Henley Fixed Interest - 2020 outlook

Key takeaways

1.

2.

3.

The decision by central banks to ease monetary policy in 2019 helped bond markets to deliver strong returns. As a result, bond yields (which move inversely to prices and are a measure of the potential annualised return over the lifetime of the bond) across much of the market are now very low. Indeed, large parts of the government and corporate bond markets in Continental Europe and Japan now offer a negative yield - investing in these bonds and holding them until maturity guarantees you will lose money. What does 2020 have in store for bond investors? Will the rally continue, or are yields about to start rising?

Looking ahead, the more accommodative approach by central banks and ongoing demand for income should continue to support bond markets in 2020. However, with yields so low, a significant amount of easing is already priced in. It is therefore difficult to see a catalyst for yields falling much further. This, in our view, means capital gains are likely to be limited. Equally, in the current environment, there is very little in the economic data that points to a catalyst for yields to move significantly higher. These factors can change, but for now, our expectation is that 2020 will be a year in which bond returns are more modest and primarily derived from income.

The macro-economic picture

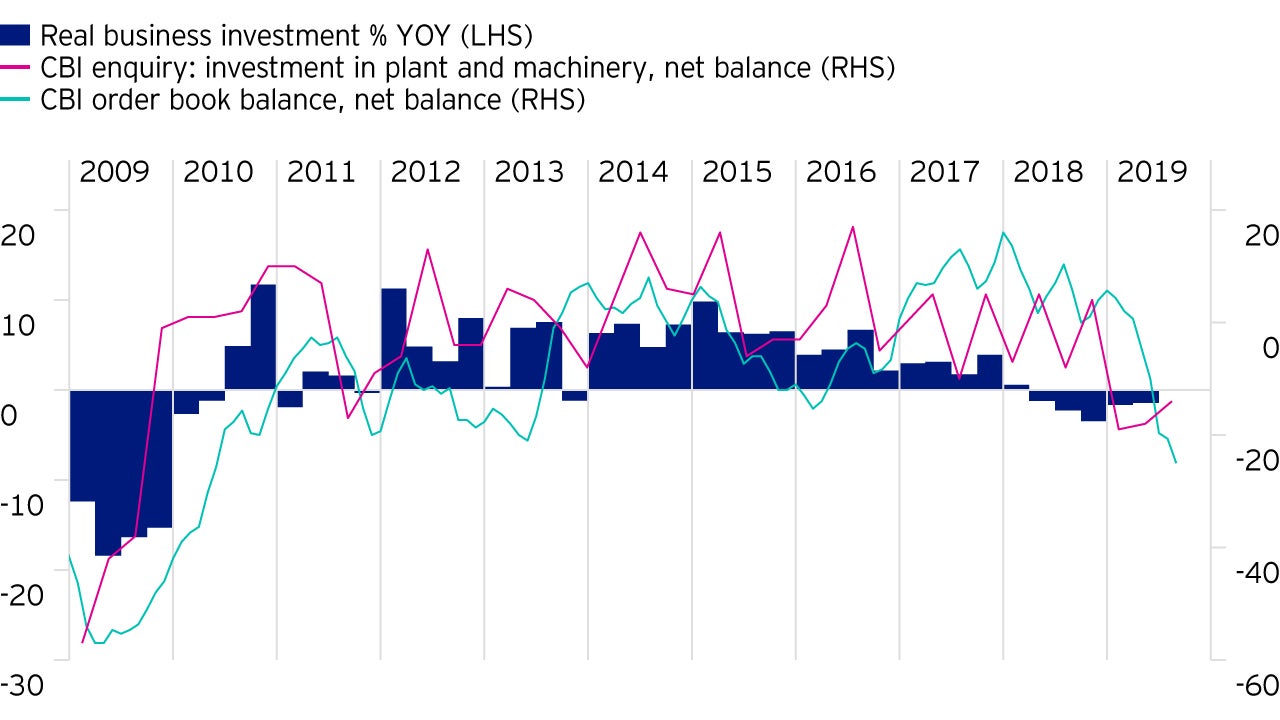

The latest data shows that global economic growth continues to slow amid a weakening of global trade. At the same time, inflation remains stable, but below the target level set by central banks. There is however some divergence between regions. For example, economic data continues to show the US to be on a firmer footing than the Eurozone.

There is a sense, particularly within the Eurozone, that we are now pushing on the metaphorical piece of string in terms of efficacy of monetary policy to stimulate growth. There have therefore been growing calls, underscored by the outgoing President of the European Central Bank, Mario Draghi, for more fiscal stimulus (more government spending). Politically, this is more challenging, and so while we think there could be an increase in government spending, which would normally be negative for bonds, this is unlikely to be on the scale we recently saw in the US.

In the US, the US Federal Reserve has signalled that it is approaching the end of its current period of cutting interest rates. However, the Fed has also made clear that the US economy is nowhere near the point at which it would be necessary to consider raising interest rates.

Where does this leave bonds?

Given the accommodative stance being taken by central banks, our baseline expectation is that short dated bonds will remain relatively anchored at current levels. However, the longer the tenure of a bond the more influenced it is by economic factors. There is therefore the chance that as economic data improves, we could see longer dated bond yields (bonds with 10+ years to maturity) rising. But, in the absence of inflation, and with central banks supressing yields through quantitative easing, any increase is likely to be met with significant demand. Any sell-off would therefore likely be contained. We have seen this cycle repeated since the Global Financial Crisis with US government bond 10-year yields peaking at between 2.5% and 3.5%.

Overall, corporate bond markets enjoyed a strong year with credit spreads (the premium over government bonds a company needs to pay to borrow) tightening. However, the strong performance was not universal. A number of issuers, particularly within the retail and auto sectors, came under significant pressure. This is not unusual, but this year it is perhaps more noticeable as it has been household names such as Debenhams, House of Fraser and Thomas Cook that have been making the headlines.

I don’t think that the weakness we have seen this year in these two sectors is symptomatic of a broader deterioration in credit quality. Indeed, default rates remain low by historical standards. It is worth reiterating that the volatility we have seen this year has at times created opportunities. By maintaining relatively high levels of liquidity in portfolios we have been able to exploit these. As we look ahead to 2020, we are well positioned to exploit any further such opportunities.

Looking at the broader picture, yields within corporate bond markets are now low, but overall continues to offer a reasonable amount of additional yield over government bonds. There are some pockets of value, particularly within the high yield market, the financial and telecoms sectors.

The risks

There are risks to this relatively benign view. Among the external factors that could negatively influence the market in 2020 are: the ongoing trade dispute between the US and China and its resolution or intensification; Brexit, and tension in the Middle East. Equally, an improvement in economic data perhaps coupled with some degree of fiscal stimulus in Europe could lead to longer dated yields rising, which in turn could lead to an increase in the premium over government bonds that companies need to pay to borrow. All of these factors have the potential to negatively affect bond prices.

What does this mean for funds?

Our direction of travel is to reduce credit risk whilst maintaining our low duration stance. But although we have been scaling back some risk, we have not been doing so aggressively as we are not too concerned about rapidly rising yields and we don’t want to give up too much yield. We are therefore maintaining a balanced approach. Relatively high levels of cash, government bonds and bonds maturing within 1-year are maintained in funds. This exposure is offset against higher yielding corporate bonds. This helps to mitigate periods market volatility while maintaining income and meaning that we are well placed to exploit any opportunities that do arise.

Related insights