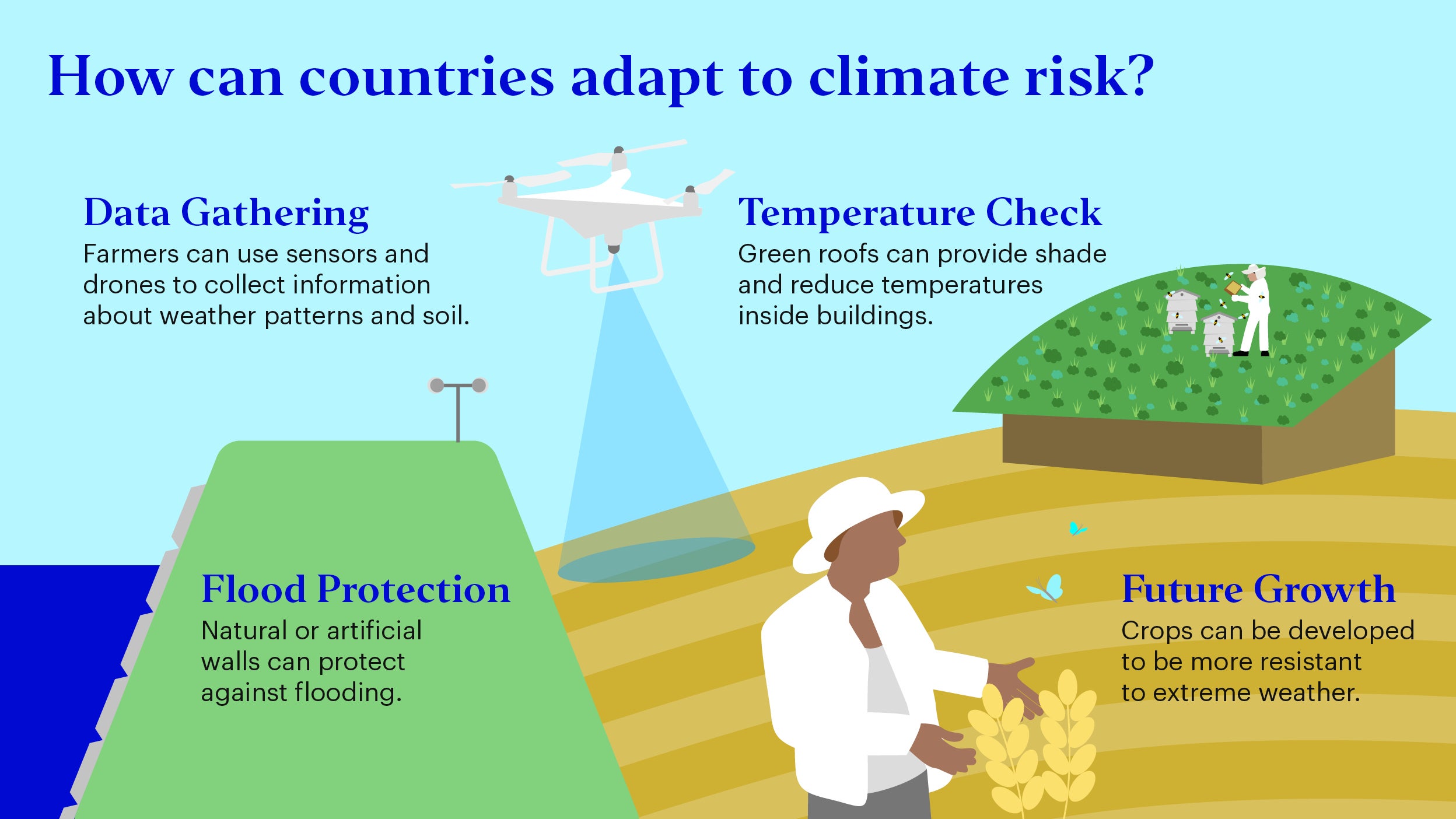

The Climate change risks is impacting our societies, disrupting our food security, infrastructure, water systems and coastal zones. Sea level rise, widespread wildfires and supply chain disruptions induced by harsher and more frequent severe weather events are only a few examples of these risks.

As a result, climate adaptation and climate transition have become two important investment themes in modern times.

Climate adaptation refers to actions taken by governments, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and companies to adjust and adapt to the current and future impact of climate risks. The goal of climate adaptation is to render communities and ecosystems more resilient to the detrimental effects of climate impacts. Climate transition, meanwhile, refers to the steps that organisations and governments are taking to reduce emissions and move towards a low-carbon economy.

Investing in resilience today helps mitigate future climate-related liabilities and costs, both direct (such as physical damage to assets) and indirect (such as higher insurance costs). Adaptation can therefore provide a triple dividend: it avoids economic losses, brings positive gains, and delivers additional social and environmental benefits.

Conservative estimates are that climate finance flows need to reach US$ 4.3 trillion annually by 2030 to transition to a more sustainable world this decade.1 Developing economies alone will require up to $300 billion a year by 2030 to adapt their agriculture, infrastructure, water supply and other parts of their economies to counterbalance the physical effects of climate impacts.2

But developing countries, which rely most on natural resources, often lack the financial firepower and institutional capacity to put adaptation programs in place to protect people and their livelihoods.

Climate adaptation efforts are as diverse as the effects the climate is making on societies. They include initiatives such as constructing sea walls to safeguard assets from flooding, developing early warning systems for weather events and developing drought-resistant crops.

Recent funding for developing countries’ climate adaptation efforts has largely been through the issuance of green, social and sustainability (GSS) bonds. Although the market for these bonds is still in its early stages, we believe that there is a lot of room for growth. As seen in Figure 2 below, the issuance of GSS bonds has grown rapidly as governments and businesses have ramped up their efforts to address climate impacts and meet net zero targets. Proceeds from these bonds are used to deliver positive environmental or social projects and help sovereign, corporate and financial institutions achieve their sustainable development goals (SDGs). Countries such as the Seychelles, Belize and Barbados have used innovative GSS bond approaches in “debt-for-nature” swaps. This is where a portion of a country’s foreign debt is cancelled in exchange for investing into, in this instance, marine conservation.

Source: Climate Bonds Initiative

Illustrating this, Egypt sold $750 million in green bonds to invest in areas like clean transport and renewable energy. In the Maldives, a $250 million “green adaptation bond” is being used to help cities adapt. Some projects have been employing innovative new approaches. Examples include funding small-scale water and sanitation solutions specifically developed for populations disproportionately impacted by climate risks, such as women and the poor.

A fund focused exclusively on addressing water and sanitation since its inception in 2021 has reached more than 942,000 people with safe water or sanitation. Nearly 175,000 microloans have been deployed to low-income consumers, which equates to more than $75 million in water and sanitation financing.[4]

So far, the broader public sector, including multilateral development banks (MDBs) and development finance institutions (DFIs), have played a major role in financing climate adaptation projects.

The IMF recently set up the Resilience and Sustainability Trust, its first ever long-term affordable financing facility, to support vulnerable countries tackling the challenges of climate disasters. However, a report by the Global Center for Adaptation (GCA) suggested “public spending alone cannot meet the adaptation finance gap, so private sector investment must scale alongside public investment to supplement limited public resources.”5 The GCA was set up in 2018 to support government and private sector financing for climate adaptation efforts.

The investment industry can offer institutional clients the opportunity to scale up climate adaptation investments in developing countries.

Multilaterals and supranational organisations are increasingly engaging with asset managers and other institutions to develop and issue climate bonds. The Asian Infrastructure Development Bank has just launched its first Climate Adaptation Bond. Investments will include water, urban development, transportation and energy.6

Challenges remain with GSS bond issuance being dominated by developed market issuers and skewed towards climate mitigation projects in the energy and transport sectors. These remain heavily funded compared to other adaptation projects.

To meet institutional standards and unlock private capital at scale, more origination and standardisation of information disclosure by issuers is required. Issuers in developing countries need more technical assistance to showcase how GSS debt instruments operate in practice, including guidance on how eligible adaptation projects are selected and evaluated, impact reporting and the role of external reviewers.

In developed economies, action towards climate impacts are more focused on mitigation or transitioning efforts to reduce or prevent greenhouse gas emissions. The effort in these countries has been on moving towards more renewable energy sources like solar and hydrogen, adoption of more sustainable food production practices and the implementation of technologies to mitigate greenhouse gases.

But getting to net zero is challenging and the trends have not been encouraging. According to Invesco’s Economic Transition Monitor, the CO2 intensity of economic activity needs to fall dramatically – far more than in recent decades – in order to achieve a global net zero economy.7 Recent research from environment disclosure firm CDP showed that among the 18,600 companies providing data, only 0.4%8 were assessed as having credible transition plans.

Nonetheless, policy initiatives and government regulations in Europe have set out goals for companies to follow. COP27 saw the launch of the Transition Plan Taskforce and Net Zero Guidelines to help guide companies and governments in establishing their transition plans.

The European Union’s Green Deal Net Zero Industry Act (NZIA) is also expected to be a game changer for EU companies transitioning to net zero emissions. This legislation fast tracks the development of net-zero technologies like renewable energy to help strengthen the EU’s move towards climate neutrality.

Companies investing in these types of technologies may be able to improve their top line growth rates by pulling forward future sales (recognising sales that would have occurred in future quarters in the current quarter). In our Pan European Small Cap Equity strategy we own petrochemical company, Technip Energies. The energy company offers innovative, carbon-free energy solutions in green hydrogen and offshore wind that help to grow, diversify and lengthen its order book.

The NZIA also requires at least 40% of clean energy equipment to be manufactured within Europe. This will accelerate demand for European-based manufacturers and suppliers like solar cell maker Meyer Burger. €375 billion in grants, tax credits, direct investments and loans from the NZIA will help to spur additional capital and operating expenditures, as well as tax support, to fund growth plans.

But the transition to a net zero global economy still faces significant challenges. Questions remain how to properly define “transition,” assess related progress and balance shorter-term financial implications.

There’s still a lot to be done in both climate adaptation and transition to address climate risks and ensure a resilient future. Further investment from large, long-term investors like pension schemes and insurers, could also help ensure positive change. If companies and governments are to meet their goals significant additional funds will be desperately needed.

Adaptation is the ability to change processes, practices and structures in response to actual or expected climate impacts and the ability to recover from climate-related risks. This could include building seawalls to protect coastal areas against floods, investing in green infrastructure such as improving road surfaces or planting heat resistant crops to deal with hotter temperatures or putting in early warning systems. By investing in resilience today institutions are mitigating future liabilities such as increased insurance premiums or risks to building systems or natural ecosystems.

Green, social and sustainability bonds are used to finance projects with environmental and socio-economic benefits. They can be used by companies or governments to meet their ESG targets. Investment in GSS bonds can help projects in food security such as agricultural technology and water irrigation or infrastructure like grid resiliency or reducing coastal risk. Other examples include waste management or water treatment and nature-based solutions such as reforestation projects.

The SDGs were established by the United Nations in 2015 to be a blueprint for peace and prosperity for people and the planet, now and into the future. There are 17 goals in total. They include no poverty; zero hunger; good health and well-being; quality education; gender equality; clean water and sanitation; affordable and clean energy; decent work and economic growth; industry, innovation and infrastructure; reduced inequalities; sustainable cities and communities; responsible consumption and production; climate action; life below water; life on land; peace, justice and strong institutions; partnerships for the goals.

The NZIA was set up to improve investment in the use of clean technologies in the EU. Changes have included simplifying the permit-granting process and reducing the administrative burden. The act sets out a framework to reduce the EU’s reliance on highly concentrated imports and increase the resilience of Europe’s clean energy supply chains. The legislation addresses technologies that will make a significant contribution to decarbonisation. These include wind turbines, heat pumps, solar panels, renewable hydrogen as well as CO2 storage.

The aim of the TPT is to develop the gold standard for private sector climate transition plans. Transition plans for organisations vary significantly making it difficult for stakeholders to assess their credibility. The TPT’s outputs will be drawn upon to strengthen future disclosure rules for listed companies and financial firms. The TPT is also working with international frameworks and countries that are developing disclosure guidance.

The Net Zero Guidelines is a tool for how policy makers and businesses can limit warming to 1.5 degrees and achieve net zero no later than 2050. The guiding principles and recommendations provide a common, global approach that companies and governments to achieve net zero greenhouse gas emissions through the alignment of voluntary initiatives and the adoption of standard, policies and national and international regulation.

Governments and companies are implementing climate transition plans to move to a low carbon economy. Plans are vital to show that organisations and governments are committed to limit warming to 1.5 degree. Plans should look at emissions that assets it owns or controls as well as indirect emissions such as the energy they use like buying electricity or cooling. They should also include emissions produced in the supply chain’s they use or the goods and services they buy.

ESG ETFs: Understanding the different approaches

We explore different approaches that ETFs with environmental, social and governance objectives can take, highlighting what they typically aim to achieve and how.

2022 Global TCFD Report

Our fourth annual TCFD Report provides a comparable, investor-relevant disclosure on our activities and capabilities in climate-aware investing. Find out more.

Invesco’s evolving fund range for sustainable investing – Article 8 and 9 funds

An Article 6, 8 and 9 fund classification help make investors aware about a fund’s sustainable characteristics. Learn more about Invesco’s Article 8 and 9 fund range.

1 Global Landscape of Climate Finance: A Decade of Data - CPI (climatepolicyinitiative.org)

2 How to Scale Up Private Climate Finance in Emerging Economies (imf.org)

3 Source: Climate Bond Initiative

4 Environmental Finance, 2022

5 GCA, Financial Innovation for Climate Adaptation in Africa, 2021)

6 AIIB Issues First Climate Adaptation Bond Targeting Resilient Infrastructure, 11 May, 2023

7 Economic Transition Monitor; Joint research with Tsinghua University on climate transition opportunities in APAC, etc.]

The value of investments and any income will fluctuate (this may partly be the result of exchange rate fluctuations) and investors may not get back the full amount invested.

This document is marketing material and is not intended as a recommendation to invest in any particular asset class, security or strategy. Regulatory requirements that require impartiality of investment/investment strategy recommendations are therefore not applicable nor are any prohibitions to trade before publication. The information provided is for illustrative purposes only, it should not be relied upon as recommendations to buy or sell securities.

Where individuals or the business have expressed opinions, they are based on current market conditions, they may differ from those of other investment professionals, they are subject to change without notice and are not to be construed as investment advice.