Is China entering a demographic crisis?

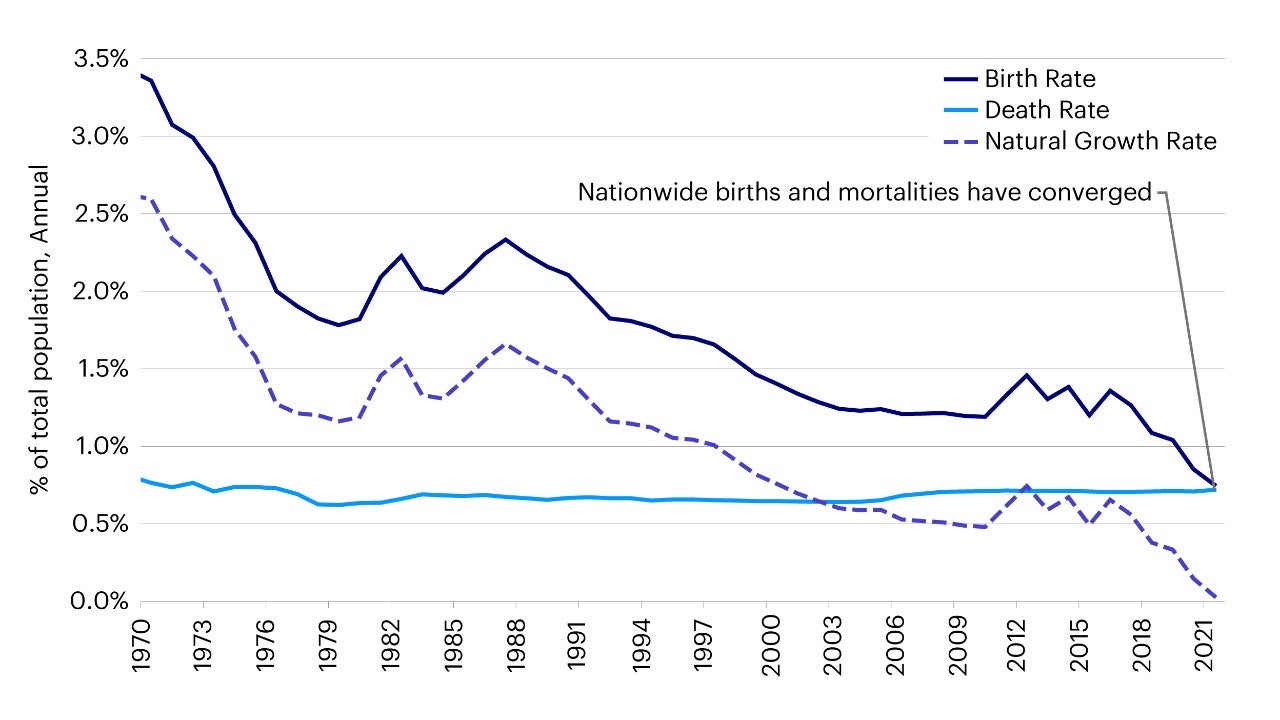

China’s National Bureau of Statistics recently published census data that showed the country’s population growth is slowing and aging sooner than anticipated. The overall population in 2021 increased by only 0.03% from the prior year – the slowest growth in 60 years since the Great Leap Forward in 1959-1961.1 If births continue to decline this year, as many observers expect, it’s possible that China’s population has already peaked and that a contraction could start as early as this year (Figure 1).

Source: China National Bureau of Statistics (NBS). Data as of 2021.

This is much earlier than the official government estimate of 2030 and a striking demographic trend that raises longer-term economic and policy questions.2

The most remarkable datapoint was the drop in total births which fell by -11.5% last year, although we should remember this is an improvement from the -18% decrease in 2020. There is evidence that the pandemic has negatively impacted births – note that in Hubei, which was the epicentre of COVID-19 beginning in 2000, births declined by -27.0% in 2020 vs. -1.6% in the prior year.3

There are examples in other countries, notably the US and certain EU countries that saw births rebound after the initial pandemic uncertainties started to wane, which implies these households chose to delay having births. It’s certainly possible that China experiences this rebound in the future, but this is unlikely in 2022 due to weaker economic growth and continued restrictions on movement to control the pandemic.

But the COVID pandemic is not the key driver of China’s declining population. The number of new marriages and population of women at peak child-bearing age has been declining for years. Families cite a number of deep-rooted socioeconomic issues that influence their decision to delay marriage or having children, including the high costs of living and childrearing, onerous work hours and obligations of elderly care. A 2021 survey indicated that Chinese women were willing to have just 1.8 children on average, below the 2.1 replacement level needed for a stable population.4

This demographic challenge is not just a problem in China. Birth rates across the globe were falling even before the pandemic, including in developing markets – even India, which has GDP per capita of about 1/5 that of China’s, reported in 2021 that the country’s birth rate had fallen below the replacement ration of 2.1 births per woman for the first time on record.

The Chinese government is taking action at all levels of administration, with “common prosperity” principles driving reforms to address childcare costs. Typical maternity leave in 20 provinces has been extended, for-profit education services are facing new restrictions and a rotation program to bring teachers from top school districts to less well-off ones has launched.

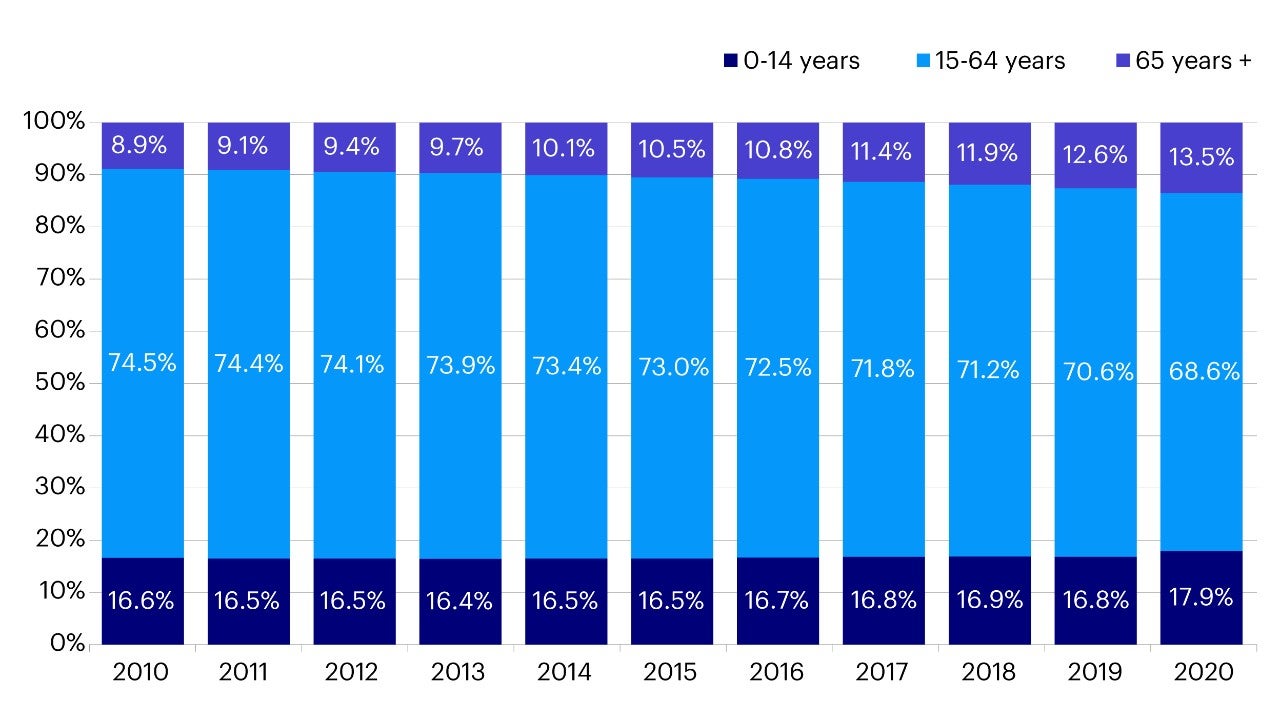

The rapid decline in births is intensifying the other major demographic challenge facing China – a rapidly aging population. The working age population (aged 15-64) decreased by -2.69% between 2019 and 2020, driving the old age dependency ratio from 11% in 2010 to 20% in 2020. UN estimates suggest that China’s population aged 65 or above would make up 25% of China’s total population as early as 2050 (Figure 2).5

Source: China National Bureau of Statistics (NBS). Data as of 2021.

Policymakers have already confirmed that they plan to incrementally raise the mandatory retirement age (currently 60 for men and 55 for women) which could help to buffer a shrinking labour force. Other initiatives such as the development of the 3rd pillar of China’s pensions system and elevating labour productivity by increasing R&D will play an important role in ensuring China adapts to the ageing population.

In some ways, the challenging circumstances that China finds itself in today reflect the dramatic rise in living standards that the country has experienced in just two generations. The key question now is: how much impact can policy make on driving birth rates?

In this regard, there are few encouraging precedents. While many countries have instituted “pro-natalist” policies since the middle of the 20th century, few have been effective in driving sustained population growth. The stark reality is that China is likely to continue experiencing a birth rate that is below for replacement ratio for the foreseeable future.

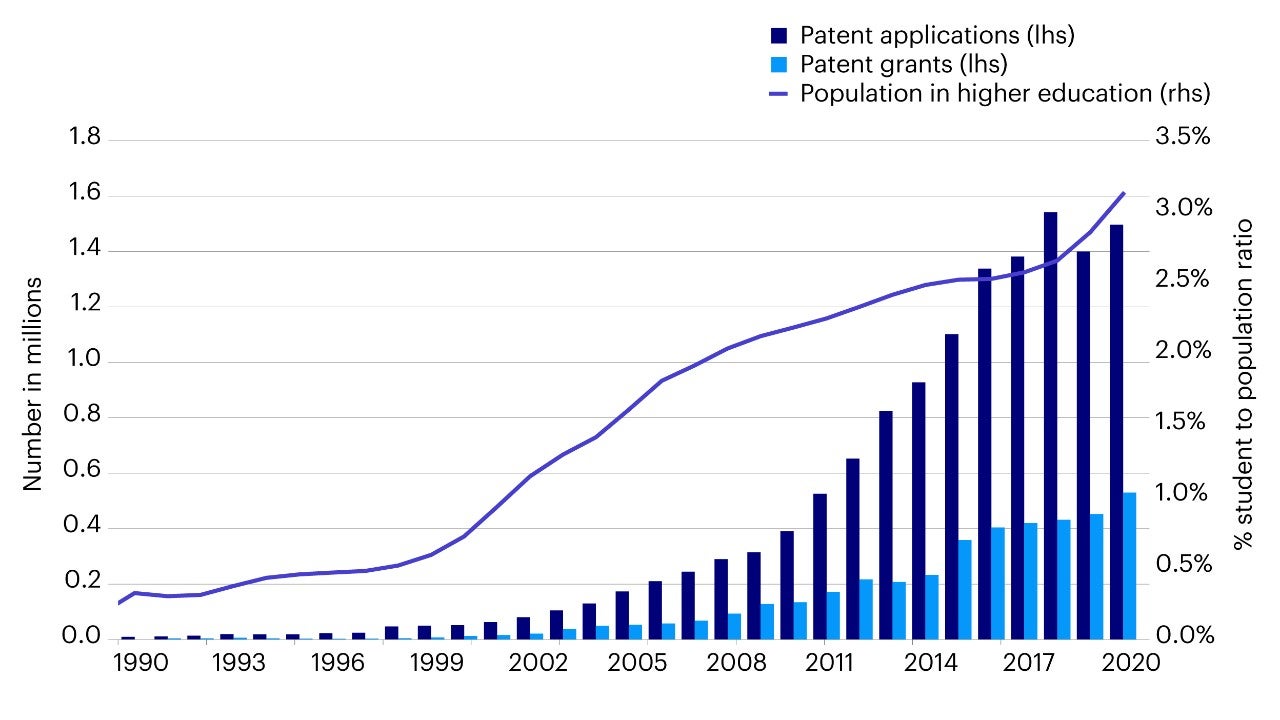

The combined burden of plateauing population growth coupled with a greying society seemingly presents a hurdle for an economy that has relied on its youthful population to propel its economy forward through urbanization and to becoming an industrial powerhouse. Policymakers are already transitioning the economy to one that is more services and knowledge-based intensive. The younger generation in China is vastly more educated than the one before it, and human capital development has been heavily invested in with the university student to population ratio surpassing 3%.6 Patent applications, a metric for innovation, shows that 1.5 million applications were filed in 2020 (Figure 3).7

Source: World Intellectual Property Organization, China Nation Bureau of Statistics (NBS). Data as of 2020.

Rather than seeing slowing demographics and an ageing population as only a challenge to China’s development, we should also see it as an opportunity. The key priority for the country must now turn to productivity growth, rather than topline aggregate growth in the labour force. High growth and technology companies are already leading the way towards a more productive digitized economy.

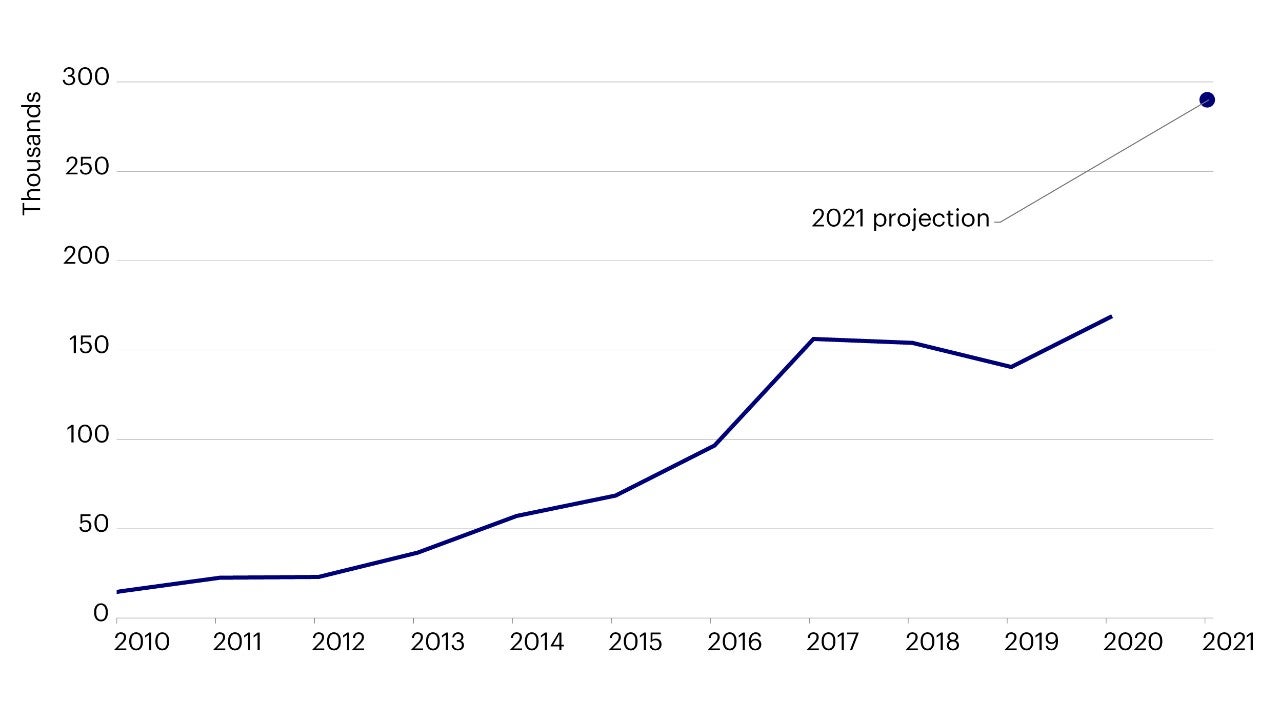

Technological developments across the economy will be key to driving productivity gains. The country is at the forefront of cutting-edge capabilities in robotics. 168,377 Chinese industrial robots were installed in 2020 and projections for 2021 estimate it at around 290,000 (Figure 4).8 China also leads the way in artificial intelligence (AI), representing 28% of the world’s AI research production.9

Source: International Federation of Robotics. Data as of 2021.

Meanwhile, despite the population plateau, China’s consumer market continues to grow and mature. The vast “silver” generation creates new opportunities for goods and services catering to an ageing population. It’s likely that spending and investments on assisted living and health care should rise with an ageing population, benefiting pharmaceuticals, providers of medical devices, and internet health care companies.

As we look to a post-pandemic future, all signs points to a new paradigm where essentially all of the world’s major economies experience lower population growth. This reality will require a different growth model that prioritizes productivity gains and enhancements in the standard of living across society. Policymakers in China and beyond will need to think creatively about how they can prepare their economies for such a future.

A version of this article appeared in South China Morning Post on 5th February 2022.

Investment risks

The value of investments and any income will fluctuate (this may partly be the result of exchange rate fluctuations) and investors may not get back the full amount invested.

When investing in less developed countries, you should be prepared to accept significantly large fluctuations in value.

Investment in certain securities listed in China can involve significant regulatory constraints that may affect liquidity and/or investment performance.

当資料ご利用上のご注意

当資料は情報提供を目的として、インベスコ・アセット・マネジメント株式会社(以下、「当社」)のグループに属する運用プロフェッショナルが英文で作成したものであり、法令に基づく開示書類でも金融商品取引契約の締結の勧誘資料でもありません。内容には正確を期していますが、必ずしも完全性を当社が保証するものではありません。また、当資料は信頼できる情報に基づいて作成されたものですが、その情報の確実性あるいは完結性を表明するものではありません。当資料に記載されている内容は既に変更されている場合があり、また、予告なく変更される場合があります。当資料には将来の市場の見通し等に関する記述が含まれている場合がありますが、それらは資料作成時における作成者の見解であり、将来の動向や成果を保証するものではありません。また、当資料に示す見解は、インベスコの他の運用チームの見解と異なる場合があります。過去のパフォーマンスや動向は将来の収益や成果を保証するものではありません。当社の事前の承認なく、当資料の一部または全部を使用、複製、転用、配布等することを禁じます。

IM2021-103

そのほかの投資関連情報はこちらをご覧ください。https://www.invesco.com/jp/ja/institutional/insights.html