The additional cost is widely accepted to be too large for the industry to absorb. To adapt, shippers can invest in fuel cleaning systems (scrubbers) to reduce reliance on low-sulphur fuel and they can also attempt to pass the cost to customers. Both approaches carry uncertainty.

Scrubbers trap sulphur, allowing ships to burn high-sulphur fuel without breaching emissions limits. The decision to install these systems has several factors. There are two upfront costs – buying / fitting the equipment and the loss of revenue while the ship is out of service. Analysing Maersk, JP Morgan estimate this at $5m per ship2. The savings side depends on the price spread. This can be affected by regional supply issues as well as the global market. The same analysis suggests that for Maersk a scrubber pays for itself in less than 18 months.

In recent quarters a number of shippers have decided that scrubbers are a good deal. The percentage of the container ship fleet fitted with them rose from 1% to 9% in 2019 and is predicted to rise much higher in 20203.

In the short-term, the evolution of the fuel spread will say whether this was the right call. But there is also regulatory and operational risk. Some cleaning systems produce sulphuric acid which is discarded in the ocean. This is permitted under the IMO regulations now, but it is quite imaginable that will change. China, Hong Kong, Singapore and some Caribbean islands have already banned this practice and there is pressure for global action4. Delays in fitting scrubbers can also lead to unexpected revenue loss and operational disruption.

Companies’ ability to pass on the cost is also unclear. Maersk has included a fuel cost adjustment factor in its longer-term contracts5. Companies can also negotiate longer-term fuel supply agreements. But neither of these measures address all the risk. Fuel adjustment features have often broken down in the past. This is especially likely if there is a dip in demand. Shipping is a competitive industry.

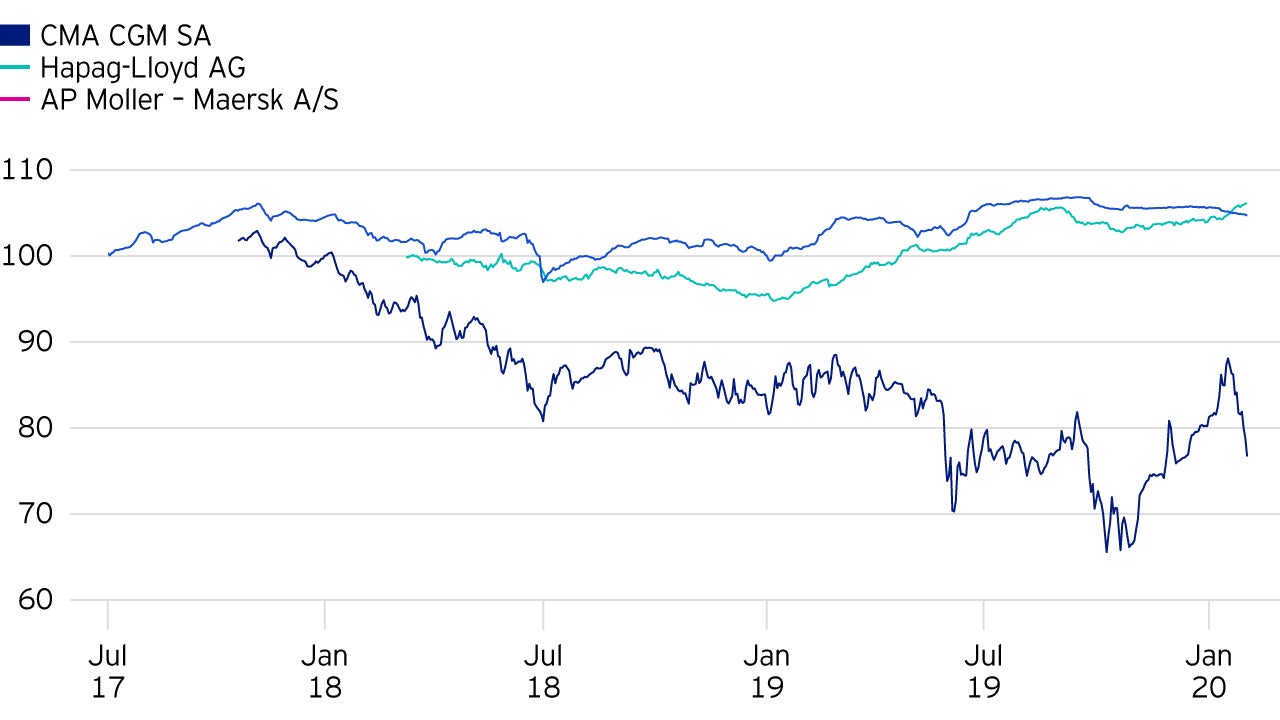

In our view, the larger players, such as Maersk and Hapag-Lloyd are likely to cope relatively well with the impact of IMO 2020. Pricing discipline should allow them to recover most of the increased costs, barring any major economic disruptions. Maersk's strategy also includes use of scrubbers and fuel blending. Hapag-Lloyd are installing scrubbers too, as well as trialling the use of liquified natural gas (LNG).

Both are likely to see an uptick in their debt ratios should they not be able to pass on the increased costs. As of the end of September, Maersk’s and Hapag-Lloyd’s net leverage ratios stood at a reasonable 2.5x and 3.5x, respectively6. In addition, both have healthy debt maturity profiles with no major upcoming maturities.

Other players may be less well positioned. CMA CGM’s net leverage ratio was 5.9x at end-September 2019 and the company has >$1bn worth of debt maturing in 2020-217. Consequently, CMA CGM has announced asset sales to increase liquidity. Any sign of poor pass-through of fuel costs or deterioration in the wider market is likely to weaken the prices on CMA’s bonds which, as seen in figure two, have been volatile.