Markets and Economy The four Trump policies most likely to impact economic growth

Deregulation and tax cuts could potentially provide a boost to US economic and market growth, while tariffs and immigration restrictions could pose challenges.

Based on market pricing of credit risk, last week’s emergent risks in the financial system have so far been concentrated in Credit Suisse.

Monetary and fiscal policymakers are 4 for 4 with decisive responses since problems began appearing last fall.

The U.S. Federal Reserve will meet this week and decide what to do with monetary policy in the wake of significant banking issues.

For those of you who have heard me present over the last several months, you may recall that one of the first slides in my deck comprises a simple quote:

“Central banks around the world have been raising interest rates this year with a degree of synchronicity not seen over the past five decades…”

This quote comes from a letter issued by the World Bank last September. It’s a recognition of how momentous 2022 was — especially how awful it was for most asset classes — but also a realization that some unintended consequences may come as a result of such aggressive, synchronized tightening.

And here we are. Last week saw a continuation of issues facing some U.S. banks. Then problems quickly cropped up in Europe with Credit Suisse. Not surprisingly, fears have risen that there are more shoes to drop, that we are seeing a major crisis begin to unfold.

I disagree, and I want to share key reasons to be cautious and constructive rather than outright negative.

A handful of banks have faced issues that seem very closely related to their specific business models.

But it is just a few banks that fall into both categories — banks with losses that also have a high percentage of assets that are not FDIC insured.

Credit spreads support the notion that the problems facing banks are fairly isolated. Based on market pricing of credit risk, last week’s emergent risks in the financial system have so far been concentrated in Credit Suisse. Indeed, over the past year, Credit Suisse has almost consistently featured the highest credit default swap spreads among the Financial Stability Board’s list of systemically important financial institutions. Broader measures of credit default swap spreads across the banks on this list suggest markets do not perceive other financial institutions as carrying similar risk, hence there is a low risk of contagion.1 Having said that, it does not mean that all has been fully resolved. We may see certain banks requiring a capital increase at some point to maintain ratios above regulatory limits.

If this was a systemic crisis, the European Central Bank (ECB) would not have hiked rates 50 basis points last week. By hiking rates 50 basis points, the ECB sent the message that it is business as usual.

It’s worth noting that late on Thursday, the U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed) revealed that $152.9 billion was borrowed from its discount window, which provides loans of up to 90 days, and another $11.9 billion was borrowed from its new credit facility, the Bank Term Funding Program, which provides loans up to one year. This is far above normal and is actually higher than the peak of discount window borrowing seen during the pandemic and the Global Financial Crisis.2 However, First Republic revealed that it had borrowed approximately $100 billion from the Fed. So just one bank accounted for the bulk of discount window emergency borrowing, supporting the emerging consensus that this is a specific not systemic run.3 It also appears that deposits leaving other mid-sized regional banks, like First Republic itself, are moving to larger banks rather than exiting the banking system as a whole, as would be the case in a run on banks across-the-board.

Monetary and fiscal policymakers are 4 for 4 with decisive responses since problems began appearing last fall.

The news of swift policy responses such as discount window borrowing may cause initial jitters for markets if it continues; however, this borrowing may actually instill confidence in markets, as it underscores the availability of powerful backstops.

More or less in line with the textbook — and the Bank of England response to the UK pension fund industry pressures — liquidity facilities like the Fed’s discount window and its new Bank Term Funding Program are being targeted at regional banks facing deposit withdrawals. Failing banks with unsustainable losses like Silicon Valley Bank or Signature Bank or challenged business models like Credit Suisse are being restructured or taken over.

Take the case of the UK pensions shock. The Bank of England (BoE) continued with rate hikes to control inflation and restore price stability as a complement to liquidity support and temporary bond-buying, targeted at the pension sector. While continuing to hike rates, it signaled slower hikes and possibly an earlier end to hikes. We see the ECB as in effect moving in the same direction and expect something similar from the Fed later this week (see below for more).

Further financial shocks may well come, but that does not mean systemic crisis. Monetary policy operates through financial conditions in markets, via banks, and indirectly even through private markets, many of which are linked to public markets via their funding and valuation metrics.

Financial volatility is, therefore, part and parcel of the policy tightening required to slow growth and inflation when they are too high and unemployment too low. Equally, financial stabilization through easing financial conditions and lower rates are how central banks revive growth, employment, and inflation in downturns.

We are all very focused on the risk of systemic financial crisis because of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis and the 2010-12 Eurozone Financial Crisis. But there have been plenty of financial crises that were regional or specific, and that came after Fed tightening yet were not systemic. In the European Union, banks have been gradually improving their balance sheets over the last decade, increasing capital and liquidity buffers, which should help tide them over.

As I mentioned last week, turmoil in the banking sector has helped ease yields very substantially. The yield on the 2-year U.S. Treasury note finished the week well below 4% (after hitting above 5% earlier in March) to 3.81%, and the 10-year finished at 3.39%.4 This is not just the U.S.; Germany’s 10-year yield fell to 2.09% after being at about 2.7% at the start of the month.5 This ongoing decline in bond yields helps take pressure off banks and other institutions facing these issues. All that said, the chance of financial shocks causing a recession are rising. We can’t ignore the potential for a significant pullback in credit. The risks of recession have clearly increased, although if a recession ensues it would likely be milder given strong labour market conditions.

Looking ahead, the Fed will be meeting this week, a very important one as they decide what to do with monetary policy in the wake of significant banking issues brought on by its aggressive rate hikes. The possible outcomes range from a 50 basis point rate hike to no rate hike at all, with most anticipating a 25 basis point rate hike (a few have even called for a 25-basis point cut).

I suspect that the Fed’s decision will be to raise rates 25 basis points. The ECB went ahead with a 50 basis point hike, and so to at least hike rates 25 basis points would be confirming this is not a crisis. However, I believe it would be overkill to hike rates 50 basis points, especially since financial conditions have already tightened in recent days.

One consideration for the Fed in making its decision is inflation expectations. We got good news last week in the form of the preliminary University of Michigan Survey of Consumers, showing that both one-year ahead and five-year ahead U.S. inflation expectations had fallen.6 This should help the Fed feel more comfortable about not hiking rates 50 basis points, which was considered likely until banking problems emerged several weeks ago. However, inflation remains high, wages have been rising and the labour market remains tight. A more modest 25 basis point hike would help the Fed balance the contrast between the strong labour market and the financial stress.

The Summary of Economic Projections and “dot plot” will be watched even more closely than usual, and it seems likely that some Federal Open Market Committee members may tone down their expectations for growth, employment, inflation, and the path of Fed rates, which should bring the expected path of policy closer to the market’s pivot view, but perhaps not all the way there.

Putting all this together, we believe that it still makes sense to be defensive in positioning in the short term, retaining capacity to extend exposures into longer-term, riskier, and less liquid assets when, and if, it becomes clearer that the financial stresses are being contained.

We also note that uncertainty tends to increase around financial shocks — another reason to be defensive and have “dry powder” to deploy as the outlook becomes clearer. Taking account of alternative scenarios can be a very useful tool for such periods.

The risk of an earlier and potentially deeper recession has increased on both sides of the Atlantic. There is also the risk that the issues in the banking sector are more widespread, although we believe that is unlikely. We will continue to monitor the high-frequency macro data, but will pay particular attention to indicators of financial stress or stabilization — including overall financial conditions, use of central bank loan facilities, pressure on short-term funding markets, and bank and financial equities particularly in leveraged institutions.

On the positive side, the risk of a debt ceiling crisis has likely decreased somewhat. The current banking problems underscore the need for the U.S. government to have the financial flexibility to provide support in the face of crises.

Another risk is that the Fed and/or ECB may slow down tightening too soon, and the path of inflation moderation going forward may not be satisfactory enough, forcing the resumption of a more aggressive and/or lengthier tightening cycle. A prolonged tightening cycle would increase pressure on the banking sector, increase recession risks, and prolong the time before an economic recovery could start.

With contributions from Arnab Das, Ashley Oerth, and Andras Vig

Sources: Bloomberg, Invesco, and Financial Stability Board, as of March 16, 2023. CDS (credit default swap) instruments are 1-year maturity for a selection of institutions. Some institutions were excluded due to data availability. Survivorship bias is likely as the list of institutions was obtained on March 16 and does not reflect historical compositions.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Governors, March 16, 2023

Source: First Republic Bank, “Reinforcing Confidence in First Republic Bank”

Source: Bloomberg, L.P., as of March 17, 2023

Source: Bloomberg, L.P., as of March 17, 2023

Source: University of Michigan Survey of Consumers (preliminary), March 17, 2023

Deregulation and tax cuts could potentially provide a boost to US economic and market growth, while tariffs and immigration restrictions could pose challenges.

The potential for significant deregulation and tax cuts has excited many investors, leading US stocks to “climb the wall of worry” despite immigration and tariff risks.

We expect significant monetary policy easing to push global growth higher in 2025, fostering an attractive environment for risk assets as central banks achieve a “soft landing.”

NA2802980

Important information

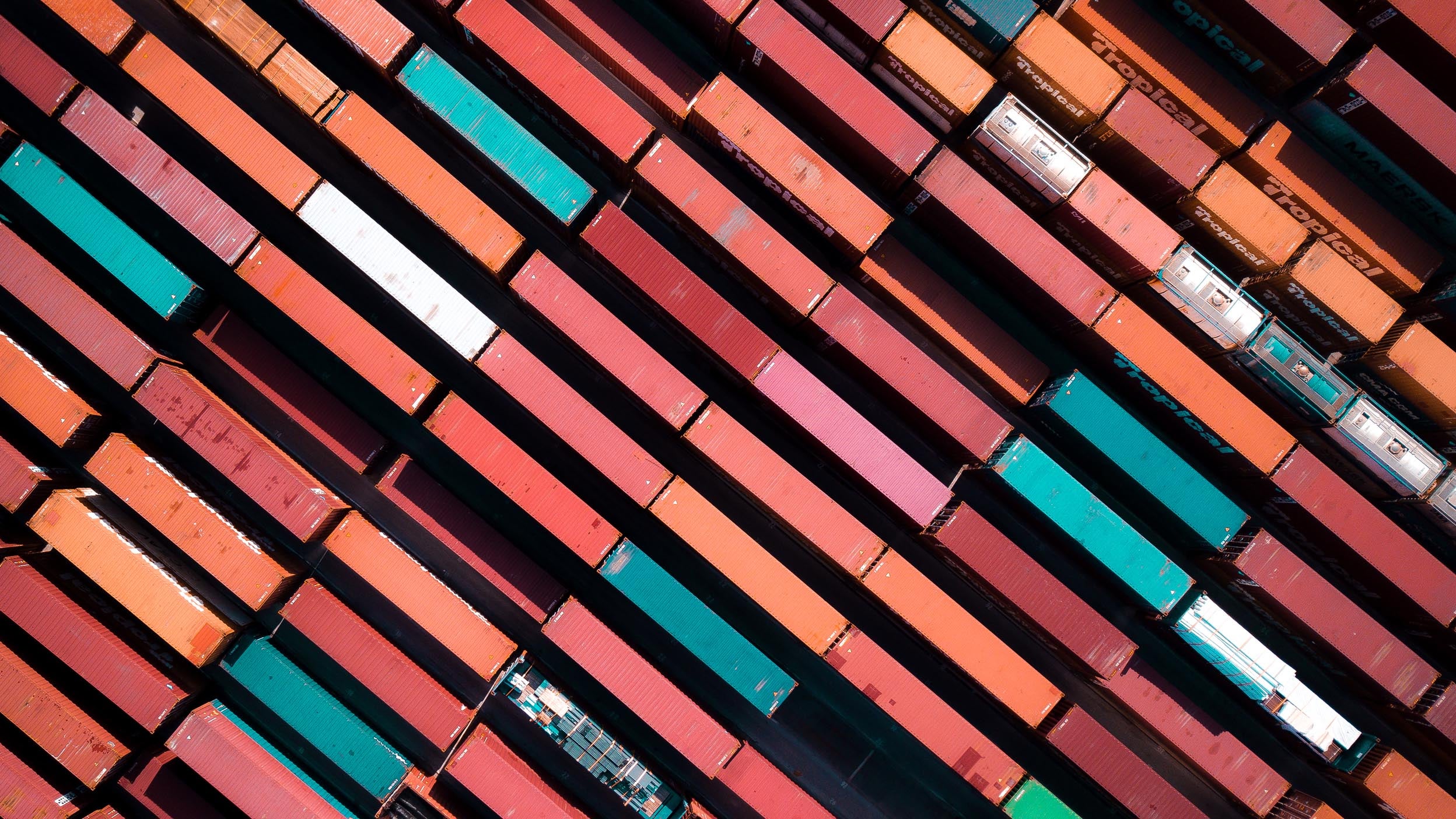

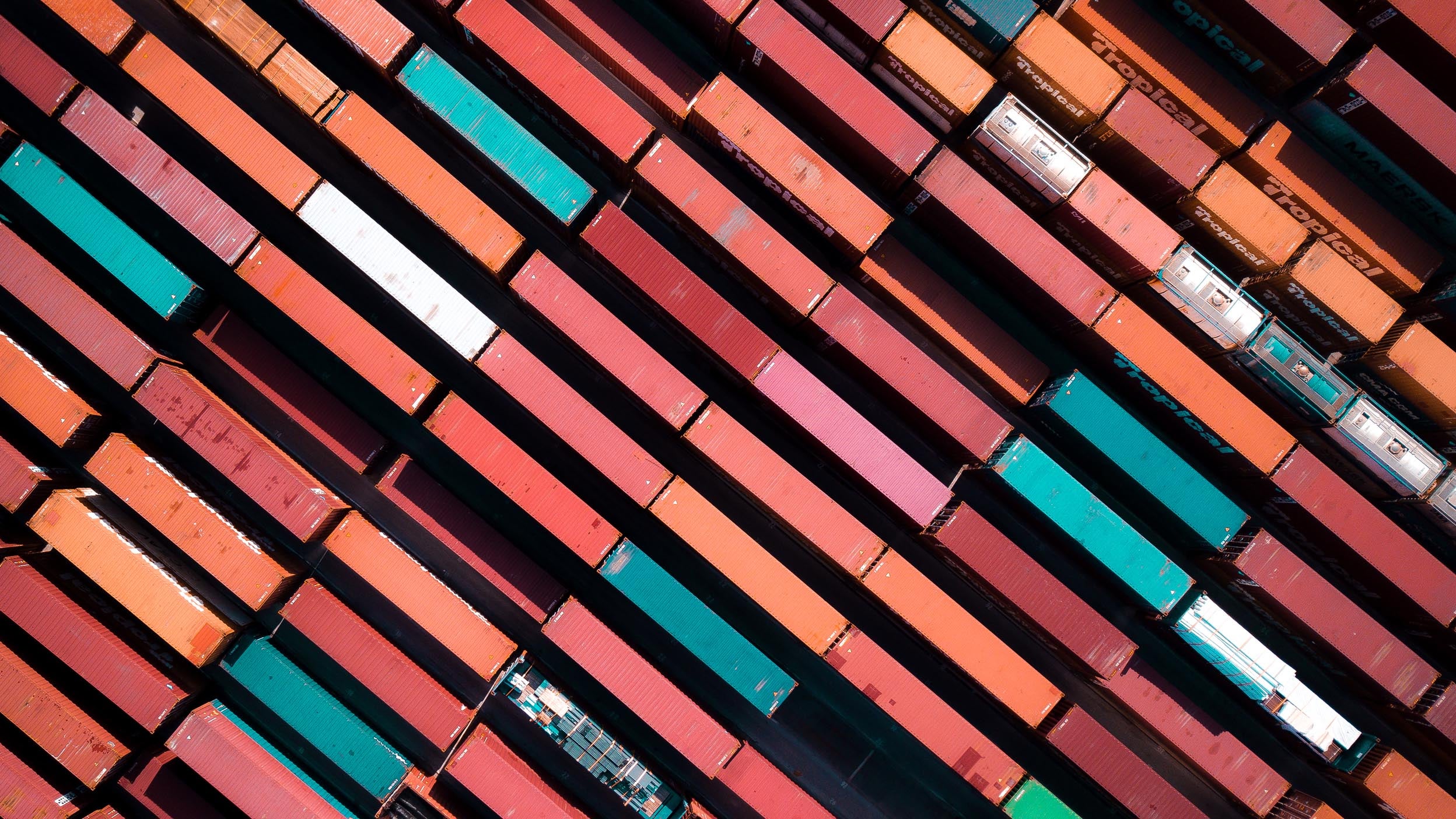

Header image: troischats / Getty

Some references are U.S. centric and may not apply to Canada.

All figures are in U.S. dollars.

Past performance is not a guarantee of future results.

This does not constitute a recommendation of any investment strategy or product for a particular investor. Investors should consult a financial professional before making any investment decisions.

All investing involves risk, including the risk of loss.

Tightening is a monetary policy used by central banks to normalize balance sheets.

A basis point is one hundredth of a percentage point.

Contagion is the likelihood that significant economic changes in one country will spread to other countries.

Credit spread is the difference in yield between bonds of similar maturity but with different credit quality.

A credit default swap (CDS) is a financial derivative that allows an investor to offset, or swap, their credit risk with that of another investor.

AT1 debt securities form part of the capital that banks issue to meet their regulatory requirements. They are designed to have loss absorbing features to provide a buffer against bank failure.

The Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP) was created by the Federal Reserve to make additional funding available to eligible depository institutions to help assure banks have the ability to meet the needs of all their depositors.

UK gilts are bonds issued by the British government.

The Survey of Consumers is a monthly telephone survey conducted by the University of Michigan that provides indexes of consumer sentiment and inflation expectations.

The Federal Reserve’s “dot plot” is a chart that the central bank uses to illustrate its outlook for the path of interest rates.

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) is a 12-member committee of the Federal Reserve Board that meets regularly to set monetary policy, including the interest rates that are charged to banks.

The Summary of Economic Projections is the economic projections collected from each member of the Board of Governors and each Federal Reserve Bank president four times a year, in connection with the Federal Open Market Committee's (FOMC's) meetings in March, June, September, and December. The charts and tables associated with those projections are released shortly following the end of an FOMC meeting.

The opinions referenced above are those of the author as of March 20, 2023. These comments should not be construed as recommendations, but as an illustration of broader themes. Forward-looking statements are not guarantees of future results. They involve risks, uncertainties and assumptions; there can be no assurance that actual results will not differ materially from expectations.

This link takes you to a site not affiliated with Invesco. The site is for informational purposes only. Invesco does not guarantee nor take any responsibility for any of the content.