Return to state-led industrial policy in the US heralds the new tech race

US-China rivalry has recently been centered on a new “tech-race” that could usher in an era of innovative technologies that can benefit consumers.

The United States Senate just passed a USD 280bn industrial policy spending bill to bolster American technological prowess in what is fast-becoming a tech-race with China.1 Long a critic of Chinese government’s subsidies to key industries, US policymakers, in an about-face, are now quickly embracing government intervention in industrial policy in order to “win the 21st century.”

The policy calls for diverting federal money into developing innovative technologies. At the core of this plan lies USD 52bn in subsidies and tax credits to US semiconductor manufacturers.

The global chip shortage during the pandemic severely disrupted the US industrial sector, almost all of which depends on a steady supply of chips and brought to light the country’s near-total reliance on Chinese supply chains and foreign-made semiconductor chips.

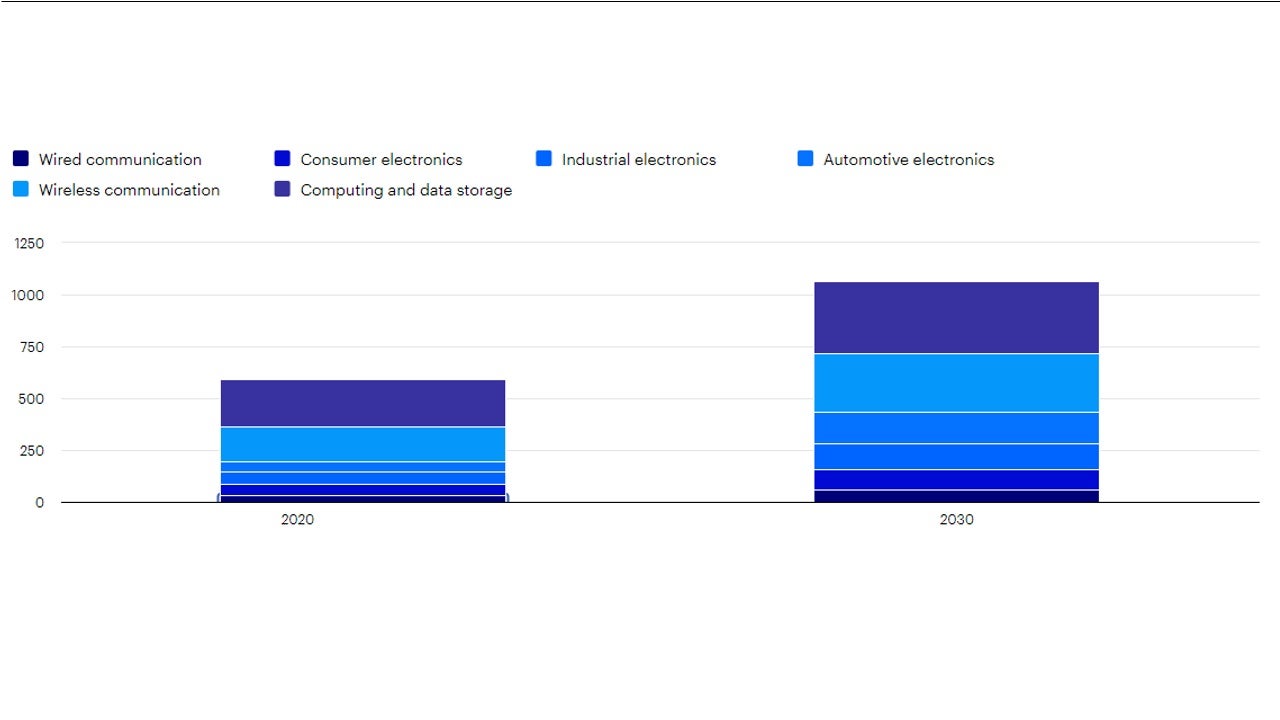

The recent global semiconductor shortage has also highlighted key vulnerabilities of reliance on a few large offshore foundries for global chip manufacturing. After all, semiconductors underpin both economic and national security concerns as a vital component in any advanced technology, including military equipment ranging from radars to fighter jets. Semiconductors can be seen as the key technological commodity of the 21st Century (Figure 1).

Source: McKinsey & Company. Data as of 2021.

Since the end of the Cold War, though, the imperative for government-led industrial policy in the US has waned, leading to underinvestment in semiconductors production and leaving other nations with lower labor costs room to build massive economies of scale. As such, while the US created the semiconductor industry, over 80% of foundries (called “fabs” in industry parlance) by revenue currently sit in Asia.2

China made their own policy pivot towards progress in innovation and technology in 2017, when President Xi called for China to “become a global leader in innovation.” Last year, China’s 5-year plan and plenum declared that “self-reliance in science and technology is a strategic pillar of national development.” Recent sanctions placed on some of China’s preeminent technology companies highlight the country’s reliance on US technology and policymakers’ urgency to reduce vulnerabilities.

Chinese authorities are putting their money where their mouth is: in 2020, the State Council announced that corporate taxes for advanced fabs would be eliminated for 10 years, and that the government would also offer insurance to fabs for their suppliers.3 Chinese semiconductor companies have also raised billions in capital over the past few years and now trade at steep premium valuations relative to their long-established Taiwanese peers.

While it’s hard to see Chinese semiconductor companies leapfrogging to become industry-leaders in the immediate future, there’s a good chance that they can become recognizable global players in certain industry segments over the next decade.

It is important to stress that there are two basic types of semiconductor chips: ‘leading edge’ digital chips used for more sophisticated applications such as computers and cell phones and ‘trailing edge’ or ‘mature’ analog chips used for less demanding applications such as automobiles and washing machines.

Currently, 90% of the most advanced ‘leading edge’ chips, known as the 5nm, are produced by a single Taiwanese manufacturer.4 Meanwhile, US and Chinese foundries make none. Taiwan continues to pioneer the latest technology in chipmaking with plans to put an even more advanced chip, the 3nm, into volume production later this year, with a ramp-up in capital expenditures further supporting industry development.5

Wrestling away Taiwanese chip manufacturing dominance will not come easy. It takes over two years to start a fabrication plant. Building up the intellectual capital and industrial capacity will take significantly more investment and time. When a leading Taiwan manufacturer set up their first US plant over 25 years ago, they quickly realized how far US manufacturing expertise had eroded after decades of offshoring. Even with this latest injection of government support, reversing this powerful trend will be challenging.

But taking on Taiwan in the “leading edge” chips race is perhaps not even necessary. Expanding demand for mature analog chips is an opportunity for Chinese fabs to focus their efforts on building massive scale in this market segment. Indeed, while China’s largest chip manufacturer has apparently succeeded in building their own 7nm chip, record-high revenues from 2021 were nonetheless driven by demand for mature nodes.6 We foresee continued high demand for such mature technologies, for example in chip-heavy electric vehicle production.

As the US returns to an era of government-led support for industrial advancement, healthy global competition is likely to create winners across market segments, diversifying production and leaving the industry much less concentrated than it is today. With more fabs able to produce a wider range of both leading and mature chips, consumers can look forward to both increasingly powerful and efficient phones and PCs, without having to wait months for a new car.

Modern industrial strategies are complex, requiring extensive state involvement with supporting research and development, subsidies, and infrastructure programs as part of a carefully structured long-term plan. The geopolitical chip war is shaping up to be one worth watching closely.

A version of this article appeared in South China Morning Post on 4th August 2022.

Investment risks

The value of investments and any income will fluctuate (this may partly be the result of exchange rate fluctuations) and investors may not get back the full amount invested.

When investing in less developed countries, you should be prepared to accept significantly large fluctuations in value.

Investment in certain securities listed in China can involve significant regulatory constraints that may affect liquidity and/or investment performance.

当資料ご利用上のご注意

当資料は情報提供を目的として、インベスコ・アセット・マネジメント株式会社(以下、「当社」)のグループに属する運用プロフェッショナルが英文で作成したものであり、法令に基づく開示書類でも金融商品取引契約の締結の勧誘資料でもありません。内容には正確を期していますが、必ずしも完全性を当社が保証するものではありません。また、当資料は信頼できる情報に基づいて作成されたものですが、その情報の確実性あるいは完結性を表明するものではありません。当資料に記載されている内容は既に変更されている場合があり、また、予告なく変更される場合があります。当資料には将来の市場の見通し等に関する記述が含まれている場合がありますが、それらは資料作成時における作成者の見解であり、将来の動向や成果を保証するものではありません。また、当資料に示す見解は、インベスコの他の運用チームの見解と異なる場合があります。過去のパフォーマンスや動向は将来の収益や成果を保証するものではありません。当社の事前の承認なく、当資料の一部または全部を使用、複製、転用、配布等することを禁じます。

IM2022-062

そのほかの投資関連情報はこちらをご覧ください。https://www.invesco.com/jp/ja/institutional/insights.html