Legislative and regulatory 2026 Global Policy Outlook

Our team covers each region’s political contests, fiscal initiatives, and regulations, and examines how these issues may impact the financial landscape.

Navigate the ever-changing regulatory environment with insights from our global team of legislative experts.

Our team covers each region’s political contests, fiscal initiatives, and regulations, and examines how these issues may impact the financial landscape.

As Chief Justice John Roberts starts his 20th year in the court, the conservative 6-3 majority SCOTUS will make decisions with profound generational implications.

How long will the government shutdown last, what off-ramps are available to reopen the government, and are permanent cuts to federal jobs in the cards?

Our team’s latest newsletter explores the potential impacts of crypto regulations, tariffs, and “One Big Beautiful Bill.“

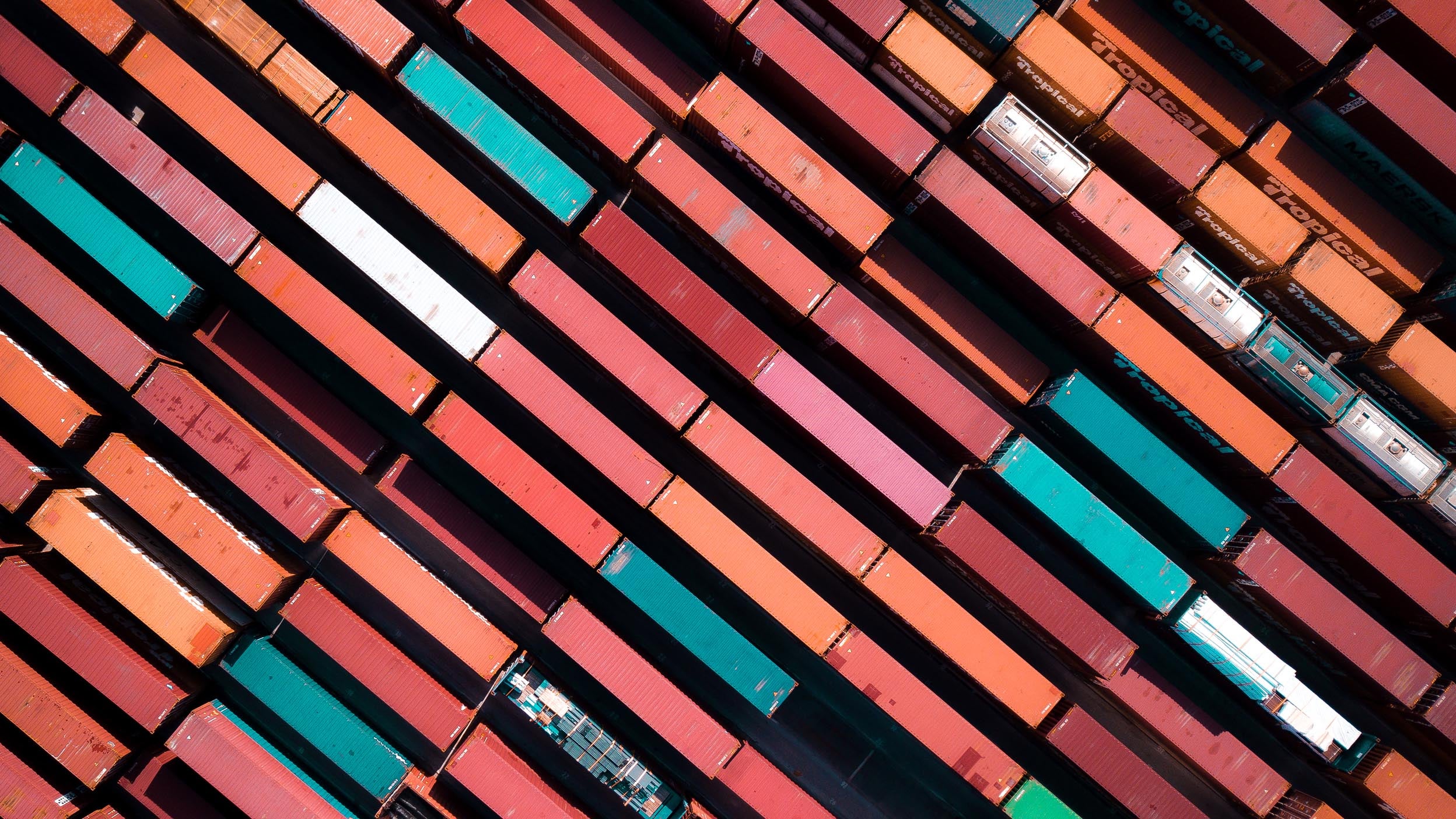

We highlight policy issues to watch in the second half in the US, UK, Europe, and Asia Pacific, including trade and tariffs.

Deregulation and tax cuts could potentially provide a boost to US economic and market growth, while tariffs and immigration restrictions could pose challenges.

Fresh perspectives on economic trends and events impacting the global markets.

Insights on investing implications, market movements, and structural changes in a shifting world.

Proprietary research and insightful analysis on key themes driving global markets and industries.

Help your participants get more out of retirement through our innovative thinking and in-depth, proprietary research.

Explore our latest insights on investment opportunities and potential ways to use ETFs in a portfolio.

Insights on the economy, the markets, and investments from Invesco’s team of experts.

NA1932809

This link takes you to a site not affiliated with Invesco. The site is for informational purposes only. Invesco does not guarantee nor take any responsibility for any of the content.